|

PITCAIRN'S ISLAND,ANDTHE ISLANDERS,IN 1850.BY WALTER BRODIE,AUTHOR OF "THE FAST AND PRESENT STATE OF NEW ZEALAND."TOGETHER WITH EXTRACPS FROM HISPRIVATE JOURNAL,ANDA FEW HINTS UPON CALIFORNIA;ALSO,THE REPORTS OF AIL THE COMMANDERS OF H. M. SHIPS THAT HAVE

|

ENTERED AT STATIONERS' HALL. |

|

PREFACE.In the month of March, 1850, I happened to be left upon Pitcairn's Island, the vessel from which I landed having been blown off the island during the night. Four other gentlemen, fellow-passengers, were likewise in the same predicament with myself, our worldly possessions consisting of the clothes we stood up in, whilst the chances of our being able to pursue our journey within any reasonable time were quite uncertain. Thrown thus upon the hospitality of the islanders, avowedly destitute of the means of making them any return, we were not only received with the most cordial welcome, but treated with a prevenance of attention (the offspring of natural politeness) which could not have been exceeded in the most polished European society, and which enables me, in spite of the disappointed |

object of my voyage, to reckon those few weeks among the happiest of my life. My time was principally occupied in gathering materials for an account of this virtuous and interesting community, which I feel myself bound to make public, in hope that it may draw attention, now more than ever needed, to their condition, and thus partially discharge the obligation which my fellow-passengers and myself have incurred.

WALTER BRODIE.

|

DIARY.March 23rd, 1850. At 10 P.M. sighted Pitcairn's island twenty-five miles to the westward of us, scarcely visible. But for the moon, which was immediately above it, I do not think we should have seen it. This island is memorable as affording a refuge to the mutineers of H.M.S. Bounty. Our captain thinking it advisable to procure some water if possible, bore up for the island, having only 700 gallons of water fit for drinking on board. During the night we dodged about under easy sail to windward of the island. March 24th. Sunday, at daylight we found ourselves off the settlement, which is on the north aide of the island, but for some time no notice appeared to be taken of us on the island. At 8 A.M. we saw a red flag hoisted near the precipice in front of the settlement; tacked skip and stood in towards the island, when we perceived a boat coming from the shore under sail, which proved to be a whale boat with nine islanders in it. After going through the usual ceremonies of putting innumerable questions to each other, we prepared to go on shore. The captain asked them to get some water off immediately; but they objected to do so, as it was Sunday, telling him, however, that if it were a matter of necessity, they would bring him off a little, which they |

did, about 180 gallons during the day. They all strongly recommended the captain to anchor, as several vessels lately requiring water had done so; but he told them it was too much trouble hauling up the chains and bending them, a trouble which he might easily have overcome in about half an hour, as they were quite handy. The fact is, there was a sort of supercargo on board, who appeared to have more to say about it than the captain, and who ultimately carried his point in not anchoring the vessel. Had the captain acted in a manner which he thought would have benefitted the owners, and not have listened to the opinions of a boy, who knew as much about his supercargoship as he did about the expediting of the vessel, he would have saved much time and expense. At 10 A.M. the islanders took their departure to procure the water, and the ship's boat went on shore – the captain, Mr. Webster, Mr. Carleton, Mr. Taylor, and myself, with an islander to pilot us through the surf to the landing-place. Upon landing we were met by a few islanders, the remainder being at church. After conversing with them at the landing for some twenty minutes, the captain made up his mind to remain off the island under easy sail until the next day, to enable him to complete his watering, and to procure fruit, potatoes, &c., &c. We then made a start for the settlement, ascending a very steep hill at an angle of forty-five degrees, which was very slippery after the rain, which fell very heavily in the morning, the first that had fallen here for two months. After climbing about 200 feet, and then getting over a stile, |

which was placed to prevent the cattle from approaching the settlement, we came to the market-place, a small open space aurrounded by cocoa-nut trees; and a few hundred yards farther, came to the village, to which the inhabitants have not at present given a name. It is very prettily placed, with a lovely view of the sea between the trees. In passing the church we fouud that the service had only just commenced. I propoaed accordingly that we should join in it, and in a few minutes we were all in prayer among the islanders. Upon our going into this neat little church, the congregation did not appear so full of curiosity as might have been expected; hardly any so much as turned round to see whom we were like. During the service the marriage ceremony was performed between two young persons, who seemed rather bashful on the occasion, which, I preaume, waa on account of so many strangers being present. Lydia Young and Daniel M'Coy were the names of the happy couple. After church was over, we all congratulated the happy couple, and shook hands with every one, wbich took some time. After introducing ourselves to Mr. Nobbs, the minister, we proceeded to his house, where we ate some fruit, and then took a walk about the island. About 3 P.M. one of the islanders reported that our vessel, the barque Noble, had carried away her fore-yard, which we thought strange, as there had been but little wind during the morning; but which atill might have been possible, as we had sprung it badly before arriving at Pitcairn's Island. After a short time, however, we saw the vessel |

under easy sail, showing no signs of any mishap. After our walk, our captain and Mr. Supercargo left a list of articles required for the Noble, which the islanders promised to take off on the morrow. They then took their leave of us all, as they intended sleeping on board the barque Noble that night. Previous to their leaving us, they both, especially the captain, gave us leave to remain on shore all night, in presence of nearly all the islanders, stating at the same time that they were going to take off an islander with them, of the name of Matthew Quintal, and bidding us be ready to go on board the following morning. We now mustered five passengers on shore, two others having come on shore in a shore boat. March 25th. Strong east wind with rain at times, no appearance of the Noble. Employed myself all day in collecting information relative to the island. At 5 P.M. Mr. Carleton, an islander, and myself walked up to the top of the look-out range, which is rather more than 1000 feet above the level of the sea. We looked for some time before we could see any vessel; at last we saw the Noble about fifteen miles to leeward of the island, on the starboard tack, trying to gain the island. We wished to get off to her, but the islanders said there was too much wind; in fact, the surf was running so high at the landing-place, that we could not have gone through it. March 26th. Strong breezes from the S.E. and squally with much rain; no vessel in sight, the weather being very thick and hazy. Employed myself as yesterday. |

|

pose of making money by the disposai of his produce, so that the nice distinction which he drew as to the means of acquiring it, deserves to be only the more highly appreciated. March 27th. Fine clear weather this day; it had cleared up about 2 A.M. with a light wind from N.N.W. At noon the vessel was seen from the look-out range, about forty miles to the north-west of the island, standing to the eastward. We were ail highly delighted at this news, as we feared yesterday that she might have been blown off; we now expected her close in with the island tbe next morning, and made the necessary preparations. In the afternoon, Mr. Carleton, John Adams, and myself went to the east side of the island, to try and get to a place where there were some unknown characters, supposed to have been cut into the solid rock by the original inhabitants of the island. It was called the Rope – a rope having been used in former days to descend the precipice. Upon our arrival at the edge of the perpendicular cliff, we did not like the look of it: it was a very dizzy height of nearly 600 feet perpendicular; broken necks would have been the inevitable consequence of missing a single step. Adams strongly dissuaded us, on account of the slippery state of the ground, from attempting it; we, therefore, returned home again with disappointed curiosity. On our way home we visited the height called St. Paul's, which is the northeast point of the island, and from which we again saw our vessel. March 28th. Fine clear weather, with a light north |

wind, which increased at noon to a moderate breeze. At daylight we were all on the qui vive, expecting to see the Noble close in to the island; when, to our surprise, we found that she was about twenty miles to the northward, still standing to the eastward. On looking at her through the glass (there being two excellent ones on the island), she appeared to have no foresail, foretopsail, or fore-top-gallant-sail set, but all her head-sails set. As the sun was shining upon her, we could see her very distinctly. Our observations all agreeing relative to her sails, we came to the conclusion that she must be fishing her sprung fore-yard, or repairing whatever damage she might have sustained on the Sunday, supposing the native report, already mentioned, to have been correct. From her situation, we, of course, assumed her to be the Noble; but from the course she was steering, I thought it probable that she might have had no sail on her foremast yesterday, and that, instead of her sailing towards the island during the night, she had actually drifted so much nearer to us, by making lee-way. As the wind was likely to come from the eastward, I thought she intended to get well to the eastward before she came down to take us on board, as she was in a partially crippled state. At 10 A.M. she was a little to the eastward of the island. At 11 A.M. we all proposed going off to her in whale boats belonging to the island. The islanders would have willingly pulled us out, although to so great a distance, had she showed any inclination to wait for us. But no such inclination was displayed; and as the wind was now increasing, it |

would have been folly to think of catching her. At noon the wind veered to the south-east, when she steered to the north-east, and in about an hour was out of sight, leaving us totally unable to account for her proceedings. My own opinion is, that she remained by the island until Tuesday night, when the weather appeared very unsettled, and the captain thinking there was no chance of beating to windward in such a hulk of a vessel, shaped his course for California. But previously, I have no doubt that Mr. Webster (better known as a shopman behind the counter at Gibson and Mitchell's retail store in Auckland) had urged him to pursue this course; at the same time giving him (the captain) an instrument in writing, exonerating him from any blame or expense attending it, thinking that our expenses in getting away from the island, &c., &c., would be far less than the enormous difference which the detention in trying to make the island might make in the sale of the Noble's cargo – a cargo which was partially perishable. Time, I suppose, will explain everything. Should this barque not have been the Noble, and the Noble have been drifted to the westward by the easterly winds of Monday and Tuesday last, she had now ample time for regaining her lost ground by the N.N.w. and N. winds, whicb had been. blowing for many hours. But my firm belief is that the vessel we saw this day was the barque Noble, and that she steered for California on Tuesday night; and that, after steering some few hours to the northward, she met with the northerly winds, which compelled her to steer to the eastward, when she |

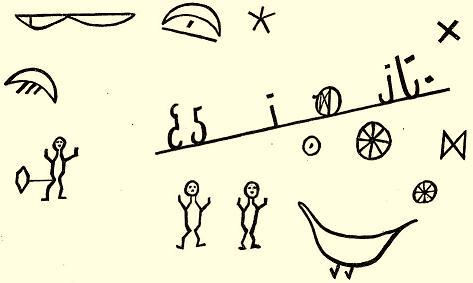

again came most unwillingly in sight of the island. From her position last night, and also this morning, she must have been close hauled, or nearly so, and must have made about four points lee-way, being a very dull sailer; and having no square rails on ber foremast, she must have drifted bodily to leeward during the night. I have no doubt that, at daylight this morning, they were much surprised on board the Noble at seeing their positien, but could not prevent our seeing them; and that, as they must have made up their minds to leave us, they did not think it worth their while to come down for us, which would not have detained them three hours, or, at the utmost, four hours. It is possible that they did not imagine that we saw them so clearly as was the case. Here we were, five of us, left upon an island, without a change of clothes or linen, and not a sixpence in our pockets; but, luckily for us, left, perhaps, with little doubt, upon the most moral and religious island in the world, and amongat the most kind-hearted, hospitable, and generous islanders ever met with. Hearing that there was another road to the hieroglyphics, rather more circuitous than the one we attempted yesterday in vain, and not of quite so dangerous a nature, Carleton, Adams, and myself made another attempt to reach them. Upon arriving at the edge of the precipice, it was an awful-looking place to go down; but, if anything, rather more easy to the eye than the other road. The first hundred yards we slid down in a sitting position, on our haunches, having but little regard for the seat of our trousers, a part of which we expected every moment |

would leave us. We then came to a place, in my opinion, far worse than what we looked at yesterday it was a ledge of rock, about ten feet long, and of only a few inches in breadth. I must say it made me feel rather nervous; but our guide having told us that it was the worst place we had to cross, I hurried over it as quickly as I could, but with as much caution as possible. Adams persuading us that there was no danger, I did not agree with him. To him it was nothing; he skipped across just like a goat. It is extraordinary to see these islanders go up and down the precipices, and jump from rock to rock, like so many goats. After crossing this bad place, the remainder of our journey down to the sea was still very steep; but, with a few resting-places to recover breath, we reached the sea-shore at last in safety, with no other damage than a few scratches and broken trousers. We then proceeded along the coast for about one-third of a mile. The walking here was very bad, it being over large and loose rocks; fortunately it was low water, or I should have had to swim round a headland that formed one side of the bay – an exercise at which I am not very expert. We now arrived at the spot which had cost us so much trouble and anxiety to reach. The hieroglyphics were carved at from two to ten feet from the ground, many of them appearing to be nearly obliterated. The rock in which they were cut was exceedingly hard, and much resembled the French burr stone. On the opposite page is an accurate representation of what we saw – the moon, the sun, the stars, a bird, figures of men, &c., &c. After remaining about an |

|

hour, we returned home; not by the same way we came, but by the road which we attempted yesterday, which made a difference of nearly a mile in shortening the distance. Adams took the lead, with a rope and a hoe in his hand, making holes in the ground and soft rock, wherever they could be made to our advantage, in ascending this anything but delightful ascent. When nearly up to the top of the first ridge, I squeezed myself between two rocks to rest, and then requested Adams to pass the rope down to fasten round my waist, as immediately above me the rocks were perpendicular; and having a rope, I thought I might as well make use of it. Adams then hauled, or I should say assisted, me up this difficult pass. Carleton would not use the rope, preferring his own hands and feet to the assistance of others. Upon arriving here, which was the place we looked down upon yesterday, I was most thankful. How curiosity could have tempted me to undertake so dangerous an excursion, I know not; but I do strongly recommend Europeans never to attempt the same for the sake of curiosity. The only strangers that ever attempted and accomplished it besides ourselves were Dr. Domet, Lieutenant M‘Leod, and Mr. Lock, of H.M.S. Calypso. These figures can be visited in a canoe or boat; but only in very fine weather, on account of the great surf running on that side of the island. In the evening there was no appearance of any vessel in sight. I myself gave up all hope of the barque Noble, but the others did not, thinking that she had gone to Elizabeth Island to procure a spar for a fore-yard. Elizabeth, or Henderson's |

Island, is about 120 miles from Pitcairn's – latitude, 24° 0' 2" south; longitude, 124° 45' west – is larger than Pitcairn's, and covered with timber of only a small size, similar to that with which the houses are built upon Pitcairn's, and which is nearly all used up. Not long ago, eleven of these islanders, along with John Evans (one of the three resident Europeans), were carried to Henderson's, or Elizabeth Island, in an American whaling vessel, on an exploring expedition. The landing was anything but good, and the soil not near so rich as that of their own island, being of a much more sandy nature. Water there appeared to be none; but, after a long searcb, they found a fresh-water spring below highwater mark. Some cocoa-nuts, which had been purposely carried there, were planted upon the best ground they could find. Several goats had been likewise shipped for turning out, but were actually forgotten until some time after they were returned on board. They were only a few hours on the island, and, therefore; were unable to form or give any detailed description of it. Elizabeth Island is of a peculiar formation, very few instances of which are known; viz., dead coral, more or less porous, elevated in a flat surface, probably by volcanic agency, to the height of eighty feet. It is five miles in length, one in breadth, and thickly covered with shrubs, which makes it difficult to climb. It was called Henderson's Island after the captain of the ship Hercules of Calcutta, though first visited by the crew of the Essex, an American whaler, two of whom landed on it after the loss of their ship, and were subsequently |

taken off by an English whaler, who heard of their fate at Valparaiso. They are very anxious to procure a small vessel or large boat, of about twenty tons burden, to enable them to visit this island at pleasure, and bring off house-timber as required, as likewise to couvert it into a run for their live stock; thus relieving their little island from that burden, and enabling them to direct the whole of its capabilities to the use of man. They have established a sort of Bank amongst themselves, in which a large part of the money paid by vessels for refreshments, is suffered to accumulate for the purpose of purchasing a small vessel. March 29th. Good Friday. This day is the only fast observed here during the year. There are two services in the church. Wind from N.N.W. to N.N.E. and fine clear weather. Much talking among the islanders regarding the Noble and our situation. They are greatly annoyed at young Quintal's being taken away in the vessel. It is curions that this same Quintal has repeatedly spoken when at home of his great desire to visit California, provided that he could be blown off the island in some vessel, so as to spare him the pain of taking leave of his friends and family. I certainly never saw family ties so closely drawn as they are here. March 30th. This day I was shown two-guns (nine-pounders), one large copper boiler, several pegs of iron kentledge, part of an armourer's bellows, an anvil, two sledge hammers, and a quantity of loose copper, which came out of the Bounty. Moderate north wind during the day. Employed myself in collecting information |

regarding this island, as also in collecting shells, which were not very numerous. Took some lessons in tappa-making, under Mrs. Nobbs and her married daughter's tuition. It being a very noisy process I did not remain long a scholar at my lesson. The tappa cloth is used by the islanders in place of sheets. Before they received presents from the British Government in clothing, &c., &c., they used it for their ordinary clothing. This day my tobacco was reduced to only one pipe full, which to me was the greatest possible deprivation. In the evening Mr. Nobbs found a stick of tobacco in his medicine chest, which I accepted from him as a very great prize. Nearly all the men here smoke, but there is not more, than half a pound of tobacco upon the whole island. This day an unfortunate accident was discovered. The bull which had been imported by H.M.S. Daphne was found dead, having fallen over the rocks, the soft ground having given way under its weight. March 31st. Moderate east wind, with fine clear weather. Went twice to church and attended the Sunday-school. April 1st. Wind and weather as yesterday. This day a general meeting was held in the church, to take our case into consideration, the result and minutes of which we did not hear. Papers were also signed by the majority of the islanders who were present when Captain Parker gave us all leave to sleep on shore, promising at the same time to take us all off the next morning, and also by those islanders that particularly watched the Noble on the 21st ultimo. Viewed the remaining |

relics of the Bounty. A new house having been built for John Adams, which had never been occupied, Carleton proposed that we should all go into it, and keep house for ourselves, so as to relieve our individual hosts from our maintenance, although we should still be dependent upon the community for an occasional basket of yams, &c., &c. We all agreed but one (Baron de Therry) to Carleton's proposai; as such an arrangement would likewise make us more independent, and enable us to keep our own hours without disturbing any one, as well as allow our hosts and hostesses to take possession of their own sleeping apartments, which they had given up to us from the time we came on shore. Our hosts would not listen to our keeping house for ourselves, neither did they at all like our sleeping out of their houses. But after a good deal of battling, we agreed to take our meals with them as usual, which was the only way by which we could compromise the matter. I then told Mr. and Mrs. Nobbs that they must give up treating me as a guest, and allow me to live just like themselves, in their ordinary way. I offered to assist him in his plantations, which he appeared rather hurt at. I shall not forget a remark that Adams (the eider) made to Carleton, when he offered to work in his plantation. He said, "that now he had three times more pleasure in seeing him in his house than before; for that while the ship was there he might have supposed that he looked for some return, whereas now it was quite clear that he could make none." They appeared to rack their ingenuity in trying to put us at our ease, and |

to make us believe that the advantage was upon their aide, and that with a delicacy and natural good breeding which it was refreshing to witness. Towards evening oranges, pine-apples, bananas, plantains, &c., &c., came raining in upon us, together with two large baga of new clothes, voted at the meeting, into which we were to dive, and appropriate whatever happened to fit. I [sic] took one shirt, one pair of trousers, and one under-waistcoat, which was all I required. Shoes and stockings being luxuries, I did not meddle with them. I should have mentioned that a few days ago Carleton commenced teaching the whole of the adults upon the island to sing, at which they were highly delighted. At 8 P.M. Carleton gave an extra singing-lesson in our new house, which ended in a house-warming. Edward Quintal brought his fiddle; he had picked up some hornpipe and reel tunes by ear on board ship, which he really played with great spirit, and the true artistic twang, not omitting the stamp and wriggle, or the grind upon the fourth string. Some of the islanders danced very well, not waltzes certainly, but reels. The women never dance. We three, Carleton, Taylor, and myself, danced a Scotch reel, which threw the spectators into ecstasies. The women shrieked with laughing. We ended with blind-man's-buff and many other innocent games, in which the ladies joined: there was every sort of sky-larking possible. April 2nd. At two o'clock in the morning we sent the whole island home – certainly not to sleep. Fine clear weather, with moderate south-east wind. During the |

morning I employed myself in making some walking canes from the cocoa-nut and palm trees; in the afternoon I went down to the rocks, and helped the men and women to carry up some planks, which were being landed in their boat from another part of the island. Dined with Arthur Quintal, senior; attended the school and received a copy-book containing the writing of many of the scholars, which I had specially requested. April 3rd. Fine weather, with light north-east wind. Collected much information from A. Quintal, senior, which will appear verbatim in my description of the island. April 4th. Fine, north-east wind. Employed all day collecting shells, but not with much success. April 5th. Wind south-east, and fine. Employed myself in collecting shells; took a good look ont from the highest part of the island, thinking to see a vessel. April 6th. North-west wind, and fine. Made some walking canes, and attended the musical class. April 7th. North-west wind, and fine. Went twice to church. April 8th. North-east wind, and fine. Finding so much to do in collecting information regarding the island, I was compelled to leave off attending the musical class. Cleaned up all my shells excepting a duplicate set. April 9th. Wind south-east, and fine. After breakfast, about fifty of the islanders went round to the west side of the island in their three whale boats, and some in canoes, to bring in a store of cocoa-nuts. I joined |

them, and a very pleasant day I spent. I was much disappointed at not finding any new specimens of shells, as it was by far the warmest side of the island. Cocoa-nut on the west side of the island are very abundant, and appear to do much better there, on account of the warmth. In cultivating this tree, nuts which are perfectly dry and ripe are chosen, and put into a piece of ground by themselves. As soon as they begin to shoot, they are taken up and planted where they are intended to remain. This plan is adopted in consequence of many of the nuts failing to germinate; they generally take eight years before they bear; a good tree in full bearing will produce from 100 to 300 nuts annually. In the course of conversation with some of the girls, whilst feasting upon cocoa-nuts, I spoke to them about their beauty; when one of them observed she did not think I was an Englishman. I asked with some curiosity what could have led her to such a conclusion, and was informed by the fair damsel in question, that I flattered too much to be British born. I was not a little surprised at the anawer I received. April 10th. Strong south-east wind, and fine. At daylight a vessel was observed, which created a great commotion on the island, more especially among the women, who thought there was some chance of their losing their singing-master (Carleton); many of them were in tears, and many more in very low spirits. At 10 A.M. I went over to the south side of the island with Mr. Nobbs, who took a spy-glass with him; but it was some time before we could make her out, as she was |

about ten miles to the southward of the island. After remaining about an hour we returned. At 1 P.M. she came in sight of the settlement. I took another look at her through the glass, and found her to be an American whale ship, but no chance of her being near enough to board until the morrow. When the islanders heard me say she was a whale ship, and not an English merchantman, as many of us thought, from her coming from the southward, the delight that appeared in the whole of their countenances was most gratifying to us. In fact, they had begun to look upon us, not as strangers who had been left upon the island, but as of themselves. April11th. Strong south-east wind. At 8 A.M. the captain of the American ship came on shore. She proved to be the George and Susan, of New Bedford, Captain White, eleven days from Tahiti, and bound on the middle ground. He expressed great commiseration for our mischance, and said that had he been bound to the Sandwich Islands or Tahiti he would willingly have taken us on; but as he was away for his whaling ground he could not offer us any assistance. He gave us some Californian news, and among other things happened to mention, in the hearing of some of the islanders, that lime juice was worth sixty dollars a barrel. The islanders immediately set to work with the intention of filling a few barrels for us, that we might not be entirely unprovided for in case we should arrive at San Francisco before the Noble, which it must be confessed would be placing us in a most awkward predicament. Our intention is to indulge them with the satisfaction of |

giving it to us, to take it on, and remit the proceeds to the donors. At noon, the church bell was loudly rung. I ran to learn the occasion, and found that a barque with English colours flying was close to the island. This really created a very great sensation, as there could be but little doubt of the stranger being bound for California, from the number of people that appeared to be on board. The poor women, if it were possible, looked far more melancholy than they did when the former vessel was reported in sight; but as to ourselves we were too gladly anticipating the chance of getting off the island, to follow out the intentions and pursuits which we had originally planned in New Zealand. But at the same time I must say that I shall much regret when I do leave, on account of the great kindness I have received from every one on the island. Their kindness and real hospitality have been unbounded, and I firmly believe that I often hurt their feelings by not accepting everything that they offered me. At 3 P.M. seven of the islanders went off to the English barque in their whale boat, and I accompanied them. At 4 P.M. we boarded her, when she proved to be the barque Colonist, from Adelaide via Auckland, Captain J. Marshall, with 120 passengers, three months out, and short of provisions. After remaining on board for some time, I informed the captain of our unfortunate (although in one sense of the word fortunate) situation, and begged very hard to obtain a passage from him, which he said was quite out of the question, on accorte of the crowded state of his vessel. Putting all things togetber, I really thought that his answer would have |

been mine, had I been placed in the situation that he was; but, however, being a married man I thought it was my duty to try to the last, which I did, and was again refused. The want of water and provisions appeared to be the great stumbling-block to any of us getting a passage in the barque. I therefore offered to get the islanders off to the vessel the next morning early, to water the vessel and procure whatever provisions could be spared. About 5 P.M. I left the vessel, along with the seven natives, in the whale boat, anticipating a more fortunate result in the morning. Upon landing, I was assailed by a storm of questions as to our chances of getting away, which I was unable to answer, for I did not know what they were myself. In the evening while talking to Carleton about the vessel I mentioned the captain's name; he immediately recognised him as an old acquaintance, having once chartered his former vessel (the Haidè, since lost in the Bay of Honduras), for the purpose of bringing cattle from Sydney to New Zealand. This I looked upon as rather a lucky coincidence, and that Carleton and myself had a better chance of now getting away than we had before. During the evening, I packed up every thing that I had upon the island, which certainly was not much, so that I might at all events be ready. April 12th. At 8 A.M. we went off in one of the island whale boats. As soon as Carleton got on board the Colonist, he went up to Captain Marshall and shook bands with him. Captain M. at first did not recognise him; but very soon did, and, as may be supposed, was much |

surprised to find his old acquaintance upon such an out of the way island. After breakfast we both asked Captain Marshall if he could not make room for us, as neither of us was a Daniel Lambert, nor were we encumbered with much baggage. He again told us that he had no room, and that his people were on short allowance already. The islanders then asked us if we were ready to go on shore with them, as they were ready to go. Carleton looked at me and I looked at him. I was impelled to petition the captain once more to make room for us, when he again denied us; but with some little hesitation, which I took advantage of, and offered to put provisions on board for ourselves, if he would only make room for us. He looked down the hatchway of the fore cabin and said – "If you can manage to sleep there, you may go," pointing to the lockers where we were to sleep. We both thanked him, and most willingly accepted the kind offer. We then returned on shore, taking with us a Mr Carwardine, one of our intended messmates, whom we looked upon in the light of a hostage, insuring us against the departure of the vessel while we should be making our adieus. Many of our kind and dear friends met us upon our landing, seemingly afraid to ask what success we had met with. Our boat's crew relieved us from the unpleasant task of communicating the news ourselves. It will be some time before I forget the pretty faces of some of the women, their cheeks covered with tears when they were made aware of our intention of leaving them, which they said was very unkind upon our part; I told them it was our duty to |

take the first opportunity which presented itself; but that we should never cease to bear them in mind. One of the boat's crew had heard me speak to the captain about bringing some provisions on board for our own use, which he mentioned forthwith to those on shore. One and all set to work without delay, and collected for us as much as filled a large whale boat, pigs, goats, ducks, fowls, pines, oranges, lemons, bananas, plantains, and cocoa nuts, along with two large sacks of sweet potatoes and yams. Owing to the almost immediate arrival of the Colonist, the islanders were unable to execute their provident intention with regard to the lime juice, and we shall lose the pleasure of surprising them in the manner we had anticipated. After taking leave of my worthy host, Mr. Nobbs, and also of Mr. Buffett, who did not accompany us to the landing-place, we all, I may say the whole population, proceeded to the place of embarkation. Before leaving, Mr. Nobbs paid us both a very high compliment relative to our moral and sedate behaviour while resident upon the island; indeed we had both of us made a point of never being out after dark, to obviate ail chance of remarka being made, and which the natives had not been slow to observe. I may here mention a matter in which the islanders take the greatest interest, of which I have made hitherto but little mention, purposely that I might wait the issue of the experiment. As might be supposed, our great anxiety was to make some little return for the warm hospitality with which we were treated; a wish however which it was not so easy to |

gratify, seeing that our sole possessions, when we found ourselves left on shore, consisted of the clothes we wore and a tuning-fork which happened to be in the baron's pocket. It luckily occurred to my friend Carleton, who had observed their imperfect attempt at psalmody in church, that a little musical instruction might prove a great amusement to them. Our worthy friends caught at the proposai with eagerness; and on the very same day all the needful apparatus – a ruled board, conductors, baton, &c., – were prepared, and the first lesson was given to the whole adult population, in a new house as yet unoccupied. They proved remarkably intelligent, not one among the number being deficient in ear, while many had exceedingly fine voices. The progress surpassed the most sanguine expectation of the teacher; on the fourth day from the commencement, they sang through a catch in four parts, with great steadiness; for people who had been hitherto unaware even of the existence in nature of harmony, the performance was very remarkable. Both pupils and preceptor appeared to take equal delight in the task; and we heard them, after a fortnight's instruction, singing among themselves in the open air trios and quartettos, for the most part performed in chorus, during the greater part of the night. They have among them some books of instruction in this delightful art, and are now sufficiently advanced to be able to pursue the study without assistance. It is very gratifying to leave behind us some little memorial of our residence, even though it be of so airy a nature as this; abiding our time to requite so much kindness with tokens of a |

more substantial nature. Our situation upon the island was certainly, in a manner of speaking, an unfortunate one; but nevertheless a happy period in our lives, and to have given cause for offense would have been a most foul breach of hospitality. May every one who enjoys the pleasure of a few days' sojourn on the island, be looked upon on leaving with the same respect as we ourselves! I am now going to make what may be perhaps considered a strong assertion, which is, that there never was, and perhaps never will be, another community who can boast of so high a toue of morality, or more firmly rooted religions feelings, than our worthy and true friends the Pitcairn islanders. To have witnessed such a state of things is a blessing that few men and fewer women have ever been privileged to enjoy upon God's earth. The only islanders that I ever saw that at all approached them in one of these respects, is the island of Mauke, one of the Hervy Islands, which I visited in 1842, on my way from Tahiti to New Zealand; an island about four times as large as Pitcairn's, with a population of about 400. They were brought up and taught under a native teacher from Tahiti, some forty years ago, who was taken there by the late Rev. John Williams and the Rev. Mr. Barff, of Hauhine, one of the Society Islands. On this island there were one or two strange women from some of the neighbouring islands, who had committed themselves; but upon Pitcairn's such a transgression was never known since old John Adams's time. A scene followed our arrival at the landing-place, while the boat was being loaded, that I shall never forget. |

The poor girls clung round us as we stood upon the beach; but more especially did they cling round my friend Carleton, who had taken so much trouble in teaching them to sing; many of them with the handkerchiefs thrown over their heads, and all of them in floods of tears. We tried to put a bold face upon the matter, but had much ado to maintain that decorous impassibility which is required of men with beards upon their chins. Carleton tried to get up a chorus; but it broke down, and only made matters worse. This scene lasted for about an hour. One of the passengers of the Colonist (Mr. Carwardine), who was not in the secret, looked on in mute astonishment; and I am sure that Carleton, as well as myself, felt glad when the signal for embarkation was made by the boatmen. Things having gone so far, we thought we might make a handsome finale to our sojourn upon the island. We first took our worthy hostesses, who were rather ancient matrons, and gave them what was probably the heartiest kiss they had received these many years. The ice once broken, there was no affectation of mock modesty, we went to all in turn, and gave and took in right good earnest: the contrast here was great, as we had hitherto behaved with the most marked reserve; but we parted with the same feelings as if we had been members of the same family. And thus ends my brief stay among the most simple, innocent, and affectionate people it was ever my lot to be thrown amongst. There is a charm in perfect innocence which he must be indeed hackneyed and har- |

dened who cannot feel. Such a society, so free, not only from vice, but even from those petty bickerings and jealousies – those minor infirmities which we are accustomed to suppose are ingrained in human nature – can probably not be paralleled elsewhere. It is the realisation of Arcadia, or what we had been accustomed to suppose had existence only in poetic imagination, – the golden age; all living as one family, a commonwealth of brothers and sisters, which, indeed, by ties of relationship they actually are; the earth yielding abundantly, requiring only so mach labour as suffices to support its occupants, and save them from the listlessness of inactivity: there is neither wealth nor want, a primitive simplicity of life and manner, perfect equality in rank and station, and perfect content. They have happily been preserved from establishing a community of property, which would indeed be a complete bar to civilisation. Add to this, that their practical morality and strong sense of religion promise a lasting continuance of the blessings they enjoy, together with another pleasurable emotion – warm loyalty to their queen and attachment to the mother country; their only anxiety being the smallness of their island. At sunset we got on board the barque Colonist, when we found that some of the passengers had just gone on shore, and would not be on board again until morning, so I made myself as comfortable for the night as circumstances would admit of. April 13th. Shortly alter breakfast, two whale boats came off with the passengers, and one of the islanders |

brought Carleton and myself a letter each. The following are copies: –

"To Mr. H. Carleton, Esq.

"Pitcairn's Island, April 12th, 1850.

"Kind Preceptor, "When you parted from us last evening, little did we then think that we should be so nigh to you another day, or that we should be able to address you. It would have given us much pleasure to have seen you on shore; but as that may never be, we are glad to have an opportunity of sending you our last and fondest adieux. Wherever you go, our prayers and best wishes will follow you; and, till time lasts, we shall ever think of our beloved preceptor. "From your loving pupils,

|

"To Mr. Walter Brodie.

"Pitcairn's Island, April 12th, 1850.

"Kind Friend,

"Little did we think, when parting from you yesterday, that we should be able to address you again to-day. It would have given us great pleasure to have seen you; but as that may never be, we now embrace this opportunity of sending you our last adieus. We will long think of you; and, wherever you go, our kind wishes will follow you. Remember us to all your friends, and think of us wherever you go. "Yours most truly,

(Signed) "Rebecca Christian. "Sarah Quintal." At 4 P.M. the two whale boats left the barque Colonist for the island; and, when a few yards off from the vessel, they gave us three hearty cheers, which were answered by all on board in the most deafening manner. At 5 P.M. sailed for San Francisco. |

Crew of H. M. Ship Bounty, who landed at Pitcairn's

Island, December, 1789.

The present inhabitants of this island are the descendants of Christian, Young, Quintal, M'Coy, Mills, and Adams; together with three Europeans, Nobbs, Buffett, and Evans, who have been allowed to remain upon the island for upwards of twenty-five years. Brown, Martin, and Williams had no issue; neither had any of the Tahitian men. Fletcher Christian married Isabella, a Tahitian woman. Issue; Thursday October, Charles, and Mary. Thursday October married Susanah, widow of Edward Young. Issue; Charles, Joseph, Thursday October, Mary, Polly, and Peggy. Charles second, married Maria Christian. Issue; Rebecca, Charles. Joseph, not married. |

Thursday October married Mary Young. Issue; Albert, Elias, Alfonzo, Julia, Agnes, and Rose Anne. Mary, not married. Polly married Edward Young. Peggy married Daniel McCoy; and secondly, Fletcher Christian. Charles first, son of Fletcher Christian of the Bounty, married Sally, a Tahitian child, that came to the island when an infant, in the Bounty. Issue; Fletcher, Edward, Charles, Isaac, Sarah, Maria, Mary, and Margaret. Fletcher married Peggy Christian, widow of Daniel M'Coy. Issue; Jacob, Stephen, Nathan, William, Priscilla, Polly, Lucy, Emily, and Abigal. Edward died unmarried. Charles married Charlotte Quintal. Issue; Andrew, Gilbert, Kitty, Adeline, Ellena, Cordelia, and Lucy Anne. Isaac married Mirriam Young. Issue; Henry, Godfrey, and Emiline. Sarah married George Nobbs. Maria married, first, Charles Christian; secondly, John Quintal; and thirdly, William Quintal. Mary married Arthur Quintal, senior. Margaret married Matthew M'Coy. Mary, daughter of Fletcher Christian of the Bounty, never married. Edward Young married Susannah, a Tahitian woman. Issue; none; but had a family by two Tahitian women during the time he was married to Susannah, one of which was Fletcher Christian's widow, the other was the wife of one of the Tahitian men. Issue by the former |

of these two, Edward, Polly, and Dorothea; by the latter, Nancy, George, Robert, and William. Edward married Polly Christian. Issue; Moses. Polly married George Adams. Dorothea married John Buffett. George married Hannah Adams. Issue; Frederick, Simon, Dinah, Betsy, Jemima, and Martha. Robert died unmarried. William married widow of Matthew Quintal second. Issue; Mayhew, Mary, Mirriam, Dorcas and Lydia (twins). Moses married Albina M'Coy. Issue; Mary Elizabeth. Frederick married Mary Evans. Issue; none. Simon married Mary Buffett. Issue; Lorenzo, Robert, and Eliza. Dinah married John Quintal second. Betsy married John Buffett second. Jemima and Martha, not married. ––– Brown married a Tahitian woman, but had no issue. John Mills married a Tahitian woman Issue; Elizabeth, who married Matthew Quintal. William M'coy married a Tahitian woman Issue; Daniel and Kate. Daniel married Sarah Quintal. Issue; William, Daniel second, Hugh, Matthew, Daniel third, Jane, Sarah, and Albina. Kate married Arthur Quintal first. |

William died unmarried. Daniel married Peggy Christian. Issue; Philip. Hugh died unmarried. Matthew married Margaret Christian. Issue; Russel, Jane, Diana, Mary, Harriott, Sarah, and Sophia. Daniel third, married Lydia Young. Jane and Sarah died unmarried. Albina married Moses Young. Isaac Martin married a Tahitian woman, but had no issue. John Williams married a Tahitian woman, but died without issue. Matthew Quintal married a Tahitian woman. Issue; Matthew second, Arthur, Sarah, Jane; he also had a child by Susannah, the wife of Edward Young of the Bounty, Edward. Matthew married Elizabeth Mills. Issue; John and Matthew third. Arthur married first, Kate M'Coy; secondly, Mary Christian. Issue by the first wife; Arthur, Kitty, John, Charlotte, Phoebe, James, Caroline, and Ruth: issue by the second wife; Absolem, Nathaniel, Joseph, Cornelius, and Mary. Sarah married Daniel M'Coy first. Jane went to the island of Rurutu, in the brig Lovely Ann. Edward married Dinah Adams. Issue; William first, |

Edward second, Abraham, Henry, Caleb, Martha, Louisa, Nancy, and Susan. John Quintal, son of Matthew second, married Maria, widow of Charles Christian second. Issue; Eliza, Sarah, Ellen, and Maria. Matthew Quintal unmarried. Arthur second, married Martha Quintal. Issue; Edward, Edmund, Victoria, Rhoda, and Rachael. Kitty died unmarried at Tahiti. John married Dinah Young. Issue; John, William, Augusta, Matilda, and Kesiah. Charlotte married Charles Christian third. Phoebe married Josiah Adams James unmarried. Caroline married John Adams second. Ruth, Absolem, Nathaniel, Joseph, Cornelius, and Mary, unmarried. William Quintal, first, married Maria, widow of Charles Christian; secondly, married widow of John Quintal. Issue by the first wife, John, Oliver, Edward, Abbey, and Helen. Edward second, unmarried. Abraham married Esther Nobbs; no issue. Henry and Caleb, unmarried. Martha married Arthur Quintal second. Louisa, Nancy, and Susan, unmarried. John Adams first married a Tahitian woman, the widow of John Mills. Issue; Dinah, Rachael, and Hannah. Secondly, the widow of William M'Coy of the Bounty. Issue; George. |

Dinah married Edward Quintal first. Rachael married John Evans first. Hannah married George Young. George married, first, Polly Young. Issue; John, Jonathan, and Josiah; married, secondly, widow of Daniel M'Coy. No issue. John married Caroline Quintal. Issue; Gilbert, Byron, George, and Polly. Jonathan married Phoebe Quintal. Issue; Calvin and Eliza. Josiah unmarried. George Nobbs married Sarah Christian. Issue; Reuben, Esther, Fletcher, Francis, Jane, Naomi, James, Edwin, Jemima, and Sydney. Esther married Abraham Quintal; all the rest are single. John Buffett married Dorothy Young. Issue; Thomas, John, David, Robert, Benjamin, Edward, and Mary. Thomas, unmarried. John married Betsy Young. Issue; Henry and Eveline. David, Robert, Benjamin, and Edward, unmarried. Mary married Simon Young. John Evans married Rachael Adams. Issue; John, William, George, Mary, Dinah, and Martha. John, William, George, Dinah, and Martha, unmarried. Mary married Frederick Young. |

LIST OF CARLETON'S MUSICAL CLASS.

|

|

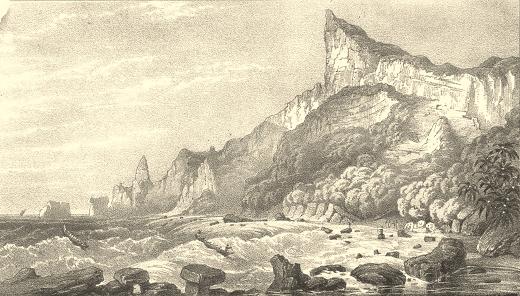

Landing in Bounty Bay. |

PITCAIRN'S ISLAND,Now memorable for having afforded refuge to the mutineers of H.M.S. Bounty, was discovered by Cartaret. It is about one mile and a half long, and four and a half in circumference. The true latitude and longitude, incorrectly laid down in many charts, is 25° 0' 4" south, and 130° 0' 8" west. It it[sic] rises abruptly from the sea, and is iron bound. It was taken possession of, November 29th, 1838, by Captain Elliott of H.M.S. Fly, for the crown of Great Britain. On nearing the island, vessels should make the north-east end, St. Paul's Point,* off which run a few large rocks, all above water; the largest of these is a square basaltic islet, and inshore are several high pointed rocks, which the pious islanders have named after the most zealous of the apostles, about fifty feet above the water, with room for a boat to go between them and the mainland. About a quarter of a mile to the westward, is a small boat harbour, the only landing-place which a stranger would find without the assistance of an islander, the surf appearing to break heavily all round the northern end of the island. The Bounty's crew pulled twice round the island, before they hit upon it. There is very good anchorage, when * The highest point of land in the accompanying print in Bounty Bay |

there is any easting in the wind, for vessels of any size, to the westward of the island, about a quarter of a mile to the southward of the north-west end of the island, off which lie a few large rocks above water, similar to those off the north-east end, the depth of water being from eight to twenty-five fathoms from a quarter to three quarters of a mile off shore. There are neither shoals nor sunken rocks off the island, over a quarter of a mile off shore. For the last fifteen years the regular trade-winds have ceased to blow; but, seven months out of the twelve, the winds are from south-east to east (from September to March inclusive). In the bight of the first little bay, after rounding the north-east end of the island, and about a quarter of a mile to the westward of the same, you will observe a small clump of cocoa-nut trees (six in number), very near the water's edge, on the right hand, and one single cocoa-nut tree on the left, about two hundred yards from the six trees on your right, with a large grove of cocoa-nut trees above on the hill, a little to the westward. When near the shore, three boat-houses may be observed, containing as many whale boats and several canoes. The landing-place is just below the boat-houses, and between the clump of one and six cocoa-nut trees – a shingly beach, only of sufficient breadth to allow of two boats abreast to land at one time. Care must be taken to observe the rollers, which are very irregular in coming in, and the channel in is winding between the rocks. These rocks are only a few yards from the shore, and the distance between them very narrow. When a stranger |

comes in, a native generally takes his station upon a rock on shore, and waves his hat, to indicate a favourable opportunity for pushing ahead; but strange boats seldom come on shore before some of the natives go on board them. A stranger, in a square-sterned boat, might meet with an accident; but, at the worst, a sound ducking would be the only consequence. To any person acquainted with the locality, I consider the landing as perfectly safe. Having set foot on shore, you ascend a steep hill, almost a cliff, for about three hundred yards, to a table land, planted with cocoa-nut trees, which is called the Market-place; about a quarter of a mile beyond which, at the north end of the island, lies the settlement, flanked by a grove of cocoa-nut trees, kumeras, and plantains, &c., &c., which makes the approach very picturesque. The island is evidently of volcanic origin. The highest point (Look-out ridge) is about 1008 feet above the sea. Scoriae are scattered about, but not to an extent to interfere with cultivation. The soil generally is of a deep red, apparently decomposed lava, and very productive. The island rat, which is rather small, and the lizard, are the only quadrupeds indigenous to the island. Only one land bird is known to breed upon the island – a small species of fly-catcher, of a dirty white and brown colour, and three sea-birds – a white skiff (which is referred to in the laws), a brown skiff, and the man-of-war bird or hawk, all of which the islanders eat. They have three whale boats: two of them were presented by the English Government, the other was |

purchased from a whaler. Their canoes, about twenty in number, hold generally two persons, and are so light that one man can carry them. They can be made to last five years, by being constantly painted; but the tree from which they are made, is getting very scarce. The culinary vegetables are kumeras, potatoes (Irish and sweet), yams, pumpkins, and two sorts of beans which they keep and dry for many months. Cabbages and onions are rather scarce. Herbs they have none. Their fruits are pines, four species of plantains, and bananas, oranges, limes melons, paw-paw apple – a fruit somewhat resembling a small English apple, and cocoa-nuts. St. Pierre, in his book upon the works of nature, mentions that he never heard of any accident occurring from the fall of a cocoa-nut from off the tree during his lifetime, or even ever read of such a thing; but one of these rare – I may say very rare – occurrences happened here lately, and nearly killed Mrs. Nobbs. The indigenous Flora of the island is not rich, but many valuable trees and plants have been imported from Tahiti. Of land shells there are only three species, and those very minute. Of sea shells I collected about forty species; but many more are probably to be found, as I was only able to search a part of two sides of the island, having been obliged to take advantage of the arrival of the barque Colonist, before completing my exploration. There are but few insects to be seen; but at certain times the caterpillars are very destructive, making their appearance in large swarms. There are but four head of cattle upon the island. H.M.S. Daphne |

Captain Fanshaw, in August 1849, landed a bull and cow from Valparaiso: the cow has since calved; but the bull was unfortunately killed, as mentioned in my diary. Two heifers and a young buil were sent by some gentlemen from New Zealand as a present; but, on account of the tedious voyage, the captain of the vessel in which they were shipped, found it necessary to kill one, that fodder enough might be left for the other two. Owing to contrary winds, he was obliged to run into Tahiti, where the cattle were reshipped on board an American whaler, the master of which very kindly gave them a passage to their destination. I observed many goats running wild, and about a score of rabbits around the houses, which were brought by H.M.S. Daphne in 1849. Fowls are very numerous. Pigs scarce. Cats numerous, and wild in the bush, and are encouraged to kill the rats, although they probably destroy more fowls than rats. There are many dogs, useless animals enough, and very currish in appearance. There is no doubt but that this island was formerly inhabited, although the native race must have been extinct many years prior to the arrival of the Bounty. Burial-places are still to be seen, and large, flat, hewn stones, in different parts of the island, which must have been for pavement in front of their houses, such as are still in use among other tribes in the South Seas. These stones, when observed by the crew of the Bounty, had very large trees growing up among them, by which in many places they had been displaced. Stone images were likewise found, supposed to have been objecta of |

worship; they were made of a hardish coarse red atone. Stone spearheads and small axes are very common; and round stone balls, of about two pounds' weight, some of which are generally found when working up new ground, all of which are made of a bluish black atone, very fine grained and smooth. The spots where the images and stoneware were made, may be recognised by the large accumulation of chips in varions parts of the island. Human bones have been repeatedly found, although not during the last eight years; and, in one instance, a perfect akeleton was discovered, in the last state of decay, with a large pearl shell, of a sort not belonging to the island, under the skull. This is a custom with the natives of the Gambier Islands, Bow Island, High Island, Toubouai, and nearly all the Pumutu or Low Islands. The cocoa-nut trees, bananas, plantains, and breadfruit trees, as well as the yams and sweet potatoes, found here by the crew of the Bounty, are an additional sign of the previous occupation of the island, more especially as they were confined to one single spot. It is very unlikely that these plants should have been indigenous so far to the southward, as they will not grow upon every part of the island, but merely upon a few of the warmest spots or situations on the lower ridges. These aborigines were most probably drifted here upon a raft, it having been a custom, many years ago, especially at the Gambier Islands, which are to the W.N.W., about three hundred miles from Pitcairn'a Island, and of many of the Low Islands, to put those who were vanquished in war upon rafts, when the wind was off |

the land, sending them adrift to whatever place they could fetch. Two actual instances of this practice were mentioned to me by Mr. Nobbs; one came under his cognisance while he himself was at the Gambier group. There is an island, about sixty miles to the E.S.E. of Gambier Island, called Crescent Island, to which Mr. Nobbs and Captain Abriel, in the American schooner Olivia, and Captain Cornish, in the Olive Branch, paid a visit in 1836, having heard that pearl-shell was to be found there in great abondance. On landing, they were much surprised at finding about forty natives living upon it, although unknown to the natives of the Gambier Islands. There being a few of the Gambier islanders on board of the Olive Branch, the party was enabled to communicate with these people, who told them that their prior generation, who were then ail dead, had been put upon a raft and sent to sea, having been worsted in a battle at the Gambier Islands; and that after drifting upon the ocean for several days, they were cast on shore where they were now found. After remaining upon the island for two days, Mr. Nobbs's party returned to the Gambier Islands, taking with them a few of the Crescent islanders. On their arrival at the Gambier group, the natives of that group, hearing of the strangers, a great meeting was held, when it was ascertained that the account which had been rendered was perfectly correct. The next day some of the Gambier group chiefs hired Captain Abriel's launch, giving him in payment four tons of Too (Breadfruit put under ground, after being cut up and left there to ferment). This was much re- |

quired by Captain Abriel, who had a party of natives fishing for pearl shells, as food for his divers. The launch started, and in a few days returned again with all the Crescent islanders on board. Upon their landing, the Gambier islanders gave them a grand feast, of which the guests partook so plentifully, that some of them actually died from repletion. In the other instance mentioned by Mr. Nobbs, the beaten party, likewise from the Gambier Islands, reached an inhabited island, called Rapa or Opazo, about 700 miles S.S.E. of Tahiti, or 600 miles S.W. from the Gambier Islands. The last of these refugees died about six years ago. Very little information is at present to be gathered upon the island, concerning the famous mutiny of the Bounty. Beyond a few stray anecdotes of no great interest little remains. But the account given by the islanders, such as it is, differs materially from that published by Captain Bligh, after his return to England. They flatly deny his assertion, that the original cause of the mutiny was the connexion formed by the crew, while at Tahiti, with the Tahitian women; attributing it entirely to his own perverse temper and tyrannical conduct. His language, particularly to his officers, is stated to have been habitually and inexcusably coarse. Of this a single example will suffice, which I give in the words of the narrator. "Some fruit, which had been sent on board for the captain's cabin, having been left upon the quarter-deck, disappeared; Captain Bligh was exceedingly angry, and in rating Christian about the matter, made use of this expression, 'I suppose you |

have eaten it yourself, you hungry hound!'" Can we be surprised at insults of this nature rankling in the mind of a susceptible man, and driving him at last to the desperate deed by which he secured himself against their continuance? After the mutineers put Captain Bligh out of the Bounty into his boat, along with seventeen of his crew, the mutineers made sail for the Island of Toubouai, which is about 500 miles south of Tahiti, where they agreed to remain and establish themselves, provided the natives, who were numerous, were not hostile to their purpose. Of this they had very early intimation, an attack being made upon a boat which they sent to sound the harbour. They however effected their purpose, and the next morning the Bounty was warped inside the reef that formed the port, and stationed close to the beach. An attempt was made to land, but the natives disputed every foot of ground with spears, clubs, and stones. After two days they returned to Tahiti, and were received with the greatest kindness by their former friends. After some time they again returned to Toubouai, but were again obliged to go back to Tahiti, finding the natives there opposed to their settling among them. After landing, Haywood and fifteen others of their party were taken by H.M. frigate Pandora, which was sent out in search of them as soon as Bligh returned to England, and which vessel was wrecked in Torres Straits, on her way to England. Christian and eight others then sailed for Pitcairn's Island, after securing for themselves each a wife, as well as six Tahitian men and three women, wives of |

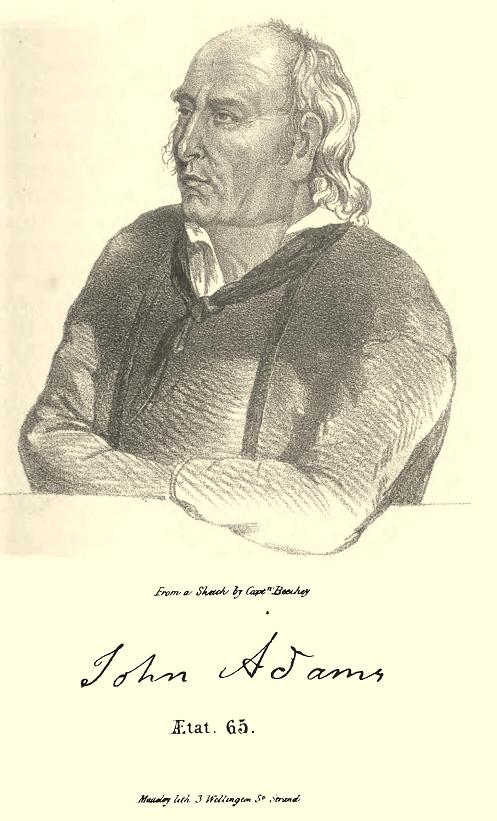

three of these six men, Christian keeping his own counsel as to their destination. He resolved upon Pitcairn's Island, induced by Cartaret's discription, which had chanced to be on board the Bounty. Although many notices of the mutineers and their descendants have at different times been given to the world, I do not recollect to have seen any connected history of so interesting a community; for the simple reason, that no one has ever remained on the island long enough to obtain it, previous to my stay there. Its early records are sad indeed. The crimes of the original settlers were heavily visited upon them, as will appear by the following account, taken down verbatim – even to the grammatical errors – from the recital of Arthur Quintal, senior, who, with George Adams and five women, are all that remain of the first generation: – "When the Bounty came here, there were nine Englishmen, six Tahiti men, twelve Tahiti women, and a little girl, landed. The Englishmen had each a Tahitian women for a wife, and three of the Tahitian men were married to the remaining three women. Some time afterwards Williams's wife died of sickness. The Englishmen then combined together, and took one of the Tahitians' wives for another wife for Williams. This created the first disturbance between the English and the Tahitians. William Brown was sent out by the English Government in the Bounty, as gardener, to look out after the breadfruit plants, which the said vessel was to convey to the West Indies. Brown and Christian were very intimate, and their two wives overheard, one |

night, Williams's second wife sing a song, – 'Why should the Tahitian men sharpen their axes to cut off the Englishmen's heads?' Brown and Christian's wives told their husbands what Williams's second wife had been singing. When Christian heard of it, he went by himself with his gun to the house where all the Tahitian men were assembled. He pointed his gun at them, but it missed fire. Two of the natives ran away into the bush – one of them to the west part of the island, the other to the south end of the island. The Tahitian (Talalo) who went to the west side, was the husband of Williams's second wife. One day Talalo saw his wife, and the wives of the other Tahitian men, fishing; he beckoned to her, and she went to him. He then took her away into the bush. Another Tahitian, named Temua, then joined Talalo and his wife in the bush. After this, Christian and the other Englishmen sent a Tahitian (Manale) in search of them; he was not long away before he found them, and then returned and told the Englishmen of it. The Englishmen then consulted among themselves what to do, when they agreed to make three puddings and send them. One pudding, having poison in it, was to be given to Talalo, and the other two were to be given to the wife of Talalo and the Tahitian (Temua) who had joined them. The puddings were sent by the native, Manale, who gave them to the three natives individually; but a suspicion coming across Talalo's mind that his pudding had poison in it, he would not eat it, but eat his wife's pudding along with her. When Manale found that Talalo would not eat his pudding, he induced the |

three to go up into the bush a little way, where he told them he had left his wife among some breadfruit treea. As they went up to see Manale's wife, the foot-path being very narrow, they walked behind each other, Manale being behind and next to Talalo. Manale, having a pistol with him, and having instructions to kill Talalo before he returned, now took the opportunity, and pulled the trigger of his pistol, it being pointed at Talalo's head; but it misfired. Talalo, having heard the noise occasioned by the trigger being pulled, turned round, and saw the pistol in Manale's hand. Talalo then ran away and Manale after him; they then had a severe struggle, when Talalo called to his wife to help him kill Manale, and Manale told the woman she must help him kill her husband, which she did; and in a very short time Manale and Talalo's wife killed Talalo. Manale, the woman, and the other native (Temua), then returned to the European settlement. Williams then took the woman again for his second wife, as he had formerly done. Christian and the other Englishmen then sent Manale to find the other Tahitian (Ohuhu), who had gone to the south side of the island, whom he also soon found, and then reported his success to the Englishmen. The English then sent Manale and another Tahitian (Temua) to kill him, which they succeded in doing, while pretending to cry over him. They then returned home again to the Europeans. The whole of the Bounty people then lived together for some time (about ten years) in perfect harmony. The six Tahitian men from the Bounty were brought down as servants to M'Coy, |

Mills, Brown, and Quintal. This island, when these people came here, was completly covered with sea-birds, and when they arose, they completely darkened the air. These remaining four natives were employed to work in collecting a lot of these birds for their masters' food, after they had done their work in their masters' gardens; they also fed their pigs which they brought from Tahiti on these sea-birds. Whenever the Tahitians did any thing amiss, they used to be beaten by their masters, and their wounds covered with salt, as an extra punishment. The consequence was, that two of these Tahitians, Temua and Nehou, took to the bush, and with them each a musket and ammunition, with which they used to practise firing at a target in the bush. Edward Young had a garden some little distance from the settlement; and the two natives which took to the bush, used at times to come and work for him, as well as the other two natives, who lived in the settlement. Young appeared to be very friendly with the Tahitians; and John Adams mentioned that he had every reason for supposing that Young had instigated the natives to destroy the Englishmen, excepting himself (John Adams), Young wishing to keep Adams as a sort of companion. At planting time, each Englishman had his own garden, which were some distance apart from each other, being in separate valleys, on the north end of the island. Three of the Tahitians, finding that the whole of the Englishmen were widely scattered and unprotected, commenced to destroy them, beginning with John Williams and Fletcher Christian. At the time they |

shot Christian, Christian hallooed out. Mills, M'Coy, and Manale, were then working about 200 yards from Christian's garden, and M'Coy hearing Christian call out, Oh dear!' told Mills he thought it the cry of a wounded man; but Mils thought it was Christian's wife calling him to dinner. After the three Tahitians had killed Christian, they then went to where Mills was working, and one of them (the other two being concealed in the bush) called to Mills, and asked him to let his native, Manale, go along with them to fetch home a large pig they had just killed. Mills then told Manale that he might go. Manale then joined the three Tahitians, when they told Manale that they had killed Williams and Christian, and wanted to know how they might destroy Mills and M'Coy. It was at last agreed that these three men should creep into M'Coy's house, unobserved; which they succeeded in doing. Manale then ran and told M'Coy that the two natives that had taken to the bush were robbing his house. M'Coy then ran to his house, and as soon as he got to the door, these three natives fired upon him, but did not kill him. Manale, seeing that they had not killed him, seized him; but M'Coy, being the strongest of the two, threw him into the pig sty, and then ran and told Mills to run into the bush, as the natives were trying to kill all the white men. But Mils would not believe that his friend Manale would kill him. M'Coy then ran to tell Christian, but found that he had been murdered already. About this time, M`Coy heard the report of a gun, which he supposed had killed Mills, and |

which turned out to be the case. M'Coy then ran to Christian's wife, who was at her house, and told her that her husband had been killed. Having been confined that day she could not move. M'Coy then ran to Matthew Quintal, and told him to run into the bush. Quintal and M'Coy then took to the bush, and Quintal told his wife to go and tell the other Englishmen what had happened. While she was going along she called out to John Adams, who was working in his garden, and asked him why he was working this day, she thinking that he had heard of everything that had taken place. Adams did not understand her; she said no more, but went away, without telling Adams anything about the murders. The four natives then ran down to Martin's house, and finding him in his garden, ran up to him and asked him if he knew what had been done this morning. He said 'No.' They then pointed two muskets at his stomach, and pulled the triggers, and said 'We have been doing the same as shooting hogs.' He laughed at them, not suspecting anything the matter; they then immediately recocked their muskets and again pulled the triggers. The muskets going off the second time, Martin fell wounded but not killed. He then got up and ran to his house, the natives following him; when they got hold of one of the Bounty's sledge hammers, which they found in his house, and beat his brains out. They then went to Brown's house, and found him working in his garden. They fired at him and killed him. Adams, hearing the report of the guns when Brown and Martin were killed, went to see what |

was the matter. When he arrived at Brown's house he saw the four natives standing leaning on the muzzles of their guns, the butt of their muskets being upon the ground. Adams asked them what was the matter. They said 'Mamu!' (silence). They then pointed their guns at him, when he ran away, the natives following him; but he soon left them behind. He then went into Williams's house, with the intention of getting some thick clothes to go into the bush with, when he discovered that he had been killed. He however took some thick clothes from the house, and returned to his own house round by the rocks. He then took a bag from his own house, and whilst putting some yams into it to take into the bush, he was fired upon by the natives, and a bail passed in at the back of his neck and came out of the front of his neck. He then fell; when the four natives approached him and attempted to kill him with the butt end of a musket; but he guarded himself with his hand, and had one of his fingers broken by so doing. After struggling for some time, he managed to get away, and ran off and the natives after him. When he had got some distance a-head of them, the natives cried out for him to stop, which he refused, saying that they wanted to kill him. The natives then said, 'No, we do not want to kill you; we forgot what Young told us about leaving you alive for his (Young's) companion.' Adams then went to Young's house with the four natives, and found Young there. The natives then went into the mountains, armed, to try and find M'Coy and Quintal, and after several search they |

found them along with Quintal's wife, in M'Coy's house, which was up the mountain. When they found them, they were all asleep. The natives fired upon them, but did not wound any of them. They then took to the bush again. After this the four natives returned to the settlement again. One evening, when Young's wife was playing upon a fife, Manale, one of the other natives being present, became jealous at Temua's singing to Young's wife. Manale then took up a musket, and fired at Temua, which only wounded him. Temua immediately told the woman to bring him a musket to shoot Manale. Manale in the mean time reloaded his musket, and shot Temua dead. The two other natives then became much annoyed, and threatened to kill Manale. Manale then took to the bush, and joined Quintal and M'Coy; but they would not have anything to do with him until he put his musket down, which they took possession of. He then told them of what had taken place, and said that he had come to join them and be their friend. Manale then persuaded Quintal and M'Coy to go down with him to the settlement, so that they might kill the other two Tahitians. When within a few yards of the house where the natives were, Manale saw the two natives, and sprang upon the stoutest of them. Quintal and M'Coy, thinking it a scheme of Manale's to entrap them, made off for the bush again; but such was not the case. Manale soon after joined M'Coy and Quintal. Adams and Young then wrote them a letter, and sent it by Quintal's wife, to persuade them to kill their new friend, Manale; |

which they succeeded in doing, by shooting him with his own gun, which he gave them when he went to make friends with them. After this, the two remaining Tahitians again went in search of M'Coy and Quintal, when they found them under a tree. They fired upon them, but did not wound either of them. They again ran away from the natives, and, whilst running, M'Coy cut his foot with a piece of wood. The natives seeing the blood, thought they had wounded him, and then went home and told Young they had wounded M'Coy. Young then sent his wife and Martin's widow round to find M'Coy and Quintal, and to see if either of them were wounded. Young told his wife to tell them that on a certain day they all intended to kill the two remaining Tahitians, and that a certain signal would be made to that effect. These two women then returned, and told Young that neither of them were wounded. The plan was now arranged to kill these other two natives, in the following manner: – Young persuaded Brown's widow to go to bed with Tetihiti, the most powerful of the two Tahitians, and cautioned ber on no account to put her arm under the Tahitian's head when she went to sleep, as his wife intended to cut his head off with an axe as soon as he went to sleep. When Young's wife had killed this Tahitian, she was to make a signal to her husband to fire upon the other Tahitian, by shoot-him [sic] with his musket; but during the time that Young was loading his musket, the young Tahitian told Young to double load it, the young Tahitian thinking that Young was going out to shoot M'Coy and Quintal. |