Journal of Researches

The Voyage of the Beagle

Charles Darwin

Information about text on this page  | |

|---|---|

Illustrations in selected editions  | |

| TABLE OF CONTENTS | |

| 1890 | Prefatory Notice |

| Duke of Argyll's Preface | |

| Darwin's Original Preface | |

| 1905 | Concerning the “Beagle” |

| Charles Darwin | |

| I | ST. JAGO—CAPE DE VERD ISLANDS |

| II | RIO DE JANEIRO |

| III | MALDONADO |

| IV | RIO NEGRO TO BAHIA BLANCA |

| V | BAHIA BLANCA |

| VI | BAHIA BLANCA TO BUENOS AYRES |

| VII | BUENOS AYRES TO ST. FE |

| VIII | BANDA ORIENTAL AND PATAGONIA |

| IX | SANTA CRUZ, PATAGONIA, FALKLANDS |

| X | TIERRA DEL FUEGO |

| XI | STRAIT OF MAGELLAN—COAST CLIMATES |

| XII | CENTRAL CHILE |

| XIII | CHILOE AND CHONOS ISLANDS |

| XIV | CHILOE AND CONCEPCION: EARTHQUAKE |

| XV | PASSAGE OF THE CORDILLERA |

| XVI | NORTHERN CHILE AND PERU |

| XVII | GALAPAGOS ARCHIPELAGO |

| XVIII | TAHITI AND NEW ZEALAND |

| XIX | AUSTRALIA |

| XX | KEELING ISLAND—CORAL FORMATIONS |

| XXI | MAURITIUS TO ENGLAND |

| Show King et al Proceedings … (vol. 1) | |

| Show FitzRoy's Proceedings … (vol. 2) | |

| Show Darwin's Journal & Remarks (vol. 3) | |

HMS Beagle track, England to Strait of Magellan  | |

PREFATORY NOTICE TO THE ILLUSTRATED EDITION.

This work was described, on its first appearance, by a writer in the Quarterly Review§ as “One of the most interesting narratives of voyaging that it has fallen to our lot to take up, and one which must always occupy a distinguished place in the history of scientific navigation.”

§ Quarterly Review, Vol. LXV, No. CXXIX, March 1840, pp. 194-234. Publisher Henry Colburn used the same quotation 50 years earlier to describe the 1839 King and FitzRoy Narratives. The unsigned review was in fact for all three volumes; that is, for King, FitzRoy and Darwin. See the “Notes” entry at the bottom of the complete review for a few more details.

This prophecy has been amply verified by experience; the extraordinary minuteness and accuracy of Mr. Darwin's observations, combined with the charm and simplicity of his descriptions, have ensured the popularity of this book with all classes of readers—and that popularity has even increased in recent years. No attempt, however, has hitherto been made to produce an illustrated edition of this valuable work: numberless places and objects are mentioned and described, but the difficulty of obtaining authentic and original representations of them drawn for the purpose has never been overcome until now.

Most of the views given in this work are from sketches made on the spot by Mr. Pritchett, with Mr. Darwin's book by his side. Some few of the others are taken from engravings which Mr. Darwin had himself selected for their interest as illustrating his voyage, and which have been kindly lent by his son.

Mr. Pritchett's name is well known in connection with the voyages of the Sunbeam and Wanderer, and it is believed that the illustrations, which have been chosen and verified with the utmost care and pains, will greatly add to the value and interest of the “Voyage of a Naturalist.”

JOHN MURRAY.

Dec. 1889.§

§ The above Notice appears only in the Murray 1890 Illustrated Edition.

The Duke of Argyll, in

“The Nineteenth Century,” September 1887.

“The most delightful of all Mr. Darwin's works is the first he ever wrote. It is his Journal as the Naturalist of H.M.S. Beagle in her exploring voyage round the world from the beginning of 1832 to nearly the end of 1836. It was published in 1842 {sic, 1839} and a later edition appeared in 1845. Celebrated as this book once was, few probably read it now. Yet in many respects it exhibits Darwin at his best, and if we are ever inclined to rest our opinions upon authority, and to accept without doubt what a remarkable man has taught, I do not know any work better calculated to inspire confidence than Darwin's Journal. It records the observations of a mind singularly candid and unprejudiced—fixing upon nature a gaze keen, penetrating, and curious, but yet cautious, reflective, and almost reverent. The thought of how little we know, of how much there is to be known, and of how hardly we can learn it, is the thought which inspires the narrative as with an abiding presence. There is, too, an intense love of nature and an intense admiration of it, the expression of which is carefully restrained and measured, but which seems often to overflow the limits which are self-imposed. And when Man, the highest work of nature, but not always its happiest or its best, comes across his path, Darwin's observations are always noble. ‘A kindly man moving among his kind’ seems to express his spirit. He appreciates every high calling, every good work, however far removed it may be from that to which he was himself devoted. His language about the missionaries of Christianity is a signal example, in striking contrast with the too common language of lesser men. His indignant denunciation of slavery presents the same high characteristics of a mind eminently gentle and humane. In following him we feel that not merely the intellectual but the moral atmosphere in which we move is high and pure. And then, besides these great recommendations, there is another which must not be overlooked,—We have Darwin here before he was a Darwinian.”§

§ The above is an excerpt by the Duke of Argyll, which appears only in the 1890 edition of Darwin's Journal published by Thomas Nelson and Sons. It concludes with “FROM THE ORIGINAL PREFACE” and is immediately followed by Darwin's own “Preface.” See Comparison of Selected Editions for more details about the Nelson edition.

FROM THE ORIGINAL PREFACE.

I have stated in the preface to the first Edition of this work, and in the “Zoology of the Voyage of the Beagle,” that it was in consequence of a wish expressed by Captain Fitz Roy,§ of having some scientific person on board, accompanied by an offer from him of giving up part of his own accommodations, that I volunteered my services, which received, through the kindness of the hydrographer, Captain Beaufort, the sanction of the Lords of the Admiralty. As I feel that the opportunities which I enjoyed of studying the Natural History of the different countries we visited, have been wholly due to Captain Fitz Roy, I hope I may here be permitted to repeat my expression of gratitude to him; and to add that, during the five years we were together, I received from him the most cordial friendship and steady assistance. Both to Captain Fitz Roy and to all the Officers of the Beagle * I shall ever feel most thankful for the undeviating kindness with which I was treated during our long voyage.

§ FitzRoy mentions this in the Narrative …, vol. I, and again—this time mentioning Darwin—in Narrative …, vol. II

* I must take this opportunity of returning my sincere thanks to Mr. Bynoe, the surgeon of the Beagle, for his very kind attention to me when I was ill at Valparaiso.

This volume contains, in the form of a Journal, a history of our voyage, and a sketch of those observations in Natural History and Geology, which I think will possess some interest for the general reader. I have in this edition largely condensed and corrected some parts, and have added a little to others, in order to render the volume more fitted for popular reading; but I trust that naturalists will remember, that they must refer for details to the larger publications which comprise the scientific results of the Expedition. The Zoology of the Voyage of the Beagle includes an account of the Fossil Mammalia, by Professor Owen; of the Living Mammalia, by Mr. Waterhouse; of the Birds, by Mr. Gould; of the Fish, by the Rev. L. Jenyns; and of the Reptiles, by Mr. Bell. I have appended to the descriptions of each species an account of its habits and range. These works, which I owe to the high talents and disinterested zeal of the above distinguished authors, could not have been undertaken, had it not been for the liberality of the Lords Commissioners of Her Majesty's Treasury, who, through the representation of the Right Honourable the Chancellor of the Exchequer, have been pleased to grant a sum of one thousand pounds towards defraying part of the expenses of publication.

| 1890 Nelson & Sons edition | 1890 Murray Illustrated Edition |

|---|---|

|

I have myself published separate volumes on the ‘Structure and Distribution of Coral Reefs;’ on the ‘Volcanic Islands visited during the Voyage of the Beagle;’ and on the ‘Geology of South America.’ The sixth volume of the ‘Geological Transactions’ contains two papers of mine on the Erratic Boulders and Volcanic Phenomena of South America. Messrs. Waterhouse, Walker, Newman, and White, have published several able papers on the Insects which were collected, and I trust that many others will hereafter follow. The plants from the southern parts of America will be given by Dr. J. Hooker, in his great work on the Botany of the Southern Hemisphere. The Flora of the Galapagos Archipelago is the subject of a separate memoir by him, in the ‘Linnean Transactions.’ The Reverend Professor Henslow has published a list of the plants collected by me at the Keeling Islands; and the Reverend J. M. Berkeley has described my cryptogamic plants. | |

|

I must be here allowed to return my most sincere thanks to the Reverend Professor Henslow, who, when I was an under-graduate at Cambridge, was one chief means of giving me a taste for natural history; who, during my absence, took charge of the collections I sent home, and by his correspondence directed my endeavors; and who, since me return, has constantly rendered me every assistance which the kindest friend could offer. |

I shall have the pleasure of acknowledging the great assistance which I have received from several other naturalists, in the course of this and my other works; but I must be here allowed to return my most sincere thanks to the Reverend Professor Henslow, who, when I was an undergraduate at Cambridge, was one chief means of giving me a taste for Natural History,—who, during my absence, took charge of the collections I sent home, and by his correspondence directed my endeavours,—and who, since my return, has constantly rendered me every assistance which the kindest friend could offer. June, 1845 |

Concerning the “Beagle”

Charles Darwin's voyage round the world as naturalist to the Beagle was, he said, “by far the most important event in my life, and has determined my whole career.”

It was also a most momentous incident in its effect on modern thought. “Yet,” says Darwin, “it depended on so small a circumstance as my uncle {Josiah Wedgwood II} offering to drive me thirty miles to Shrewsbury and on such a trifle as the shape of my nose.”§

§ In his Autobiography, Darwin mentions that FitzRoy “… doubted whether any one with my nose could possess sufficient energy and determination for the voyage.”

The voyage brought to Darwin's knowledge certain facts which “seemed to throw some light on the origin of species—that mystery of mysteries.” Darwin's great theory of Natural Selection resulted from this voyage, and that theory, as Grant Allen puts it, “completely revolutionized the sciences of Botany and Zoology, and made the doctrine of Organic Evolution, till then admitted only by a few advanced philosophical biologists, the universal creed of all men of science.”

Huxley declares that the “emergence of the philosophy of evolution in the attitude of claimant to the throne of the world of thought, from the limbo of hatred and, as many hoped, forgotten things, is the most portentious event in the nineteenth century.”

The Beagle, commanded by Captain FitzRoy, was of 235 tons, “rigged as a barque and carrying six guns.” Long after Darwin's voyage it was used by the Japanese as a training ship in Yokosuka (1888).§

§ This little bit of mis-information may be traced to The Fate of the Beagle in the May, 1900 issue of Popular Science Monthly.

Darwin's cabin, shared with an officer, was very small. “Captain FitzRoy says he will take care that one corner is so fitted up that I shall be comfortable in it, and shall consider it my home, but that also I shall have the use of his. My cabin is the drawing one; and in the middle is a large table, on which we two sleep in hammocks.”

“My father used to say,” writes F. Darwin in his father's “Life,” “that it was the absolute necessity of tidiness in the cramped space on the Beagle that helped ‘to give him his methodical habits of working.’ On the Beagle too, he would say that he learned what he considered the golden rule for saving time: i.e., taking care of the minutes.”

When the voyage was over, he told Captain FitzRoy that he would not exchange his recollections and what he had learned on Natural History for twice ten thousand a year.

Charles Darwin (one-page biography)

Charles Robert Darwin, grandson of Erasmus Darwin, physician, poet and naturalist, and of Josiah Wedgwood, the celebrated potter, was born at Shrewsbury, February 12, 1809.

From Shrewsbury Grammar School he was sent (1825) as a medical student to Edinburgh University, but disliking medicine as a profession, he reluctantly acquiesced in his father's suggestion that he should enter the church; went to Christ's College, Cambridge, but instead of preparing for the church, gave himself up to botany and geology, and accepted an invitation to go as naturalist to H.M.S. Beagle on a voyage round the world; started December 27, 1831, and was away five years. Returning home, he published in succession his Journal, the Zoology of the Beagle, his theory of Coral Reefs, and Geological Observations on Volcanic Islands.

In 1839 Darwin married his cousin, Emma Wedgwood, and went to live at Down, in Kent. Here he laboriously elaborated the germ ideas which resulted from his Voyage, and in 1859 was published {On} The Origin of Species by Means of Natural Selection, which Darwin regarded as the chief work of his life. Its effect was enormous, for till this time scientific men did not doubt the permanence of species.

Then followed the Fertilization of Orchids (1862), Variations of Plants and Animals under Domestication (1867). As soon as Darwin became convinced that species were mutable productions, he saw that man must come under the same law. The Descent of Man (1871) was the result, and soon upraised “a storm of mingled wrath, wonder and admiration.”§

§ Edinburgh Review, July, 1871, vol. CXXXIV (134), no. CCLXXIII (273), p. 100.

Darwin's life had little interest apart from his work, but it was one of amazing industry. One experiment in connection with his book on the Formation of Vegetable Mould through the Action of Worms extended over thirty years. He was always actuated by a passion for truth. His methods of studying nature were finely conscientious and ingenious.

Darwin lived till he was 73, and was at work examining a plant in his study the day before he died (April 18, 1882). He lies in Westminster Abbey.

CHAPTER I

ST. JAGO—CAPE DE VERD ISLANDS

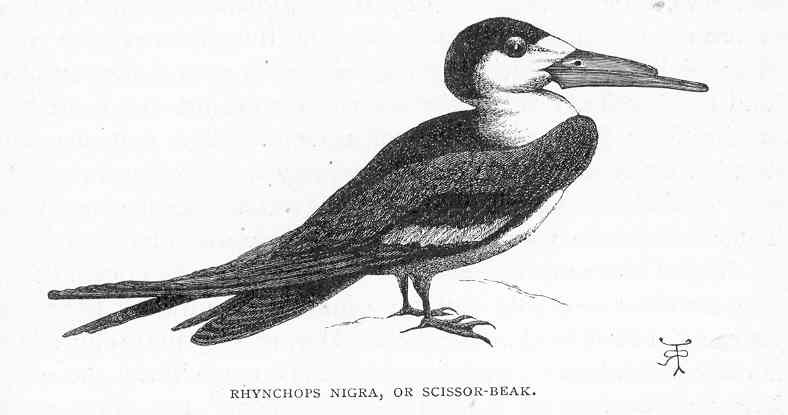

Porto Praya—Ribeira Grande—Atmospheric Dust with Infusoria—Habits of a Sea-slug and Cuttle-fish—St. Paul's Rocks, non-volcanic—Singular Incrustations—Insects the first Colonists of Islands—Fernando Noronha—Bahia—Burnished Rocks—Habits of a Diodon—Pelagic Confervae and Infusoria—Causes of discoloured Sea.

After having been twice driven back by heavy southwestern gales, Her Majesty's§ ship Beagle, a ten-gun brig, under the command of Captain Fitz Roy, R. N., sailed from Devonport  on the 27th of December, 1831. The object of the expedition was to complete the survey of Patagonia and Tierra del Fuego, commenced under Captain King in 1826 to 1830,—to survey the shores of Chile, Peru, and of some islands in the Pacific—and to carry a chain of chronometrical measurements round the World.

on the 27th of December, 1831. The object of the expedition was to complete the survey of Patagonia and Tierra del Fuego, commenced under Captain King in 1826 to 1830,—to survey the shores of Chile, Peru, and of some islands in the Pacific—and to carry a chain of chronometrical measurements round the World.

§ The voyage took place during the reign of William IV; thus Darwin sailed on His Majesty's ship Beagle.

On the 6th of January we reached Teneriffe,  but were prevented landing {at Santa Cruz}, by fears of our bringing the cholera:§ the next morning we saw the sun rise behind the rugged outline of the Grand Canary island, and suddenly illuminate the Peak of Teneriffe, whilst the lower parts were veiled in fleecy clouds. This was the first of many delightful days never to be forgotten. On the 16th of January, 1832, we anchored at Porto Praya,

but were prevented landing {at Santa Cruz}, by fears of our bringing the cholera:§ the next morning we saw the sun rise behind the rugged outline of the Grand Canary island, and suddenly illuminate the Peak of Teneriffe, whilst the lower parts were veiled in fleecy clouds. This was the first of many delightful days never to be forgotten. On the 16th of January, 1832, we anchored at Porto Praya,  in St. Jago {now, Santiago}, the chief island of the Cape de Verd archipelago.

in St. Jago {now, Santiago}, the chief island of the Cape de Verd archipelago.

§ FitzRoy notes Darwin's disappointment in his Narrative, but Darwin himself offers no further comment here. He did however express his disappointment in the 6th January, 1832 entry in his Diary:

Oh misery, misery—we were just preparing to drop our anchor within ½ a mile of Santa Cruz when a boat came alongside bringing with it our death warrant.—The consul declared we must perform a rigorous quarantine of twelve days.—Those who have never experienced it can scarcely conceive what a gloom it cast on every one: Matters were soon decided by the Captain ordering all sail to be set & make a course for the Cape Verd Islands.

| Modern names for places listed above | |

|---|---|

| Teneriffe | Tenerife (Teneriffe in Australia) |

| Porto Praya | Porto Praia |

| St. Jago | Santiago |

| Cape de Verd | Cape Verde, or Cabo Verde |

The neighbourhood of Porto Praya, viewed from the sea, wears a desolate aspect. The volcanic fires of a past age, and the scorching heat of a tropical sun, have in most places rendered the soil unfit for vegetation. The country rises in successive steps of table-land, interspersed with some truncate conical hills, and the horizon is bounded by an irregular chain of more lofty mountains. The scene, as beheld through the hazy atmosphere of this climate, is one of great interest; if, indeed, a person, fresh from sea, and who has just walked, for the first time, in a grove of cocoa-nut trees, can be a judge of anything but his own happiness. The island would generally be considered as very uninteresting, but to anyone accustomed only to an English landscape, the novel aspect of an utterly sterile land possesses a grandeur which more vegetation might spoil. A single green leaf can scarcely be discovered over wide tracts of the lava plains; yet flocks of goats, together with a few cows, contrive to exist. It rains very seldom, but during a short portion of the year heavy torrents fall, and immediately afterwards a light vegetation springs out of every crevice. This soon withers; and upon such naturally formed hay the animals live. It had not now rained for an entire year. When the island was discovered, the immediate neighbourhood of Porto Praya was clothed with trees, * the reckless destruction of which has caused here, as at St. Helena, and at some of the Canary islands, almost entire sterility. The broad, flat-bottomed valleys, many of which serve during a few days only in the season as water-courses, are clothed with thickets of leafless bushes. Few living creatures inhabit these valleys. The commonest bird is a kingfisher (Dacelo Iagoensis), which tamely sits on the branches of the castor-oil plant, and thence darts on grasshoppers and lizards. It is brightly coloured, but not so beautiful as the European species: in its flight, manners, and place of habitation, which is generally in the driest valley, there is also a wide difference.

* I state this on the authority of Dr. E. Dieffenbach, in his German translation of the first edition of this Journal.

One day, two of the officers and myself rode to Ribeira Grande,§ a village a few miles eastward {sic, westward} of Porto Praya. Until we reached the valley of St. Martin, the country presented its usual dull brown appearance; but here, a very small rill of water produces a most refreshing margin of luxuriant vegetation. In the course of an hour we arrived at Ribeira Grande, and were surprised at the sight of a large ruined fort§§ and cathedral. This little town, before its harbour was filled up, was the principal place in the island: it now presents a melancholy, but very picturesque appearance. Having procured a black Padre for a guide, and a Spaniard who had served in the Peninsular war as an interpreter, we visited a collection of buildings, of which an ancient church formed the principal part. It is here the governors and captain-generals of the islands have been buried. Some of the tombstones recorded dates of the sixteenth century.*

§ Today, a village named Ribeira Grande is on Ilha Santo Antao, the northernmost of the Cape Verde group. Darwin landed on Ilha Santiago, about 185 miles southeast of this island. To help keep things confusing, the village he refers to as Ribeira Grande is probably the modern Cidade Velha,  located within the administrative district now known as Ribeira Grande de Santiago, not to—but no doubt will—be confused with the above-mentioned village.

located within the administrative district now known as Ribeira Grande de Santiago, not to—but no doubt will—be confused with the above-mentioned village.

§§ Probably Forte Real de São Felipe, just east of Cidade Velha.

just east of Cidade Velha.

* The Cape de Verd Islands were discovered in 1449. There was a tombstone of a bishop with the date of 1571; and a crest of a hand and dagger, dated 1497.

The heraldic ornaments were the only things in this retired place that reminded us of Europe. The church or chapel formed one side of a quadrangle, in the middle of which a large clump of bananas were growing. On another side was a hospital, containing about a dozen miserable-looking inmates.

We returned to the Vênda † to eat our dinners. A considerable number of men, women, and children, all as black as jet, collected to watch us. Our companions were extremely merry; and everything we said or did was followed by their hearty laughter. Before leaving the town we visited the cathedral. It does not appear so rich as the smaller church, but boasts of a little organ, which sent forth singularly inharmonious cries. We presented the black priest with a few shillings, and the Spaniard, patting him on the head, said, with much candour, he thought his colour made no great difference. We then returned, as fast as the ponies would go, to Porto Praya.

† The Portuguese name for an inn. {This footnote, plus Vênda in italics, in 1890 Nelson edition only.}

Another day we rode to the village of St. Domingo, {São Domingos}  situated near the centre of the island. On a small plain which we crossed, a few stunted acacias were growing; their tops had been bent by the steady trade-wind, in a singular manner—some of them even at right angles to their trunks. The direction of the branches was exactly N. E. by N., and S. W. by S., and these natural vanes must indicate the prevailing direction of the force of the trade-wind. The travelling had made so little impression on the barren soil, that we here missed our track, and took that to Fuentes.§ This we did not find out till we arrived there; and we were afterwards glad of our mistake. Fuentes is a pretty village, with a small stream; and everything appeared to prosper well, excepting, indeed, that which ought to do so most—its inhabitants. The black children, completely naked, and looking very wretched, were carrying bundles of firewood half as big as their own bodies.

situated near the centre of the island. On a small plain which we crossed, a few stunted acacias were growing; their tops had been bent by the steady trade-wind, in a singular manner—some of them even at right angles to their trunks. The direction of the branches was exactly N. E. by N., and S. W. by S., and these natural vanes must indicate the prevailing direction of the force of the trade-wind. The travelling had made so little impression on the barren soil, that we here missed our track, and took that to Fuentes.§ This we did not find out till we arrived there; and we were afterwards glad of our mistake. Fuentes is a pretty village, with a small stream; and everything appeared to prosper well, excepting, indeed, that which ought to do so most—its inhabitants. The black children, completely naked, and looking very wretched, were carrying bundles of firewood half as big as their own bodies.

§ Fuentes = fountains in English. Location unknown.

Near Fuentes we saw a large flock of guinea-fowl—probably fifty or sixty in number. They were extremely wary, and could not be approached. They avoided us, like partridges on a rainy day in September, running with their heads cocked up; and if pursued, they readily took to the wing.

The scenery of St. Domingo possesses a beauty totally unexpected, from the prevalent gloomy character of the rest of the island. The village is situated at the bottom of a valley, bounded by lofty and jagged walls of stratified lava. The black rocks afford a most striking contrast with the bright green vegetation, which follows the banks of a little stream of clear water. It happened to be a grand feast-day, and the village was full of people. On our return we overtook a party of about twenty young black girls, dressed in excellent taste; their black skins and snow-white linen being set off by coloured turbans and large shawls. As soon as we approached near, they suddenly all turned round, and covering the path with their shawls, sung with great energy a wild song, beating time with their hands upon their legs. We threw them some vintéms,§ which were received with screams of laughter, and we left them redoubling the noise of their song.

§ Small Portuguese coins.

One morning the view was singularly clear; the distant mountains being projected with the sharpest outline on a heavy bank of dark blue clouds. Judging from the appearance, and from similar cases in England, I supposed that the air was saturated with moisture. The fact, however, turned out quite the contrary. The hygrometer gave a difference of 29.6°, between the temperature of the air, and the point at which dew was precipitated. This difference was nearly double that which I had observed on the previous mornings. This unusual degree of atmospheric dryness was accompanied by continual flashes of lightning. Is it not an uncommon case, thus to find a remarkable degree of aerial transparency with such a state of weather?

Generally the atmosphere is hazy; and this is caused by the falling of impalpably fine dust, which was found to have slightly injured the astronomical instruments. The morning before we anchored at Porto Praya, I collected a little packet of this brown-coloured fine dust, which appeared to have been filtered from the wind by the gauze of the vane at the mast-head. Mr. Lyell has also given me four packets of dust which fell on a vessel a few hundred miles northward of these islands. Professor Ehrenberg * finds that this dust consists in great part of infusoria with siliceous shields, and of the siliceous tissue of plants. In five little packets which I sent him, he has ascertained no less than sixty-seven different organic forms! The infusoria, with the exception of two marine species, are all inhabitants of fresh-water. I have found no less than fifteen different accounts of dust having fallen on vessels when far out in the Atlantic. From the direction of the wind whenever it has fallen, and from its having always fallen during those months when the harmattan is known to raise clouds of dust high into the atmosphere, we may feel sure that it all comes from Africa. It is, however, a very singular fact, that, although Professor Ehrenberg knows many species of infusoria peculiar to Africa, he finds none of these in the dust which I sent him. On the other hand, he finds in it two species which hitherto he knows as living only in South America. The dust falls in such quantities as to dirty everything on board, and to hurt people's eyes; vessels even have run on shore owing to the obscurity of the atmosphere. It has often fallen on ships when several hundred, and even more than a thousand miles from the coast of Africa, and at points sixteen hundred miles distant in a north and south direction. In some dust which was collected on a vessel three hundred miles from the land, I was much surprised to find particles of stone above the thousandth of an inch square, mixed with finer matter. After this fact one need not be surprised at the diffusion of the far lighter and smaller sporules of cryptogamic plants.

* I must take this opportunity of acknowledging the great kindness with which this illustrious naturalist§ has examined many of my specimens. I have sent (June, 1845) a full account of the falling of this dust to the Geological Society.§§

§ Christian Gottfried Ehrenberg (1795-1876).

§§ “An account of the Fine Dust which often falls on Vessels in the Atlantic Ocean.”

The geology of this island is the most interesting part of its natural history. On entering the harbour, a perfectly horizontal white band, in the face of the sea cliff, may be seen running for some miles along the coast, and at the height of about forty-five feet above the water. Upon examination this white stratum is found to consist of calcareous matter with numerous shells embedded, most or all of which now exist on the neighbouring coast. It rests on ancient volcanic rocks, and has been covered by a stream of basalt, which must have entered the sea when the white shelly bed was lying at the bottom. It is interesting to trace the changes produced by the heat of the overlying lava, on the friable mass, which in parts has been converted into a crystalline limestone, and in other parts into a compact spotted stone Where the lime has been caught up by the scoriaceous fragments of the lower surface of the stream, it is converted into groups of beautifully radiated fibres resembling arragonite. The beds of lava rise in successive gently-sloping plains, towards the interior, whence the deluges of melted stone have originally proceeded. Within historical times, no signs of volcanic activity have, I believe, been manifested in any part of St. Jago. Even the form of a crater can but rarely be discovered on the summits of the many red cindery hills; yet the more recent streams can be distinguished on the coast, forming lines of cliffs of less height, but stretching out in advance of those belonging to an older series: the height of the cliffs thus affording a rude measure of the age of the streams.

During our stay, I observed the habits of some marine animals. A large Aplysia is very common. This sea-slug is about five inches long; and is of a dirty yellowish colour veined with purple. On each side of the lower surface, or foot, there is a broad membrane, which appears sometimes to act as a ventilator, in causing a current of water to flow over the dorsal branchiae or lungs. It feeds on the delicate sea-weeds which grow among the stones in muddy and shallow water; and I found in its stomach several small pebbles, as in the gizzard of a bird. This slug, when disturbed, emits a very fine purplish-red fluid, which stains the water for the space of a foot around. Besides this means of defence, an acrid secretion, which is spread over its body, causes a sharp, stinging sensation, similar to that produced by the Physalia, or Portuguese man-of-war.

I was much interested, on several occasions, by watching the habits of an Octopus, or cuttle-fish. Although common in the pools of water left by the retiring tide, these animals were not easily caught. By means of their long arms and suckers, they could drag their bodies into very narrow crevices; and when thus fixed, it required great force to remove them. At other times they darted tail first, with the rapidity of an arrow, from one side of the pool to the other, at the same instant discolouring the water with a dark chestnut-brown ink. These animals also escape detection by a very extraordinary, chameleon-like power of changing their colour. They appear to vary their tints according to the nature of the ground over which they pass: when in deep water, their general shade was brownish purple, but when placed on the land, or in shallow water, this dark tint changed into one of a yellowish green. The colour, examined more carefully, was a French grey, with numerous minute spots of bright yellow: the former of these varied in intensity; the latter entirely disappeared and appeared again by turns. These changes were effected in such a manner, that clouds, varying in tint between a hyacinth red and a chestnut-brown,* were continually passing over the body. Any part, being subjected to a slight shock of galvanism, became almost black: a similar effect, but in a less degree, was produced by scratching the skin with a needle. These clouds, or blushes as they may be called, are said to be produced by the alternate expansion and contraction of minute vesicles containing variously coloured fluids.†

* So named according to Patrick Symes's nomenclature.

† See Encyclop. of Anat. and Physiol., article Cephalopoda

This cuttle-fish displayed its chameleon-like power both during the act of swimming and whilst remaining stationary at the bottom. I was much amused by the various arts to escape detection used by one individual, which seemed fully aware that I was watching it. Remaining for a time motionless, it would then stealthily advance an inch or two, like a cat after a mouse; sometimes changing its colour: it thus proceeded, till having gained a deeper part, it darted away, leaving a dusky train of ink to hide the hole into which it had crawled.

While looking for marine animals, with my head about two feet above the rocky shore, I was more than once saluted by a jet of water, accompanied by a slight grating noise. At first I could not think what it was, but afterwards I found out that it was this cuttle-fish, which, though concealed in a hole, thus often led me to its discovery. That it possesses the power of ejecting water there is no doubt, and it appeared to me that it could certainly take good aim by directing the tube or siphon on the under side of its body. From the difficulty which these animals have in carrying their heads, they cannot crawl with ease when placed on the ground. I observed that one which I kept in the cabin was slightly phosphorescent in the dark.

ST. PAUL'S ROCKS.—In crossing the Atlantic we hove-to during the morning of February 16th, close to the island{s} of St. Paul's.  This cluster of rocks is situated in 0° 58' north latitude, and 29° 15' west longitude.§ It is 540 miles distant from the coast of America, and 350 from the island of Fernando Noronha. The highest point is only fifty feet above the level of the sea, and the entire circumference is under three-quarters of a mile. This small point rises abruptly out of the depths of the ocean. Its mineralogical constitution is not simple; in some parts the rock is of a cherty, in others of a felspathic nature, including thin veins of serpentine. It is a remarkable fact, that all the many small islands, lying far from any continent, in the Pacific, Indian, and Atlantic Oceans, with the exception of the Seychelles and this little point of rock, are, I believe, composed either of coral or of erupted matter. The volcanic nature of these oceanic islands is evidently an extension of that law, and the effect of those same causes, whether chemical or mechanical, from which it results that a vast majority of the volcanoes now in action stand either near sea-coasts or as islands in the midst of the sea.

This cluster of rocks is situated in 0° 58' north latitude, and 29° 15' west longitude.§ It is 540 miles distant from the coast of America, and 350 from the island of Fernando Noronha. The highest point is only fifty feet above the level of the sea, and the entire circumference is under three-quarters of a mile. This small point rises abruptly out of the depths of the ocean. Its mineralogical constitution is not simple; in some parts the rock is of a cherty, in others of a felspathic nature, including thin veins of serpentine. It is a remarkable fact, that all the many small islands, lying far from any continent, in the Pacific, Indian, and Atlantic Oceans, with the exception of the Seychelles and this little point of rock, are, I believe, composed either of coral or of erupted matter. The volcanic nature of these oceanic islands is evidently an extension of that law, and the effect of those same causes, whether chemical or mechanical, from which it results that a vast majority of the volcanoes now in action stand either near sea-coasts or as islands in the midst of the sea.

§ Now, Arquipélago de São Pedro e São Paulo. Darwin's specific latitude seen above is re-written as “nearly one degree” in his Geological Observations … (1844). FitzRoy's coordinates are 0° 55' 30" N, 29° 22' 00" W, for a difference of slightly less than 9 miles. It's quite possible that Darwin was unaware of FitzRoy's coordinates and consulted some other source, which remains unknown. In any case, his account may have become the subsequent source for William James Joseph Spry's The Cruise of Her Majesty's Ship Challenger (1876, p. 86, para. 3).

The rocks are situated in 0° 58' north latitude, and 29° 15' west longitude. They are 540 miles from the coast of South America, and 350 from Fernando Noronha. The highest point is only about 60 {sic, Darwin states 50 feet} feet above the level of the sea.

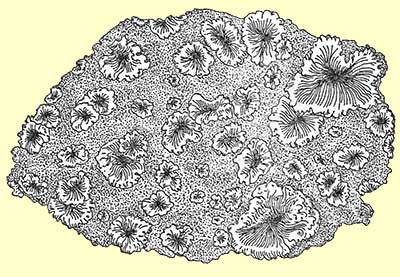

The rocks of St. Paul appear from a distance of a brilliantly white colour. This is partly owing to the dung of a vast multitude of seafowl, and partly to a coating of a hard glossy substance with a pearly lustre, which is intimately united to the surface of the rocks. This, when examined with a lens, is found to consist of numerous exceedingly thin layers, its total thickness being about the tenth of an inch. It contains much animal matter, and its origin, no doubt, is due to the action of the rain or spray on the birds' dung. Below some small masses of guano at Ascension, and on the Abrolhos Islets, I found certain stalactitic branching bodies, formed apparently in the same manner as the thin white coating on these rocks. The branching bodies so closely resembled in general appearance certain nulliporae (a family of hard calcareous sea-plants), that in lately looking hastily over my collection I did not perceive the difference. The globular extremities of the branches are of a pearly texture, like the enamel of teeth, but so hard as just to scratch plate-glass.  I may here mention, that on a part of the coast of Ascension, where there is a vast accumulation of shelly sand, an incrustation is deposited on the tidal rocks by the water of the sea, resembling{, as represented in the woodcut,} certain cryptogamic plants (Marchantiae) often seen on damp walls. The surface of the fronds is beautifully glossy; and those parts formed where fully exposed to the light are of a jet black colour, but those shaded under ledges are only grey. I have shown specimens of this incrustation to several geologists, and they all thought that they were of volcanic or igneous origin! In its hardness and translucency—in its polish, equal to that of the finest oliva-shell—in the bad smell given out, and loss of colour under the blowpipe—it shows a close similarity with living sea-shells. Moreover, in sea-shells, it is known that the parts habitually covered and shaded by the mantle of the animal, are of a paler colour than those fully exposed to the light, just as is the case with this incrustation. When we remember that lime, either as a phosphate or carbonate, enters into the composition of the hard parts, such as bones and shells, of all living animals, it is an interesting physiological fact * to find substances harder than the enamel of teeth, and coloured surfaces as well polished as those of a fresh shell, reformed through inorganic means from dead organic matter—mocking, also, in shape, some of the lower vegetable productions.

I may here mention, that on a part of the coast of Ascension, where there is a vast accumulation of shelly sand, an incrustation is deposited on the tidal rocks by the water of the sea, resembling{, as represented in the woodcut,} certain cryptogamic plants (Marchantiae) often seen on damp walls. The surface of the fronds is beautifully glossy; and those parts formed where fully exposed to the light are of a jet black colour, but those shaded under ledges are only grey. I have shown specimens of this incrustation to several geologists, and they all thought that they were of volcanic or igneous origin! In its hardness and translucency—in its polish, equal to that of the finest oliva-shell—in the bad smell given out, and loss of colour under the blowpipe—it shows a close similarity with living sea-shells. Moreover, in sea-shells, it is known that the parts habitually covered and shaded by the mantle of the animal, are of a paler colour than those fully exposed to the light, just as is the case with this incrustation. When we remember that lime, either as a phosphate or carbonate, enters into the composition of the hard parts, such as bones and shells, of all living animals, it is an interesting physiological fact * to find substances harder than the enamel of teeth, and coloured surfaces as well polished as those of a fresh shell, reformed through inorganic means from dead organic matter—mocking, also, in shape, some of the lower vegetable productions.

* Mr. Horner and Sir David Brewster have described (Philosophical Transactions, 1836, p. 65)§ a singular “artificial substance resembling shell.” It is deposited in fine, transparent, highly polished, brown-coloured laminae, possessing peculiar optical properties, on the inside of a vessel, in which cloth, first prepared with glue and then with lime, is made to revolve rapidly in water. It is much softer, more transparent, and contains more animal matter, than the natural incrustation at Ascension; but we here again see the strong tendency which carbonate of lime and animal matter evince to form a solid substance allied to shell.

§ “ On an Artificial Substance Resembling Shell … With an Account of an Examination of the Same.” London, Royal Society: Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society, 1 January, 1836 pp.49-56 (PDF download).

We found on St. Paul's only two kinds of birds—the booby and the noddy. The former is a species of gannet, and the latter a tern. Both are of a tame and stupid disposition, and are so unaccustomed to visitors, that I could have killed any number of them with my geological hammer. The booby lays her eggs on the bare rock; but the tern makes a very simple nest with sea-weed. By the side of many of these nests a small flying-fish was placed; which I suppose, had been brought by the male bird for its partner. It was amusing to watch how quickly a large and active crab (Graspus) {sic, Grapsus}§, which inhabits the crevices of the rock, stole the fish from the side of the nest, as soon as we had disturbed the parent birds. Sir W. Symonds, one of the few persons who have landed here, informs me that he saw the crabs dragging even the young birds out of their nests, and devouring them. Not a single plant, not even a lichen, grows on this islet; yet it is inhabited by several insects and spiders. The following list completes, I believe, the terrestrial fauna: a fly (Olfersia) living on the booby, and a tick which must have come here as a parasite on the birds; a small brown moth, belonging to a genus that feeds on feathers; a beetle (Quedius) and a woodlouse from beneath the dung; and lastly, numerous spiders, which I suppose prey on these small attendants and scavengers of the water-fowl. The often repeated description of the stately palm and other noble tropical plants, then birds, and lastly man, taking possession of the coral islets as soon as formed, in the Pacific, is probably not correct; I fear it destroys the poetry of this story, that feather and dirt-feeding and parasitic insects and spiders should be the first inhabitants of newly formed oceanic land.

§ The spelling error noted above appeared for the first time in Darwin's 1939 Journal and Remarks, and has never been corrected.

The smallest rock in the tropical seas, by giving a foundation for the growth of innumerable kinds of sea-weed and compound animals, supports likewise a large number of fish. The sharks and the seamen in the boats maintained a constant struggle which should secure the greater share of the prey caught by the fishing-lines. I have heard that a rock near the Bermudas, lying many miles out at sea, and at a considerable depth, was first discovered by the circumstance of fish having been observed in the neighbourhood.

FERNANDO {de} NORONHA, Feb. 20th.  —As far as I was enabled to observe, during the few hours we stayed at this place, the constitution of the island is volcanic, but probably not of a recent date. The most remarkable feature is a conical hill, about one thousand feet high, the upper part of which is exceedingly steep, and on one side overhangs its base. The rock is phonolite, and is divided into irregular columns. On viewing one of these isolated masses, at first one is inclined to believe that it has been suddenly pushed up in a semi-fluid state. At St. Helena, however, I ascertained that some pinnacles, of a nearly similar figure and constitution, had been formed by the injection of melted rock into yielding strata, which thus had formed the moulds for these gigantic obelisks. The whole island is covered with wood; but from the dryness of the climate there is no appearance of luxuriance. Half-way up the mountain, some great masses of the columnar rock, shaded by laurel-like trees, and ornamented by others covered with fine pink flowers but without a single leaf, gave a pleasing effect to the nearer parts of the scenery.

—As far as I was enabled to observe, during the few hours we stayed at this place, the constitution of the island is volcanic, but probably not of a recent date. The most remarkable feature is a conical hill, about one thousand feet high, the upper part of which is exceedingly steep, and on one side overhangs its base. The rock is phonolite, and is divided into irregular columns. On viewing one of these isolated masses, at first one is inclined to believe that it has been suddenly pushed up in a semi-fluid state. At St. Helena, however, I ascertained that some pinnacles, of a nearly similar figure and constitution, had been formed by the injection of melted rock into yielding strata, which thus had formed the moulds for these gigantic obelisks. The whole island is covered with wood; but from the dryness of the climate there is no appearance of luxuriance. Half-way up the mountain, some great masses of the columnar rock, shaded by laurel-like trees, and ornamented by others covered with fine pink flowers but without a single leaf, gave a pleasing effect to the nearer parts of the scenery.

BAHIA, OR SAN SALVADOR. BRAZIL, Feb. 29th.  —The day has passed delightfully. Delight itself, however, is a weak term to express the feelings of a naturalist who, for the first time, has wandered by himself in a Brazilian forest. The elegance of the grasses, the novelty of the parasitical plants, the beauty of the flowers, the glossy green of the foliage, but above all the general luxuriance of the vegetation, filled me with admiration. A most paradoxical mixture of sound and silence pervades the shady parts of the wood. The noise from the insects is so loud, that it may be heard even in a vessel anchored several hundred yards from the shore; yet within the recesses of the forest a universal silence appears to reign. To a person fond of natural history, such a day as this brings with it a deeper pleasure than he can ever hope to experience again. After wandering about for some hours, I returned to the landing-place; but, before reaching it, I was overtaken by a tropical storm. I tried to find shelter under a tree, which was so thick that it would never have been penetrated by common English rain; but here, in a couple of minutes, a little torrent flowed down the trunk. It is to this violence of the rain that we must attribute the verdure at the bottom of the thickest woods: if the showers were like those of a colder climate, the greater part would be absorbed or evaporated before it reached the ground. I will not at present attempt to describe the gaudy scenery of this noble bay, because, in our homeward voyage, we called here a second time, and I shall then have occasion to remark on it.

—The day has passed delightfully. Delight itself, however, is a weak term to express the feelings of a naturalist who, for the first time, has wandered by himself in a Brazilian forest. The elegance of the grasses, the novelty of the parasitical plants, the beauty of the flowers, the glossy green of the foliage, but above all the general luxuriance of the vegetation, filled me with admiration. A most paradoxical mixture of sound and silence pervades the shady parts of the wood. The noise from the insects is so loud, that it may be heard even in a vessel anchored several hundred yards from the shore; yet within the recesses of the forest a universal silence appears to reign. To a person fond of natural history, such a day as this brings with it a deeper pleasure than he can ever hope to experience again. After wandering about for some hours, I returned to the landing-place; but, before reaching it, I was overtaken by a tropical storm. I tried to find shelter under a tree, which was so thick that it would never have been penetrated by common English rain; but here, in a couple of minutes, a little torrent flowed down the trunk. It is to this violence of the rain that we must attribute the verdure at the bottom of the thickest woods: if the showers were like those of a colder climate, the greater part would be absorbed or evaporated before it reached the ground. I will not at present attempt to describe the gaudy scenery of this noble bay, because, in our homeward voyage, we called here a second time, and I shall then have occasion to remark on it.

Along the whole coast of Brazil, for a length of at least 2000 miles, and certainly for a considerable space inland, wherever solid rock occurs, it belongs to a granitic formation. The circumstance of this enormous area being constituted of materials which most geologists believe to have been crystallized when heated under pressure, gives rise to many curious reflections. Was this effect produced beneath the depths of a profound ocean? or did a covering of strata formerly extend over it, which has since been removed? Can we believe that any power, acting for a time short of infinity, could have denuded the granite over so many thousand square leagues?

On a point not far from the city, where a rivulet entered the sea, I observed a fact connected with a subject discussed by {Alexander von} Humboldt.* At the cataracts of the great rivers Orinoco, Nile, and Congo, the syenitic rocks are coated by a black substance, appearing as if they had been polished with plumbago. The layer is of extreme thinness; and on analysis by Berzelius it was found to consist of the oxides of manganese and iron. In the Orinoco it occurs on the rocks periodically washed by the floods, and in those parts alone where the stream is rapid; or, as the Indians say, “the rocks are black where the waters are white.” Here the coating is of a rich brown instead of a black colour, and seems to be composed of ferruginous matter alone. Hand specimens fail to give a just idea of these brown burnished stones which glitter in the sun's rays. They occur only within the limits of the tidal waves; and as the rivulet slowly trickles down, the surf must supply the polishing power of the cataracts in the great rivers. In like manner, the rise and fall of the tide probably answer to the periodical inundations; and thus the same effects are produced under apparently different but really similar circumstances. The origin, however, of these coatings of metallic oxides, which seem as if cemented to the rocks, is not understood; and no reason, I believe, can be assigned for their thickness remaining the same.

* Pers. Narr., vol. v., pt. 1., p. 18. {(para. 2) Personal Narrative of Travels to the Equinoctial Regions of the New Continent … . London, 1821: Longman, Hurst et al.}

One day I was amused by watching the habits of the Diodon antennatus, which was caught swimming near the shore. This fish, with its flabby skin, is well known to possess the singular power of distending itself into a nearly spherical form. After having been taken out of water for a short time, and then again immersed in it, a considerable quantity both of water and air is absorbed by the mouth, and perhaps likewise by the branchial orifices. This process is effected by two methods: the air is swallowed, and is then forced into the cavity of the body, its return being prevented by a muscular contraction which is externally visible: but the water enters in a gentle stream through the mouth, which is kept wide open and motionless; this latter action must, therefore, depend on suction. The skin about the abdomen is much looser than that on the back; hence, during the inflation, the lower surface becomes far more distended than the upper; and the fish, in consequence, floats with its back downwards. Cuvier doubts whether the Diodon in this position is able to swim; but not only can it thus move forward in a straight line, but it can turn round to either side. This latter movement is effected solely by the aid of the pectoral fins; the tail being collapsed, and not used. From the body being buoyed up with so much air, the branchial openings are out of water, but a stream drawn in by the mouth constantly flows through them.

The fish, having remained in this distended state for a short time, generally expelled the air and water with considerable force from the branchial apertures and mouth. It could emit, at will, a certain portion of the water, and it appears, therefore, probable that this fluid is taken in partly for the sake of regulating its specific gravity. This Diodon possessed several means of defence. It could give a severe bite, and could eject water from its mouth to some distance, at the same time making a curious noise by the movement of its jaws. By the inflation of its body, the papillae, with which the skin is covered, become erect and pointed. But the most curious circumstance is, that it secretes from the skin of its belly, when handled, a most beautiful carmine-red fibrous matter, which stains ivory and paper in so permanent a manner that the tint is retained with all its brightness to the present day: I am quite ignorant of the nature and use of this secretion. I have heard from Dr. Allan of Forres, that he has frequently found a Diodon, floating alive and distended, in the stomach of the shark, and that on several occasions he has known it eat its way, not only through the coats of the stomach, but through the sides of the monster, which has thus been killed. Who would ever have imagined that a little soft fish could have destroyed the great and savage shark?

March 18th.—We sailed from Bahia. A few days afterwards, when not far distant from the Abrolhos Islets,  my attention was called to a reddish-brown appearance in the sea. The whole surface of the water, as it appeared under a weak lens, seemed as if covered by chopped bits of hay, with their ends jagged. These are minute cylindrical confervae, in bundles or rafts of from twenty to sixty in each. Mr. Berkeley informs me that they are the same species (Trichodesmium erythraeum) with that found over large spaces in the Red Sea, and whence its name of Red Sea is derived. * Their numbers must be infinite: the ship passed through several bands of them, one of which was about ten yards wide, and, judging from the mud-like colour of the water, at least two and a half miles long. In almost every long voyage some account is given of these confervae. They appear especially common in the sea near Australia; and off Cape Leeuwin I found an allied but smaller and apparently different species. Captain Cook, in his third voyage, remarks, that the sailors gave to this appearance the name of sea-sawdust.

my attention was called to a reddish-brown appearance in the sea. The whole surface of the water, as it appeared under a weak lens, seemed as if covered by chopped bits of hay, with their ends jagged. These are minute cylindrical confervae, in bundles or rafts of from twenty to sixty in each. Mr. Berkeley informs me that they are the same species (Trichodesmium erythraeum) with that found over large spaces in the Red Sea, and whence its name of Red Sea is derived. * Their numbers must be infinite: the ship passed through several bands of them, one of which was about ten yards wide, and, judging from the mud-like colour of the water, at least two and a half miles long. In almost every long voyage some account is given of these confervae. They appear especially common in the sea near Australia; and off Cape Leeuwin I found an allied but smaller and apparently different species. Captain Cook, in his third voyage, remarks, that the sailors gave to this appearance the name of sea-sawdust.

* M. Montagne, in Comptes Rendus, etc., Juillet, 1844; and Annal. des Scienc. Nat., Dec. 1844

Near Keeling Atoll,§ in the Indian Ocean, I observed many little masses of confervae a few inches square, consisting of long cylindrical threads of excessive thinness, so as to be barely visible to the naked eye, mingled with other rather larger bodies, finely conical at both ends. {Two of these are shown in the woodcut united together.} They vary in length from .04 to .06, and even to .08 of an inch in length; and in diameter from .006 to .008 of an inch. Near one extremity of the cylindrical part, a green septum, formed of granular matter, and thickest in the middle, may generally be seen. This, I believe, is the bottom of a most delicate, colourless sac, composed of a pulpy substance, which lines the exterior case, but does not extend within the extreme conical points. In some specimens, small but perfect spheres of brownish granular matter supplied the places of the septa; and I observed the curious process by which they were produced. The pulpy matter of the internal coating suddenly grouped itself into lines, some of which assumed a form radiating from a common centre; it then continued, with an irregular and rapid movement, to contract itself, so that in the course of a second the whole was united into a perfect little sphere, which occupied the position of the septum at one end of the now quite hollow case. The formation of the granular sphere was hastened by any accidental injury. I may add, that frequently a pair of these bodies were attached to each other, as represented above, cone beside cone, at that end where the septum occurs.

They vary in length from .04 to .06, and even to .08 of an inch in length; and in diameter from .006 to .008 of an inch. Near one extremity of the cylindrical part, a green septum, formed of granular matter, and thickest in the middle, may generally be seen. This, I believe, is the bottom of a most delicate, colourless sac, composed of a pulpy substance, which lines the exterior case, but does not extend within the extreme conical points. In some specimens, small but perfect spheres of brownish granular matter supplied the places of the septa; and I observed the curious process by which they were produced. The pulpy matter of the internal coating suddenly grouped itself into lines, some of which assumed a form radiating from a common centre; it then continued, with an irregular and rapid movement, to contract itself, so that in the course of a second the whole was united into a perfect little sphere, which occupied the position of the septum at one end of the now quite hollow case. The formation of the granular sphere was hastened by any accidental injury. I may add, that frequently a pair of these bodies were attached to each other, as represented above, cone beside cone, at that end where the septum occurs.

§ See Darwin's Chapter XX; Keeling Island.

I will add here a few other observations connected with the discoloration of the sea from organic causes. On the coast of Chile, a few leagues north of Concepcion, the Beagle one day passed through great bands of muddy water, exactly like that of a swollen river; and again, a degree south of Valparaiso, when fifty miles from the land, the same appearance was still more extensive. Some of the water placed in a glass was of a pale reddish tint; and, examined under a microscope, was seen to swarm with minute animalcula darting about, and often exploding. Their shape is oval, and contracted in the middle by a ring of vibrating curved ciliae. It was, however, very difficult to examine them with care, for almost the instant motion ceased, even while crossing the field of vision, their bodies burst. Sometimes both ends burst at once, sometimes only one, and a quantity of coarse, brownish, granular matter was ejected. The animal an instant before bursting expanded to half again its natural size; and the explosion took place about fifteen seconds after the rapid progressive motion had ceased: in a few cases it was preceded for a short interval by a rotatory movement on the longer axis. About two minutes after any number were isolated in a drop of water, they thus perished. The animals move with the narrow apex forwards, by the aid of their vibratory ciliae, and generally by rapid starts. They are exceedingly minute, and quite invisible to the naked eye, only covering a space equal to the square of the thousandth of an inch. Their numbers were infinite; for the smallest drop of water which I could remove contained very many. In one day we passed through two spaces of water thus stained, one of which alone must have extended over several square miles. What incalculable numbers of these microscopical animals! The colour of the water, as seen at some distance, was like that of a river which has flowed through a red clay district, but under the shade of the vessel's side it was quite as dark as chocolate. The line where the red and blue water joined was distinctly defined. The weather for some days previously had been calm, and the ocean abounded, to an unusual degree, with living creatures.*

* M. Lesson (Voyage de la Coquille, tom. i., p. 255) mentions red water off Lima, apparently produced by the same cause. Peron, the distinguished naturalist, in the Voyage aux Terres Australes, gives no less than twelve references to voyagers who have alluded to the discoloured waters of the sea (vol. ii. p. 239). To the references given by Peron may be added, Humboldt's Pers. Narr., vol. vi. {part 2,} p. 804; Flinder's Voyage, vol. i. p. 92; Labillardiere, vol. i. p. 287; Ulloa's Voyage; Voyage of the Astrolabe and of the Coquille; Captain King's Survey of Australia, etc.

In the sea around Tierra del Fuego, and at no great distance from the land, I have seen narrow lines of water of a bright red colour, from the number of crustacea, which somewhat resemble in form large prawns. The sealers call them whale-food. Whether whales feed on them I do not know; but terns, cormorants, and immense herds of great unwieldy seals derive, on some parts of the coast, their chief sustenance from these swimming crabs. Seamen invariably attribute the discoloration of the water to spawn; but I found this to be the case only on one occasion. At the distance of several leagues from the Archipelago of the Galapagos, the ship sailed through three strips of a dark yellowish, or mud-like water; these strips were some miles long, but only a few yards wide, and they were separated from the surrounding water by a sinuous yet distinct margin. The colour was caused by little gelatinous balls, about the fifth of an inch in diameter, in which numerous minute spherical ovules were imbedded: they were of two distinct kinds, one being of a reddish colour and of a different shape from the other. I cannot form a conjecture as to what two kinds of animals these belonged. Captain Colnett remarks, that this appearance is very common among the Galapagos Islands, and that the directions of the bands indicate that of the currents; in the described case, however, the line was caused by the wind. The only other appearance which I have to notice, is a thin oily coat on the water which displays iridescent colours. I saw a considerable tract of the ocean thus covered on the coast of Brazil; the seamen attributed it to the putrefying carcase of some whale, which probably was floating at no great distance. I do not here mention the minute gelatinous particles, hereafter to be referred to, which are frequently dispersed throughout the water, for they are not sufficiently abundant to create any change of colour.

There are two circumstances in the above accounts which appear remarkable: first, how do the various bodies which form the bands with defined edges keep together? In the case of the prawn-like crabs, their movements were as co-instantaneous as in a regiment of soldiers; but this cannot happen from anything like voluntary action with the ovules, or the confervae, nor is it probable among the infusoria. Secondly, what causes the length and narrowness of the bands? The appearance so much resembles that which may be seen in every torrent, where the stream uncoils into long streaks the froth collected in the eddies, that I must attribute the effect to a similar action either of the currents of the air or sea. Under this supposition we must believe that the various organized bodies are produced in certain favourable places, and are thence removed by the set of either wind or water. I confess, however, there is a very great difficulty in imagining any one spot to be the birthplace of the millions of millions of animalcula and confervae: for whence come the germs at such points?—the parent bodies having been distributed by the winds and waves over the immense ocean. But on no other hypothesis can I understand their linear grouping. I may add that Scoresby remarks that green water abounding with pelagic animals is invariably found in a certain part of the Arctic Sea.

CHAPTER II

RIO DE JANEIRO

Rio de Janeiro—Excursion north of Cape Frio—Great Evaporation—Slavery—Botofogo Bay—Terrestrial Planariae—Clouds on the Corcovado—Heavy Rain—Musical Frogs—Phosphorescent Insects—Elater, springing powers of—Blue Haze—Noise made by a Butterfly—Entomology—Ants—Wasp killing a Spider—Parasitical Spider—Artifices of an Epeira—Gregarious Spider—Spider with an unsymmetrical Web.

APRIL 4th to July 5th, 1832.—A few days after our arrival  {at Rio de Janeiro} I became acquainted with an Englishman who was going to visit his estate, situated rather more than a hundred miles from the capital, to the northward of Cape Frio.§

{at Rio de Janeiro} I became acquainted with an Englishman who was going to visit his estate, situated rather more than a hundred miles from the capital, to the northward of Cape Frio.§  I gladly accepted his kind offer of allowing me to accompany him.

I gladly accepted his kind offer of allowing me to accompany him.

§ Darwin makes no further mention of Cape Frio, so it is unclear if he actually passed through it. However, it is on the route to Campos Novos and beyond, and so it is included in the Google Earth view.

April 8th.—Our party amounted to seven. The first stage was very interesting. The day was powerfully hot, and as we passed through the woods, everything was motionless, excepting the large and brilliant butterflies, which lazily fluttered about. The view seen when crossing the hills behind Praia Grande was most beautiful; the colours were intense, and the prevailing tint a dark blue; the sky and the calm waters of the bay vied with each other in splendour. After passing through some cultivated country, we entered a forest, which in the grandeur of all its parts could not be exceeded. We arrived by midday at Ithacaia; {Itacoatiara?}  this small village is situated on a plain, and round the central house are the huts of the negroes. These, from their regular form and position, reminded me of the drawings of the Hottentot habitations in Southern Africa. As the moon rose early, we determined to start the same evening for our sleeping-place at the Lagoa Marica.

this small village is situated on a plain, and round the central house are the huts of the negroes. These, from their regular form and position, reminded me of the drawings of the Hottentot habitations in Southern Africa. As the moon rose early, we determined to start the same evening for our sleeping-place at the Lagoa Marica.  As it was growing dark we passed under one of the massive, bare, and steep hills of granite which are so common in this country. This spot is notorious from having been, for a long time, the residence of some runaway slaves, who, by cultivating a little ground near the top, contrived to eke out a subsistence. At length they were discovered, and a party of soldiers being sent, the whole were seized with the exception of one old woman, who, sooner than again be led into slavery, dashed herself to pieces from the summit of the mountain. In a Roman matron this would have been called the noble love of freedom: in a poor negress it is mere brutal obstinacy. We continued riding for some hours. For the few last miles the road was intricate, and it passed through a desert waste of marshes and lagoons. The scene by the dimmed light of the moon was most desolate. A few fireflies flitted by us; and the solitary snipe, as it rose, uttered its plaintive cry. The distant and sullen roar of the sea scarcely broke the stillness of the night.

As it was growing dark we passed under one of the massive, bare, and steep hills of granite which are so common in this country. This spot is notorious from having been, for a long time, the residence of some runaway slaves, who, by cultivating a little ground near the top, contrived to eke out a subsistence. At length they were discovered, and a party of soldiers being sent, the whole were seized with the exception of one old woman, who, sooner than again be led into slavery, dashed herself to pieces from the summit of the mountain. In a Roman matron this would have been called the noble love of freedom: in a poor negress it is mere brutal obstinacy. We continued riding for some hours. For the few last miles the road was intricate, and it passed through a desert waste of marshes and lagoons. The scene by the dimmed light of the moon was most desolate. A few fireflies flitted by us; and the solitary snipe, as it rose, uttered its plaintive cry. The distant and sullen roar of the sea scarcely broke the stillness of the night.

April 9th.—We left our miserable sleeping-place before sunrise. The road passed through a narrow sandy plain, lying between the sea and the interior salt lagoons. The number of beautiful fishing birds, such as egrets and cranes, and the succulent plants assuming most fantastical forms, gave to the scene an interest which it would not otherwise have possessed. The few stunted trees were loaded with parasitical plants, among which the beauty and delicious fragrance of some of the orchideae were most to be admired. As the sun rose, the day became extremely hot, and the reflection of the light and heat from the white sand was very distressing. We dined at Mandetiba;§  the thermometer in the shade being 84°. The beautiful view of the distant wooded hills, reflected in the perfectly calm water of an extensive lagoon, quite refreshed us. As the vênda * here was a very good one, and I have the pleasant, but rare remembrance, of an excellent dinner, I will be grateful and presently describe it, as the type of its class. These houses are often large, and are built of thick upright posts, with boughs interwoven, and afterwards plastered. They seldom have floors, and never glazed windows; but are generally pretty well roofed. Universally the front part is open, forming a kind of verandah, in which tables and benches are placed. The bed-rooms join on each side, and here the passenger may sleep as comfortably as he can, on a wooden platform, covered by a thin straw mat. The vênda stands in a courtyard, where the horses are fed. On first arriving it was our custom to unsaddle the horses and give them their Indian corn; then, with a low bow, to ask the Senhôr to do us the favour to give us something to eat. “Anything you choose, sir” was his usual answer. For the few first times, vainly I thanked providence for having guided us to so good a man. The conversation proceeding, the case universally became deplorable.

the thermometer in the shade being 84°. The beautiful view of the distant wooded hills, reflected in the perfectly calm water of an extensive lagoon, quite refreshed us. As the vênda * here was a very good one, and I have the pleasant, but rare remembrance, of an excellent dinner, I will be grateful and presently describe it, as the type of its class. These houses are often large, and are built of thick upright posts, with boughs interwoven, and afterwards plastered. They seldom have floors, and never glazed windows; but are generally pretty well roofed. Universally the front part is open, forming a kind of verandah, in which tables and benches are placed. The bed-rooms join on each side, and here the passenger may sleep as comfortably as he can, on a wooden platform, covered by a thin straw mat. The vênda stands in a courtyard, where the horses are fed. On first arriving it was our custom to unsaddle the horses and give them their Indian corn; then, with a low bow, to ask the Senhôr to do us the favour to give us something to eat. “Anything you choose, sir” was his usual answer. For the few first times, vainly I thanked providence for having guided us to so good a man. The conversation proceeding, the case universally became deplorable.

“Any fish can you do us the favour of giving?”—

“Oh! no, sir.”—

“Any soup?”—

“No, sir.”—

“Any bread?”—

“Oh! no, sir.”—

“Any dried meat?”—

“Oh! no, sir.”

§ Location uncertain, but presumably on the southern shore of Lagoa de Saquarema.

* Vênda, the Portuguese name for an inn.

If we were lucky, by waiting a couple of hours, we obtained fowls, rice, and farinha. It not unfrequently happened, that we were obliged to kill, with stones, the poultry for our own supper. When, thoroughly exhausted by fatigue and hunger, we timorously hinted that we should be glad of our meal, the pompous, and (though true) most unsatisfactory answer was, “It will be ready when it is ready.” If we had dared to remonstrate any further, we should have been told to proceed on our journey, as being too impertinent. The hosts are most ungracious and disagreeable in their manners; their houses and their persons are often filthily dirty; the want of the accommodation of forks, knives, and spoons is common; and I am sure no cottage or hovel in England could be found in a state so utterly destitute of every comfort. At Campos Novos,  however, we fared sumptuously; having rice and fowls, biscuit, wine, and spirits, for dinner; coffee in the evening, and fish with coffee for breakfast. All this, with good food for the horses, only cost 2s. 6d. per head. Yet the host of this vênda, being asked if he knew anything of a whip which one of the party had lost, gruffly answered, “How should I know? why did you not take care of it?—I suppose the dogs have eaten it.”

however, we fared sumptuously; having rice and fowls, biscuit, wine, and spirits, for dinner; coffee in the evening, and fish with coffee for breakfast. All this, with good food for the horses, only cost 2s. 6d. per head. Yet the host of this vênda, being asked if he knew anything of a whip which one of the party had lost, gruffly answered, “How should I know? why did you not take care of it?—I suppose the dogs have eaten it.”

Leaving Mandetiba, we continued to pass through an intricate wilderness of lakes; in some of which were fresh, in others salt water shells. Of the former kinds, I found a Limnaea in great numbers in a lake, into which, the inhabitants assured me that the sea enters once a year, and sometimes oftener, and makes the water quite salt. I have no doubt many interesting facts, in relation to marine and fresh water animals, might be observed in this chain of lagoons, which skirt the coast of Brazil. M. Gay * has stated that he found in the neighbourhood of Rio, shells of the marine genera solen and mytilus, and fresh water ampullariae, living together in brackish water. I also frequently observed in the lagoon near the Botanic Garden, where the water is only a little less salt than in the sea, a species of hydrophilus, very similar to a water-beetle common in the ditches of England: in the same lake the only shell belonged to a genus generally found in estuaries.

* Annales des Sciences Naturelles for 1833.