|

|

The Galápagos Islands

A History of Their Exploration |

|

|

occasional papers no. xxv

of the california academy of sciences Issued December 22, 1959 COMMITTEE ON PUBLICATION Dr. Robert C. Miller, Chairman Dr. Edward L. Kessel, Editor |

|

DEDICATION

|

|

CONTENTS

|

|

PREFACE

It is not the intention of the author to compile in the present work a complete bibliography of Galápagos literature, but rather to treat of the history of the islands from the time of their discovery to the present, bringing to light historical events and documents unknown to many Galápagos students as well as giving an account of some of the men and ships connected with their history. A selected bibliography, however, is appended for those who wish to make a serious study of the flora and fauna of these islands, or for those who merely wish to read of the numerous explorers and visitors before and after the memorable voyage of the Beagle. Probably no other group of islands in the world has been the object of so much intensive study by the world's most distinguished scientists. It was amongst these now famous islands that Charles Darwin first formed his ideas as to the origin of species, and where he started on a career that made him one of the greatest naturalists of all time. The Galápagos have been one of the principal fields of endeavor of the California Academy of Sciences since its original expedition there in 1905-06, and its collections from the Galápagos Archipelago are unsurpassed. To enumerate all those who have assisted in compiling these data would make far too lengthy a list and to these my thanks are due. There are, however, those to whom I am especially indebted and without whose help the project would have been impossible: The Reverend Padre Emilio del Sol, of the Church of Santa Maria del Mercado, Berlanga, Spain, furnished the photographs of the burial place and wood carving of Fray Tomas, the discoverer of the Galápagos; Captain H. J. Hennessy and Commander W. E. May of the Royal Navy on duty at the Admiralty were most helpful, as well as the Imperial War Museum and the Maritime Museum which supplied naval photographs and prints; the British Museum Library allowed the use of old maps and diaries and the Public Records Office the data from the various old logs and letters; Mr. H. W. Parker, of the British Museum of Natural History, extended many personal courtesies; Rear Admiral Francisco Benito Perera, of the Spanish Navy, and Captain Proctor Thornton, U.S.N. (Ret.), have been most helpful in securing data regarding the early Spanish ships; the Pennsylvania Historical Society very kindly allowed the use of the Feltus diary; Dr. Paul Chabanaud, of the Museum d'Histoire Naturelle, Paris, France, secured the reports of the French vessels of war, Le Genie and Decres, ix

|

|

from the French Admiralty; Dr. F. X. Williams, formerly with the Hawaiian Sugar Planters Association, sent much information regarding the early whalers. Also, I wish to thank especially Miss Veronica Sexton, Librarian of the Academy, who was most solicitons in attending to many requests, and Mrs. Lillian Dempster, of the Department of Ichthyology, for translating the many Spanish letters connected with the research. Last, but not least, I feel deeply indebted to Mrs. Barbara Gordon, of the Academy's television staff, who so painstakingly typed the manuscript. The Author1

1 [Joseph Richard Slevin. for more than fifty-three years associated with the California Academy of Sciences in its Department of Herpetology, passed away February 15, 1957, in his seventy-sixth year. He first visited the Galápagos Islands in 1905 as a member of the Academy's Galápagos Expedition. From that date until the time of his death, he maintained an active interest in those islands and published a number of scientific and popular papers about them. The manuscript for the present paper was completed shortly before his death. – Editor.] x

|

|

THE GALAPAGOS ISLANDS

The Galápagos Archipelago, or Archipielago de Colón as it is called by the Government of Ecuador, was annexed by that country on February 12, 1832. The history of these islands remained more or less obscure to the world for many years after their discovery as they had no strategic value in the scheme of events until the construction of the Panama Canal. Then at once they became of the greatest importance to the United States as a base for the protection of that waterway in time of war, and were used as such in World War II. Any mention of a plan to lease or purchase them by the United States immediately brought a storm of protest from all Latin America and it was impossible to come to any terms with the Government of Ecuador for permanent occupancy. The archipelago, consisting of some fifteen islands and numerous islets and rocks, extends from Latitude 1°40' N. to 1°36' S. and from Longitude 89°16'58" to 90°1' W., the nearest point to the mainland being Mt. Pitt on Chatham Island, which is 502.5 miles N. 87°50' W. of Marlinspike Rock, Cape San Lorenzo, Ecuador. The equator passes through the northernmost volcano of Albemarle Island.2 The islands themselves are in reality immense lava piles projecting out of the ocean, some with perfectly formed craters, and there are hundreds upon hundreds of minor ones together with fumaroles and vents scattered over the landscape. Great lava flows extend from the crater rims to the sea. These, the most striking features of the landscape, vary greatly, some being composed of huge black or brown slabs that have the appearance of age, while others are rough, black boulders that appear to be of recent origin, so much so that one would think they had hardly cooled. Description of the Islands

Albemarle, shaped somewhat like a boot, is the largest of the group, being approximately seventy-five miles in length and forty-five in breadth at the southern end, the widest part. Narborough, James, Indefatigable, Chatham, Charles, Bindloe, Abingdon, Tower, and Hood are next in size and importance, while the remainder range from islets of a mile or less to mere rocks. 2 [The author has used the English names for islands and localities throughout his manuscript which was prepared from the English viewpoint and is published in connection with the Darwinian Centennial year of 1959. Most of these names are not official inasmuch as they have been replaced with Spanish names by the Government of Ecuador. See pages 25-26 for a list of alternatives. — Editor.] [1]

|

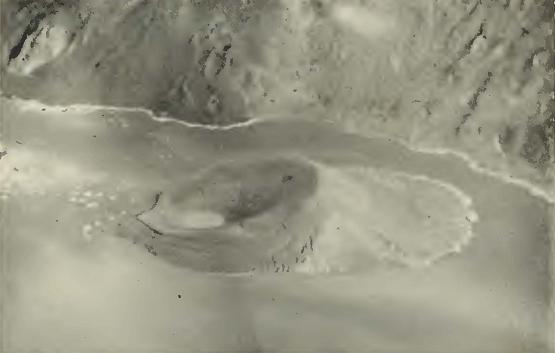

The mountains of the Galápagos are best represented on Albemarle and Narborough islands, the former having five large volcanoes, the broadest of which, Villamil Mountain, is 4,890 feet. The crater, somewhat oval in shape, is approximately five miles in diameter, and the area about the rim is open country with a scattering of small trees. As it is often covered with clouds, there is considerable moisture, resulting in a luxurious growth of grass furnishing marvelous grazing land for the wild cattle which range about the southern slope above the tree belt. The base of the mountain is surrounded by barren lava beds. Iguana Cove Mountain, 5,540 feet in height, is of a somewhat different type. The southern slopes, being exposed to the prevailing southerly winds, are covered by a dense growth of vegetation from the crater rim to the shoreline, while the northern ones are barren. The line of demarcation between lava flow and vegetation is so remarkably distinct that it is the first thing that strikes the eye while sailing along Albemarle's western coast. Cowley Mountain, 3,650 feet in height, is of still another type, the lower slopes being covered by pumice with a very scant growth of vegetation up to the vicinity of the crater rim. Here a wide belt of sword grass forms an impenetrable barrier surrounding the crater rim. The two northern mountains, Tagus Cove, 4,300 feet, and Banks Bay, 5,500 feet, are much more barren in appearance, although there is sparse vegetation at their lower levels. Neither of these mountains is as spectacular as are the southern ones, though like them they have well-formed craters. Narborough, a huge mountain of lava, is no doubt the most barren and least known of the larger islands, the greater portion of it being a series of black lava flows with only small streaks of vegetation showing on the steep eastern slope, while the southwestern slope, which is exposed to the southerly breezes, shows considerable vegetation despite the most violent eruptions that have taken place. The island rises to a height of about 4,500 feet and has a lake in the crater floor which in turn has a small crater with a lake of its own. As no anchorages were marked on the earlier charts, its waters were given a wide berth by navigators in general and landings were made from small boats while the vessel hove to off shore or lay at anchor in Tagus Cove across the strait. Mr. Templeton Crocker's yacht Zaca, while on an expedition for the California Academy of Sciences, was the first vessel to chart an ancliorage on Narborough. It was named California Cove. The great lava flows of Albemarle and Narborough vary considerably in character, some being composed of huge black or brown |

Fig. 1. Aerial view of the crater of the Narborough volcano, showing its lake which surrounds a secondary crater which has a lake of its own. Photo courtesy of Captain Paul P. Lila, U.S.A.A.F. slabs that have the appearance of great age; others appear to be of very recent origin. Two small islands of a distinct type, Duncan and Tower, have well-formed craters, the former with its lava flows covered with lichens, giving the appearance of great age. Its crater floor is composed of red volcanic ash. Tower Island, by contrast, is composed of black lava and has a crater lake of brackish water. The other larger islands, Indefatigable, James, Chatham, Charles, and Hood, are all of a somewhat different type, the main craters having broken down to the extent that they are no longer well deflned, or even visible. The tops of all except Hood, which is a very low island only about 650 feet in height, are covered with vegetation, and Chatham and Charles have open areas in the vicinity of their summits. On a visit to Charles Island in 1928, much of the open area found in 1905 had been encroached upon by a lemon thicket on top of the central plateau so that the open area had practically disappeared; no doubt the landscape changes from time to time and descriptions may not remain applicable. The tops of all the islands and of all the volcanoes have now been reached on foot by some or several members of the Academy's various expeditions. |

Mr. Rollo H. Beck, chief of the Academy's expedition of 1905-06, climbed to the top of Narborough and reported seeing the lake in the crater now shown on H. O. Chart No. 1798 from the survey of the Galápagos made by the U.S.S. Bowditch in 1942. The top of Indefatigable was reached by the members of the Templeton Crocker expedition to the (lalapagos Islands in the interests of the Academy, and Mr. John Thomas Howell, the Academy's Curator of Botany, gave an excellent description of the ascent in the Sierra Club Bulletin, volume 27, number 4, August, 1942. When the United States Army established its air base in the Galápagos, much of the area was photographed from the air. From these aerial surveys it was possible to make additions and corrections to the survey of 1835, which was in use until it was replaced by the U.S.S. Bowditch survey. Among the changes made were the listing of the crater lake on Narborough and the dropping of the supposed central crater on Indefatigable Island. The need for this addition and cor-  Fig. 2. On Tuesday, August 10, 1932, members of the Crocker Expedition to the Galápagos Islands conquered Indefatigable and were the first to see the highlands from the highest point on the island. |

rection first became known through the Academy's explorers who conquered the mountains on foot and were the first to see the crater lake of Narborough and to give a proper description of the top of Indefatigable. The latter island had defied several attempts to reach its summit. Water

For all visitors to the Galápagos, water seems to have been one of the greatest problems, and from the accounts of the early navigators they spent much time in search of it, mostly with little success. On rare occasions, when a copious rainfall occurred, a few depressions in the lava beds or the bottom of the arroyos were found to contain small amounts of water, but a generous supply where a ship could be watered from along the coast is not existent. There is one spot, how-  Fig. 3. This waterhole, about half a mile south of Tagus Cove, Albemarle Island, was found to be full by Captain Amaso Delano on August 21, 1801, and he watered his ship Perseverence from it over one hundred and four years before the Expedition of the California Academy of Sciences to the Galápagos Islands replenished the water supply of the schooner Academy from the same hole. A tarpaulin was thrown over the hole to help keep out the dust. The water was bailed out into a breaker or barrel, rolled to the water's edge and into the sea, and then parbuckled into the skiff. |

ever, on the east coast of Chatham Island (Freshwater Bay) which might have saved many an early visitor from a shortage of water if it had been discovered. A small stream trickles down from some permanent ponds on the plateau and finds its way to a basin in the rocks just above the tide line. It is this basin that was pictured in a drawing made by Midshipman G. W. P. Edwardes of H.M.S. Daphne shown at the bottom of his chart of Freshwater Bay, surveyed during the visit of that vessel to the Galápagos in 1836. On Albemarle Island, just above half a mile south of the mouth of Tagus Cove, a small basin in the tufa collected about forty to fifty gallons per day from underground seepage, and the Academy's expedition of 1905-06 watered the schooner from this basin while at anchor in Tagus Cove. It is not certain, however, whether the underground flow can be relied upon throughout the year. Again at the southern end of the island, at Villamil anchorage, some waterholes three or four miles inland furnish a moderate supply of water which, although drinkable, has a strong taste of sulphur. The grasslands about the top of the mountain have waterholes with a constant supply of good drinking water, but of course this is an impossible source as far as watering a ship is concerned. Chatham Island also has good fresh water in some parts of the plateau and water can be hauled down by ox team in case of necessity, though it is not a very practical method of watering a ship. The plateau of Charles Island, like Chatham, also has good drinking water in some springs near the base of the main peak, but the supply is not nearly as plentiful as that of Chatham. During the rainy season, at the northern end of James Bay on James Island and about opposite Albany Island, water collects in some depressions in the lava. It was here that the buccaneers invariably searched for water and, at times, found it in small quantities as they did in similar places elsewhere on the larger islands. No one need die of thirst in the higher portions of Indefatigable as the summit of that island is covered practically daily by clouds which create sufficient moisture to fill depressions in the lava and make possible its dense vegetation. Again, however, this does not help the thirsty mariner at the shoreline. A casual investigation of the Galápagos coastline will at once suffice to show the visitor why the water problem of the early voyagers was a major one. |

Introduced Animals

Of late years, owing to the activities of tuna boats and various yachts which have called at the islands, it is difficult to tell what domestic animals have been introduced and on what islands. It is known, however, that rats occur everywhere and that with the exception of pigs and cats on Indefatigable, which are a comparatively late importation, the islands listed have been inhabited as follows:

Native Fauna

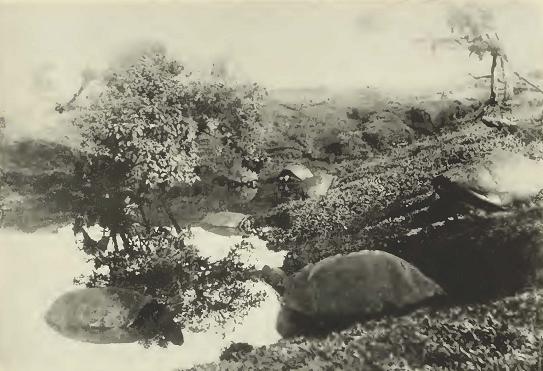

While the neighboring continent of South America, only 500 miles away, harbors birds of the most gorgeous plumage in its tropical forests and has a varied and wonderful mammal population, the avifauna of the Galápagos is most sombre, the little crimson flycatcher and the beautiful pink flamingo giving the only touches of real color. Of the Galápagos fauna, the gigantic land tortoises from which the islands get their name, galápago being the Spanish for tortoise, naturally claim first attention. These huge and grotesque reptiles have been found living in no other place in the world except the islands off southeast Africa where they no longer exist in the wild state as they do in the Galápagos. Whether the Galápagos tortoise can survive is a question. In the past they furnished a ready supply of fresh meat for the early voyagers, especially for the whalers who frequented |

the Pacific, as the waters around the Galápagos were one of their favorite cruising grounds. Tortoises were removed by the thousands during the long period of the whaling activity which started in the early 1790's and continued without decline until the 1860's. At the present time these tortoises are hard pressed by their enemies, the wild dogs being the worst if we except man. While the dogs kill the fully grown tortoises, the rats and hawks destroy the young as soon as they hatch from the egg, so that the percentage of survivors from a nest is undoubtedly small. Certainly the tortoise has an uphill battle to survive and is barely holding its own. The land iguana, formerly living in large colonies on James, Indefatigable, and Albemarle islands, is extinct on the two first and very scarce on the last, a few scattered ones still surviving at the north end of Albemarle where the dogs, owing to the extreme roughness of the terrain, have not penetrated to any great extent. Colonies on Barrington and South Seymour [Baltra], the other islands they are known to inhabit, have been successful in surviving, man being their worst enemy. The sea iguana, found nowhere else in the world, is unique in that it is the only reptile known that depends solely on the sea for its food. This inhabitant of the Galápagos is abundant and is probably the native species that stands the best chance for survival. Living along the rocky coasts where their food, a species of sea lettuce, is found, they can take to the water and swim to outlying rocks for safety, their only risk that of being caught by a shark while en route. A great danger, however, which these iguanas have to face is that of having their nests destroyed by dogs, rats, or pigs. Excluding a species of sea snake, which has been seen in Galápagos waters, and is of course venomous, a few species of lizards and harmless snakes complete the reptile fauna. Bird life is abundant on the islands and there are various types of land birds, such as hawks, owls, and flycatchers, together with the little finches that so excited Darwin's curiosity. Among the water birds are ducks, herons, and the beautiful pink flamingos which are found in the lagoons along the coasts. Like many other isolated islands, the Galápagos furnish nesting sites for thousands upon thousands of sea birds. One of these, the flightless cormorant, like the sea iguana is found nowhere else in the world. Tiie mammal and insect faunas, to say the least, are both inconspicuous, the former consisting of a bat and a few species of rodents, some of which may recently have been eliminated because of their inability to compete with introduced rats. The insect fauna consists of various types of beetles and the like, together with a few species of |

butterflies and hawk-moths, not one of which attains the beautiful coloring- of many of the species on the adjacent mainland. Native faunas tliroughout the world are having a struggle to survive and that of the Galápagos is not an exception. Besides having to contend with man for four hundred years and more, natural and introduced enemies make survival so precarious that even though the government of Ecuador has wisely made the archipelago a wildlife refuge, it is a question whether much of its native animal life will survive. It may be that the small land birds will go completely, as the cats increase, just as some species have done in other places, for example on Guadalupe Island off Baja California, Mexico. Volcanoes

The Galápagos are certainly a land of fire, but whether the Inca Tupac Yupanqui ever saw the legendary Nina-Chumbi, island of fire, no one knows. Various early voyagers were greatly impressed by the great volcanoes and invariably mention them in the accounts of their travels. In 1801, Amasa Delano observed, from his anchorage at James Bay, a remarkable eruption of one of the mountains of central Albemarle. Probably the greatest eruption ever seen, however, was that observed by Captain Benjamin Morrell of the sealing schooner Tartar when the main crater of Narborough erupted in February, 1825. His vessel was anchored in Banks Bay when at 4:30 a.m. the molten lava started pouring over the rim of the crater forming a river of liquid fire that flowed to the sea. By 11 a.m. the temperature reached 113°F. and that of the water 100°. The eruption continued and the situation of the vessel became perilous, though she was anchored some ten miles to the northward of the volcano. The heat, however, was so great that pitch in the vessel's seams melted and the tar dropped from the rigging. The following day, several of the crew complained of faintness when the temperature rose to 123° and the water to 105°. Fortunately, a light easterly breeze sprang up at 8 p.m., the anchor was hoisted, and the Tartar was able to make its way through the channel between Albemarle and Narborough islands, thus saving itself from a catastrophe. While passing through the strait, the thermometer rose to 147° and the water to 150°. By 11 p.m. the schooner anchored at the southern end of Elizabeth Bay, but as the volcano continued to erupt the heat became so intense that the anchorage was abandoned. The Tartar was still within sight of the volcano almost two weeks from |

the start of the eruption, and though the violence had subsided, the volcano was still active. This was probably as great an eruption as any ever seen by man. Narborough seems to be a particularly active volcano as Lord Byron, while at Tagus Cove on H.M.S. Blonde, observed an eruption just the year before (1825). Many late visitors have reported seeing minor craters active. A British naval officer. Captain Donald McLennan, in command of the brig Colonel Allan, who sailed from Grovesend on August 19, 1817, for the South Seas, stopped at the islands and mentioned "there are several volcanos on the Islands that are occasionally seen to burn with great fury, one of which was seen by the Colonel Allan on her last voyage, about two years since, the flames from it rose to a great height and was seen at the distance of several leagues." Captain McLennan also saw several of the minor craters of Albemarle in eruption. On the expedition of the California Academy of Sciences in 1905-06, many fumaroles were seen, and Bindloe, Abingdon, James, and the great crater of Villamil ^Mountain were all spouting steam. Dr. William Beebe, in 1925, witnessed a minor crater in eruption near Cape Marshall, Albemarle, as did Captain Lackey of the U.S.S. Memphis in 1938 and Templeton Crocker's yacht Zaca in 1933. On the voyage of Captain Allan Hancock's Oaxaca in 1937-38, a spectacular eruption of a minor crater in southeastern Narborough was observed, the molten red lava pouring into the sea, discoloring the water and killing thousands of fish. Volcanic activity is more apt to be seen in northern Albemarle and on Narborough where secondary craters are numerous. Of late years, not a single one of the main craters has shown any signs of recent eruptions with the exception of the Villamil Mountain crater, where a jet of steam has been in evidence for many years. It is here that a small sulphur deposit, claimed to be of a very high grade, has been worked at intervals. Climate

Though the Galápagos are situated directly on the equator, which would lead one to suppose that temperatures might be excessive, the islands have a delightful climate, the thermometer rarely going above 80°F. The Humboldt Current, sweeping up from the south, turns westward when it reaches the Ecuadorian coast and, passing through the southern group of the Galápagos, bathes their shores with the cool waters of the Antarctic, creating an ideal climate. The Panama Cur- |

rent, which is several degrees warmer, encircles the northern group of islands, but these, too, have a climate that is delightful. The seasons are variable and uncertain, but spring may be considered as the period between January and June, while July to December may be considered the dry season, although at high elevations, which are usually covered with clouds, there is considerable moisture. Dampier (1864) found rains in November-December and January and fair weather in May-June-July-August. The prevailing southeasterly winds support vegetation on the higher elevations and in some cases, as at Iguana Cove, it extends to the beach line. Despite the tremendous eruptions that have taken place on Narborough Island, there is a considerable green zone on the western slopes. Discovery

Whether the Inca king, Tupac Yupanqui, who is credited by Sarmiento with having discovered the Galápagos Islands, really did so is a question. As the Incas possessed no written language, the story of the voyage of the Inca king is purely legendary. The compilation of the Inca history entrusted to Captain Pedro Sarmiento de Gamboa, cosmographer of Peru, by Don Francisco de Toledo, viceroy, governor, and captain general of the kingdom of Peru, is from information given by the Inca descendants who were called upon to give testimony to the traditions handed down by their ancestors and which were supposed to have been learned by heart. The story of some merchants coming from western seas and giving glowing accounts of the land from whence they came, reached the ears of Tupac Yupanqui, an ambitious man who was not satisfied with the lands in his possession but longed for further conquests. To assure himself that the merchants of the West were giving a truthful account of their voyage, he called upon Antarqui, renowned for his magic powers, to give an opinion as to their truthfulness. Having assured the Inca king their stories were true, Antarqui set out to prove it by making the voyage to the west himself and came back with remarkable tales of his exploration. Thus assured, Tupac Yupanqui is said to have embarked with some twenty thousand men on a fleet of rafts leaving, according to Miguel Cavello de Balboa, from the coast of Manta near Guayaquil on a voyage which lasted more than a year. As the legend goes, Tupac Yupanqui sailed on and on until he discovered two islands which he named Nina-Chumbi (island of fire) and Hahua-Chumbi (outer island). These, Cavello says, may have |

Fig. 4. The Very Reverend Fray Tomás de Berlanga, Fourth Bishop of Panama and discoverer of the Galápagos Islands. (From a wood carving in the Church of Santa Maria del Mercado, Berlanga, Spain.) |

been two of the Galápagos. Upon the return from his voyage, which is supposed to have taken phice sixty years or so previous to that of Fray Tomas de Berlanga, it is stated he brought back the skin and jawbone of a horse. The Spaniards state, however, that the horse was unknown to the Indians of the New World until 1519, when Hernando Cortes landed at Vera Cruz to begin his march on the capital of the Aztecs, at which time he brought some sixteen horses to be used for cavalry mounts. Of course, it is well known that the early navigators did make voyages on various types of rafts rigged with sails and rudders, or centerboards which acted as such, but to transport an army of twenty thousand men over seas and be out for more than a year seems rather improbable. History records the discoverer of the Galápagos as Fray Tomás de Berlanga, the Bishop of Panama. He was born in Berlanga, Spain (the date uncertain), and died in the town of his birth in 1551, being buried in the Capilla del Obispo de Panama o de los Cristos of the Colegiata de Berlanga. Admitted to the Dominican Order at San Esteban de Salamanca in 1508, he obtained at Rome in 1528 the establishment of a separate province named Santa Cruz, of which he was made provincial in 1530. His territory included all lands so far discovered and to be discovered on the west coast of South America, so the then unknown Galápagos Islands came wdthin his jurisdiction. In 1533 Fray Tomás succeeded the Franciscan Friar Marti Bejar and became the fourth Bishop of Panama. Spanish conquests in the New World now saw the Empire of the Incas fall to Pizarro and his lieutenant Diego de Almagro, who extended their conquests farther southward bringing more territory into the diocese of Bishop Tomás. Eumors of dissension between the conquerors having reached the ears of Emperor Carlos V, he issued a decree dated July 19, 1534, giving the power to Fray Tomás de Berlanga to arbitrate any dispute between them and ordering the bishop to Peru on his mission. Leaving Panama on February 23, 1535, his vessel was caught in one of the calms so prevalent in those regions, and the equatorial current, setting his vessel to the westward, carried him out to the Galápagos. His letter to his Emperor is the first document ever written pertaining to them. This most interesting letter, a translation of which follows, contains the first mention of the giant land tortoises inhabiting the Galápagos and from which the archipelago gets its name, the tameness of the |

Fig. 5. Capilla del Obispo de Panama o de los Cristos, burial place of Fray Tomás. The large slab of dark slate at the foot of the altar covers the tomb. birds which has been remarked upon by most all visitors thereafter, and the grotesque iguanas which constitute another remarkable feature of a most unique fauna. Little did the reverend bishop know that he had discovered a zoological paradise that was to claim the attention of the world's leading scientists for well over a hundred years and which still continues to do so.

|

|

|

Origin

The origin of the Islands is still a question of debate. Whether they are oceanic islands thrust up from the ocean bed or whether they were formed by subsidence has claimed the attention of the most renowned naturalists and geologists from the time of Darwin's voyage on the Beagle to the present day. When Darwin, Baur, Agassiz, and many other scholars pursued their studies, they did not have the advantage of those who came after them, being entirely unaware that Pliocene fossils existed on certain of the islands; nor did they have the flora and fauna at hand that enabled later students to draw their conclusions. |

There were two distinct schools of thought on the subject. Such noted scientists as Darwin, Wallace, Agassiz, Wolf, and many others were strong advocates of the oceanic theory, while Ridgway, Gadow, Van Denburgh, Barbour, and Baur were in favor of subsidence. It was, however, more or less a general opinion amongst many that there was a Galápagos land mass extending much closer to the coast than the islands do today, but not necessarily a direct connection with the mainland. The late Dr. John Van Denburgh of the Academy's staff made an exhaustive study of the reptiles and came to the conclusion that at one time there was a Galápagos land mass that gradually broke up to form the present archipelago. Remarkably enough, he thought that Duncan Island, which shows signs of great age, was an island in a crater-like bay before the islands surrounding it were actually separated from each other. A parallel case in miniature is taking place today, the crater of Narborough containing a lake with a small crater near its center, which in turn contains a small lake. Cartography

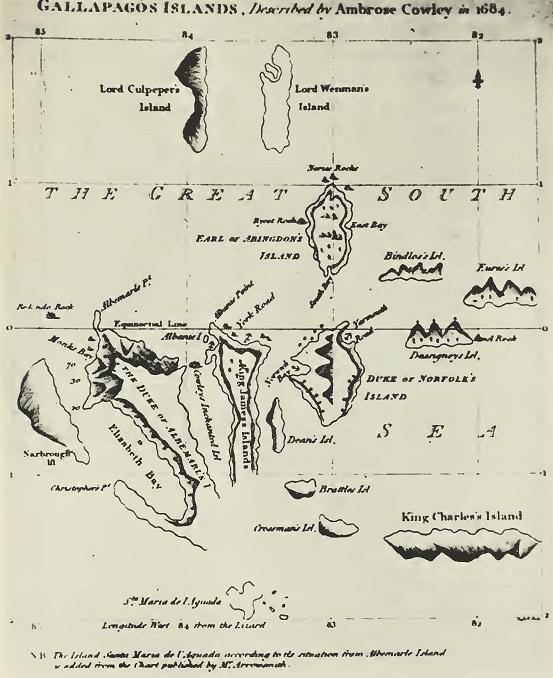

The position of the Galápagos was fairly well known to the early navigators. Bishop Tomás, while on his voyage from Panama to Peru, took the latitude and placed the islands as being between half a degree and a degree and a half south of the equator, so he was not far off in his calculations as the main portion of the archipelago does extend 1°25' south of the equator. The islands appear on Ortelius' Theatrum Orbis Terrarum, published at Antwerp in 1570, as "Insulae de los Galopegos," and in his Peruviae Auriferae Regionis Typus, of 1574 they are named "Isolas de Galapágas" and are represented as one island with two adjacent islets. The Jesuit Father Matteo Ricci's Chinese Maps of the World ( 1584-1608) show an area labeled "South Seas" and a group of islands in the approximate position of the Galápagos, though no name is given them. The early navigators placed them about two degrees to the westward of the 80th meridian, but Dampier, one of the early buccaneers, claimed they were farther to the westward, and in this he was correct as the main portion of the archipelago lies west of the 90th, and all of it to the westward of the 89th meridian. While the Galápagos appeared as early as 1570 on the chart of Abraham Ortelius, as well as on other charts by various cartographers |

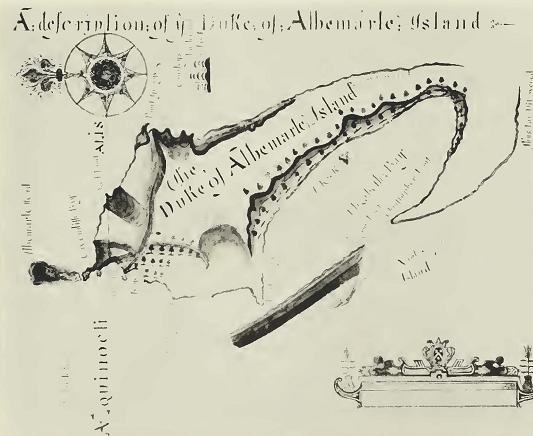

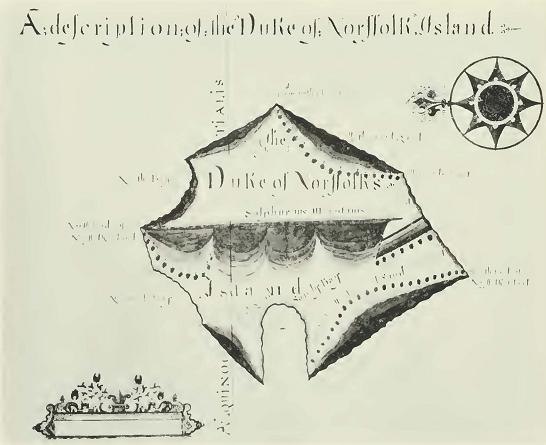

at later dates, no attempt was made to attach individual names until William Ambrose Cowley made his chart of 1684 and Captain Colnett made his in 1793-1794. They were named mostly after the English kings, admirals, the nobility, buccaneers, and early visitors to the islands. After 1570, the islands appeared on many maps of the early cartographers. A map drawn by Guilielmus Hack, in 16S4, shows the  Fig. 6. First chart of the Galápagos Islands, made by Ambrose Cowley in 1684. He also made enlarged drawings of many of the islands, two of which are shown in figures 7 and 8. |

islands without individual names and the printer's name is not given. Another map, printed for H. Moll of London, 1744, entitled A Map of South America With all the European Settlements & whatever else is remarkable from the latest & best Observations, shows the islands in their relative positions and gives the old English names, as does a chart by Samuel Dunn, printed in 1787 by Laurie and Whittle of London. A chart with no more data than the name Nueva y Correcta Carta Del Mar Pacifico ó del Sur, dated 1744, shows some twelve islands with old Spanish names used as follows: Isla de Esperanza, San Clemente, Isabel, Carenero, and Maria del Aguado. With the exception of Isabel (Albemarle), it is impossible to name them by comparing them with a modern map. Mercator in his Orbis Terrae Compendioso Descripto of 1587, represents the Galápagos as a cluster of islets just above the equator and in his map of the New World, 1622, just below it. There seemed to be no doubt to any of the cartographers that the islands were on or close to the equator. Tatton's map, of 1600, represents the archipelago by a small cluster of islets just below the equator, and Herrar's map, of 1601, is practically identical. In 1793-94, Captain James Colnett made a chart in which the islands are fairly correct as to their relative positions. This was the first chart that could be considered as at all workable. Arrowsmith of London printed a chart in 1798 which is based on Colnett's, but it is not nearly so complete inasmuch as coastlines are omitted and Indefatigable, which is called Norfolk, is represented as a mere islet. Also, much useful information given in the original chart is omitted, such as places to water and careen ships, and to gather wood. It is noteworthy that the famous Galápagos "post office" is marked on the original chart, though no mention is made of it in Colnett's log. In the early 1800's, three other charts of the Galápagos came into being and apparently were part of the work of Captain Colnett, though none was as complete as his first one. All have the same error in the coastline of Albemarle, each one showing a large bight in the southeast coast of the island. This is the worst error in Colnett's chart. It was corrected in the survey of H. M.S. Beagle in 1835. The charts in question are those of Captain Porter of the U.S. frigate Essex; Captain P. Pipon, R.N., of H.M.S. Tagus; and Captain John Fyffe of H. M.S. Indefatiqable. None of them can be said to equal the original of Captain Colnett. It was not until 1835 that a real survey was undertaken and that was done by H.M.S. Beagle under command of Captain Kobert Fitz- |

Roy, R.N. This distinonished officer made a complete survey of the archipelago and produced a real navigational chart that was published by the Hydrographic Office of the Admiralty and used by all countries from the date of the survey until the year 1942, when another survey was made by the U.S.S. Bowditch. During the cruise of the Beagle, many detailed anchorages were made on the following islands: Albemarle, at Iguana Cove and Tagus cove; Charles, at Post Office Bay; Chatham, at Freshwater Bay and Tarrapin Road; Hood, at Gardner Bay; James, at Sulivan Bay. Ships of the Royal Navy going to and homeward bound from station at Esquimault, B. C, stopped at the Galápagos on the lookout for shipwrecked sailors on their inhospitable shores. They took advantage of their various visits to plot additional anchorages. In 1846, H.M.S. Pandora surveyed Conway Bay, Indefatigable Island, and resurveyed Post Office Bay, Charles Island, and Freshwater Bay, Chatham Island. Midshipman G. W. P. Edwardes of the Daphne made a sketch of the latter spot, showing the difficulties that would be encountered watering on a rocky coast five miles off a lee shore, the prevailing  Fig. 7. Cowley's drawing of Albemarle Island. |

winds being from the southeast. In later years, two more anchorages were plotted by the British: Sappho Cove, Chatham Island, by H.M.S. Sappho, after which the cove was named, and Webb Cove, Albemarle Island, named after G. A. C. Webb, navigating officer of H.M.S. Cormorant, which made the survey. The Italian, French, and United States navies also participated in mapping the Galápagos. In 1882 and 1885, the Italian corvette Vettor Pisani visited Wreck Bay, Chatham Island, and in 1887 Midshipman Estienne of the French corvette Decres plotted an anchorage at Black Beach, Charles Island. In 1909, the U.S.S. Yorktown charted Cartago Bay on the east coast of Albemarle, and as late as 1925, a reconnaissance of Darwin Bay, Tower Island, was made by the U.S.S. Marblehead. In the last general survey, made by the U.S.S. Bowditch in 1942, there was at least one major correction, the removal of the supposed well-formed crater on Indefatigable. This crater appears on all charts to that date but is now known not to exist. Since the islands were used as a military base during World War II they have been flown over and mapped from the air, and the great mountains no longer hold any secrets.  Fig. 8. Cowley's drawing of Indefatigable Island which he called Duke of Norffolk's Island. |

In May, 1932, Captain Garland Rotch of the yacht Zaca, while on the Templeton Crocker Expedition of the California Academy of Sciences to the Galápagos Islands, made two sketch surveys of anchorages not yet charted. One of these was on the northeast side of Narborough Island and he called it California Cove. The other was Academy Bay, Indefatigable Island, locally known as Puerto President Ayora, although Academy Bay is its official name. In 1892, the Republic of Ecuador renamed the Galápagos "Archipielago de Colon," in honor of the famed mariner Christopher Columbus, and that is the official name. Galápagos, however, seems to be preferred, and is more commonly used. The survey made by Captain Alonzo de Torres, of the Spanish Navy, in 1793, under the orders of the Viceroy of Peru, was useless as a navigational chart, but added some new names to individual islands, though it is not possible to attach them to the correct ones in most cases. From a study of Cowley's map, the islands can be properly placed. The large bight on the west coast of Duke of Norfolk Island (Indefatigable) is Conway Bay and this gives a fix for Duncan Island, though the island is a little off position. Albemarle and James are decidedly so and taking this into consideration Duncan Island is the Sir Anthony Dean's3 of Cowley, and his chart reads as follows: Duke of Albemarle Island Considerable confusion has resulted from applying so many different names to the islands. The following list of the more important 3 A famous shipwright in the reign of King Charles II.

|

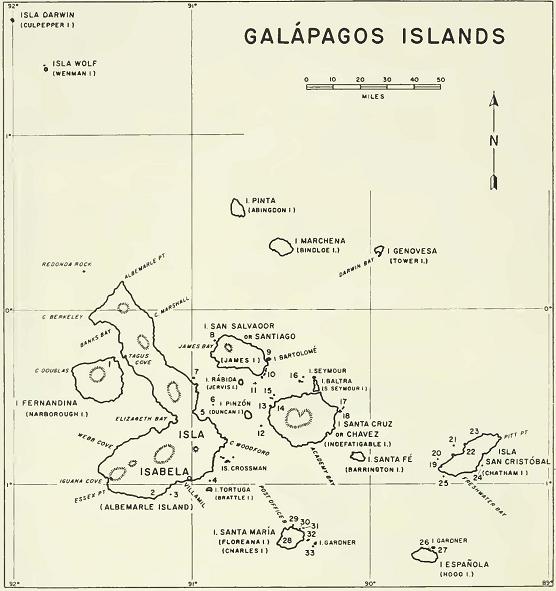

Fig. 9. Map of the Galápagos Islands with the principal islands and localities named. Minor islands, rocks, and other localities are indicated by number as follows: 1. California Cove, 2. Cape Rose, 3. Union Rock, 4. Bura Rock, 5. Cartago Bay, 6. Blanca Rock, 7. Cowley Island, 8. Albany Island. 9. Sulivan Bay, 10. Bainbridge Rocks, 11. Beagle Islands, 12. Nameless Island. 13. Eden Island, 14. Conway Bay, 15. Guy Fawkes Islands, 16. Daphne Islands, 17. Gordon Rocks, 18. Plaza Islands, 19; Wreck Bay, 20. Dalrymple Rock, 21. Kicker Rock, 22. Sappho Cove, 23. Terrapin Road, 24. Este Rock, 25. Whale Rock, 26 Lobos Rock, 27. Gardner Bay, 28. Black Beach, 29. Onslow Islands, 30. Champion Island. 31. Enderby Island, 32. Caldwell Island, 33. Watson Island. |

names will help to identify synonyms. [The present official names are printed in boldface type. — Editor.]

|

In addition to the above islands, there are a number of islets which are referred to as rocks. The principal ones are as follows: Bainbridge, Blanca, Bura, Dalrymple, Este, Gordon, Kicker, Lobos, Redonda, Union, Whale. The two outstanding rocks are Kicker Rock, off the northern coast of Chatham, which has been referred to as "Sleeping Lion," and spoken of many times by Captain Colnett as the "remarkable rock," and Roca Redonda, about fifteen miles off the north point of Albemarle. This rock was no doubt named on account of its shape, redonda meaning square sail. Both of these rocks are pictured on the chart of Captain Pipon. Both Captain Colnett on the Rattler and Captain Porter on the Essex had difficulty with the currents setting them too close to Redonda and narrowly escaped hitting it. Many of the capes and bays of the Galápagos were named after the ships which surveyed them or after people connected with the history of the islands, such as: Albemarle Island: Banks Bay, after Sir Joseph Banks, famous botanist. |

James Island: Cowan Bay (James Bay) named by Captain Porter in memory of Chatham Island: Sappho Cove, H.M.S. Sappho. Indefatigable Island: Academy Bay, American schooner Academy. EARLY VISITORS

To list all the vessels which have visited the Galápagos would be rather an impossible, as well as a useless task, many of them being mere pleasure yachts with no serious purpose in view. The vessels of the early visitors, men-of-war, and those engaged in expeditions, however, have a direct connection with the islands, being a real part of their history, and it is to these that attention is given. Before the opening of the Panama Canal, ships of the Royal Navy going to, or coming from, station at Esquimault, invariably made the Galápagos a port of call to look for shipwrecked sailors or chart some particular anchorage. Men-of-war of several nations, including the United States, Great Britain, France, and Italy, have made regular surveys, or at least a reconnaissance of certain parts of the island coastlines. After their discovery, the Galápagos were deserted for some ten years or more, their next visitor being Diego Rivadeneira who landed there in 1546. A former captain of Diego Centano who had broken relations with Pizarro and was now waging war against him, he was sent to the coast to procure a vessel in which he and his companions might escape the civil war then being waged by the Spaniards. On arriving at Arica, he, by deceit and treachery, seized a ship, deserted his commander, Centano, and put to sea so as not to fall into the hands of the conqueror, Pizarro. Like Fray Tomas, he also encountered baffling winds and currents and was carried out to the Galápagos, where, like other visitors, he arrived short of food and water. He was immediately struck by the size of the giant tortoises, the iguanas, and the tameness of the birds, which he commented on when he finally arrived in New Spain. |

Incidentally, he is the first to make mention of the Galápagos hawk, a striking and familiar bird on many of the islands. Replenishing his supplies, he once more attempted to reach New Spain and after a difficult voyage, beset by calms and currents, landed in what is now Guatemala. Strange to say, he, like the discoverer, gave no name to the land he had visited. When in 1573, Basco Nunnez de Balboa marched across the Isthmus of Darien, he climbed the mountains forming the backbone of the isthmus and was the first European to see the waters of the Pacific Ocean. From his position, on the top of the mountain ridge, the waters of both the Atlantic and Pacific were visible. The isthmus extending in an easterly and westerly direction, he had the Atlantic at his back to the north and the Pacific to the south, which he called the South Sea and by which name it was thereafter known to the early navigators. In these waters, bordering Central America and northern South America, the buccaneers spent much of their time looting and burning the coastal cities and towns and capturing the Spanish ships they encountered. It was the Galápagos they used as a base to victual, fuel, water, and careen their ships while cruising these waters in search of their quarry. Among the most famous were Davis, Cook, Wafer, Knight, Dampier, Ambrose Cowley, and John Eaton. On April 8, 1684, Captains Eaton and Cook in the Nicholas and Bachelor's Delight sailing from Juan Fernandez to the American coast, sighted one of the eastern islands of the Galápagos on May 31, 1684. On board these ships were Dampier, Cowley, and Davis. Proceeding to James Island, anchorage was made on the west coast, to the southward of Albany Island. Cowley named this anchorage Albany Bay and it was thereafter one of the favorite spots of the buccaneers, as it was here they found an abundance of tortoises, fire wood, and, in the rainy season, a sufficient supply of water for their ships. Some one hundred years after. Captain James Colnett in the ship Rattler visited this very spot and mentioned that some of his crew found old stone jars, daggers, and implements of iron scattered about. Here, the buccaneers erected shelters and made caches of provisions to replenish Iheir stores on future visits, and it was here that Dampier remarked that the tortoises were very fat and that the oil saved was stored in jars and used instead of butter to eat with dumplings. On this visit, the presence of snakes in the Galápagos was first mentioned, when Dampier said "There are some green snakes on these islands." Among the precious documents preserved in London are the diaries of two of these buccaneers, Cowley and Davis, and as they deal so inti- |

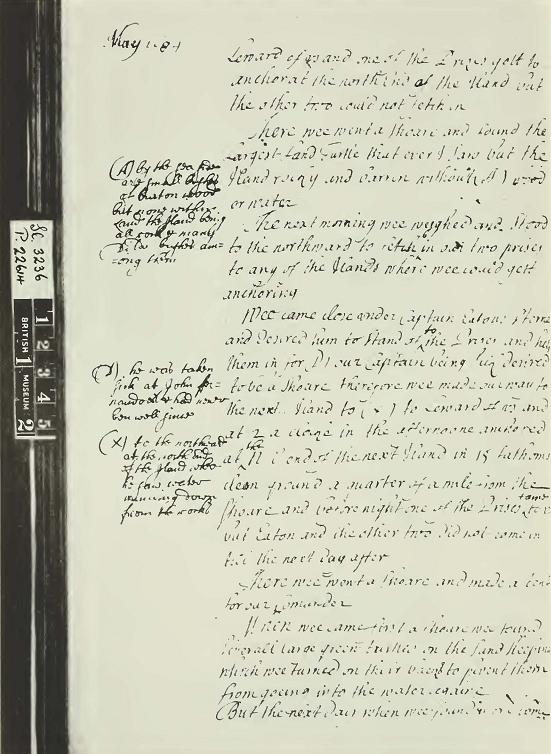

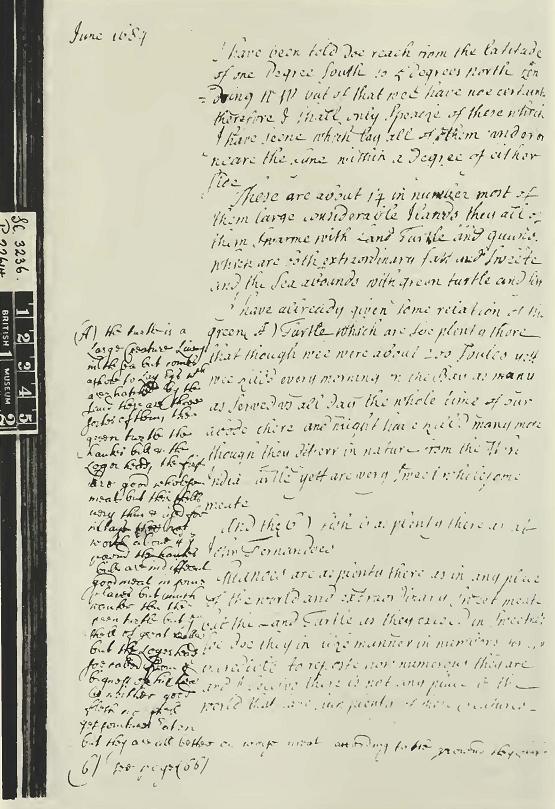

mately with the early Galápagos history, specimen pages of them are reproduced, with the permission of the British Museum, given from photostatic copies of the originals. To portray a true picture of the life of a buccaneer in the Galápagos over 200 years ago, transcriptions of several pages of each diary are given below.4 Excerpts from the Journal of Ambrose Cowley

* |

Fig. 10. The first of three pages from the diary of Ambrose Cowley. See the accompanying transcription of this page and those shown in figures 11 and 12. |

Fig. 11. The second of three pages from the diary of Ambrose Cowley. ————— |

|

barren dry Ilands. I must confess my Curiosity would have carryed me further in search to find any thing profital on them but our business was not to search places to settle in, only to finde conveniencies  Fig. 12. The third of three pages from the diary of Ambrose Cowley. |

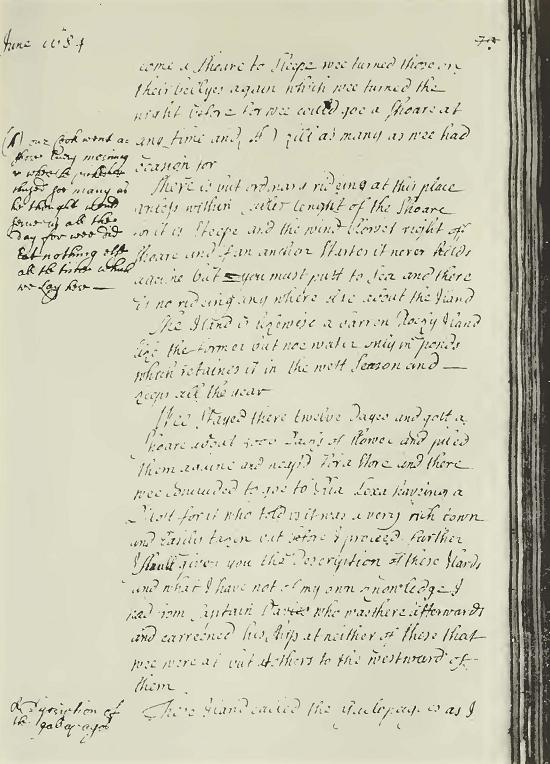

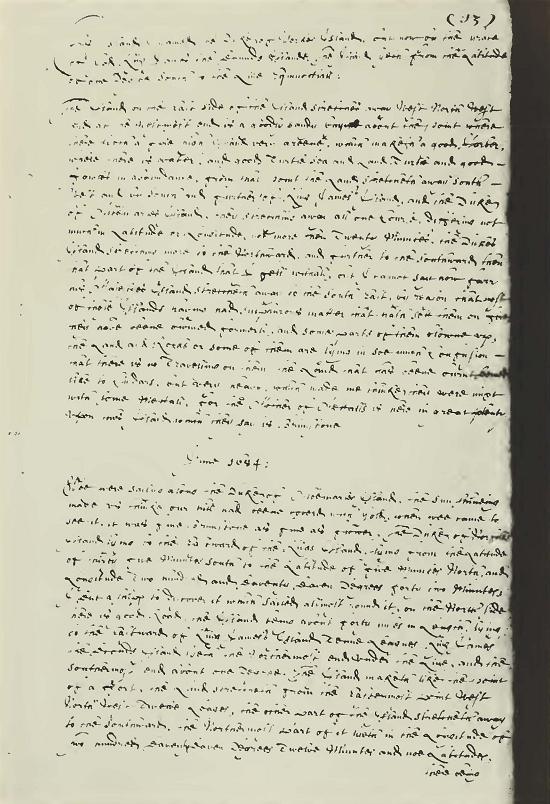

Excerpts from the Journal of Edward Davies5

5 Ambrose Cowley is followed in the spelling of Davies though it is commonly found Davis in the literature. (A [3]) when he was here the second time Eat nothing but Land turtle and gave 6 or 7 Jars of oyle for each mess |

Fig. 13. A page from the diary of Edward Davies. See the accompanying transcription. |

|

Raveneau de Lussan, a contemporary of Cowley and Davis, made some interesting remarks of his voyage to the South Seas in 1684. His journal states:

The following year (1685) Davis, accompanied by William Knight, a fellow buccaneer, made a second visit to the Galápagos. On arrival he took on some of the stores from the cache made on his previous visit and sailed for the coast of South America. Davis apparently appreciated the islands as he again returned in 1687 for his third visit to victual and careen his ship. After drying some fish, salting the flesh of the land tortoise, and filling sixty eight-gallon jars with the oil of the land tortoise while he was repairing his ship, he again set sail for the South American coast. |

A later buccaneer was Captain Woodes Rogers, an Englishman, who, in 1708, with a commission from the Lord High Admiral, set out for the South Seas in the ship Duke accompanied by Captain Stephen Courtney in the Duchess. Kogers was financed by some merchants of Bristol with instructions to war against the Spaniards and the French. On May 8, 1709, Rogers left the coast of Peru bound for the Galápagos, which he sighted on May 16. The failure to water his ships before leaving the mainland prevented any lengthy stop and he left for the mainland to do so. September 10 found him back at the Galápagos where he took on a supply of tortoises and wood and left again to loot and burn the towns of New Spain and capture any Spanish ship he might encounter. Though the buccaneers had not entirely ceased operations, another type of seaman appeared in Galápagos waters for the purpose of exploration and annexing new lands. One of the earliest of this type was M. de Beauchesne Gouin, a captain in the French navy, sent out by a company formed in France for the purpose of establishing colonies in the countries of South America not yet occupied by Europeans, and also for trading his cargo with Spaniards, although they were forbidden to trade with any but their own countrymen. He sailed from France on December 17, 1698, on board the frigate Philippeaux accompanied by the bark Maurepas. After a four-months visit to the ports of Chile and Peru, Beauchesne sailed for the Galápagos, arriving there on June 7, 1700. Ensign Le Sieur de Villefort, of the Philippeaux, reported that neither fresh water nor trees were found, but an abundance of fish and tortoises were found to refresh the crews. From his description of the anchorage, his mention of a small island and the finding of the materials for the repair of ships, the Fhilippeaux must certainly have been anchored in what the buccaneer Cowley called Albany Bay, James Island, the isle referred to as Isle a Tabac by Villefort. According to his diary, the other two islands visited. Health Island or Isle de Saute, and the Isle Mascarin, are no doubt Charles and Hood in the order mentioned. At the latter island, he remarked with surprise the sighting of a number of large whales so near the line. After a stop of just a month, he headed south for the passage round the Horn and his return to Europe. In 1720 Captain Clipperton, Dampier's chief mate and discoverer of the island named after him, touched at the Galápagos to replenish his supplies for his voyage to the Bay of Panama, but makes no special mention of his activities. He cruised the South Sea, captured |

two or three prizes, plundered the town of Truxillo, and finally left for China. The voyage of Captain James Colnett, R.N., was no doubt the most outstanding of the early voyages. In 1792, Captain Colnett w^as commissioned by His Majesty's Government to investigate the possibilities of spermaceti-whale fisheries in the South Sea and his appointment was received with great pleasure by Samuel Enderby & Sons, leaders in the whaling industry of Great Britain. The matter of a proper vessel for the voyage was a problem as there was none for sale on the market. The Admiralty was petitioned for the loan of a vessel and His Majesty's sloop-of-war, Rattler, of three hundred and seventy-four tons was selected. The alterations necessary for such a voyage would make it impossible to turn the vessel back to the Navy for further use as a vessel of war, so the firm of Enderby & Sons agreed to purchase it on release by His Majesty's Government. This having been agreed upon, H.M.S. Rattler was stricken from the register and Enderby & Sons stood the expense of the alterations. Captain Colnett was granted a leave of absence to make the voyage and the Rattler became an ordinary whaler. The voyage of this vessel is so intimately connected with the islands that its log which follows will be of deepest interest to any student of Galápagos history. Before the extended visit which began on March 13, 1794, Captain Colnett made a short stop from June 13 to 28, 1793, when, on account of unfavorable wdnds, he sailed for the mainland. However, on June 25, he hove to long enough to send a boat ashore to look for water, which, on finding none, brought back a tortoise and several turtles. On June 27, he sent two boats ashore to look for water, both of which met with no success. the Rattler then was headed toward the Coast and did not return to the Galápagos until March 12, 1794, when Colnett starts the log of his second visit. The account of the June, 1793, visit is as follows:

|

|

The Rattler then left for the coast of Peru and did not return until March 12, 1794, when the second visit began.

On March 13, 1794, the log is headed "At the Galápagos Isls."

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

No mention is made of hoisting anchor on May 13 and the entry for the next day shows the ship at sea: "Left the Galápagos for the Coast of Peru." Another visitor of note was Captain George Vancouver in His Majesty's sloop-of-war Discovery. On Tuesday, February 3, 1795, Vancouver passed between Culpepper and Wenman, remaining in sight of them for two days, being harassed by light and variable winds, but making a little progress toward the south he came within sight of Albemarle, Narborough, and Roca Redonda. Proceeding southward along the Albemarle coast, a boat was put off and a Mr. Whidbey and Mr. Archibald Menzies, botanist of the expedition, made a landing to the southward of Cape Berkeley to examine the character of the country. Finding the shores afforded neither fuel nor fresh water, the landing party remained on shore only a short time, but noted the adjacent area was subject to much volcanic activity, and, on February 9, Vancouver concluded his examination of the Galápagos shores and headed southward. Amasa Delano, an early explorer, made his first stop at the Galápagos on his voyage around the world in 1801. He made consid- |

erable comment concerning the natural history, particularly on the giant land tortoises and the iguanas. He is the first to remark on the small lizards (Tropidurus) known as lava lizards, probably being struck by the brilliant red coloring of the head and the sides of the neck. He gives an excellent description in his journal of the waterhole in the vicinity of Tagus Cove, northern Albemarle, from which he watered his ship, and which was used by the Expedition of the California Academy of Sciences to the Galápagos Islands over one hundred years later. Lord Byron, commanding H.M.S. Blonde, found this waterhole nearly dry when he visited it for the purpose of watering his ship on March 27, 1825, and, as a consequence, his crew went on short rations. ENDERBY WHALERS

Even before the voyage of the Rattler, British and American whalers had entered the Pacific and were in Galápagos waters. Samuel Enderby & Sons were the leaders in the British whaling industry and were sending ships to the South Pacific as early as 1788. In that year, Samuel Enderby and Sons fitted out the whaler Emilia for a cruise around Cape Horn, and a letter to George Chalmers, Esq., dated Paul's Wharf, June 28, 1790, gives notice of her return: "The ship Emilia, James Shields, Master, returned from a whaling voyage on the Coast of Peru last March. As she was the first ship that ever whaled in the Pacific Ocean, we put on extra quantity of all stores to preserve the health of the crew on so inhospitable a coast." A second letter states: "We are the only owners who have sent a ship around Cape Horn. Some owners object to the confinement of the Latitude, others to the time the act obliges them to stay out, which is 18 months." Enderby complained to the Crown about the difficulty of getting stores left over in the King's warehouse, petitioning to have them left there and take an oath that the duty had been paid on them. From this voyage, the Emilia returned with 140 tons of sperm oil and 888 seal skins. In 1788, Enderby and Sons had four whalers listed as going to the westward of Cape Horn:

|

In addition to these, five other vessels with various owners are listed:

The early days of whaling were not without their perils, as indicated by the letter of Samuel Enderby to Lord Hawsbury, dated February 4, 1790:

Samuel Enderby, Jr., voyaged to Boston to get information concerning the whale fishery and engage Nantucket men to come to England and sail on the British whalers. One of his rivals in whaling, Alexander Champion, for whom an islet in the Oalapagos is named, was desirous that the whaling in the Pacific should be carried on from Britain, so that there was considerable rivalry among the whale men. Samuel Enderby, however, seems to have been acknowledged as the leader in the industry; a memorial to him, dated January 21, 1786, states:

Enderby realized a large fortune from the whaling industry and passed away in 1798, at his home in Blackheath, in his seventy-ninth year. |

The British were not alone in the whaling industry in Galápagos waters as the New England whalers were very much alive to the value of the Galápagos whaling grounds, and in 1791 six whale ships, one listed as being fitted out at Nantucket, sailed for the Pacific:

The late 1860's saw the end of the whaling industry on a large scale, the sinking of the "Stone Fleet" and the ravages of the Confederate cruiser Shenandoah in the northern Pacific raising such havoc that it was never restored. VISITING MEN-OF-WAR AND SEALERS

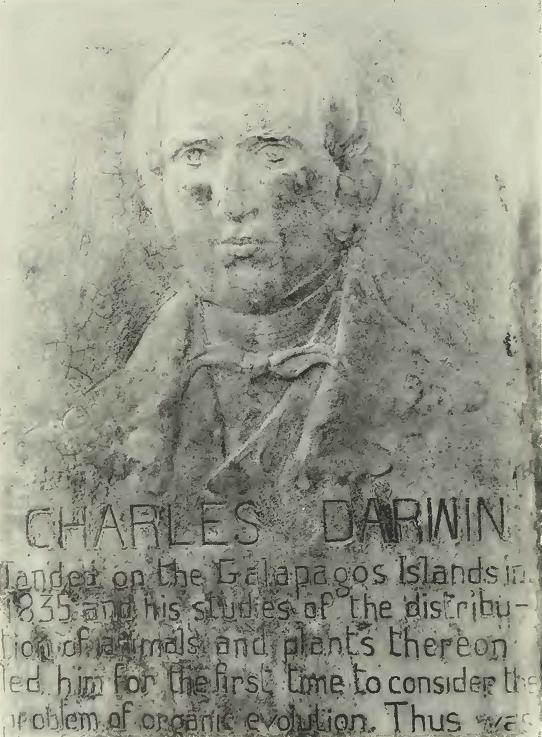

From 1800 on, whalers, sealers, and the warships of various nations were frequent visitors. In 1825, H.M.S. Blonde, the Right Honorable Lord Byron commanding, anchored at Tagus Cove, Albemarle, while en route to the Hawaiian Islands with the bodies of King Kamehameha II and his consort, both of whom died in London while guests of the British Government. Although Lord Byron remarked about the tameness of the birds and beasts (no doubt the sea iguanas), strange to say he made no specific mention of the giant land tortoises which must have been abundant at the time of his visit, especially on Albemarle. In 1822, Captain Basil Hall, while in command of H.M.S. Conway, made a stop at the southern point of Abingdon Island, where he set up his instruments to determine the compression of the earth at the equator. Though he was only about half a degree north of the line, he reported that his results were not as satisfactory as those made in his own country. During the stay of the Conway, Captain Hall experienced a phenomenal temperature for the Galápagos, the thermometer rising to 93°. His schedule did not permit a longer stay, so the ship was stocked with tortoises, numerous on Abingdon in those days, and sailed from the Galápagos. Though the voyage of H.M.S. Beagle to the Galápagos in 1835, with Charles Darwin as naturalist, was of short duration, the visit being only of five weeks, in which Chatham, Charles, James, and Albemarle islands were visited (Sei)tember 15-October 20), it is by |

far, and always will be, the most famous, for his theories propounded from his studies made on the voyage upset the scientific world of that day and his writings pertaining to the voyage are still held as classics by the world's naturalists. The islands further claimed the attention of the Royal Navy when, on April 6, 1838, H.M.S. Sulphur, Captain Sir Edward Belcher commanding, set sail from Cocos Island for the Galápagos and made Abingdon Island on April 18, passing within two miles of the west shore. After three days of experimenting with currents and temperatures, the Sulphur w^as caught in a calm and finally made Callao Roads some twenty days later. The visit, in 1846, of H.M.S. Herald, Captain Henry Kellett commanding, and accompanied by H.M.S. Pandora, is interesting in that its naturalist, Berthold Seeman, states that no tortoises were found and that there were numbers of wild dogs on Charles Island. Besides numerous goats and pigs, the settlement claimed about two thousand head of cattle. The descendants of these animals still run wild on the island and are responsible for considerable destruction. The elevation of the settlement was given as 461 feet, and the position approximately where the permanent springs are at present. On February 4, 1870, Read Admiral Sir Arthur Farquar, on his flagship H.M.S. Zealous, visited Charles Island and an account of the cruise was compiled by the officers of the ship. Ten years later (1880), Rear Admiral Frederick Henry Sterling was a visitor on his flagship, H.M.S. Triumph, but made no special comments. In those days, it was customary to be on the lookout for ships in distress or for shipwrecked sailors. H.M.S. Hyacmth, in 1895, while returning to England from station at Esquimault, anchored at Black Beach Roads, Charles Island, and two of her lieutenants, Wintour and Chadwick, gave a thrilling account of being attacked by "huge Spanish mastiffs" as they headed up the trail for the springs. British ships of war continued to call intermittently to as late as 1913. As far as the Royal Navy was concerned, the year 1905 saw the beginning of the end of the Esquimault Naval Station, when the number of ships was reduced from seven to one, leaving the lone gunboat Shearwater to make the annual patrols to the north in the summer and to the south in winter, when it visited the Galápagos in search of stranded sailors or shipwrecks. |

The Italian corvette Vettor Pisani, G. Palumbo commanding, visited the Galápagos in 1884-1885, where it surveyed Wreck Bay and visited Duncan Island. Here it was reported as taking some tortoises and making botanical collections on Charles and Chatham islands. Captain Francisco Vidal Gormaz, of the Chilean Navy, visited the islands on the Chacabuco in 1837[sic - 1887] and wrote of his experiences in Del Anuario Hidrografico, volume 15, 1890. An American frigate, the Potomac, Commodore John Downes commanding, arrived at Charles Island on September 30, 1833. He was formerly First Lieutenant of the Essex on Porter's famous cruise. Downes found the colony established by Villamil, a Frenchman, who, after the Louisiana Purchase, had left that territory and obtained a concession from the Government of Ecuador to establish a colony on Charles Island, Ecuador having annexed the Galápagos. At the time of the visit of the Potomac, Villamil's colony was doing a flourishing trade with the whaling ships, selling them such produce as vegetables and fruits. Downes reported that during a single year thirty-one whalers had stopped at Charles Island to replenish their supplies and to take on water. Some tortoises, close to the last of the native ones, were brought to Boston. By 1846 the tortoises native to the land were practically extinct owing to the steady demands of the whalers. Although United States men-of-war were not as frequent visitors as those of Great Britain on account of the Esquimault Naval Base, the flag was shown there from time to time. In the early 1900's the U.S.S. Rochester, formerly the New York of Spanish American War fame, called at Stephens Bay, Chatham Island, to be followed in 1909 by the first squadron of the U.S. Pacific Fleet, commanded by Rear Admiral William T. Swinburne on his flagship West Virginia. The French frigate La Venus, Admiral Abel du Petit Thouar commanding, spent from June 21 to July 15, 1838, in Galápagos waters. There are no records of her adding anything to our knowledge of the tortoises, but during her stay some birds were taken and botanical collections were made on Charles Island. These are now housed in the herbarium of the Museum d'Histoire Naturelle, Paris. The Swedish frigate Eugenie, Rear Admiral C. A. Virgin commanding, with Dr. Kinberg as zoologist and Professor N. J. Andersson as botanist, was a visitor in 1852, calling at Albemarle, Charles, Chatham, Indefatigable, and James, where general collecting was undertaken. According to the traditions of the sea, the frigate picked up a |

stranded man while at Charles Island and the following is a translation of an entry which was made in the log:

The Eugenie's arrival in Honolulu was was given considerable notice, including the following in the Marine Journal, Port of Honolulu:

The Friend noted the Eugenie's arrival as follows:

Among the many vessels engaged in the fur trade in the Pacific during the middle 1800's were the ships Atala, O'Cain, Avon, and the schooner Traveler, all of which were in Galápagos waters in 1816-1817. The brig Tamaahmaah was there in 1825. No doubt these vessels were attracted by the Galápagos fur seal, which, on account of persistent hunting, has now become an extremely rare animal, being confined to Tower Island. And, of course, the whalers did not hesitate to "knock off whaling for a spell" if they saw the opportunity to gather a sizable cargo of seal skins. Sealers and whalers were particularly active in those days and as communications were not as they are at present, it was customary to speak to each other at sea and then to report on arrival at their destinations in order that the news might be published and ship owners |

be advised as to the whereabouts of their vessels, and whether the catch was good or bad. The shipping news was eagerly scanned by mariners in general, and the following items from the early maritime news published in Honolulu, an important port of call for whalers, shows how valuable it was and how favored Galápagos waters were as a whaling ground.

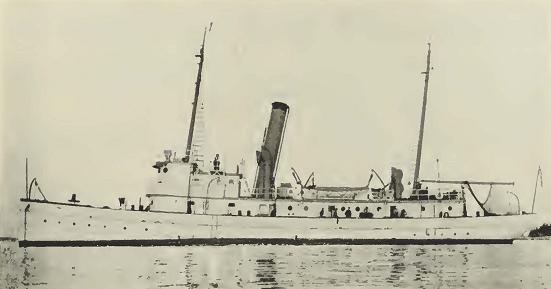

THE UNITED STATES FRIGATE ESSEX

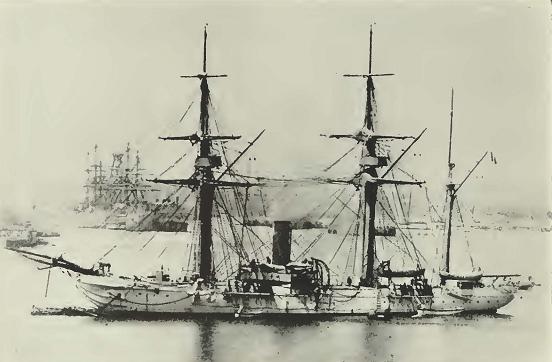

On April 17, 1813, the United States frigate Essex, David Porter, captain commanding, arrived in Galápagos waters and, next to H.M.S. Beagle, is the most famous ship connected with the history of the islands. This little vessel of 860 tons and 32 guns practically destroyed the British whaling fleet in Galápagos waters and was a continual source of worry to the British until her capture at Valparaiso, Chile, March 4, 1814. Despite the heavy burden upon his shoulders. Captain Porter made many interesting observations on the fauna of the Galápagos while on his cruise, and was the first to remark on the differences in |

Fig. 14. The U.S. frigate Essex. Captain David Porter commanding, made history in Galápagos waters during the War of 1812 and vies with H.M.S. Beagle as being the most famous ship connected with their history. the tortoises of the various islands, being struck primarily by the shape of the shell, the dome, and saddle back varieties. Also, he made remarks on the lava lizards (Tropidurus), probably being struck like Captain Delano by the bright red colors of the head and throat on some species. On August 4, 1813, the Essex arrived in James Bay. Porter states that he dropped anchor in six fathoms of water, within a quarter of a mile of the middle of the beach over a soft and sandy bottom. He moored with the bower anchor to the southward and the stream to the northward, the SW part of Albany Island bearing NW X N, Cape Marshall, Albemarle, NW and the west point of the bay SW X S. While here, Porter landed four goats and some sheep from the Essex, and, as he states, they being so tame, left them without a keeper, carrying water ashore for them each morning. One morning, however, they disappeared and a searching party failed to locate them, so he concluded they had found some fresh water and would remain inland.6 6 These animals were afterward seen by the crew of H M.S. Tagus on July 30, 1814. |

Porter, as did other early visitors, made a chart of the Galápagos, which is now in the files of the Admiralty. Many valuable papers, however, must have been lost, especially those of the chaplain, David Adams, who, being a surveyor, was sent by his captain to explore the islands in detail. On capturing the Essex, Sir James Hillyer, commanding H.M.S. Phoehe, stated, "There has not been found a ships book or paper of any description (charts excepted) on board the Essex." One of the tragedies on Porter's cruise was the death of acting Lieutenant John S. Cowan, who was killed in a duel with Lieutenant of Marines, John M. Gamble. A misunderstanding between the two officers resulted in a duel being fought on the beach at James Bay, and Cowan, victim of the code of dueling, forfeited his life. His remains were buried with the honors of war on August 10, 1813, Porter renaming the bay Cowan Bay in honor of the deceased officer. Niles Weekly Register (1814-1815) gives the following account of this affair which so saddened Captain Porter and deprived him of a valuable officer:

|

earth where he remains rested, and on it were inscribed, by his friend Lieutenant M'Knight. the following monumental lines:

The only record found of anyone visiting Cowan's grave since the date of his burial is that of Lieutenant John Shillibeer, Royal Marines, who makes the following remarks concerning the stop of H.M.S. Briton to James Bay on July 17, 1814:

Before leaving the anchorage, Porter buried a bottle near the head of Cowan's grave with a letter to his First Lieutenant John Downes. As the latter never returned to James Bay, this bottle must still be intact. In recent years, efforts have been made to locate the grave of Lieutenant Cowan without success. On the Third Presidential Cruise of the U.S.S. Houston, Captain G. N. Barker, U.S.N. , commanding, a stop is recorded at James Bay where a futile effort was made to locate the last resting place of Cowan. A serious attempt was made by the late Captain Sherwood Picking, U.S.N., when on board the U.S.S. Mallard in 1941. He visited James Bay and his search also proved unsuccessful, leaving the resting place of Lieutenant Cowan still a mystery. This unfortunate affair in no way aff'ected the career of Lieutenant Gamble. He was given command of one of Porter's prizes, the |

Greenwich, and after many harrowing experiences survived the war of 1812. He passed away on September 11, 1836, as Brevet Lieutenant-Colonel in command of the marine garrison at New York. With him, while in command of the Greenwich, was Midshipman William W. Feltus, a youngster of fifteen, who was killed by the natives while landing at Nukuhiva in the Marquesas, where Porter had gone to repair the Essex and throw the British frigates in search of him off the track. Gamble, no doubt, saved the boy's journal and brought it back to the United States where it is now preserved in the archives of the Historical Society of Pennsylvania. His own, in possession of his grandson, was destroyed by the great San Francisco Fire of 1906. The journal of Midshipman Feltus is a most interesting account of the daily life aboard a Yankee man-of-war and gives many items of interest to the Galápagos student. The part given pertains only to his experiences in those islands:

|

|

|

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

1 Probably meant for Santa Elena. |

BRITISH FRIGATES BRITON AND TAGU8

Following the Essex by a year, two of His Majesty's frigates, the Tagus, Sir Thomas Staines commanding, and the Briton under command of Captain P. Pipon, visited the Galápagos. The items from the captains' logs are most interesting; in addition to mentioning the goats put ashore by Captain David Porter of the Essex, they comment on the number of tortoises taken and the allowance rationed to the crews, and, as always, the search for water:

|

|

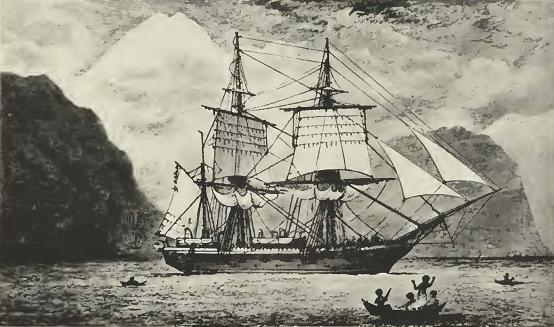

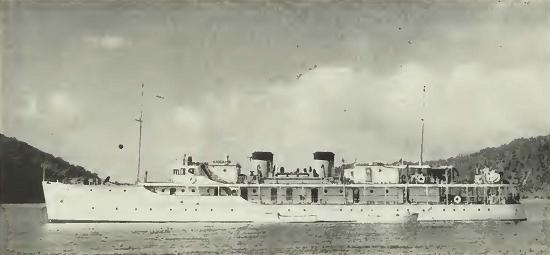

HIS BRITANNIC MAJESTY'S SHIP BEAGLE, THE

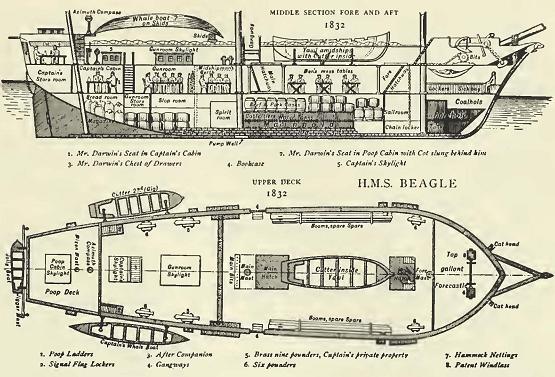

MOST FAMOUS SHIP CONNECTED WITH THE HISTORY OF THE GALAPÁGOS Since the founding of the British Navy, its ships and their histories have been an inspiration to those who were to follow in the footsteps of their great admirals, the mere mention of such a ship as the Victory filling the heart of every Englishman with pride. However, Darwin's ship, the Beagle, was too insignificant to command any attention, and it was not until after the return of Charles Darwin, the naturalist on board, and the publication of the results of his voyage, Journal of Researches into the Geology and Natural History of the Various Countries Visited by H.M.S. Beagle, that it became one of the famous ships of His Majesty's Navy.  Fig. 15. His Majesty's Ship Beagle hove to in the Strait of Magellan, |

It is truly amazing that the modern chart of the Galápagos made in 1942 by the U.S.S. Bowditch, a vessel 380 feet in length and 6,000 tons displacement, equipped with every modern device for marine surveying, should so closely approximate the survey made by Captain Fitz-Koy over a hundred years ago. His little vessel was at the mercy of strong and uncertain currents together with deadly calms so prevalent in those regions. Certainly no greater tribute could be paid to the Beagle's commander. In this day and age when radar, wireless, sonic depth finders, and various other aids to navigation are commonplace aboard ships, those who have read Darwin's journals might be interested, and many are, to know what sort of vessel it was in which Darwin made his famous voyage and accomplished so much on that famous five-year cruise. The Beagle left England on June 27, 1831, and was paid off at Woolwich November 17, 1836. Designed by Sir Henry Peake, Surveyor of the Navy, she was launched at the Woolwich Yards, London, England, May 11, 1820. The Beagle was classed as a sloop, rigged as a brig, and had a displacement of 235 tons. The length of the gun deck was 90 feet; the length of keel for tonnage was 73 feet, 7 5/8 inches; the extreme breadth was 24 feet, 6 inches; the depth in the hold was 11 feet; light draught of water, forward it was 7 feet, 7 inches, and abaft it was 9 feet, 5 inches; the armament on the gun deck was 26-pounder guns and 8 18-pounder carronades. She carried a complement of 75 men. In 1808, some thirty small brigs were built for the Royal Navy, and a few more in 1813. The same design was used from 1818 onward, the last being the Termagant of 1837, so the Beagle came under this master plan of 1818. Like vessels of her day, she was stoutly built, her deck beams being approximately a foot in width and had what is known as a welldeck with t'gallant fo'c'sle and poop deck, the compartment below being fitted as a chart room. Although vessels of this size were sometimes steered with a tiller, the Beagle was fitted with a wheel. Captain Fitz-Roy made several suggestions regarding alterations while the vessel was being overhauled, and for the comfort of the crew the spar deck was raised twelve inches forward and eight inches aft. She had none of the modern inventions, such as turnbuckles for setting taut the standing rigging, this being done with lanyards and dead eyes with block and tackle as power. For bracing the yards, there were no pendants with luff tackles or double purchases, the braces being |

whips and power gained by more men tugging on the hauling part, and to board the main tack in a stiff breeze, even on a vessel the size of the Beagle, meant plenty of man power.

The main deck was given over to living quarters, the captain's room aft taking up the entire width of the stern. Forward of this were the officers' rooms along the sides and the midshipmen's quarters, and forward of these were the warrant officers' rooms and store rooms. A small locker, or bin, as it was called, took up the midship section, with the galley just abaft the foremast. The seamen swung their hammocks from the main hatch forward. The lower hold was given over to supplies, ammunition, coal, various stores, and that all important item, water. Even with the crew reduced to fifty-eight, when one stops to consider the vessel was only ninety feet in length, it can readily be seen that accommodations were anything but de luxe. The sail plan is not available and the drawing of the vessel made while in the Strait of Magellan does not show her with the royal yards in place, though it does show that she carried single topsails. Ten-gun brigs of the Royal Navy did carry royals, but in stress of weather or for various reasons, the t'gallant and royal yards were sent down and stowed in the shrouds. This was probably the case with the roval vards when the sketch was made. |

The records show she remained at Woolwich until 1825 when she was allocated to surveying service by admiralty order of September 17, 1825. Her armament was reduced from 8 to 4 carronades and her complement from 75 to 58, while so employed. On September 27, 1825, the vessel was docked at Woolwich to be fitted for surveying Magellan Strait, copper taken off, sheathed with wood and re-coppered. Her rig was changed to that of a bark in order to facilitate her maneuvering, and on September 7, 1825, Commander Pringle Stokes became her first commanding officer. On his death he was succeeded by Commander William George Skyring as acting commander until Commander Robert Fitz-Roy took over until the end of her first commission, October, 1830, when she was paid off at Woolwich. During the second commission of the Beagle, June 27, 1831, to November 17, 1836, he took command once more and although he was promoted to captain during the cruise, and was eligible to command a ship of the first rate, he still continued his duties as surveyor in command of the Beagle. On fitting out the vessel for its cruise into the Pacific, Commander Fitz-Roy made many requests in order to make the vessel as comfortable as possible for the crew and to facilitate his work. That the admiralty had great confidence in him is shown by the fact that his many requests were granted even to the minutest details. The following correspondence with the Naval Board in regard to the outfitting of his command shows with what care he prepared for the voyage which ended so successfully: [P. Rt. Adm. 106/1346 F. Off Capt Fitz-Roy (Lihon's Rudder) ]t

7 [Many of these letters bear file designations and comments as well as endorsements by officials, with or without their initials. All of these are enclosed in brackets so that they will be distinct from the original text. In a few cases the parenthetical material may be that of the author. — Editor.] |

|

|