|

THE REAL STORY

|

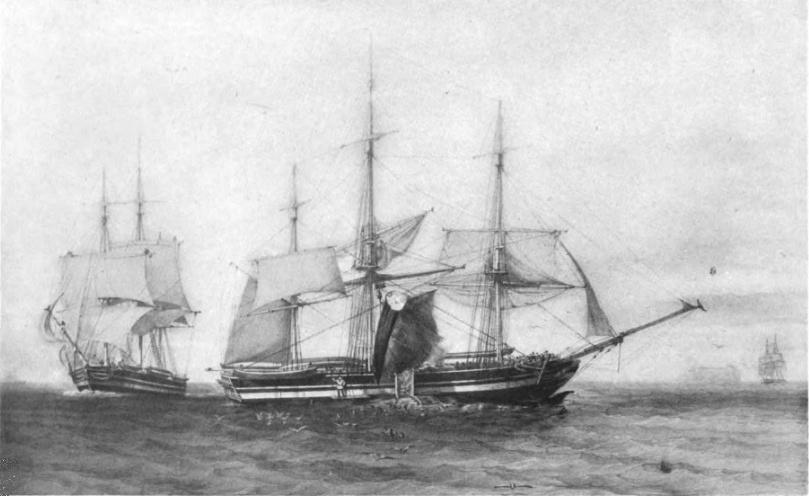

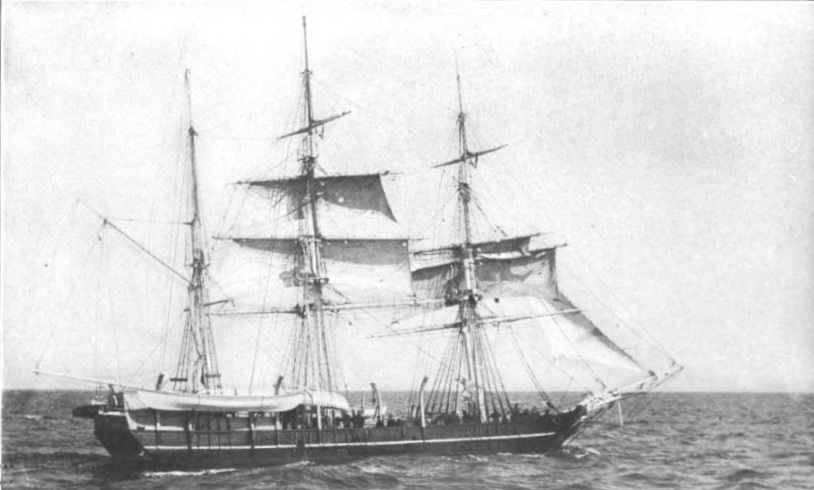

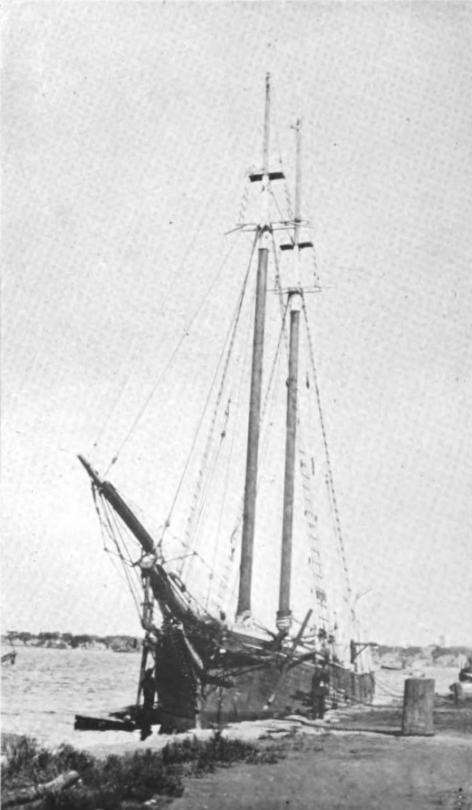

Out of Commission. Bark Charles W. Morgan, Built in 1841. One of New Bedford's famous old whalers and now, 1915, fitting out for a voyage to the South Shetlands for sea elephant oil. |

THE REAL STORY

|

|

Copyright, 1916 By

D. APPLETON AND COMPANY Printed in the United States of America |

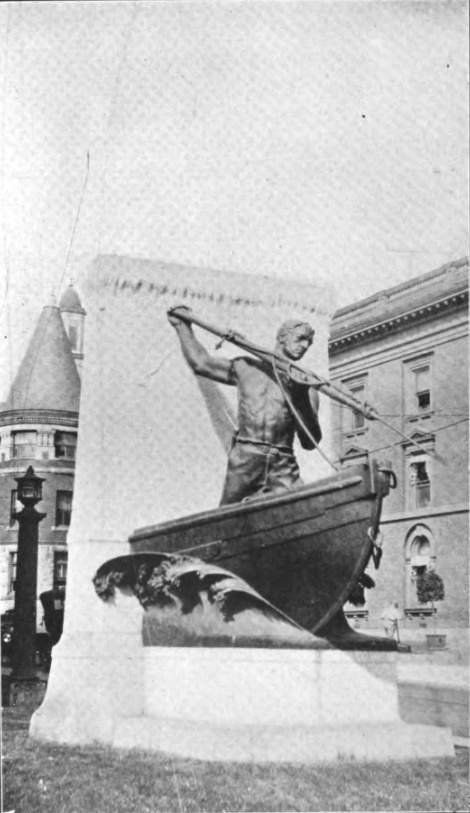

INTRODUCTIONThere is always a fascination about the lives of men who follow the sea and of all those who "go down to the sea in ships" the bravest, most adventurous and hardiest were the Yankee whalemen. Many stories of whalers and whaling have been written, but in nearly every case a glamour of romance and mystery has been woven about the whalemen of fiction and a false idea has been created as to their lives, their calling and their voyages. But no fiction has ever been written which does justice to the indomitable courage, the reckless daring, the terrific dangers, the unspeakable hardships, the heart breaking labor, the terrible privations, the inhuman brutality, and the sublime heroism which were all in the day's work of the whalemen. To the Yankee whalers our country owes a debt of gratitude which can never be repaid and no man is more worthy of a niche in America's Hall of Fame or a prominent place in our history than the weather-beaten, old-time whaler of New England. For more than two centuries they scoured the seven seas and built the prosperity and progress of New England by pitting their lives against those of the mighty monsters of the deep. But the very wealth, progress and civilization which they helped to estab- v

|

lish resulted in their downfall, until today the Yankee whaler is a figure of the past. This book has been written to give a true and unvarnished idea of the whalemen's lives, their adventures and hardships, the means by which their quarry was sought and captured, their vessels and their voyages. It is intended not as a history of the whaling industry nor as a technical description of whaling methods but rather as a narrative of a whaleman's life embodying details of the chase, the vessels and their equipment, the whales and their habits, the dangers incident to whaling, the labors and privations of every day occurrence, the voyages made and true stories of the sea. Volumes might be written on the subject and much would still be left unrecorded, for whaling was a profession built up by many generations and by actual experience and the mass of technical details connected with the occupation is overwhelming. Only the more important, interesting or salient features and incidents have been included in this work and if it leads to a better and more sympathetic knowledge of the whalers, a realization of what we owe them, a truer insight into their lives, and at the same time interests the reader the author's aim will be accomplished. To my many friends in New Bedford I wish to express my gratitude for innumerable courtesies and much invaluable aid without which the work of writing this book would have been a difficult task indeed. vi

|

Particularly am I indebted to Mr. Frank Wood and to Mr. Pemberton H. Nye; to the former for permitting free access to the priceless records and wonderful collections of the Old Dartmouth Historical Society and to the latter for advice, information and suggestions such as could only have been obtained from one who has actually taken part in the scenes described. vii

|

CONTENTSCHAPTER

ix

|

x

|

xi

|

xiv

|

xv

|

THE REAL STORY,

|

|

'Twas a love of adventure, a longing for gold, And a hardened desire to roam Tempted me far away o'er the watery world, Far away from my kindred and home. – WHALER'S SONG. |

Few of us realize how much we owe the whalers, the prominent part they played in our history, the prosperity and wealth they brought to the infant Republic, or the influence their rough and ready lives had upon the civilization, exploration and commerce of the globe.

The first time the Stars and Stripes were unfurled in a British port they snapped in the wind of the English Channel at a whaler's masthead. The first time Old Glory was seen on the western coast of South America it soared

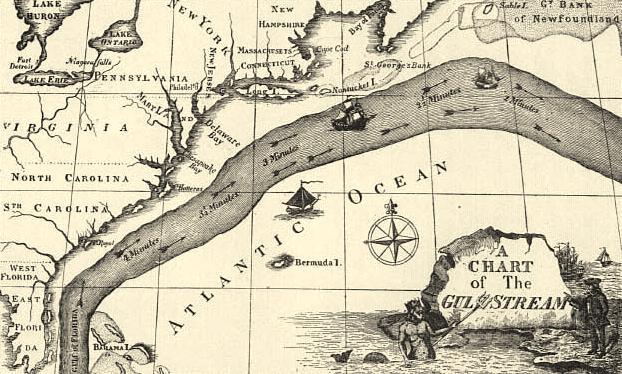

aloft to a whaleship's truck, and far and wide, to the desolate Arctic, to the palm-fringed islands of the tropics, to the coral shores of the South Seas – to every land washed by the waves of any ocean – the banner of our land was carried by the Yankee whaling skippers. No sea was too broad for the whalers to cross; no land too remote, too wild or too forbidding for them to visit. The crushing ice-floes of the Arctic, the vast desolation of the Antarctic, the uncharted reefs of the Pacific or the cannibals of Polynesia held no terrors for the weather-beaten whalemen of New Bedford or Nantucket. In many a new-found land, on many an unknown island, the naked savages saw white men for the first time when a bluff-bowed, dingy-sailed whaleship dropped anchor off their shores. Nearly half a century before Paul Revere made his famous ride the hardy whalemen of Massachusetts had sought their quarry in the waters north of Davis Straits. It was a Nantucket whaleman, Captain Folger, who first sketched the Gulf Stream and its course, and this rude drawing, engraved for Benjamin Franklin, revolutionized the commerce between Europe and America. Ten years before the first shot of the Revolution 2

|

was fired whalemen pushed through the Arctic Ocean and sought the Northwest passage and within twelve years after the Declaration of Independence the whaling ship Penelope of Nantucket had cruised in waters farther north than were reached by any vessel for a century later.

Franklin's Map of the Gulf Stream Made from a Whaleman's Sketch. By 1848 the bark Superior of Gay Head had penetrated Behring Straits and three years later the Saratoga of New Bedford reached 71º 40' north, fifteen miles nearer the pole than had been attained by the exploring ship Blossom. It was the reports of whalers that led Wilkes on his famous explorations 3

|

and years before Perry opened the doors of Japan to commerce whalers had visited its shores, had cruised in its waters and one whaleman had lived among the Japanese and had taught them English. Ever the first to penetrate unknown seas and to visit new lands, the whalers were the pioneers of exploration and blazed a trail for commerce, civilization and Christianity to follow. Knowing no fear, laughing at danger, self-reliant and accustomed to fighting against overwhelming odds, the whalemen performed many a deed of heroism and bravery of which the world never hears. It was the crews of the whaling ships Magnolia and Edward of New Bedford that saved the garrison of San Jose, California, from annihilation in 1846. When the government buildings burned at Honolulu it was whalemen who saved the town, and when wars broke out and their country needed fighting men, the whalers were among the first to respond to the call to arms and much of our success in naval battles of the past was due to the men who had learned seamanship, courage and reckless daring in the hard school of whaling. And how would it have fared with the 4

|

The Whalemen's Bethel and Seamen's Home at New Bedford. |

American colonies if it had not been for the whalemen? Hardly had the Pilgrims landed on Massachusetts' shores when the whale fishery was born and Cape Cod was settled mainly because of the abundance of whales in its waters. By 1639 the whales had become one of Massachusetts' greatest sources of revenue, and within the next two years Long Island was settled by whalers. So important did the colonists find this industry that in 1644 the town of Southampton was divided into four wards of eleven people each whose duty was to secure and cut up the whales that came ashore. At that time no ships had set forth in quest of whales and the whalemen depended upon those which could be captured from small boats and it was not until 1688 that the first whaleship set forth on a true whaling cruise. In August of that year the Brigantine Happy Return, Timotheus Vanderuen, master, sailed out of Boston harbor bound for the Bahamas and Florida in search of sperm whales; the first of the fleet which later dotted the broad oceans of the world and made the name of New England famous in every land. Within a dozen years the sails of sloops, brigs and schooners from Nantucket and other 5

|

Massachusetts towns were spread to the winds of the Atlantic from the Arctic circle to the equator. Laden deep with oil the ships returned, and into the coffers of the little New England towns flowed a steady stream of gold. Many of these coast towns, almost unknown to the people of the neighboring states, became famous throughout the world, and in many a distant land and to many a strange people the name of New Bedford, New London, Gay Head, Nantucket, Bristol or Sag Harbor was more familiar than New York, Washington or Boston. Upon the whalers such ports depended for their very existence, and to their hardy whaling sons they owe the foundation of their present prosperity and standing. New Bedford in particular was built up by the whaling industry, and the skill, hardihood and daring of its whalemen brought fame and fortune to the town and made its name known in every seaport of the globe as the greatest of all whaling ports. Although New Bedford no longer depends upon the whaling industry and has become a busy manufacturing town, yet much of the old atmosphere, many of the old landmarks and a great deal of interest still remain. The 6

|

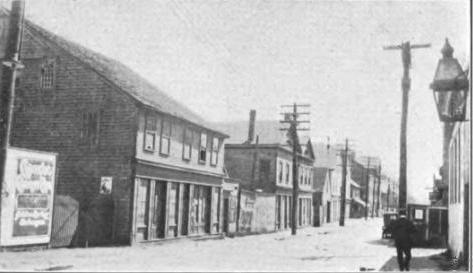

Where the Whalemen Lived. Old boarding-houses and sharks' stores in New Bedford. |

one-time whalers' boarding-houses and dance-halls, belonging to the Hetty Green property, still stand much as in days gone by and near them are the old storehouses where formerly vast quantities – veritable fortunes – of whale-bone were kept. The famous seamen's Bethel and sailors' home stands high above the neighboring buildings upon a little knoll, and in the Bethel one may read many cenotaphs erected to the memory of whalemen who met death during their long and dangerous cruises. Some of these are very quaint, and in stilted, old-fashioned phraseology relate thrilling tragedies of the sea in a few terse sentences as, for example, the following, which are two of the most noteworthy:

ERECTED

BY THE OFFICERS AND CREW OF THE BARK A. R. TUCKER OF NEW BEDFORD TO THE MEMORY OF CHAS. H. PETTY OF WESTPORT, MASS. WHO DIED DEC. 14TH, 1863 IN THE 18TH YR. OF HIS AGE. HIS DEATH OCCURRED IN 9 HRS. AFTER BEING BITTEN BY A SHARK WHILE BATHING NEAR THE SHIP HE WAS BURIED BY HIS SHIPMATES ON THE ISLAND OF DE LOSS, NEAR THE COAST OF AFRICA 7

|

IN MEMORY OF

CAPT. WM. SWAIN ASSOCIATE MASTER OF THE CHRISTOPHER MITCHELL OF NANTUCKET. THIS WORTHY MAN AFTER FASTENING TO A WHALE WAS CARRIED OVERBOARD BY THE LINE AND DROWNED MAY 19TH, 1844 IN THE 49TH YR. OF HIS AGE BE YE ALSO READY, FOR IN SUCH AN HOUR AS YE THINK NOT THE SON OF MAN COMETH Many another tablet records a sudden death by violence, and yet not one whalemen in a thousand who found a grave in the vast depths of the oceans had friends or relatives to place a tablet to his memory in the little Bethel of his home port. Only captains and officers were so honored, the common whaleman, the men who toiled and slaved and endured, were not worth recording; a bit of old sail was their winding sheet and coffin, the deep sea was their grave, and a line in a log-book their only epitaph. They died as they lived; unknown, unhonored and unsung, mere units in the vast army of whalemen whose duty was to obey, who faced death unflinchingly and with a laugh or a curse; rough, 8

|

|

|

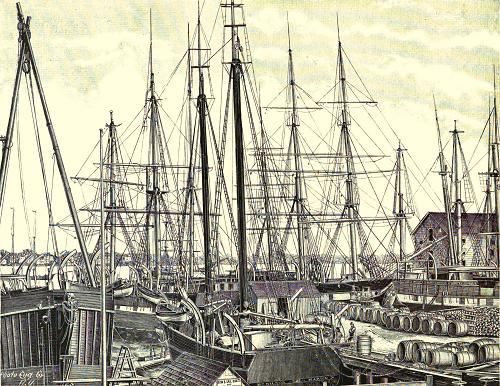

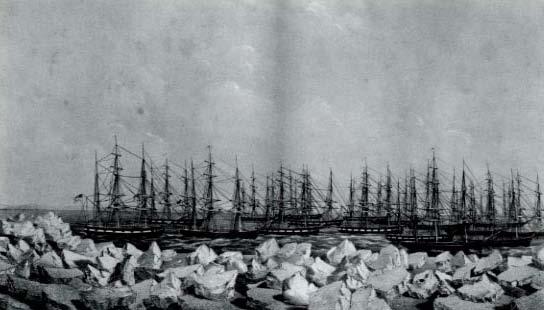

vicious, brutal perhaps, but as brave as any men who ever trod a ship's deck. From the windows of the Bethel and the home the seamen could look down upon the busy wharves along the waterfront and across the harbor to Fairhaven, on the farther shore, with a forest of masts and spars outlined against the water and the sky. To-day the museum of the Old Dartmouth Historical Society obstructs the view and the forest of masts has disappeared. Along the docks a few schooners and perchance a brig or bark may lie moored; a few great casks of oil may be piled upon the wharves, and across the harbor a few famous old ships may be seen, forsaken, dismantled and weather-beaten where they lie in the slips at the foot of shady streets and lanes. Many a relic of the bygone days, when whaling was at its zenith, may still be seen in Fairhaven – such as the old candle factories, the blacksmith shops where lances, harpoons and other fittings were made and the boat yards where the whaleboats were built and the ships repaired. It is in New Bedford itself, however, that one may obtain a true insight as to the whalers 9

|

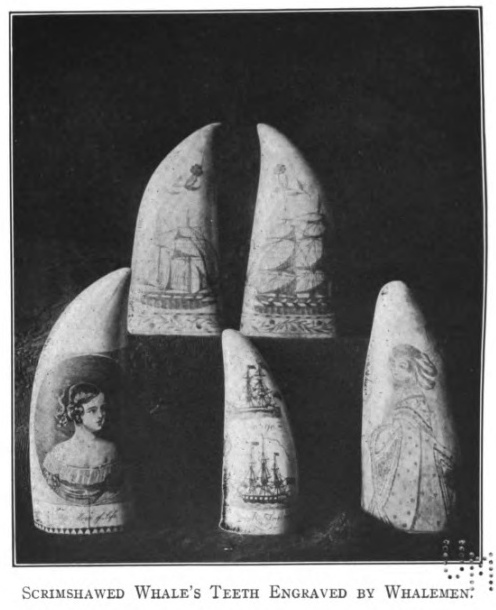

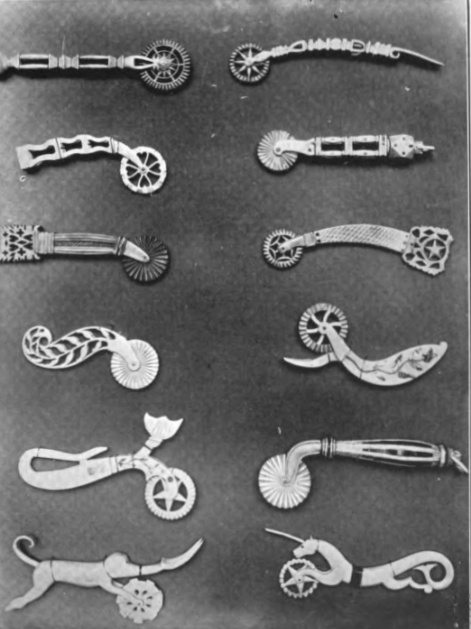

and their calling and in the building of the Historical Society on Water Street is the most complete whaling museum in all the world. Here are hundreds of beautifully wrought ornaments, implements and utensils carved from whales' teeth and walrus' tusks by the whalemen during spare moments. Scores of whales' teeth engraved or "scrimshawed." by the whalers are also shown; there are models of whaling vessels made by the men themselves; letters written by them; paintings and drawings of famous vessels; priceless log-books and journals of the whalers as well as all the forms of lances, spades, guns and harpoons used in whaling; house-flags and figure-heads of famous ships, and tools and machines used in cutting blubber and trying out oil. A real whaleboat, which has seen active service, complete with all its equipment, occupies a prominent place in one room and best of all is a half-size model of a whaling ship, built to absolute scale and perfect in its every detail. 10

|

CHAPTER IIWHALES AND THEIR WAYS

In order to obtain an intelligent idea of whaling, to appreciate the perils and hardships of the calling and to understand the story of the whaler it is necessary to know something of the various kinds of whales and their habits, for there were many forms of whaling and the methods employed, the implements and weapons used and the dangers faced, depended upon the species of whale hunted. A great many people think of whales as fish but in reality they are no more fish than are horses and cows. Whales and all their relatives, such as porpoises, grampuses, and narwhals, are mammals – warm-blooded creatures which bring forth their young alive and suckle 11

|

their offspring like any four-footed land mammal. They also possess lungs and breathe air and are compelled to rise to the surface of the sea to breathe or "blow," and it is the air, warmed from their lungs and expelled as they take a fresh breath, which forms the little puff of vapor that often betrays a whale's presence. We often hear of whales "spouting" but in a strict sense they do not spout nor discharge water from their nose, although when wounded in a vital spot their breath is mixed with blood and they are said to "spout blood." Unlike whales, true fish are cold-blooded and lay eggs and instead of having lungs they are provided with gills which enable them to separate the oxygen from the water without coming to the surface. The confusion of whales with fish arises through the fact that whales are fish-like in form, are legless and hairless and live in the sea; but manatees and dugongs are hairless and have no true legs, and many seals also lack legs and live most of the time in the water and yet no one would dream of calling a seal a fish. As a matter of fact the so-called "fins" or 12

|

flippers of whales are really front legs which have been transformed to swimming organs, and if a whale's skeleton is examined we will find small bones which represent the hind legs of the whale's remote ancestors. Whalemen often speak of "taking a fish" of so many barrels and we frequently hear the term "whale fishery," but so we hear also of the "seal fishery," the "clam fishery," etc., and when a whaleman speaks of a "fish"

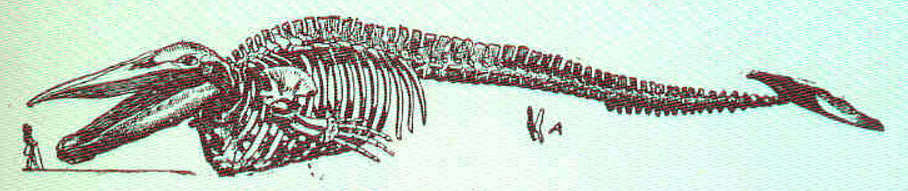

Skeleton of Right Whale Showing Comparative Size of Man. A – bones which represent legs. he merely uses the vernacular and does not use the term through ignorance, for every whaleman knows full well that whales are mammals and not fishes. There are a great many varieties of whales recognized by naturalists, but to the whalemen there were only six kinds of real whales. These were the sperm whale, the right whale, the bowhead, the humpback, the sulphur-bottom and the finback. 13

|

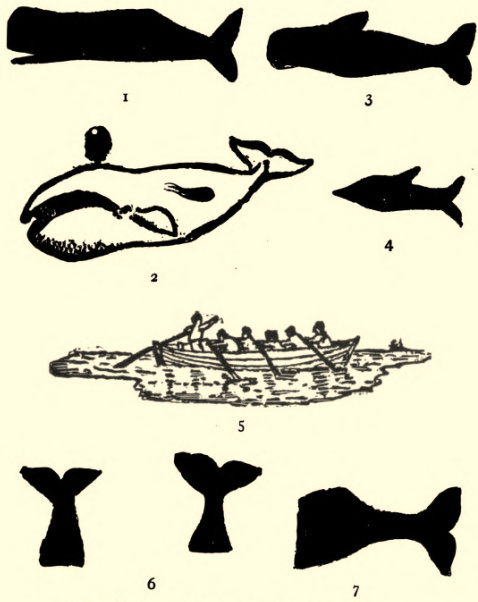

In addition to these, there were the various porpoises, the grampus or blackfish, the narwhal or unicorn whale and the beluga or white whale, all of which were at times captured. Each variety of the true whales has haunts

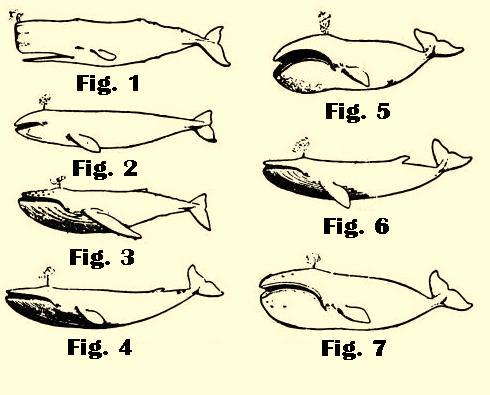

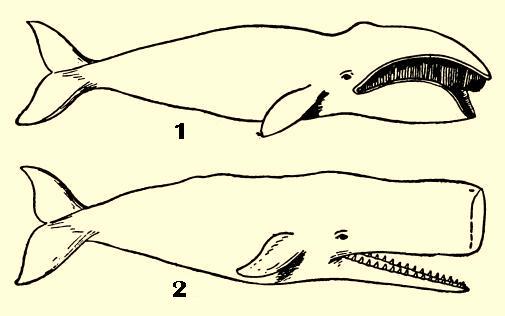

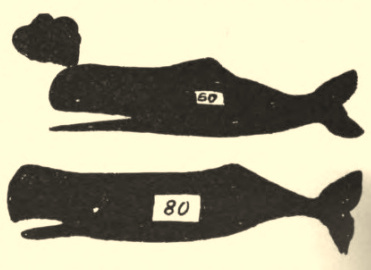

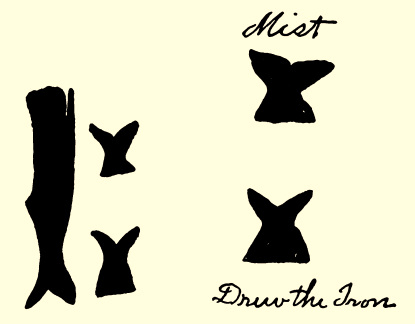

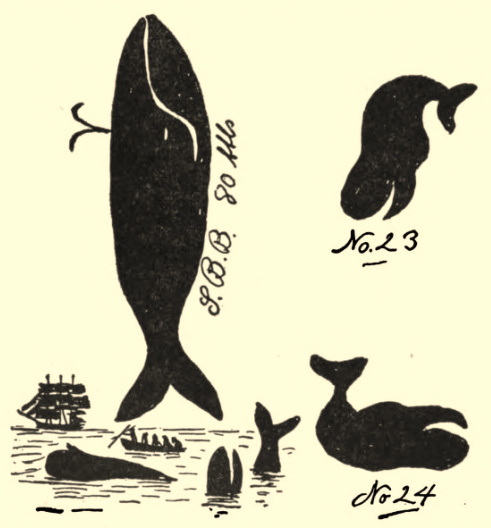

Various Kinds of Whales. 1 – Sperm whale. 2 – California gray whale. 3 – Humpback whale. 4 – Sulphur-bottom whale. 5 – Bowhead. 6 – Finback whale. 7 – Right whale. and habits of its own and each furnishes oil and other products of distinct kinds and different values. Of all the true whales the sperm whales and right whales were the most valuable and were the ones most widely sought. The right 14

|

whales and bowheads are inhabitants of arctic and antarctic waters and while the two are distinct, their habits, products, and the methods of hunting them are so similar that both may be considered together, the main difference being that the true right whales were hunted in the northern Pacific, Behring Sea and neighboring waters, whereas bowheads were denizens of the Arctic Ocean and Hudson Bay, while the antarctic right whale was found in the waters of the antarctic seas.* The right whales and bowheads furnish oil and whalebone, the latter article formerly being among the most valuable of whale products, while the oil is not nearly as valuable as that obtained from the sperm whale. The so-called "bone" of the right whale is in reality a hornlike material growing from the upper jaw of the whale in the form of a thick, flexible fringe. The lower jaw is very large and is shaped like an immense ladle or spoon and has no teeth. To the right whales * The Biscay whale, small species of right whale, is a native of temperate and subtropical seas. This is the whale formerly abundant on the New England coast and which the early whalers of New England hunted. It is rare today, although specimens occasionally are captured on the southern shore of Long Island. 15

|

and bowheads the whalebone or "baleen" serves as a strainer and is essential to the peculiar methods of feeding of these whales. Opening his mouth, the right whale swims through the water until his great trough-like lower jaws is filled with small fish and marine

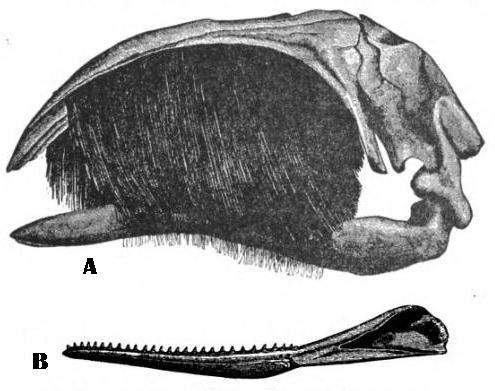

1 – Right Whale to Show Whalebone. 2 – Sperm Whale Showing Teeth. animals. Then, closing his mouth the whale forces out the sea-water through the fringe of whalebone, thus leaving the shrimps and other creatures it contained within his mouth, where they are confined by the gigantic strainer of baleen. Owing to the enormous size of his jaws and the position of his eyes the right whale cannot 16

|

see ahead of him, and owing to his habits, it is not necessary that he should, for his prey consists wholly of minute creatures, many of which are almost microscopic in size, and he trusts to luck in gathering everything

A – Jaws of Right Whale Showing Whalebone. B – Lower Jaw of Sperm Whale Showing Teeth. within reach as he swims along like a mammoth scoop-net. As he has no teeth and as his jaws are useless as weapons of defense, nature has given him a wonderfully powerful and agile tail, and the right whale can sweep his tail, or 17

|

"flukes," as the whalers call it, from eye to eye in a great half-circle and woe to any boat or enemy that comes within reach of this ponderous, thrashing mass of bone, flesh and sinew. The sperm whales, of which there are several varieties, are all inhabitants of the broad oceans of temperate and tropical latitudes and are very different in habits, structure and appearance from the right whales and bowheads of the cold seas. The upper jaw of the sperm whale has no whalebone and no teeth, but the lower jaw, which is slender and sharp, bears a row of pointed, conical, white teeth as hard as ivory and these are as necessary to the sperm whale as the baleen to the right whale and bowheads. Whereas the right whales swim along at or near the surface and scoop up tiny marine animals for their food, the sperm whales seek their food at the bottom of the sea and dive to great depths to secure the strange and powerful animals which form their diet. These are the giant cuttlefish or squids and many a battle royal must take place between the sperm whales and their enormous victims which lurk upon the floor of the ocean. 18

|

With their sharp teeth and active jaws the whales seize the great squids, tear them from their hold upon the rocks or bottom and bite them into bits, for the sperm whale's throat is very small – scarcely large enough to admit a man's fist – and only small morsels can be swallowed at a time. Of course a great many of the squids secured by the whales are very small and offer but feeble resistance

The Sperm Whale's Food; Giant Squid. to their mammoth enemies, but others are of titanic size and must give the whales a hard tussle indeed. No doubt the whales at times fall victims to their own prey, for the squids grow to a length of forty or fifty feet with ten long, flexible, snake-like tentacles armed with hundreds of great suckers. Moreover the squids possess enormous strength and are very tenacious of life and if such a monster once secured 19

|

a good hold upon a whale he might well resist every effort of the latter long enough to drown the whale. That such tragedies of the deep actually occur is beyond question, for dead sperm whales have been found floating, with no sign of injury or disease save the marks of a submarine battle with the squids, and no doubt many of those which are overcome by their prey never rise to the surface of the sea, but are actually devoured by the very creatures they sought to secure for their own meals. Whalers have known that the sperm whales fed upon cuttlefish for a long time but no one dreamed of the size of the giant squids of the ocean's depths until dead ones were cast upon the beaches of Newfoundland and pieces of their enormous arms were discovered in the stomachs of sperm whales. Scientists who were interested in the study of these strange monsters of the deep found many of their most interesting specimens in the stomachs of sperm whales and the Prince of Monaco even fitted out an expedition to hunt and kill sperm whales for the sake of the rare specimens of cuttlefish which could be obtained by cutting open the whales. 20

|

It is owing to their fondness for the squids that the sperm whales produce the rare and valuable substance known as "ambergris." This is a light, porous, greasy material which is at times found floating upon the surface of the sea or cast upon beaches and which is used in making perfumes, not for its scent, but because it possesses the curious property of retaining or absorbing odors to a wonderful degree. It is worth more than its weight in gold and often the whaler who secured a few lumps of ambergris made more money from his find than from all the oil obtained on a long cruise. In former times there was a great deal of mystery surrounding the origin of this strange substance, but bits of cuttlefish beaks were often found in it and it is now known to be a sort of disease growth in the whale's intestines, caused by an accumulation of indigestible portions of the squids, and large quantities are at times secured by dissecting the whales.1 * Very few records have ever been published showing the actual quantities of ambergris obtained by whalers. The following is an official record of ambergris "catches" for a period of seventy-three years: RECORDS OF AMBERGRIS CATCHES

21

|

Owing to their habit of feeding and the necessity of seeing their prey, sperm whales' eyes are so placed that they can see any object in front of their heads or to either side, but they cannot see to the rear. Unlike the right whales the sperm whales have a terrible weapon of defense in their tooth-armed lower

22

|

jaw which is capable of biting a whaleboat in two and chewing it into matchwood, and while their great flukes are very powerful they are far less to be dreaded than those of the right whales. "Beware of a sperm's jaw and a right whale's flukes" is a whaler's maxim always borne in mind and taking advantage of this and the

23

|

fact that one species can see ahead and the other behind, the whalers strive to approach sperm whales from the rear and right whales directly from the front. Although the sperm whale has no whalebone, yet its oil is far more valuable than that obtained from the right whales and bowheads and, in addition, this creature furnishes the substance known as "spermaceti," which was formerly among the most valuable of all whale products. The spermaceti is a clear, limpid, oil-like liquid contained in a great cavity in the sperm whale's head and which is known as the "case"; but upon exposure to the air the spermaceti hardens rapidly and becomes a semi-opaque, wax-like material. It was formerly used in making the best grades of candles and in other arts and manufactures, but has now been largely superseded by stearine and paraffin, just as whale oil has been replaced by petroleum and kerosene. Very different from the sperm whales, right whales and bowheads are the humpbacks, finbacks and sulphur-bottoms. The finbacks and sulphur-bottoms gave comparatively little oil and bone of inferior quality and were not 24

|

considered worth taking by the old-time whalers, but today the finback-whale fishery forms a very important industry in japan, Scandinavia and on our Northwest coast. One reason that the old whalers left these whales alone was because of the difficulty in securing them. They were among the largest, if not the very largest, of all whales; they were very powerful, rapid swimmers; they were very alert and wary, dangerous when "struck" and they often sank when killed. To-day steam whaleships, darting-guns and bombs have made the hunting of finbacks easy and they are kept from sinking by forcing compressed air into their bodies. The humpbacks, however, were often hunted by the old Yankee whalers and while their oil was inferior to that of the sperm whales they were well worth capturing. As the humpbacks frequented the bays and inlets of the Pacific and Indian Oceans during their breeding season and lived in shallow waters when the cows were accompanied by their calves, the whalers sought them on the coasts of South America, Africa, Madagascar and the islands of the South Seas. This was known as "bay whaling," and compared to arctic or antarctic 25

|

whaling, or sperm whaling on the open ocean, it was easy, simple and comparatively safe work. Although whales were always the main object of the whalers, yet anything which would give oil was taken when opportunity offered and many casks of grampus and porpoise oil were brought home from whaling cruises. Porpoises or "dolphins," as they are often incorrectly called, are found in every sea and while there are many species they are all similar in appearance or habits. Their oil is used for lubricating watches, mathematical instruments and fine machinery and brings a high price, but most of it is obtained from the porpoise fisheries of the Carolina coast and from the Passamoquoddy Indians of Eastport, Maine, who hunt porpoises in canoes. Porpoises are too small, too active and too much trouble to attract the whalers and it was only now and then that they were captured. Somewhat similar to the porpoises, but much larger and forming a sort of connecting link between them and the true whales, is the grampus, more often known as "blackfish" to the whalers. These creatures go in large schools and are far more sluggish than por- 26

|

poises and yield a much larger amount of oil. They were often killed by the whalemen, as were also the "white whales" or belugas, a small species of whale, light gray in color and common in the Gulf of St. Lawrence and neighboring waters. Still another whale-like creature which the

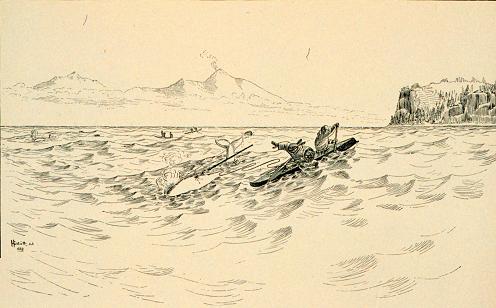

Eskimos Capturing White Whales. whalers at times obtained was the narwhal, or "unicorn whale," a curious, spotted mammal somewhat resembling a porpoise or grampus but with a long, pointed hor " or tooth of spirally grooved ivory projecting from the upper jaw, like a great, white pole. The narwhal is an inhabitant of arctic seas, and here in the Far North the whalers also hunted many other animals, such as walrus, seals, bears, musk- 27

|

oxen or in fact anything which produced blubber and oil, which bore hides or skins of value, or which furnished meat which was edible. Indeed some of the arctic whalers were more trappers, hunters and traders than true whalers and found that skins and furs obtained by the friendly Eskimos were more profitable than the whale oil and bone which they ostensibly set out to secure. Many other whalers sailed to the forbidding and desolate islands of the Anarctic in search: of seals and sea-elephants and at times they spent many months on Kerguelan, South Georgia and other uninhabited, barren and cold spots, while- their ships sailed away to Cape Town for repairs and to refit. The great sea-elephants furnished an enormous quantity of oil and were so stupid and so easily killed that they were almost exterminated by the whalers in many places, but hunting such helpless creatures on land was not true whaling, and the methods by which the slaughter was carried on and the life of the whalers on shore or ice, has nothing to do with their life on shipboard, and seals, sea-elephants or even porpoises deserve no place in the story of the whaler. 28

|

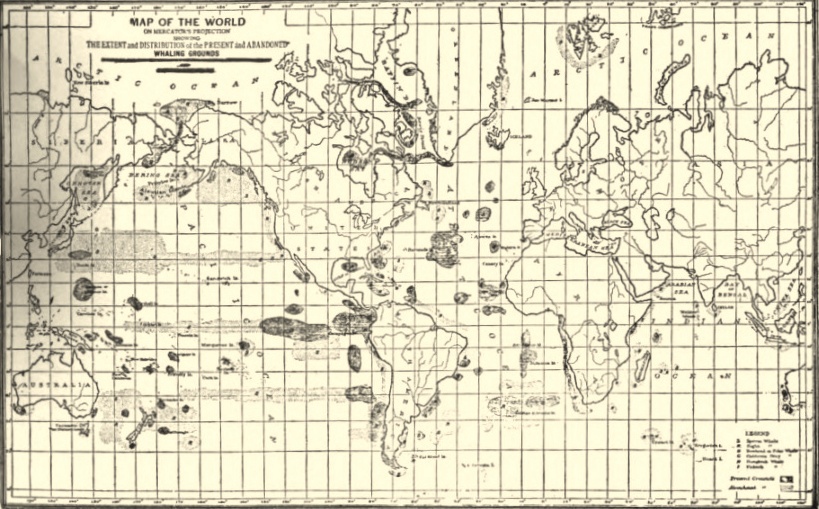

CHAPTER IIIHOW THE WHALES WERE CAUGHT

As already mentioned, the method used in whaling, the outfits required, and the "grounds" to be sought, varied according to the kind of whales to be hunted, but the whalers and whaleships did not confine themselves to any one class of whales, even on a single cruise. Many old whalers were sperm whalers all their lives and never hunted or saw either bowheads or right whales; others never whaled on the open Atlantic or Pacific but sought only the right whales and bowheads of the arctic seas, while some who hunted right whales never killed a bowhead and vice versa. But as a rule "all was fish that came to a whaleman's net," figuratively speaking, and whalemen set sail from New Bedford or other 29

|

Where the Whalers Cruised. 30

|

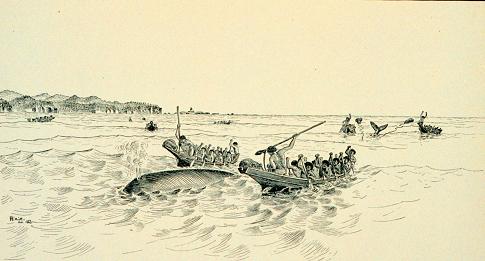

ports bound for "any ocean," and before their return, at the end of three, four or five years, hunted sperm whales up and down the wide Atlantic, rounded Cape Horn and hunted whales on the western coast of South America and pushed far into the ice-floes of the Kamschatka seas in search of bowheads. Then, if not filled up, a course was followed down the shores of Japan and through the China Sea; the smoke from their try-works darkened the skies and fouled the spice-laden airs of the Malay Archipelago and Polynesia; they killed humpbacks in the bays of West Africa and Madagascar, and perchance called at Kerguelan ere hoisting topsails for home after thus circumnavigating the globe. In the early days of New England all the whaling was "shore whaling" by means of small boats and all the whales attacked and captured were those which approached close to the shores and could be seen from the land. The whales thus obtained were the Biscay whales, a small species of right whale and which has been almost exterminated. The shore whaling was carried on by means of harpoons and lances and a large proportion of the whale men were native American Indians. 31

|

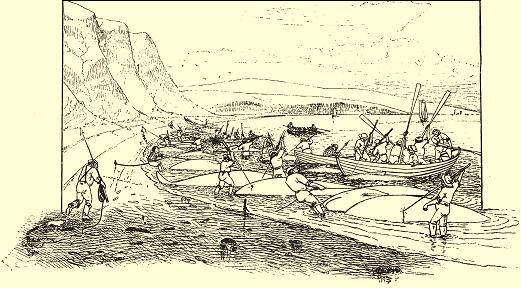

In fact the red men were so essential to the success of the early whalers that laws were passed exempting them from many taxes and legal penalties, and the Indian whalemen who enlisted in the army were discharged at the beginning of the whaling season to enable

Shore Whaling On Cape Cod. Capturing a school of blackfish or grampus. them to take part in the fisheries. Between the first of November and the fifteenth of April, Indians who were whalers were free from lawsuits, arrest for debt or petty offenses, and from military duties, and even after whaling vessels made long sea voyages and shore whaling was practically abandoned the 32

|

Gay Head and Long Island Indians formed a good portion of the whaling crews. The first sperm whale recorded from Nantucket was taken in 1712, when a whaler, Christopher Hussey, was blown off shore and found himself amid a school of sperm whales. One of these he succeeded in capturing and the gale abating, he towed his prize ashore. This seemingly trivial event was fraught with the greatest importance and led to the establishment of the vast whaling industry and the countless whaleships which made Nantucket famous throughout the world and which paved the way for the wealth and prosperity of other New England town's that depended upon the whalers for their greatest revenue. The first Nantucket whaling vessels were small, thirty-ton sloops fitted for cruises of a few weeks' duration and after capturing one whale they returned to port. Three years after Christopher Hussey discovered the sperm whales, the value of sperm oil obtained by the Nantucket whalers amounted to over five thousand dollars each season, and within a dozen years a fleet of twenty-five or thirty vessels was engaged in sperm whaling, Nantucket's annual capture of oil was valued at 33

|

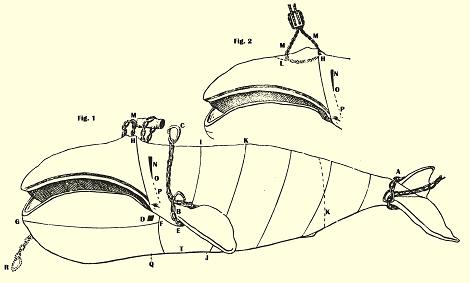

over twenty thousand dollars and the little sea-girt Massachusetts island led the world as a whaling port. These early Nantucket whaleships were very different in size and equipment from the whalers of later years, their methods, implements and appliances were crude, and it was not until 1761 that the oil was even tried out at sea. Once it was discovered that vessels could capture whales, could try out the oil and could store it in casks without returning to port, true deep-water whaling commenced and from that time on, shore whaling was practically abandoned and ocean whaling became an established industry. From the small sloops of early days the vessels were increased in size until large barks, ships and brigs were in almost universal use and were fitted out for cruises of several years' duration. But the earliest whalers had accomplished much and had adopted the best tools, weapons and implements adapted to the capture and cutting up of whales and the later whalers found it difficult to improve upon the equipment of their predecessors. For capturing the whales, harpoons or "irons," 34

|

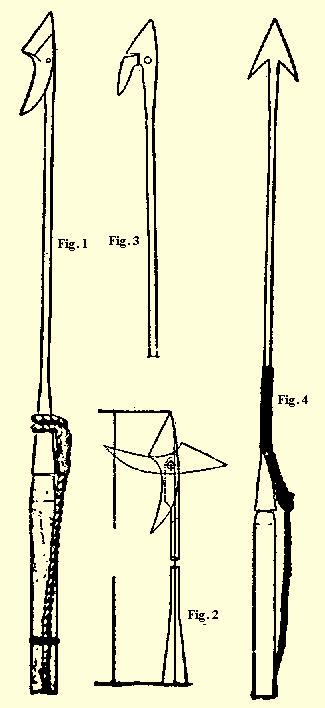

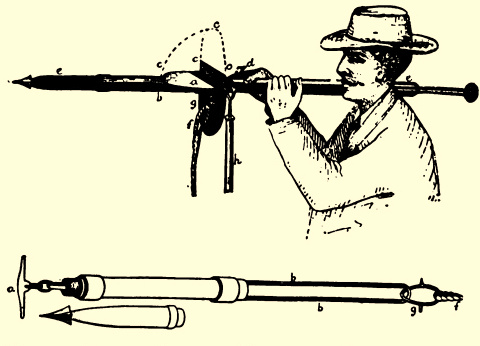

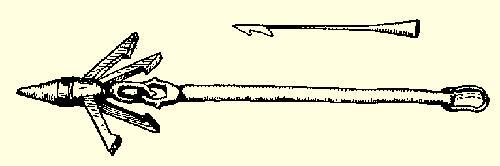

as the whalemen call them, were used. These were home-made in blacksmith shops and were often rough and crude. The "iron" consists

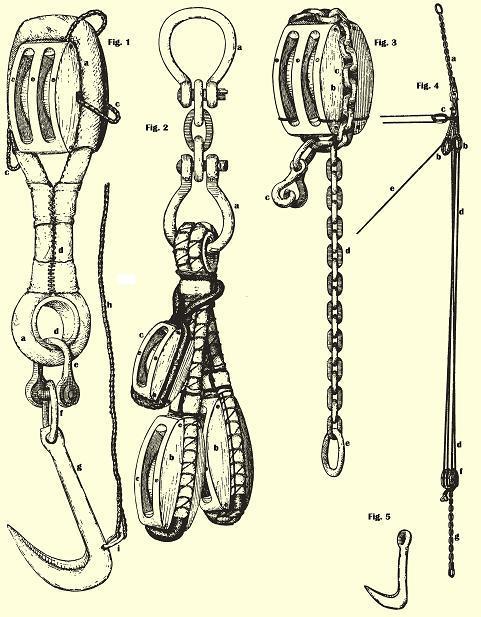

Harpoons or "Irons" 1 – Style in general use; 2 – How iron "toggles" when in whale; 3 – Hinged toggle-iron; 4 – Iron used in striking porpoises, etc. of a slender shank about three feet in length with one end forming a conical recess and the other bearing a pivoted, more or less triangular, 35

|

blade. To the conical end a heavy oak or hickory pole, six feet in length, is fastened and just below the conical ferrule a stout rope is attached by means of an eye-splice and turn. This line is seized, by marline, at two points on the wooden pole and another eye-splice is formed in the extreme end of the rope. When in use the rope, or line, which is coiled in tubs in the whaleboat, is bent on to the latter eye-splice. The iron is thrown or "darted" into the whale and the pivoted tip, turning at right angles to the shaft, prevents it from being withdrawn and the whale is thus held by the rope attached to the iron shank, and not to the wooden pole. Many people are under the impression that the iron, or harpoon, is a light, javelin-like affair and is thrown for considerable distances, but as a matter of fact it is a tremendously heavy, clumsy and cumbersome implement and must be "hove" by both hands of the whaleman and cannot be thrown more than fifteen or twenty feet. The great weight of the harpoon and its stout hickory staff is necessary in order to make the iron penetrate the skin and thick blubber of the whale, and it would require a veritable Hercules to poise one of these irons in one hand and 36

|

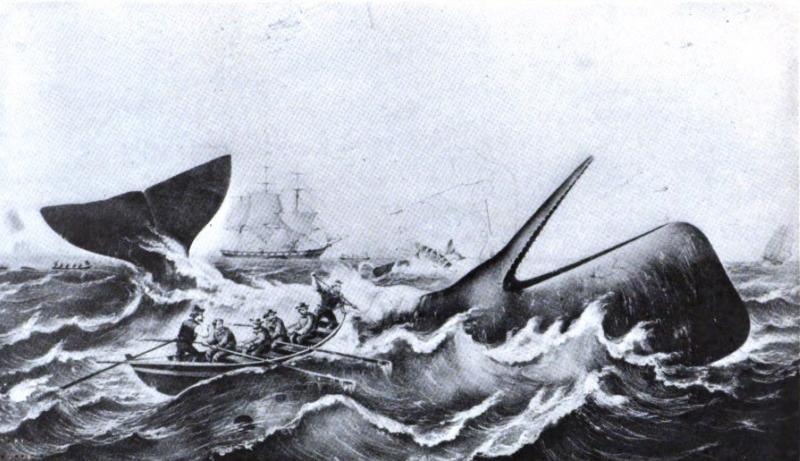

throw it like a javelin for forty or fifty feet, as often depicted in fanciful illustrations of whaling. The harpoon or iron is not intended to kill the whale, but merely to secure a hold upon him and to prevent him from escaping from the boat, but even when "struck" whales often succeed in getting away. The line may break, the iron may pull out or "draw" or may even become twisted and broken off, or the whale may sound or dive beyond the limit of the line and thus compel the whalemen to cut loose in order to save themselves from being drawn below the surface of the sea. Then again the whale may roll over and over, winding the line about his body; he may travel so far that the boat is in danger of being towed out of sight of the ship, or he may turn and ram the boat. If all goes well and the iron holds fast the boat is finally drawn close alongside the stricken monster and he is killed by means of a lance. The lance formerly used consisted of a slender, iron shank, five or six feet long; with a sharp-pointed, keen-edged, spear-shaped blade. The other end of the shank was conical, like that of the harpoon, and was fitted to a heavy pole about six feet in length. In order to use this 37

|

instrument the boat had to be hauled within a few feet of the wounded whale and the lance was then driven into his vitals by pushing upon its haft. This was the most dangerous part of the hunt. Imagine running a frail boat within arm's length of a ninety-foot, wounded whale and actually

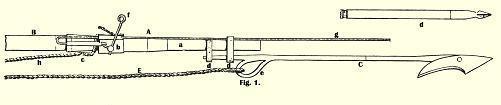

Darting Gun and Bomb-Lance Combined.

shoving the lance into his flesh! No wonder many men were killed and injured, numerous boats smashed and many whales lost when accomplishing such a feat. But in later years the bomb-lance largely superseded the old-time weapon and made killing the whales less perilous and more certain. The bomb-lance most commonly used con- 38

|

sisted of an iron or harpoon attached to a pole and beside it a gun-like arrangement containing

Darting and Shoulder Guns Used in Whaling. a brass, steel-tipped dart. The iron was driven or thrown into the whale and when it penetrated 39

|

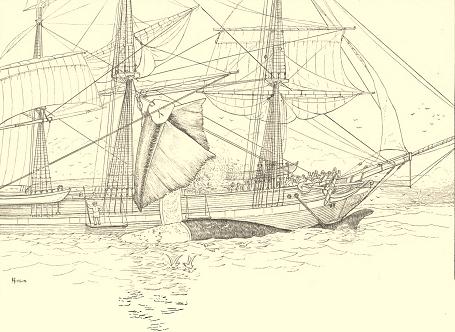

a certain distance a rod came into contact with the whale's skin and this sprung the trigger, discharged the "gun" and drove the heavy dart far into the interior of the whale. Whale guns and "darting guns" were also invented, some of which were worthless and others practical, but the real old-time Yankee whaleman found the common "iron" and the lance the most satisfactory weapons, and more whales were taken by these simple home-made appliances than by any other means. Nowadays the steam-whaling ships of Japan, Scandinavia and our Northwestern states use gun-harpoons weighing hundreds of pounds and fired from cannon, in order to capture the whales and then kill them by bombs or shells containing an explosive. It is mere slaughter with no element of danger or sport and such whaling is about as uninteresting and unromantic as killing steers in the stockyards of Chicago. But to return to the methods of the real Yankee whalemen. Once the whale spouted blood and was killed he was towed to the ship and made fast to the starboard or right-hand side by means of a chain around the small (the narrow portion of the body where it joins the tail or flukes), with the tail near the bow of the 40

|

Cutting-In Tackle.

41

|

ship and the head under the gangway – an opening in the ship's bulwarks between the foremast and mainmast and the process of cutting-in or securing the blubber commenced. Although,the method of cutting-in or cutting, as the whalers say, varied somewhat according to the species of whale, the principle was the same in every case and the method used in cutting in a sperm whale will serve as an example.

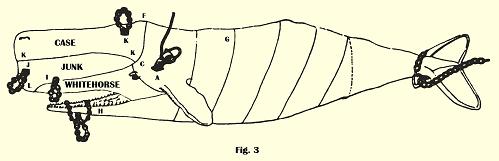

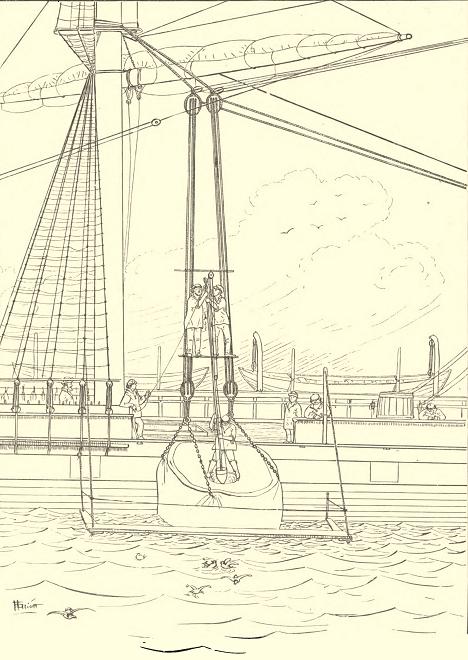

Cutting-In Sperm Whale (See text.) The main difference between cutting-in a sperm and a right whale lies in the details of handling the head, the entire head of the sperm being taken in, whereas in the case of the right whale the bone is removed and taken aboard. As soon as the whale is alongside under the cutting-stage (a frail platform of planks swung over the vessel's side), a hole is cut through the blubber between the eye and fin at the point A on the illustration and in this a huge, iron hook, known as the blubber-hook, is inserted by 42

|

Hoisting in the Case and Junk of a Sperm Whale.

Hoisting in the Lower Jaw of a Sperm Whale. |

one of the boat-steerers who is lowered in a bowline to the whale's carcass. Deep cuts are then made through the blubber at each side and across the end of the blanket-

Tools and Appliances Used in Cutting-In a Whale.

piece, as shown at C-D and C-F, and by means of a tackle attached to the blubber-hook the piece of blubber is torn from the whale's body and the creature is rolled over by the strain until it rests upon its side. 43

|

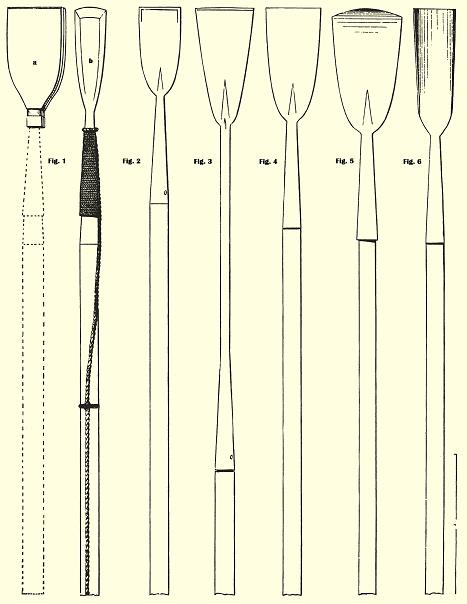

Spades.

44

|

Next a cut is made between the upper jaw and the portion of the head known as the junk, as shown by the line L-C, and if the whale is very large, another cut is made between the junk and case, as at B-E, and still another from E-F. An incision is also made across the root of the lower jaw, from the corner of the mouth to G; a chain is then attached to the lower jaw, as shown at H, and this is hooked or shackled to the second-cutting tackle and is raised while the tackle attached to A is slacked off, thus causing the whale's body to roll over on its back. Then by hauling on the jaw-tackle and cutting through the end of the tongue and the flesh, the lower jaw is separated from the head and is hoisted on deck. The first tackle, attached to the loose piece of blubber at A, is then hauled up by a windlass until the whale is turned completely over and cuts are made from L to C, from E to F and from B to E on the opposite side of the head. Close to the jaw at the point I a hole is cut through the junk; another is made at J and a third at K and to these "straps" and lines are made fast. The second cutting-tackle is then hooked to the strap at I, the fluke-chain is slacked off, and the tackle to A is lowered, and by hoisting away on the head 45

|

tackle the carcass is raised to an almost vertical position. From the cutting-stage men with spades (sharp-edged, square-ended knives at the ends of long poles) hack away at the spot between the jaw and junk C-L until the gash made is opened by the weight of the body. Then the root of the case from E-F is cut away, the junk and case or head are freed from the body and jaw and the great mass is fastened temporarily to the vessel's quarter. In some cases, however, the head is twisted from the body. By placing a stout, oakstave with one end resting against the ship's side and the other in a recess cut in the side of the head, and by hauling on the blubber-tackle the body is turned and the head wrenched off. When the head is clear the fluke-chain is hauled in until the whale lies alongside the ship: and the men commence stripping off the blubber. By cutting spirally around the body with the spades and by hauling on the blubber-hook tackle fastened to A, the blanket-piece is rolled or unwound from the body until the small is reached when the tail is cut off and the rear end of the body is hoisted on board. The head is then hauled up to the gangway, 46

|

Right Whaling. Cutting-In The Bone. |

Bailing the Case of a Sperm Whale. This method is used when the head is too large to hoist on deck. 47

|

Cutting-In a Right Whale or Bowhead.

48

|

one of the tackles is hooked on at J and the whole head hoisted on deck – provided the whale is a small one or of medium size – but if a very large one the junk is separated from the case at B-E as it hangs alongside and the junk alone is hoisted aboard. The case is then hoisted to the level of the deck, an opening is cut in it, and the spermaceti is baled out in case-buckets. If the whole head is lifted on deck the opening is made and the spermaceti is baled out after it is on board. As fast as the blubber, or blanket-piece, is taken from the whale it is lowered into the hatch and placed black skin down in the blubber-room where the men cut the mass of blubber into horse-pieces or chunks about fourteen inches square. These pieces are then taken on deck and are passed forward to the mincing horse where they are minced by means of two-handled, cleaver-like knives or by a mincing machine.

49

|

Meanwhile the fires in the try-works – brick fireplaces on deck near the foremast – are started with shavings and wood and the minced horse-pieces are placed in the great iron kettles to boil. As soon as the oil fills the kettles, it is ladled into the cooler and then into waiting casks, which are set aside to cool and are later stored below. The fires are fed by the scraps or cracklings from which the oil has been boiled out and, if at night, pieces of blubber are burned in the bug light (an open iron frame) to light the scene with its weird glare. When the blanket-piece has been tried out the junk or head blubber is cut up and tried separately, for this furnishes oil of a superior quality and is far more valuable than the body oil. The work of cutting-in and boiling is the hardest labor the whalers are called upon to perform and there is no lull in the activity and ceaseless toil while boiling is in progress. The boiling watch is of six hours' duration with half the crew on duty and while the officers (mates and boat-steerers) attend to the pots and fires and ladle out the oil some of the men are busy in the blubber-room, at the 50

|

Cutting a Right Whale from the "Stage".

Getting in the Head of a Right Whale. |

mincing horse or machine; others are sweating away storing the casks of oil, while one man is always at the wheel and another is constantly on lookout at the masthead. The hardest work of all was that of the crew

Cutting-In a Right Whale. Upper jaw and bone being hoisted on board. Note man with spade on cutting-stage; blanket-piece back of bone and try-works from which smoke is rising. who manned the windlass and tackles, for whalers had no labor-saving devices and the huge tackle-blocks were old-fashioned, worn and seldom greased and whaling skippers seemed tc delight in watching the men toil and apparently used every endeavor to make their work as hard and exhausting as possible. 51

|

Moreover, the process of cutting-in and boiling is inexpressibly dirty, nauseating work and how any human beings could stand it – much less choose it as a means of livelihood – is almost beyond comprehension. Slipping on the blubber-strewn deck, drenched with oil and grimed with soot, the work was bad enough, but the worst part came later, after the real cutting-in and boiling were over. The great lower jaws were left on deck until the gums rotted and allowed the teeth to be stripped from the bone, for the teeth were prized for carving and scrimshaw work by the crew and were divided among the men, and the stench of the decaying meat as it laid upon the deck beneath a tropical sun may better be imagined than described. Still worse were the casks of fat-lean. The fat-leans are those portions of the blubber stripped from the horse-pieces and which have fragments of flesh adhering to them and these were thrown. into open casks and left to rot, for the sake of the oil which drained from them during decomposition. After they had become thoroughly decayed the waste material was removed by the men who were compelled to fish out the putrid 52

|

meat with their hands and in order to do this they were obliged to lean inside the casks and to inhale the noisome fumes and terrible stench of the awful mass for hours at a time. But when at last the three or four days' unceasing labor was completed, the oil casks had been stored below, and the decks had been cleared up and washed down, the tired men had the time to themselves. All work ceased, save that absolutely necessary in handling the ship, and the members of the crew amused themselves by carving whales' teeth, making scrimshaw work or mending clothes until the cry of "There she blows" aroused all hands and everything was cast aside in preparation for the coming chase with its attendant perils, hardships and weary days of heart-breaking toil. 53

|

CHAPTER IVWHALING SHIPS AND THEIR CREWS

Staunch, seaworthy and "able" as they were, yet the old Yankee whaleships were neither graceful nor beautiful vessels. Speed, comfort and appearance were of no importance and the ships were heavy, bluff-bowed and "tubby." Of course there were exceptions, some of the whaling ships were the equals of any of the famous "clippers" for speed and graceful lines and were kept in the pink of condition, with standing rigging taut and well tarred, paint bright and fresh. 54

|

But the majority were slipshod, dingy, weather-beaten; bearing scars of countless battles with wind and sea, reeking with oil and grease and smelling to high Heaven. The old saying that a sailor can "smell a

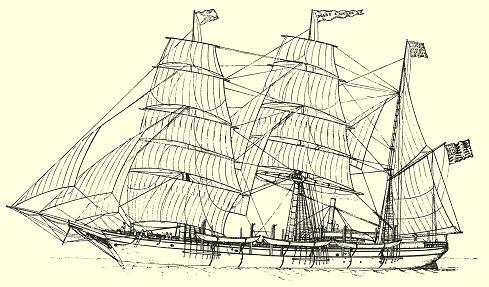

The Mary and Helen 0f New Bedford. A typical whaling bark equipped with auxiliary steam power. whaler twenty miles to windward" is scarcely an exaggeration. Betwixt catching, killing, cutting-in and boiling, the whalemen found little time to keep their vessels ship-shape. There were stove boats to be repaired, irons to be made, poles to be fitted, lines to be spliced, bent and coiled down, rowlocks to be 55

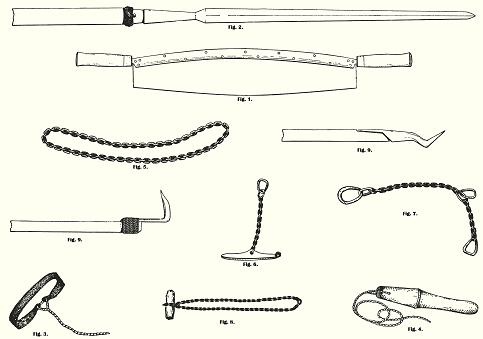

|

"thummed," straps to be made, knives, spades irons and lances to be sharpened and a thousand and one other duties to be attended to. What rest the crews had was well earned and in order that the men should be fresh and able to fulfill their duties they were allowed the time between one boiling and the next chase for their own amusement and recreation. As long as the ship held together and was able to weather the seas and gales, as long as it would carry its cargo of oil and bone, as long as the patched and dingy sails would serve to catch the winds and carry the whalers hither and thither, the whalemen were satisfied, and some of the old hulks, which were used for whaling, would appear fit only for the scrap-pile to a merchant sailor. I have seen whaling ships laid up in New Bedford and New London with grass and weeds growing from the crevices of their planking and yet a short time later these same ramshackle old craft were fitted out for long cruises and braved the storms and stress of the Arctic and Antarctic oceans and, strangest of all, returned safely to port full of oil. When after whales it mattered not if yard-long seaweeds bedecked the ships' bottoms or if 56

|

halyards, braces or falls were rotten and parted at a touch – the growths could be cleaned off at the end of the cruise and rigging could be patched and spliced. As long as whales could be caught, and until the hold could contain no more oil, the whale-

The Amelia of New Bedford. A typical whaling schooner. men kept to the broad oceans and when at last they sailed, fully laden, into the harbors of their home ports, they looked more like the Flying Dutchman or the ghosts of ancient wrecks than seaworthy ships manned by crews of flesh and blood. But if the whaleships sailed into port weed- 57

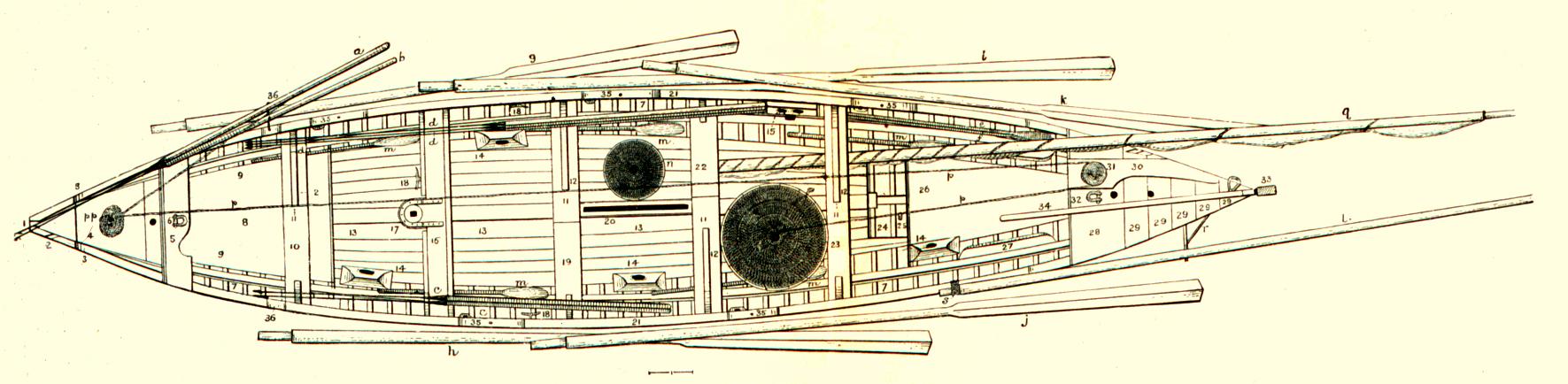

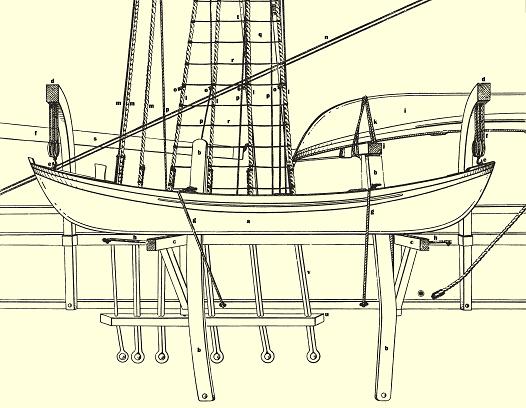

|

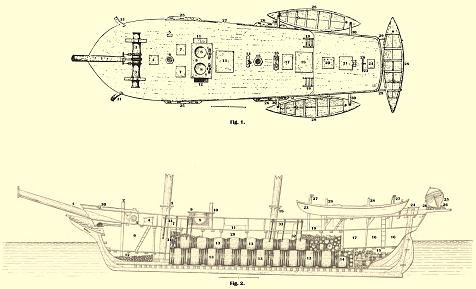

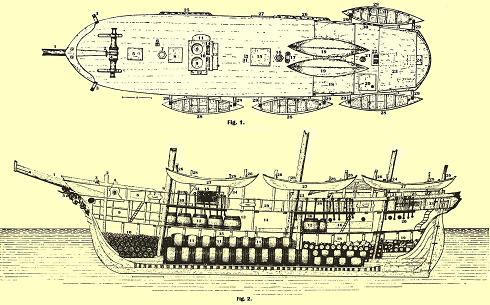

Deck and Sectional Plan of Schooner Amelia.

58

|

Deck and Sectional Plan of the Whaling Bark Alice Knowles.

59

|

grown, storm-beaten, patched and forlorn, as great change was wrought in them ere the capstan-pawls clanked and the men's chanteys echoed across the waters as they weighed anchors and manned sheets and braces outward bound. Rapidly the oil-filled casks were hoisted from the hold, spars and upper rigging were sent down, decks were cleared and soon the great, empty hulk rose high and light beside the dock. By means of gigantic blocks and tackle the hull was hove-down, exposing the ship's bottom and men standing on planks and rafts worked busily, cleaning off the accumulation of sea growths, repairing plates, caulking and overhauling. Top-sides were cleaned and painted; standing rigging was renewed, tarred-down and tightened; spars were scraped and sent aloft; new sails were bent on; old running rigging was replaced; and in a short time the ship was once more fresh, bright, spick-and-span and ready to refit for another cruise. Few people have any conception of the number of supplies and the variety of articles required in fitting out a whaling ship for a cruise. Aside from the necessary equipment which had to do directly with whaling, there were

The Return of the Fleet.

Whaleship "Hove Down" for Repairs. 60

|

supplies for the men, ship's stores, trade goods, tools, and a vast number of incidentals, the whole totalling some 650 different articles. Some idea of what was required may be obtained from the following list of "Articles for a Whaling Voyage," published by a New Bedford outfitter, Mr. N. H. Nye, in 1858 and which was used in fitting out the ship Janus:

61

|

62

|

63

|

64

|

65

|

66

|

Whaleships Fitting out for Their Cruises. |

From the above it will be seen that a whaleship was really a floating department store, carpenter shop, blacksmith shop, ship yard and several other things all rolled into one. But it was essential that the whalers should carry a very large number of stores which would never be needed on a merchant ship, for aside from the articles required in whaling it was necessary that a whaling vessel should be able to make any repairs needed on ship or boats for three years or more. As a rule they cruised in out-of-the-way spots where supplies, tools or other articles could not be purchased and the whalemen therefore set sail prepared for any emergency and equipped to 67

|

be absolutely independent of the rest of the world for years at a time. . When we stop to realize that nearly one hundred whaleships were often fitting out at New Bedford (and at other ports also) at one time, we can understand what the whaling industry meant to the New England ports. The tremendous quantities of goods purchased by the whalers is well shown by the following list of supplies furnished the New Bedford fleet of sixty-five vessels for the season of 1858:

68

|

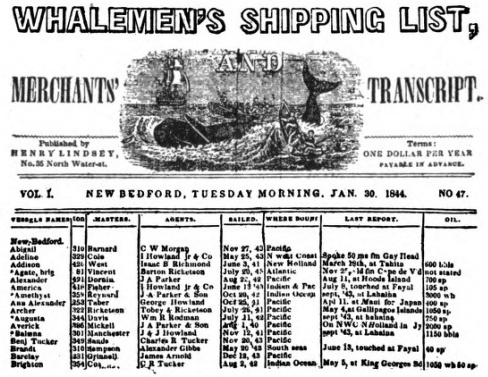

As these alone meant an outlay of nearly two million dollars it can be seen how much the tradesmen and artisans of such towns as New Bedford were benefited by the whalers and aside from the actual cash placed in circulation, a vast army of workmen, manufacturers and skilled laborers was built up, all of whom were dependent upon the whaleships for their livelihood. There were thousands of barrels and casks to be made, countless irons, lances and spades to be forged, hundreds of sails to be sewn, and innumerable boats to be built, as well as an endless number of other articles necessary to the whalemen and which could be made at the home port far better and more cheaply than elsewhere. Even newspapers and periodicals were published in which not a line or word was printed which did not relate to the whalers or was not of interest to the whalemen and their families and friends. Their pages contained adver- 69

|

tisernents of outfitters, ship-chandlers, dealers in nautical supplies, and similar tradesmen; there were quotations of exchange, the prices of oil and bone and pilotage fees; there were columns devoted to news from far-distant

Reproduction of First Page of the Whalemen's Shipping List. parts of the world reporting arrivals, departures, wrecks and catches of whaleships and, most important of all, were lists giving the names of all the whaling vessels of the Atlantic coast, their tonnage, captains and agents; when they sailed, where they were bound, where they 70

|

had been spoken and the amount of oil they had taken. In many a New England town "whale was king" in those days and the life, business, commerce – in fact the very existence of New Bedford and many other ports – depended entirely upon the whaling industry. Whole forests were leveled and great sawmills were established to furnish lumber, boards, staves and cordwood. Huge sail-lofts were kept constantly filled with busy workmen. Long rope-walks were built and nothing but cordage for whaleships made therein. Dozens of forges glowed from morn till night and hammer rang incessantly on anvil as irons, lances and blubber-hooks were forged by the toiling smiths. Boat-builders worked feverishly to keep the ships supplied with boats. Coopers toiled early and late making casks for oil. Clay banks were dug away and great kilns were erected solely to make bricks for the ships' try-works. Looms clicked and thousands of spindles whirred to make canvas, cotton and bunting for the whalemen. The crops of entire farms were raised to furnish the provisions for the whalers. Herds of cows were required to furnish the butter and cheese. 71

|

The docks were piled high, the warehouses packed full with whalers' stores, and an endless procession of trucks and drays toiled creaking over the cobbled, waterfront streets, laden with boxes, bales and barrels, all to go forth over untold leagues of sea in whaleships' holds. Moreover each and every workman, laborer or artisan did his best to produce results worthy of his name and that of New Bedford, or the town wherein he labored. Each took a personal pride in the success of the whalers and their catch; each knew that upon his individual skill, his honest labor, and the quality of his work depended the very lives of his fellows, and each put his whole heart and soul into what he did. The cooper knew that his casks must be tight and strong to hold the precious oil in safety during many months and in all sorts of weather. The blacksmith realized that upon the temper of his steel depended the capture or loss of the whales. The sail-maker knew that the canvas he stitched must withstand long weeks of drenching rain, months of broiling sun and gales of hurricane force. The rope-maker was aware that if his lines parted the stricken whale would escape, but of them all none worked with greater 72

|

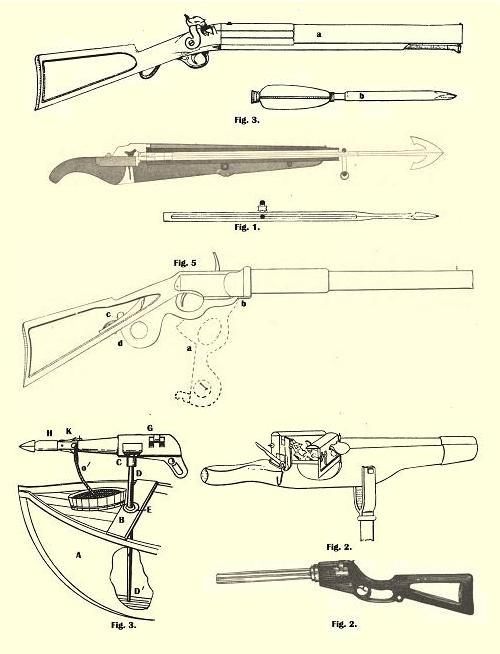

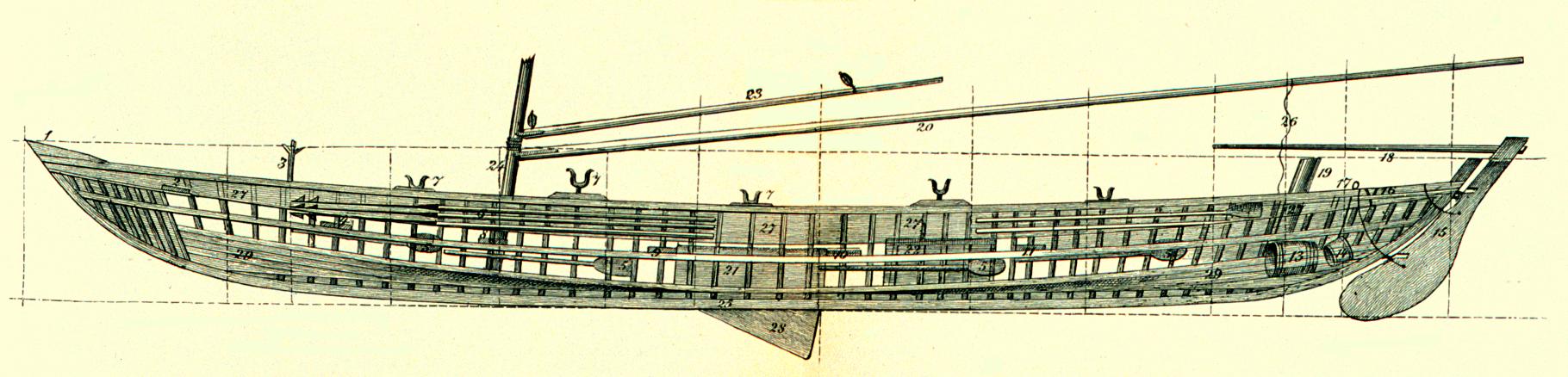

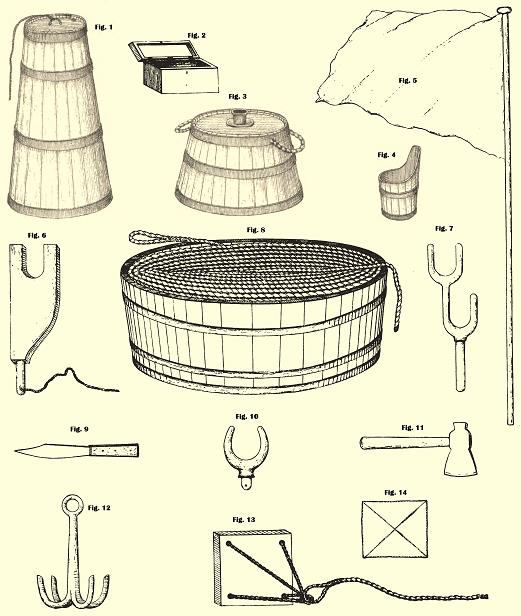

Whaleboat with Equipment as Used when Chasing Whales. |

care, none exhibited so much skill,-and none produced such perfect results as the makers of the whaleboats. To the whalemen the boats were of primary importance. In them the actual hunt took place, upon the boats' strength, lightness and ease of handling their lives hung and never did the boat-builders fail them. Through long years of whaling the boats had been developed until practical perfection was reached and never yet has boat been built which for speed, staunchness, seaworthiness and "handiness" excels the whaleboats of the Massachusetts whalemen. Thirty feet in length and six feet wide, with a depth of twenty-two inches amidship and thirty-seven inches at the bow and stern, the whale-boats seem mere cockleshells to one who is not familiar with them; but these tiny craft can ride the heaviest seas, can withstand the hardest gales, and can resist the most terrific strains with perfect safety. They are pulled by five great oars measuring fourteen, sixteen and eighteen feet in length, or are sailed by a simple sprit-sail, and are steered by a twenty-two-foot steering oar. The bow- and-tub-oars of sixteen feet are used on one side and pull against the fourteen-foot harpooniers 73

|

Section of Whaleboat. 1 – Bow-chock and roller. 2 – Clumsy-cleat. 3 – Crotch for harpoons. 4 – Harpooner's thwart. 5 – Paddles. 6 – Harpoons, with lances on opposite side. 7 – Rowlocks. 8 – Bow-thwart. 9 – Midship-thwart. 10 – Tub-thwart. 11 – After-thwart. 12 – Boat-spades and waifs. 13 – Lantern-keg. 14 – "Piggin" for bailing boat. 15 – Rudder. 16 – Steering-oar rowlock. 17 – Hoisting eyebolt. 18 – Tiller (used when sailing). 19 – Loggerhead. 20 – Boom for sailing (spritsails are often used). 21 – Center case (small tub for 75-fathom line on other side). 22 – Large tub for whale line. 23 – Gaff. 24 – Mast. 25 – Keel and floor timbers. 26 – Main sheet. 27 – Gunwale streak (about 9 inches wide in widest part). 28 – Centerboard (partly down). 29 – Ceiling. Timbers are spaced about 6 inches apart. 74

|

and after-oars and the midship oar on the other side, and propelled by these and the straining muscles of five men the boats fairly leap through the water. In their equipment the boats are as perfect as in their model and construction and each article has its own place and is always where it belongs. If an iron were mislaid, if a lance were out of reach, if a line kinked or if a hatchet were not at hand, six lives might pay the penalty for someone's carelessness. Near the bow, and resting in their cleats with keen tips sheathed are the irons and lances – two live irons, two or three spares, and two or three lances – all ready to the boat-steerer's or mate's hand. In wooden tubs are coiled the beautifully laid lines of finest hemp – three hundred fathoms in length. A hatchet to cut the line in case of need is in the bow-box; a water keg is lashed in its chocks; there are candles, a compass, lanterns, glasses and matches in lockers at the stern; a boat-hook, waif-flags, fluke-spades and canvas buckets are all in their appointed places, and paddles are at hand for approaching the whale silently when oars cannot be used. In the boat's stem is a deep slot to receive the 75

|

Deck View of Whaleboat and Equipment. 1 – Bow-chock. 2 – Lance-straightener. 3 – False-chocks. 4 – Box of boat. 5 – Clumsy-cleat, 6 – Strapiron. 7 – Timbers. 8 – Forward platform on which men stand when striking or killing, 9 – Risings. 10 – Harpooner's thwart. 11 – Knees. 12 – Dunnage for thwarts. 13 – Ceiling. 14 – Peak-cleats (used for resting oars). 15 – Peak-cleat for tub-oar. 16 – Bow-thwart. 17 – Mast-hinge. 18 – Sail-cleats. 19 – Mid-ship thwart. 20 – Centerboard. 21 – Gunwales. 22 – Tub-thwart. 23 – After-thwart. 24 – - Well for bailing. 25 – Plug (for emptying boat when hoisted out of water). 26 – After platform (steers-man stands on this). 27 – Standing-cleats (officer stands on these to obtain longer view). 28 – Cuddyboard. 29 – Cuddy-boards. 30 – Loggerhead-strip (or lion's tongue). 31 – Loggerhead. 32 – Boatshackle. 33 – Rudder. 34 – Tiller. 35 – Blocks with holes for rowlocks. 36 – Bow-cleats. A, First iron resting in bow-chocks with handle in boat-crotch. 76

|

line; at the stern is a stout post or loggerhead over which a turn of the line is taken when the whale is fast; the rowlocks are carefully thummed with greased marline to prevent the rattle, or squeal of oars, and in the forward thwart is the clumsy cleat or knee brace in which the whaleman rests his leg when throwing the iron at his quarry. Such are the boats used by the whal- ers and each ship carried several. Owing to the broad gangway in the starboard side of the ships only one boat is carried on the great wooden davits on the quarter of that side while the three others – if a four-boat ship – are slung to the davits on the port or larboard side. In addition, two extra boats are stored on overhead racks between the main and mizzen masts where they serve to cast a shade and to shelter the cabin. When at last the boats are in their places, the stores, provisions and equipment are aboard, and the ship is ready for sea, there is little room to spare aboard a whaler. In the forecastle the crew are quartered; in the forehold are spare rigging, hawsers, cutting-in gear and tackles, spare lumber, oars, anchors and similar things, and the main hold is filled with casks. To economize space these contain the supplies, pro- 77

|

Whaleboat Gear. 1 – Lantern keg containing matches, bread, tobacco, etc. 2 – Compass. 3 – Fresh-water keg. 4 – Piggin for bailing. 5 – Waif. 6 – Tub-oar crotch (this ships through cleat in gunwale to clear oar from line when fast to a whale). 7 – Double oarlock used as last. 8 – Large tub and line. 9 – Knife for cutting line when necessary. 10 – Rowlock. 11 – Hatchet. 12 – Grapnel. 13 – Drag. 14 – Canvas nipper to protect hands when hauling line. 78

|

visions, drygoods, trade goods, clothing and water for the cruise. Those of the lowest tier contain the water, others are filled with tins of bread and food, others with miscellaneous articles and those of the topmost tier hold the

Whaleboats in Position on a Whaling Vessel. things which will be used before the first whales are taken, so that when the grounds are reached the casks will be empty and ready for use. Every available niche and corner is full, the ship is as deeply laden as though a freighter with full cargo, and when at last the final bale and 79

|

bag is on board, and the full complement of men has been shipped, the whaleship is ready for her long cruise to the uttermost parts of the globe; perhaps to return fully laden in a few months, perhaps to cruise under tropic suns and through fields of ice for year after year, perchance never to return – sunk, no one knows when or where – one of that great fleet of "missing ships" whose fate is never learned. But what of the whalemen themselves? Without them the vast quantities of supplies would be useless, the carefully fashioned implements, weapons and equipment would be of no worth, the boats, perfect as they are, could not be used, and no whale could be captured, no oil obtained, and no cruise made. The personnel of an average whaling ship consisted of thirty-five or forty men whose ratings were as follows: captain or "skipper"; four mates or "officers"; four boat-steerers; a cooper; a steward; a cabin-boy; a cook; four ship-keepers, or "spare-men," and four boats' crews of four men each, or sixteen "seamen," besides an extra boy or two, a blacksmith and a carpenter, who were often carried. The duties of each man were definite and every member of the ship's company knew his 80

|

duty and performed it without question or hesitation. Each boat was in charge of a mate with its crew of four oarsmen and a boat-steerer and at times the captain took charge of a boat or lowered for a whale and in that case he took the fourth mate's boat and the latter officer acted as the captain's boat-steerer. The men in each boat were assigned to specific places and aside from pulling the boat they had other duties to perform. Thus the bow-oar was the place of honor and the man who pulled this oar was the mate's right-hand man and assisted the officer with the lances when killing. The midship was the longest and heaviest oar and the midship oarsman had little to do save pull on his huge sweep. The "tub-oarsman " threw water on the line to prevent it from burning as it ran rapidly out when the whale sounded, while the stroke-oarsman furnished the stroke to the other men and also aided the boat-steerer in keeping the line clear and in hauling in slack and coiling it down. The first or "harpoonier's oar," as it was called, was pulled by the boat-steerer when going on a whale until fairly near the creature. The boat-steerer then laid his oar aside and 81

|

took his place at the boat's bow and "struck" the whale with his iron, while the mate steered the craft with the huge steering-oar. Once fast the mate and boat-steerer changed places, the latter taking charge of the steering oar and becoming the boat-steerer in fact as well as name, while the mate took his position in the bow, to kill the whale. When the boats were away the ship, under shortened canvas, was left in charge of the captain (if he did not "lower"), the four spare- men or ship-keepers, the cook, steward, boys and cooper. Aboard the ship, when cruising, the crew or seamen had little to do, once they were on the grounds, save to swing the yards, trim sail or perform other work necessary in navigating the vessel; for every ounce of strength and every spark of vitality was conserved to be brought into instant use when a whale was sighted and the chase commenced. When on the grounds each boat's crew formed a watch, thus dividing the night into four watches of three hours each – if the vessel were a four-boat ship. Unlike the merchant sailors to whom eight-bell watches are almost sacred, the whalemen commenced them watches at six bells, 82

|

and in this respect they differed from all other seamen. Thus the first watch was from 7 until 11 P.M.; the middle watch was from 11 until 3, and the last watch was from 3 until 7 A.M. Moreover, half-hours were never struck on a whaling vessel's bell, only the even hours being sounded, and one, three, five or seven strokes never rang across the waters from a whaleship. At sunset the lighter sails were taken in, the topsails were reefed, and the ship was hove close into the wind with sails set, so she would remain nearly stationary and by occasionally "wearing ship" the vessel would be at practically the same spot at daybreak as on the preceding evening. This does not apply to the arctic whaling ships, however, for in high latitudes – where it was light throughout the night – whaling was carried on during the whole twenty-fours hours; in fact the first right whale taken in the Arctic was killed at midnight. In the daytime four men were kept constantly at the mastheads, two men forward and a mate and boat-steerer at the main, on the lookout for whales, and the ship would tack with long stretches to windward and would then sail down before the wind, thus covering nearly every square mile of the cruising ground. 83

|

But for the first few months of the cruise the men had far from an easy time and were compelled to labor from dawn until dark, as well as during the night watches; for there was general overhauling to be done, decks to be scoured, odds and ends to be stowed and, most important and hardest of all, the "green hands" to be broken in and trained. It may seem strange to think of "breaking in" a whaler's crew until we learn who and what the men were, for despite popular ideas and story-book tales the whalemen were never sailors. The old-time Yankee skippers were seamen – and wonderfully skillful and proficient seamen at that – as were the officers or mates, and the boat-steerers were practiced, skilled and efficient hands; but the crew, or so-called "seamen" – the men who furnished the sinew and muscle, the men who performed the hardest labor, the common soldiers of the army of whalemen – were "greenies." Derelicts of humanity from the gutters, raw-boned lads from the interior farms, ne'er-do-wells of respectable families, factory hands, clerks, vagabonds, gamblers, tramps, criminals striving to evade the law, loafers from park benches – they formed a motley crew culled 84

|

from far and near, and classed under the common appellation of "bums" by the officers and shippers. Some lured by the expectation of easily earned wealth; others thinking to find romance and adventure in the whaleman's calling; still others hunted from place to place and seeking the deck of a whaler and the wide seas as their only refuge, and still more drugged, filled with vile liquor and shanghied, they shipped as "seamen" on the vessels "bound to any seas" for any length of time, only to find themselves penniless, helpless, veritable slaves, whose master was the skipper with power beyond that of any king, their drivers the mates and their home the kennel-like fo'c'stle. Of true deep-water sailors there was no dearth in the ports from which the whalers sailed, but such men were not wanted on the whaling ships. Shippers and captains, owners and agents avoided the real seamen as they would the plague – they would not take them for love or money if it could be avoided and, as one captain remarked they wouldn't "ship a real sailor if he paid his passage." The reason for this strange state of affairs is obvious, if we consider the means and methods by 85

|

which the crews were obtained, the way they were treated, the work they were called upon to perform, and the actual earnings of the whalemen. 1 1 Whalemen never worked at regular wages, but were employed on "lays," or in other words, the ship's articles provided that each man should receive the proceeds of one barrel of oil out of a certain definite number. The division of the lays varied with different ships and in different years; the men and officers being satisfied with smaller lays in the early years of whaling, when oil was high, than in later years when the price fell. Just how the lays were apportioned and the amounts the members of the crew received as their shares from a cruise may be seen from the following examples: one of which shows the lays of a ship sailing in 1807; the other in 1860.

LAYS OF THE SHIP LION OF NANTUCKET, 1807

86

|

The crews were obtained through shipping offices with headquarters at New Bedford, or some other port, and with agents scattered here and there at the principal cities, especially in the Middle West and the interior of New England. By means of lurid, attractive advertisements and circulars these men drew the future whalemen to their net. They were promised a lay of the ship's catch – in other words, one barrel of oil out of a certain number – an advance of seventy-five dollars, an outfit of clothes, board

LAYS OF A NEW BEDFORD SHIP SAILING 1860

87

|

and lodging, until aboard ship; and glorious verbal pictures were painted of the easy life led, the enormous profits made and the strange lands visited on a whaling cruise. As fast as the men were gathered in they were sent to the port, where they were taken in charge by the resident agent and were placed in the cheapest and foulest of boarding-houses and were furnished with a so-called "outfit" of the shoddiest and most worthless sort. For each man secured, the shipper received ten dollars, in addition to all the expenses incidental to the transportation, board and outfit, and as this was not forthcoming until the men were aboard ship and at sea the shippers saw to it that the men were on hand when the anchor was hoisted. But what of the advance of seventy-five dollars promised, to each of the unfortunate men? From this imaginary amount were deducted all the expenses which the shipper defrayed, as well as the ten dollars head payment, and every article furnished, every item charged, was doubled, trebled or quadrupled by the rascally outfitters. An outfit costing five dollars at the most was charged to the men at twenty-five dollars, the tariff of the small boats for carrying 88

|

the men from the dock to the ship was doubled, the train fares were falsified, the boarding-house rates exaggerated, and when at last the account was presented and "signed off" by the poor, deluded, embryo whaleman he had not a cent of his promised advance coming to him. Of course none but green hands, men absolutely inexperienced in the ways of the sea and of whalers, would submit to this sort of treatment or would calmly accept the shoddy outfits and the outfitters' bills without a protest. No Jack Tar could be fooled, robbed and bamboozled in this way, and for this reason shippers and captains alike fought shy of the real seaman with his knowledge of "sharks " and their ways. This, however, was not the only reason why the whalers preferred the "bums" and farmers' boys to true sailors. A seaman might ship as a whaler with his eyes open or he might be shanghied and once at sea he might submit to the whaler's treatment and life, but at the first port he would desert and long before a foreign shore was reached he would make his presence and his dissatisfaction felt. Jack at best is a grumbler; he knows just how far his superiors can go; he knows what 89

|

he is entitled to, the duties he is supposed to perform; and among the riff-raff crew he would be sure to stir up discontent, trouble – mutiny, perhaps – and would become the leader, the dominant feature and the trouble-breeder of the crew. But by themselves the green hands were helpless and would stand almost anything without danger of causing trouble. Suspicious of one another, equally green and cowed by the officers, they were incapable of organized resistance. They had no one to whom they could look as a leader, they knew nothing of their rights, and everyone distrusted and disliked his fellows. This spirit the officers fostered and encouraged, for as long as the men hated one another there was little fear of a concerted uprising and any plots or plans made were sure to be reported by some member of the company. In one respect, however, the men of the crew were in perfect accord – they all hated and detested the mates, although fearing and obeying them. Even the danger of desertion was so minimized as to be unworthy of a thought. The men were penniless, they were not sailors, and in most cases had no trade or occupation with which to keep soul and body together if they left 90

|

the ship. In a foreign port they would be worse off than on the sea, for they were ignorant of the languages, they could not ship on another vessel, and they did not even know that they could appeal to a consul to be sent home as distressed seamen and even if they did so, they were in fear of the results when they reached the States. True sailors, on the other hand, would have no such difficulties, and the few that were now and then shipped – usually by accident – left the vessels at the first port at which the whalers called. Oftener than not the officers were glad to be well rid of them, and many a desertion was suggested by the captain or his mates who handed a few bills to an undesirable member of the crew and hinted that he would not be missed until the vessel was on the high seas. But the whalemen who ship on the few whaling vessels that sail from New Bedford to-day are mainly men of a different sort – Portuguese from the Azores or the Cape Verde Islands – many of them nearly full-blooded negroes and black as ebony, but hard working, industrious and good whalers. These men "know the ropes," they are well able to look out for themselves, and are far too 91

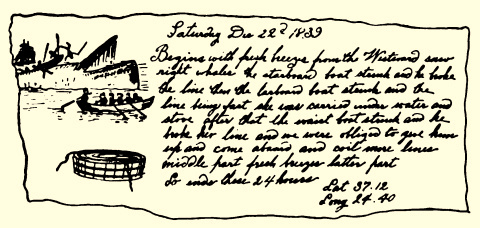

|