|

Francis A. Olmsted Notes |

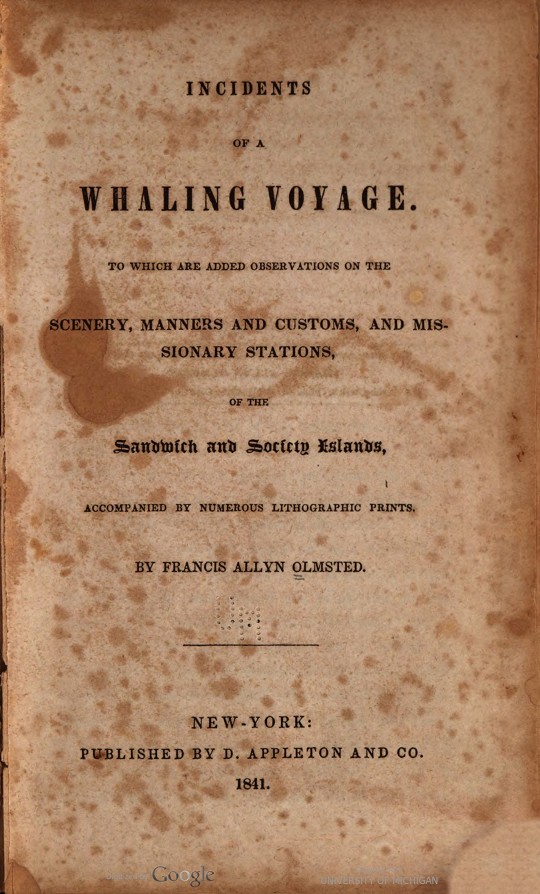

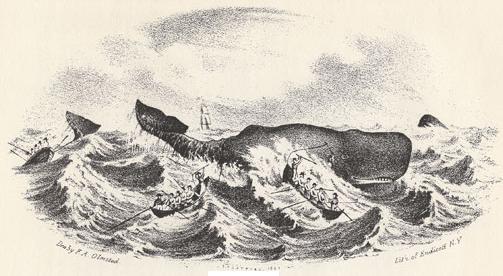

Perils Of Whaling. |

|

Entered, according to Act of Congress, in the year 1841, by

FRANCIS ALLYN OLMSTED, In the Clerk's Office of the District Court of Connecticut. |

PREFACEDuring the latter part of my collegiate course, my health became very much impaired by a chronic debility of the nervous system, and soon after graduating, the cold air of Autumn admonished me to seek a milder climate for spending the winter. While deliberating upon what would be most desirable in accomplishing the purpose I had in view, a favorable opportunity was offered me to go out as passenger in the whale-ship "North America," which was fitting out at New-London for a voyage to the Pacific. From an erroneous prejudice against whalers, it was with great reluctance that I determined upon embarking on this voyage, and many of my friends made sage predictions of the wretched life to which I was consigning myself. A strong inclination for the sea, however, which had made |

ships and the ocean my admiration from boyhood, and a love of the adventurous, inclined me to a voyage in preference to any other plan for the recovery of my health; and its successful results have left me no reason to repent of my choice. With the exception of the interesting work by Beale, entitled "The Sperm Whale Fishery," I am not aware that any representations of whaling life have been exhibited proportionate to its adventurous character and importance. Entertaining sketches of the capture of the whale, have been written at different times; but they are generally the productions of those who were not spectators of the scenes they attempt to delineate, and must, of course, be wanting in accuracy. I have endeavored to represent sea-life as it is; and should the reader, impatient to enter in medias res, think me tedious in getting under way, I have only to plead that the facts were so; and similar delays and vexations are believed to constitute a very ordinary part of sea-life. It has also been my constant endeavor throughout the narrative, to make a candid representation of occurrences, although I do not aspire to infallibility. Some parts of my narrative may appear to be wanting in exciting incident. My object has indeed been, to represent life in a somewhat novel aspect, but not by a sacrifice of truth or by an exaggerated picture. The common incidents of life, in their or- |

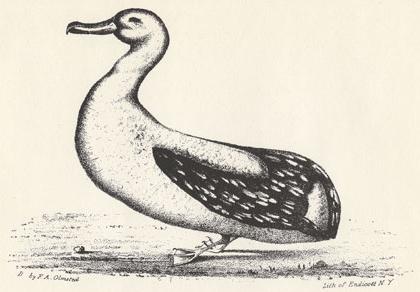

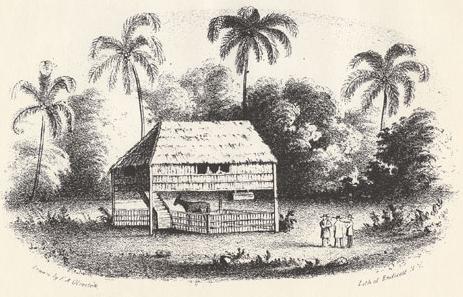

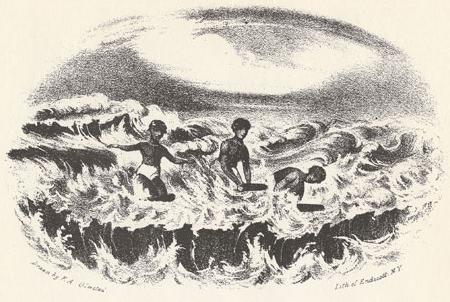

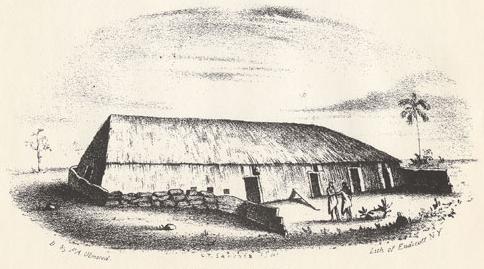

dinary course, rarely exhibit much of the marvellous, and it is from the reality of their occurrence, in a great measure, that they excite permanent pleasure. A Marryatt, by weaving together the events of several voyages, and coloring the tissue with all the vividness of a lively imagination, gives to his sea sketches a brilliancy which a strict adherence to the common course of events would have denied him. The pictorial illustrations are selections from fifty or sixty sketches representing objects of natural history, and scenes that interested me, taken originally in the sketch book I always carried with me, and finished off afterwards, as soon as possible. The great expense of these illustrations, forbids the introduction of a larger number into the work; for the size of a work gives it a determinate price, from which even the most expensive illustrations will not admit of very great deviation, although embellishments of this kind are often as essential in forming a correct idea of a scene, as the printed page itself. Frequently indeed, they are of greater importance; for a single glance at a correct picture gives a far more vivid idea of a scene, than the most elaborate description. Some of the statistics of the Whale Fishery, were gathered after my return, and have reference to a date subsequent to that of the journal where they are introduced. This arrangement, although censu- |

rable as an anachronism, is not deemed inconsistent with the nature of the work, and is thought preferable to multiplied notes. In conclusion, I have endeavored to represent the sailor in a favorable light, and to excite the kindness and sympathy of the benevolent in his behalf. If my efforts have been successful, and shall contribute to secure to the whaling business, that share of respectability which has been withheld from it through ignorance and prejudice, I shall esteem myself happy. New-Haven, August, 1841. One so young, and so little known to the public as the author, may, it is hoped, be permitted to annex the following certificate from Messrs. Havens & Smith, Hon. Thomas W. Williams, M.C., and Francis Allyn, Esq., Mayor of the city of New-London, to whom he had submitted his manuscript. Captain Smith is an experienced whaler, and has often visited the regions described in this work. New-London, May 5th, 1841. Mr. F. A. Olmsted having submitted to our examination parts of his manuscript journal of a voyage in our ship "North America," in 1839 and '40, we take pleasure in testifying to the correctness of his descriptions of the Sperm Whale Fishery and the accompanying plates, and we think he has the materials for an interesting work. HAVENS & SMITH. We concur in the above opinion. TH. W. WILLIAMS. |

CONTENTS.

| ||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

ILLUSTRATIONS.

|

INCIDENTS OF A WHALING VOYAGE.CHAPTER I.VOYAGE TO THE AZORES.

Friday, Oct. 11, 1839. – Early this morning, the rattling of blocks and rigging, and the animating cries of the seamen, announced that the North America was getting under way; and soon the barque with her swelling sails distended by a gentle breeze, swung from her moorings. The wind was fair, and as we glided out of the beautiful harbor of New-London, the clear air of the morning, the favoring breeze, and the bright sun mirrored in a thousand tiny waves, soon dispelled the gloom of parting from those I loved, and even inspired me with renovated spirits. The band of the Revenue Cutter was going through its morning exercises, and I listened to the national airs it was performing, until growing fainter and fainter, they were lost in the distance. A new feeling of patriotism was awakened within me; and these simple strains, that on ordinary occasions, would scarecly have been heeded, were now associated with many endearing recollections, and invested with a melody and sentiment I had never before discerned in |

them. Month after month will perhaps have rolled over me, ere I shall again hear the inspiring strains of "Hail Columbia, happy land," in my own favored country to which I am now bidding adieu – it may be forever. But from these painful suggestions that now and then struggled to obtain possession of my mind, I turned with interest to the scenes as they opened before me in my new habitation, the first aspect of which was not the most favorable. The North America is a Temperance ship; that is, no ardent spirits are served out to the men on any occassion. This, however, does not preclude them from becoming intoxicated whenever an opportunity presents itself, which two or three of them, judging from appearances, would not be very reluctant to embrace. The prospect of a voyage of three or four years in length is an incentive to greater excess, while intoxicating liquors can be purchased to drown the unpleasant anticipations incident to so long a separation from country and kindred. Inebriety is by no means as prevalent among sea-faring people as was formerly the case, since the abandoment of the idea that intoxicating drinks were indispensable to the sailor. It has been within a few years only that the plan of sailing ships upon temperance principles, has come into extensive use; before this, if a master of a ship, in visiting another, declined a glass of spirits, his refusal was regarded as an insult. Soon after the commencement of the temperence reform, Major Williams, of New-London, determined to lend the weight of his extensive influence in promoting temperance aboard the whale-ships sailing out of this port, in which he was interested. His exertions, although meeting with great opposition at first, were successful – other influential men |

followed his example – and now, out of the thirty or forty whaling vessels belonging to the port of New-London, almost all are navigated upon temperance principles. To the credit of the American Whale Fishery, it ought to be added, that the proportion of vessels of this character, is much greater in this service than in any other department of our marine. This afternoon, as I was standing at the starboard gangway, watching the progress of the ship through the water, a sailor passed by me, and letting himself down the side of the ship by the chains, very deliberately threw himself overboard, and commenced swimming towards land, then distant three or four miles. "Man overboard! – man overboard!" resounded from every part of the ship – a boat was lowered, manned, and put off to rescue him from a certain death. He swam very well, however, although encumbered with heavy woolen clothes, but was soon overtaken, hauled into the boat, and held down as he endeavored to plunge into the sea again. After a change of clothes, he was put into his berth, with some one to watch him, lest he should make another attempt to leave the ship. This man is a boat-steerer, (a grade of petty officers aboard a whaler, about whom I shall speak more particularly by-and-by) and a first-rate seaman, who had been to sea all his life-time, and had seen all kinds of service. For a week or two before the sailing of the North America, he was constantly intoxicated, and this insane attempt to leave the ship, was owing to the maddening and stupefying effects of constant inebriety.* * He afterwards became a very good friend of mine, and gave me a variety of information about ships, and "spun me many a yarn" of his adventures at sea. |

The wind, which during the day, hardly moved the ship through the water, as evening came on, veered ahead. A head tide also, opposed our progress, and as the sky towards the south-east looked lowering, with some indications of a gale, it was thought advisable to return. The ship's head was soon pointing towards New-London, distant about twelve miles from the shore, where we lay during the night. Early on Saturday morning, as the wind continued to increase from the south-east, we hauled in opposite the light-house. Sunday, Oct. 13. Soon after the ship was moored, yesterday, I went ashore with Captain Richards and the pilot, where we remained until this morning, when at an early hour we were summoned on board ship, as the weather seemed favorable for going to sea. But our expectations are disappointed, and here we lie without breeze enough to carry us out, while a damp atmosphere and cloudy sky, render our situation extremely dismal. It is the Sabbath too, and while the solemn tones of the distant church-bell should awaken emotions befitting the day, our own unpleasant situation engrosses all our attention; and instead of occupying our minds with the solemn duties of the Sabbath, we are watching the clouds for indications of fair weather. Monday, Oct. 14. "Boat-ahoy," hailed the officer of the deck, as a boat was seen coming down to us, rowed by two boys, carrying a large bag in the bow of their tiny craft, intended for the ship. We were endeavoring to divine the contents of it, which were supposed to be of a highly valuable character, from the important air exhibited by the boys. The bag was hoisted upon deck and opened, when out jumped an old cat and her numerous progeny, that ran squalling around the deck to our sur- |

prise and diversion. Cats are consequential personages on board, as they protect us from the depredations of huge cock-roaches that swarm in every direction. I found one of these erratic black-legs the other day, up in the main-top, wandering about very much at his leisure. Captain R., a few days ago, in speaking of the good qualities of the North America, said that "she was built entirely of live oak," which subsequent observations have fully verified! Last evening, the clouds for a short time dispersed, and the stars and the moon beaming forth, seemed to promise a favorable change in the weather. Not long after, however, the sky was again overcast, and before morning, an easterly storm came pattering down upon deck, with the gloomy prospect of another dismal day. If I had not started with a good resolution to be disconcerted by nothing that might happen, I should by this time have been tempted to give up an entereprise so inauspiciously begun. "So much for sailing on Friday," an old salt would say. There has been a singular superstition prevalent among seamen about sailing on Friday; and in former times, to sail on this day, would have been regarded as a violation of the mysterious character of the day, which would be visited with disaster upon the offender. Even now it is not entirely abandoned; and if a voyage, commenced on Friday, happens to be unfortunate, all the ill-luck of the voyage is ascribed to having sailed on this day. An intelligent ship-master told me, that although he had no faith in this superstition, yet so firmly were sailors formerly impressed with superstitious notions, respecting this day, that until within a few years, he should never have ventured to sail on Friday, for the men would be appalled by dangers which they would think lightly of on common occasions, and their efforts |

would be paralyzed by their imaginary fears of being under a mysterious and malignant influence. I have been told, that several years ago, a ship was built and sent to sea, to test this superstition, and convince the craft of its folly. The keel of the ship was laid on Friday; on Friday her masts were set; she was completed on Friday, and launched on this day. Her name was "Friday," and she was sent to sea on Friday; but unfortunately for the success of the experiment, was never heard of more. As knowledge advances, all opinions not consonant with reason must be abandoned, and this superstition is fast losing its hold on the minds of sea-faring men, especially since the establishment of the packet lines, and the frequent necessity of sailing on Friday. It had its origin, I am told, in the ancient custom of executing criminals upon this day, which imparted to it an unlucky character. I have also heard it ascribed to a connection with some of the observances of the Roman Catholic Church, which entertains some peculiar notions with regard to this day. Tuesday, Oct. 15. Rain – rain – rain – with a raw wind from the north-east– cold and cheerless on deck – damp and dismal in the cabin. For our encouragement, the barometer, which for the last three days has been continually falling, is now rising, indicative of fair weather. This morning, hearing an unusual noise upon deck, I ran up the companion-way, and, at the distance of thirty or forty yards from the ship, saw one of the men making desperate efforts to reach the shore by swimming. One of the boats had just been lowered – pursuit was instantly made, and the man with but little resistance, was secured and brought on board, crest-fallen |

enough in his dripping clothes, with his shoes tied around his neck. "Come here," said the commanding officer, (the second mate) in an authoritative tone. "Well, you were going to leave us in the lurch, were you?" "Why sir, Mr. L–– (the first mate, who was on shore) told me I might go ashore with him, and he went off without me." "And so you thought you'd work to windward of us in this way, eh?" "Why sir, I thought he didn't do what was right." "You thought? Well, I'll tell you what I think, and I'll inform you in the most delicate manner, that if you show any more of such fandangos here, you'll be clapped down into the lower hold, sir, with some irons around your wrists, that don't look quite so pretty as ladies' bracelets neither – bear that in mind, and be off, sir." The crew, though very quiet in general, are beginning to show signs of impatience, and if there are no indications of fair weather at sunset, an attempt will undoubtedly be made to desert during the night. With the few exceptions I mentioned before, they are very temperate, and I have heard but little bad language or profanity on board, both of which are prohibited by the Captain. Captain R. left us last Sunday evening, and has not yet returned. I should have accompanied him up to town, were it not that I had already bidden my friends "good-bye" three times, and did not like to impair the virtue of the "Farewell" by repetition. Wednesday, Oct. 16. Yesterday afternoon the clouds began to break away, and the sun shone forth to gladden us after a long absence of his cheering beams. The moon too, favored us last evening with her kindly radiance, and long I paced the deck, musing on the reality of the enterprise in which I had embarked. When |

we are preparing for a long voyage, we talk of separation from home, kindred, and country with a kind of vagueness as if it would never be realized; but when we have actually embarked, and there is no return, then the reality comes vividly to mind, and impresses us with the magnitude of the enterprise; while the uncertainties of the future forbid our anticipating its termination. The future to me is more than ordinarily uncertain. To picture to myself my various wanderings over the mighty ocean, in accommodating myself to the erratic life I have now chosen, and after leaving my present shipmates to trace out my circuitous course back to my native land, is beyond the reach of mortal ken and were a vain attempt. And there are solemn musings too. Ere I return, the irrevocable hand of death may invade the home of my youth and the circle of kindred friends, and consign one or more to the grave! Ah! these are the saddest thoughts, that press like an incubus opon the spirits of the voyager as he leaves his native shores. Early this morning, the Captain came on board, and soon we "hove short" – the sails were loosed – the top-sails sheeted home – the anchor weighed and catted, and we were standing out of our anchorage. It was a lovely morning. The sun just emerging behind the long line of hills that bound the eastern side of New London harbor, was fringed with the light fog that floated down the river, tinged with his golden rays. With the light wind that fanned our sails, we glided slowly along over the smooth waters of the sound, and by noon, having passed through "the Race,"* were directing our course towards Montauk Point. * That part of Long Island Sound between Fisher's Island and Gull Island, is called "the race," on account of the velocity of the tides between these islands. |

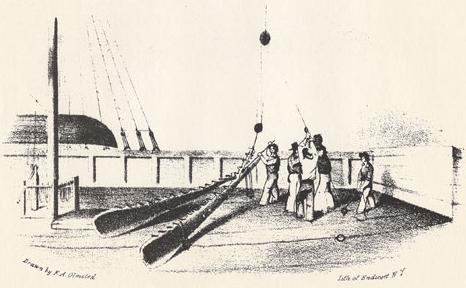

Thursday, Oct. 17. The wind has been light and baffling since yesterday. This noon there was a perfect calm, and upon the eighth day from the date of our first setting sail from New London, we find ourselves at anchor off Montauk point, to prevent being drifted ashore, instead of tossing about upon the Atlantic one third of the way across. All hands have been engaged in various duties about the ship, such as overhauling the spare canvass, and stowing away articles more compactly. The boats too, have been put in complete order, to be in readiness for the first opportunity that presents itself for using them, and although it may be a deviation from the plan I have adopted, I cannot do better, perhaps, than to describe the whaleboat and its various appurtenances. The whaleboat is a narrow, light built boat of about twenty-five feet in length, sharp at both ends, with its sides gracefully curved and running up to a point fore and aft, and from its construction, is expressly adapted to great velocity of motion and safety among the swelling billows of the ocean. Unlike most ship's boats, it is clinker built, as this peculiar mode of construction is called, i.e. the thin boards that cover the ribs overlap one another, thus giving strength to the boat and enabling it to be made much lighter. Each boat is fitted with six oars of various lengths. The steering oar, usually from twenty to twenty two feet long, is confined to the boat by a strap passing around it and attached to the sternpost. This gives the helmsman great power over the movement of the boat far superior to the steering with a rudder. The thole pins, between which the oars are plied, are covered with matting, so as to prevent any noise in the |

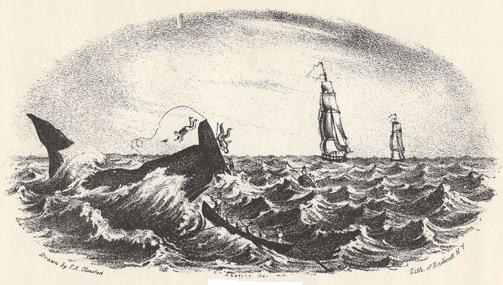

motion of the oars. Of the offensive weapons, the harpoon is the most important.

The harpoon is an iron instrument, about four feet in length, terminated at one end, in a sharp barbed head, and at the other, in a socket for receiving the "iron pole," a heavy wooden handle of about equal length, which gives to the instrument great momentum. A strap with a turn around the socket of the iron secures it upon the pole. To the strap is attached the line, a strong rope about two hundred fathoms long, which is carefully coiled up in a tub placed in the afterpart of the boat; and going around the "loggerhead," a strong post projecting above the stern, passes through a "chock" or grove in the bow of the boat, and is "bent on" to the harpoon. Each boat usually carries four or five harpoons, two of which are always ready for immediate use when the boat is in pursuit of whales. Their barbed heads lie across the bow of the boat, with their shafts resting upon two "crotches," or spurs, standing out from a stick rising from the side of the boat. This position gives steadiness to the weapon, and it is close at hand whenever opportunity offers for using it. |

The lance is two or three feet longer than the harpoon. Its head is of an oval shape, pointed with steel, and its shaft is long and slender, with the "warp," a small line about eight fathoms long, attached to the extremity of it. The spade is a short instrument, with a thin, wide blade set upon a light shaft of five or six feet in length. These instruments are ground to a very keen edge, and kept constantly bright. Their sharp heads are enclosed in sheaths, to defend them from injury, as also to prevent their doing any mischief. A hatchet, a couple of knives, a water-keg, a lantern, and a boat compass, together with one or more buckets, complete the equipment of a boat. Six men constitute a boat's complement. Of these, the captain or one of his mates is one, who directs the attack upon the whale. There is also a subordinate officer called boat-steerer, who performs the duties of a cockswain, taking care of the boat with its appurtenances. To each man is assigned an oar and a station in the boat, to avoid any confusion when starting in pursuit of a whale. In attacking the whale, the captain or one of his officers takes the steering oar, and directs the boat in the onset. The boatsteerer pulls the short oar in the bow of the boat, and at a signal or command from the officer, draws in his oar, and taking his stand firmly in the bow, when the word is given, darts the harpoon with all his strength into the whale. Sometimes he is so successful as to fix both irons, which generally ensures the capture of the struggling monster. He now exchanges places with the officer, and takes the steering oar, while the latter comes forward to thrust the lance into the vitals of the whale whenever he comes up to blow, a feat re- |

quiring no ordinary dexterity. The moment the whale begins to slacken the line to which he is "fast," it is hauled in, and coiled up carefully in the tub, while the boat is drawn towards the whale, as he comes on top of water, when he receives several thrusts of the lance in succession, which often enters to the depth of several feet. When the animal is very violent in his movements, a few strokes of the spade across the sinews of his flukes, disable these his most powerful weapon of defence and motion. The line is confined to the grove in the bow of the boat by a wooden peg, which breaks in case the line becomes entangled, thus averting the extreme danger of being instantly carried down. Thus much for the description of the whale-boat at present, which in grace and velocity of motion, is not excelled by any ship's boat. On board of all vessels, the men are separated into two divisions, called the larboard and starboard watches. The first and third mates command the larboard watch. This morning, the crew were all summoned upon the quarter deck, and the first and second mate selected alternately, the members of their respective watches. The Captain and each of the officers, in a similar manner, in the order of rank, then made choice of the required number for the boat he commanded. Friday, Oct. 18. Last evening the ship was again under way, and at sunrise this morning, land was no where visible. There was scarcely breeze enough to steady the ship, while as far as the eye could reach, not an object presented itself to break the monotony of the ocean, with its ceaseless undulations, or to impair the emotions of sublimity with which vastness of extent impressed me, as I scanned with eager eye, the uninter- |

rupted curve of the horizon. The open ocean is rarely calm, such as we see in the waters of our lakes and rivers. Even in its stillest moments, when not a breath of air agitates it, its surface is perpetually heaving as if with some internal commotion. For the fathomless waters of the ocean acquire such a momentum when the storm comes over their depths, that even when the winds are hushed, they do not soon subside. Tuesday, Nov. 5. In resuming the thread of my narrative, which has been interrupted for more than two weeks, I cannot do better perhaps than to commence from my last date, and endeavor to give a slight sketch of what has befallen me in the meantime. On Saturday, Oct. 19, towards evening, the rain began to fall in frequent showers from the South. About 11 o'clock that night, I was roused from my slumbers by the rolling of boxes in the cabin, and the crash of the steward's crockery in the pantry, the howling of the wind and the loud tone of command from the officer on deck. "Tumble aft – tumble aft here every one of you. Let go your top-gallant halliards fore and aft – clew up – mind your helm – keep her off before it – main-tack and sheet let go – clew him up, clew him up – jump, for your lives, men – top-sail halliards let go – one of you give 'em a call there in the forecastle and steerage." "All hands a-hoy," just heard above the roar of the winds, summoned the larboard watch on deck, as we sprang up the companion-way to ascertain the cause of the sudden alarm. We had been moving along under easy sail, when upon nearing the gulf stream, a heavy squall struck us from the west. The top-gallant sails and top-sails had been settled down, while the main course was flapping about with a noise like thunder. In a short time, however, all the sails were snugly |

furled, with the exception of a close-reefed main-top-sail and fore-sail, under which we drove before the gale that pursued us across the gulf stream. The next day (Sunday) a sea struck our larboard quarter boat, and dashed her to pieces, – a bad omen for the commencement of the voyage. We have since had another boat stove by the violence of the sea, which dashes in very frequently across the waist of the ship. I had brought a thermometer with me for the particular purpose of ascertaining the temperature of the water in the gulf stream; but the violence of the sea put an end to all philosoophical speculations. I was informed, however, by those that were drenched by the spray, that the water was very warm.– The air, too, was mild, unlike the storms we have at home in the month of October, in this respect. Indeed, the temperature of the ocean air off soundings, is always much higher than that of the land in the same latitudes, out of the tropics in the cool season of the year. For the three weeks, during which we have been at sea, we have had no weather cold enough for an overcoat, except at night, although at home, I presume, anthracite fires are glowing to repel the first approaches of winter. In a day or two we had crossed the gulf stream, and were promising ourselves a delightful run to the Azores, when the wind came around ahead from the eastward, where it continued for eleven days without alteration. At one time we ran down as far as the Bermudas, and were admonished to alter our course by frequent squalls that assailed us. During the stormy weather in the gulf stream, I confined myself to my berth, as the most comfortable place * Its known temperature in this latitude is about 72 deg. |

I could find, and with bundles on each side of me, endeavored to keep myself from rolling about. The motion of the vessel, and the intolerable smell of bilge watere which came steaming up from the hold through the crevices in my state room, brought on a disease, that for more than two weeks, completely disabled me. It was not sea-sickness under which I labored, but an extreme debility accompanied with fever. There can be no mistaking the former, and I considered myself well versed in it from an intimate acquaintance during several coasting voyages. A determination to rise superior to my physical weakness, was the only thing that enabled me to counteract the extreme depression that assailed me; and I have never been more convinced of the truth of a saying which has almost become a proverb – "that a resolute spirit has greater efficacy in combatting our bodily ills, than medical prescriptions." No disrespect to the profession, however. When we are sick on shore, we obtain good medical advice, kind attention, quiet rest, and a sell ventilated room. The invalid at sea, can command but very few of these alleviations to his sufferings. The attentions he receives, have none of that soothing influence, which woman's tender sympathy alone can impart. Undisturbed repose is out of the question, where every thing is in motion and the bulkheads are dismally creaking. The air of the cabin of a ship is always close and uncomfortable in bad weather. Let a man be sick any where else but on shipboard. For the last three or four days, the wind has hauled around to the west and north-west, with frequent squalls. Hardly a day passes, but the wind comes whistling down upon us, and lashing us awhile in its fury, leaves us to be soon succeeded by another, when the same scenes of |

"letting go the halliards – clewing up and clewing down – " are enacted over and over again. During the intervals, the ship rolls heavily in the sea, and the deck is washed by the sea breaking in across her waist. Buckets, pieces of wood, and other loose articles run around the deck in wild disorder, to the serious annoyance and hazard of one's nether limbs. Shower baths provided gratis for those who are not on the look-out for themselves. We have seen no whales as yet, and even if we had, the sea has been too high for a boat to venture out in pursuit. During the frequent squalls of the few days past, I have been delighted with the beautiful rainbows that formed at all hours of the day – now spanning the heavens in a regular arch, then rising above the sea like two pillars of resplendent colors, and again but just tinging the clouds with their brilliant hues. We are now about eighteen hundred miles from the United States, and expect to reach the Western Islands in six or eight days. |

CHAPTER II.FAYAL.

Tuesday, Nov. 12. This morning at seven bells (7 1/2 o'clock) "Land-ho!" was sounded from mast-head, and soon the high hills of Fayal, one of the Western Islands, were dimly seen through the mist that shrouded their summits. The Azores, or Western Islands, as this group is usually called, lie within the parallels of north latitude 39° 44', and 36° 59', and the meridians 31° 7' and 25° 10' west. They are nine in number, spreading over a considerable extent of ocean, and distant from the United States about two thousand seven hundred miles. Their names are Corvo, Flores, Fayal, Pico, St. Jorge, Graciosa, Terceira, St. Miguel, and Santa Maria. To me the sight of land was very acceptable, after the report I had heard of the tropical fruits growing upon these islands; and it was with great pleasure that I saw the beautifully verdant hills of Fayal rising rapidly before us, as we neared them before a fair and fresh breeze from the westward. Fayal presents a somewhat picturesque appearance; its surface is very undulating, and high hills crowned |

with the richest verdure, complete its outline. We coasted along the south side of the island, where the shore is very bold, rising abruptly from the ocean, while the surf breaks incessantly in foam and spray upon the rocks that line the coast. Each hill-side was covered with innumerable patches of the richest green, which, I believe, were fields of grain. On this part of the island, there are but few trees of any magnitude. Around the sparsely scattered houses, that we saw through the spy-glass, we observed, however, small clusters of shrubbery. To the eastward of Fayal, separated by a narrow channel about five miles wide, is the island Pico, with its mountainous summit, called the Peak of Pico, towering into the region of the clouds. Its height, I am told, is 7,016 feet or I 1/3 miles above the level of the sea; and for the greater part of the time, it is entirely obscured by the mists that rest upon its summit. As we approached Fayal, just abreast of the ship rose up abruptly from the water's edge, a dark rock, which at a distance, looks like a yawning cavern in the side of the island. A little to the right is seen a cluster of buildings and a church, which with their white plastered walls, have a very pretty effect, contrasted with the verdure of the fields. Far to the right is seen the island of Pico, with its lofty conical summit. Between this and Fayal, as I have before said, is a narrow channel, on the left hand side of which, just after rounding the high bluff on the south-eastern side of the latter, the town of Fayal opens before you, built upon the sides of several hills that incline towards the sea. Upon this bluff is a small fortification, garrisoned by Portuguese soldiers; and there is also another fort facing the harbor, which mounts nine or ten guns, of no very formidable charac- |

ter, as I should judge. The harbor of Fayal, the only one among these islands that offers any anchorage to ships, is but a mere indentation in the land, and is safe only with a westerly or northerly wind. These islands are subject to frequent and violent gales of wind, and during a storm from the south, the ocean comes rolling into the harbor in all its fury, oftentimes carrying away the stone wall that defends the town on the side of the harbor, constructed expressly to resist the violence of the sea. The harbor is very deep, and the ordinary chains of ships are insufficient to hold them in a gale of wind from the southward. There were one or two small, rakish looking vessels lying at anchor near the shore, and a fine large ship, standing off and on, with the American ensign flying at her mizzen peak. She proved to be a whaler, from Wilmington, Delaware, and soon came to anchor to repair her rudder, the head of which had been twisted off in a gale of wind. When about a mile from the landing place, we rounded to, and a boat was lowered to put the Captain and myself ashore. The wind was fresh and flawy, and by the time we reached the shore, we were all well sprinkled with salt-water. Fayal, like many other places, presents the best appearance at a considerable distance off. As you draw nearer and nearer, the beautiful white walls of the houses become more and more dingy, while the dark muddy looking wall rising up from the water's edge, gives to the town a peculiarly unprepossessing aspect. There are no docks, and but two or three landing places for boats. Articles of merchandize are transported to and from the shipping in lighters, which are small craft of ten or fifteen ton's burden. |

We pulled for the stone quay, which was crowded with a ragged, noisy multitude, all vociferating in a foreign language, which sounded to me like another "confusion of tongues." It has a strange effect upon the mind, when we hear for the first time a language we cannot comprehend, while our own becomes a novelty. Then we feel that we are indeed in the land of strangers. We were interrogated by the health officer, before we were permitted to land, as to "Where we were from–" "How many days out–" &c. The answers were satisfactory and we were allowed to pass. Our men in the boat, however, underwent a more strictly personal examination; for immediately after the health officer signified his satisfaction of the health of the ship, one or two men jumped into the boat, and commenced searching the pockets of the crew, to see if they had secreted any contraband articles, such as tobacco and soap. Not much of the latter article was found, as sailors on duty, do not often manifest an intimate acquaintance with this article, and the appearance of the men might readily have testified to the contrary. Of the other interdicted commodity, many a choice bit was reluctantly surrendered, although in each case a consolatory quid was cut off and given to the owner, for immediate use. On landing, we were received by the brother of the American consul, Mr. Dabney, who invited us to walk tip to his office, which is but a short distance from the landing place, and overlooks the harbor. After a short conversation with several American gentlemen about the news from the United States, Captain Richards and myself took a walk around the town. Near the consul's office is the fortification, facing the harbor, and in the rear of it runs the principal street |

of the city. Before the gateway stood several soldiers of the garrison, and we saw several of them in our ramble; they are tall, martial looking men, and their dark whiskers and moustaches have a very dashing appearance. Their uniform is blue, resembling that of many of our military companies at home. They wear upon their heads little blue caps, trimmed with red, and in shape resembling a truncated haystack. The entire number of soldiers upon the island, Mr. Dabney informed me, does not exceed seventy. Wherever we went, we were escorted before and behind by a troop of ragged boys of very questionable appearance. The streets of Fayal are extremely narrow. They are paved with large, flat stones, and are kept as clean as could be expected, considering the appearance of the population. The sidewalks are so narrow, that two persons cannot walk side by side, without danger of tripping one another. I was astonished at the immense burdens the porters carried upon their shoulders. They occupied the middle of the street, moving along under large casks or boxes, that seemed heavy enough to crush them. It took two men on board our ship to transport readily, a box of oranges, such as I saw individuals of them carrying upon their heads and shoulders. The heaviest work is performed by the labor of oxen, yoked to short carts with strong wheels; they are directed with a stout pole pointed with iron, which the driver, who walks just before them, thrusts against their ribs every few minutes, not appearing, however, to exceed in cruelty, the teamsters of our own country, whose wanton application of the lash to the poor patient ox, has often roused my indignation. We passed through one of the principal streets. The |

houses upon each side would be called three story buildings, although their actual height was about that of our two story houses. Before each of the upper windows are latticed balconies, painted green, in the front of which are small doors; some of these were opened a little, disclosing at one time, a fair female face, at another, the dirty phiz of some curious urchin. All the houses of Fayal are built of stone, and are whitewashed, which gives the city a very pretty appearance at a distance, as I before observed. The population is about five thousand, while that of the entire island is about twenty-eight thousand, as I was informed by Mr. Dabney. Our walk extended to the hospital, a large white building, fancifully ornamented with slate colored figures of every variety of curve. It is a three story edifice flanked by two wings, one on each side, extending as far as any regard to symmetry would permit. This large structure, the finest by far in the city, and well located upon a gentle hill, was formerly a convent; but during a popular insurrection a few years since, the priests were expelled; and the building appropriated as a hospital, and as barracks for soldiers. On that occasion, the numerous bells of the convent were all melted up for coin, with the exception of one which is suspended in one of the windows of the third story of the main building. I could hardly account for this singular taste, especially as the cupola of the convent stands close by, which one would suppose to be the most natural location for a bell. At the foot of the hill is a fountain, the waters of which rise into a cistern about four feet in height, supported by pilasters. The area of the cistern is about ten feet by four, I should judge; it is built of red sandstone, and must have supplied the inhabitants with water for some time, as it bears the date of 1680, |

sculptured upon one of the sides. Near the fountain reposing upon the stones of the street in undisturbed quiet, lay a meditative donkey, a sine qua non in all Spanish and Portuguese places. Many of the inhabitants were wrapped up in their cloaks, although the thermometer stood at 60°. The women almost universally, were seen dressed in large cloaks, some of them having capacious hoods attached. These cloaks were invariably of blue color, but of various materials, according to the rank of the owners; the "ton" of the city, sported their broadcloth cloaks of very ample folds. These garments, which with us usually indicate cold weather, are, I am told, worn also in the middle of summer. But what struck me as particularly ludicrous, was the huge bell-topped hat, that the fashionable ladies had adopted, which had at least the merit of being more easily adjusted to the person than the head-dresses worn by my fair countrywomen. A large white handkerchief is first arranged upon the head, and upon this these heavy hats tower up to a height endangering the neck of the fair owner. She, however, seems sensible of this, and is careful to keep the hat nicely balanced upon her head, while her handkerchief waving to the breeze, completes the costume of a Fayal lady. The motions of the ladies did not appear to me very graceful; they came swinging along half way between a trot and a walk, reminding me of the daughters of Erin, I used to see in New-Haven going to church. There are said to be some very pretty ladies in Fayal; but they did not, I am certain, make their appearance in the streets on the 12th of November. The lower class of men wore upon their heads little blue conical caps of cloth, or straw hats of portly, bell- |

topped dimensions and shape. Those in a better condition in life, were dressed similarly with people in the United States. When we returned to the consul's office, an English gentleman connected with the office, politely invited us to visit the consul's gardens, a proposal we were glad to accept. We were admitted to the premises by a private entrance, which led to the front of the house through a passage way between two parallel walls of twelve or fifteen feet in height, which were covered profusely with grapevines. It was in vain that I looked for the grapes I had been delighting my imagination with during our voyage; since the grape season had passed, and the withered leaves were all that remained upon the vines. We were shown one or two rooms of the house, that indicated the style of affluence in which the consul is accustomed to live. Then passing into the gardens, beautiful flowers met our eyes in every direction, and those that had faded before we left the United States, were here exhibited in full bloom. Roses and Artemesias of various kinds, I recognized as old acquaintances; while many varieties of flowers, that were quite new to me, perfumed the air. Many plants I noticed, were here growing in neglected luxuriance, that with us require the most careful treatment. Geraniums towered upward to the height of tall shrubs, while the hydrangea was scattered over the garden as one of the most common flowers. The hydrangea, as well as several other flowers, which with us are of a pink color, when transplanted to these islands, turns blue, and vice versa. The method of rearing the orange tree from the slip, was exhibited to us. An enclosure of tall reeds woven together surrounds the tender orange slip to protect it from the violent winds that frequently sweep over these |

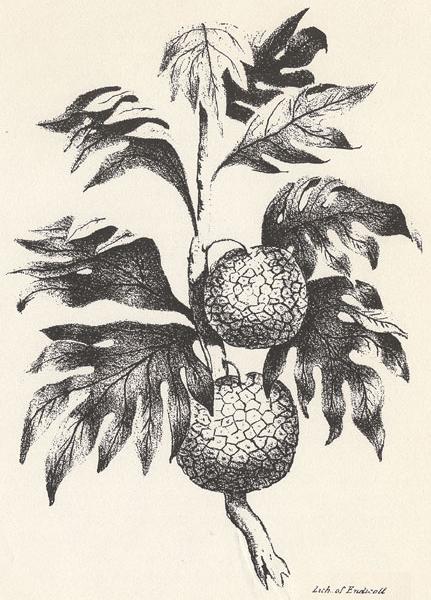

islands. In a year or two the young tree is enabled to resist the ordinary blasts that assail it. From this garden, itself of very ample dimensions, we were led through a tunnel under a street, into another of equal extent, filled with many varieties of tropical fruits. Orange trees, bending under the weight of their rich yellow burdens, citron and lemon trees, grew up thickly together like the trees of our forests; while the ear was charmed with the warbling of birds. The grape vines are trained upon arbors formed of the tops of parallel rows of young poplars entwined together. As I looked down the long arches, wreathed with prolific grape vines, and seeming to meet in the distance, and rambled on through shady arbors, with the coffee tree and the banana springing up around me, I could hardly believe myself sixteen degrees north of the tropic, in an inclement season of the year, and but about two hundred miles to the southward of New-England. The bananas were growing in an excavated hollow, a necessary protection against the violent winds. The stalk which bears the fruit is three or four inches in diameter and rises to the height of ten or twelve feet. Immense leaves of a rich, apple green color put out from the stalk, which, near the top, give place to the fruit, a single bunch numbering from twelve to twenty bananas. The banana when ripe, is of a golden yellow color and in size and shape, it very closely resembles the pod of the plant with us commonly called milkweed (asclepias syriaca). The rind is pulled off very readily, and discloses a luscious and mealy pulp of a slightly acidulous and astringent taste, with a few small seeds set thickly along in a longitudinal core. These gardens are situated upon an inclined plane above the level of the town, and command a delightful |

view of the ocean, and of the neighboring island of Pico. They are surrounded by a high stone wall neatly whitewashed, upon which vines of various kinds are trained. Returning towards the house, we were conducted into the flower garden, where were flowers of every variety, and rare shrubs evincing the taste of the proprietor, under whose personal superintendance all these gardens were laid out. On our way to the consul's office, we passed through a quadrangular yard in the rear of the office, surrounded upon three sides by large storehouses for wine, and ship stores of various kinds. Under the hands of the cooper were several huge casks made of Brazil wood, whose great size is said to be important to the preservation of this wine. Very little if any wine is made in Fayal; that consumed on the island, and exported to foreign countries is imported from Pico, upon the south side of which the grape vine is extremely prolific. It is called "Pico Madeira," and is very similar to that which with us bears the name of Madeira wine. At the consul's office, we met the master of the whaler that lay at anchor in the harbor. He was from Wilmington, Delaware, and had been out only about as long as ourselves, but had already met with a sad accident. In an attack upon a whale, the line as it shot out of the boat, became entangled around one of the men, and instantly carried him down, and the poor man could not be rescued until life was extinct. This is one of the dreadful casualties to which the adventurous life of the whaler is exposed. Were I inclined to make a digression, many a hair breath escape from death or mutilation might be related, of which I have heard from the mouth of those who have been active in these hazardous adventures. In the afternoon we were invited by Mr. Dabney to |

dine with him at his mother's residence in the upper part of the town. The family of Dabney is the most prominent for wealth and respectability of any on the island; and upon each side as we passed, hats and caps were raised in token of respect. As far as my observation extended, the people appeared to be very polite and respectful in their manners. Gentlemen in meeting or passing one another, raise their hats from their heads, and with a graceful wave restore them to their places. I was told by Mr. Dabney, that there is a prodigious wear of hats and caps among all classes, in the way of salutation. Whether this remark is to be taken in jest or in earnest, I thought that my fellow countrymen, with all their notions of economy, might advantageously adopt the custom. The elder Mr. D. is a graduate of Harvard University. It was delightful to meet with a man of his intelligence, especially one who had visited many places in America, with which I was familiar. Those that never move beyond the boundaries of their own country, do not know how welcome is the face of a countryman in a foreign land. We ascended the hill upon which the Hospital stands, and beyond it at some distance above, entered a gate leading to the house, through an alley overshadowed by the Sycamore tree, a great rarity at these islands. The house faces the eastward, and commands a magnificent prospect. Directly before us, the towering Peak of Pico, then veiled in clouds, limits our view in that direction; while between the two islands, the deep blue ocean is seen heaving its foam-capped billows, and extending to the horizon on the right. The grounds about the house are extensive, and still more beautiful than those of the consul. From the piazza, which reaches entirely across |

the front of the house, the garden with its orange and lemon trees, whose fruits were lying neglected upon the ground, and its verdant shrubbery, is spread out before you. We were soon ushered in to dinner, where we were introduced to Mrs. Dabney, mother of the consul, and to several other ladies, with whom we spent the hour very pleasantly. The dinner was excellent, and served up in good style, and it was peculiarly acceptable to me after my experience of sea fare during the past month. Immediately after dinner, we bade adieu to our very agreeable hosts, and hurried aboard the North America. During our absence, the various articles ordered by the captain and myself, were sent on board in the consul's lighter. Potatoes, oranges, apples, wine, fowls, eggs &c., can be purchased here at a much cheaper rate than at home. Of potatoes, one hundred bushels were added to about an equal quantity we had on board. More than two thousand oranges were purchased at the rate of $3,00 per thousand, for the use of the ship. The Fayal oranges are small, and rather sour, while the apples are sweet and insipid. I have been thus particular in enumerating our supplies, to exhibit the liberality with which whalers recruit wherever they stop for this purpose. Late in the afternoon we left Fayal, and endeavored to beat out to sea, but failing in this attempt, as there was a strong current setting in between Fayal and Pico from the southward, we fell off before the wind, with the intention of circumnavigating the island. At sunset, we were driving along under a close reefed maintopsail and foresail, before a heavy squall off the land. The wind was fresh all night, but the next day, (Wednesday,) we were out of sight of land, very much to our satisfaction, |

lying to in a gale of wind, with the head of the ship pointing to the westward. On Thursday, (Nov. 14,) with a fine breeze from the west, we altered our course for the south, and before night, we bade adieu to the hills of Fayal and the Peak of Pico, in sight of which we coasted during the day. On Friday and Saturday, with the wind astern, we made rapid progress southward, enjoying the fruits and "fresh grub" we procured at the islands. On Sunday and to-day, (Monday,) the wind has continued to blow steadily from the N. E., and we are feeling the first impulses of the trade winds, regular breezes within the tropics, which blow generally from N. E. to S. W. on the north side of the Equator and from S. E. to N. W. on the south side. This is the season of the year for the unusual display of shooting stars, which for several years past, since the grand exhibition of 1833, has excited so much attention among astronomers. Last Wednesday was the anniversary of this interesting event, and I had been looking forward to its recurrence with no ordinary feelings of interest, particularly as it had been enjoined upon me to make a careful record of what facts I might collect with reference to this phenomenon. For several days previous, the officers of the watch told me that they had seen an unusual number of very brilliant meteors. It was not until Wednesday, that I felt myself well enough to look out for meteors, and at an early hour I was upon deck, in eager expectation. How great was my disappointment on finding the ship lying to in a gale of wind, and the sky overcast with heavy clouds. On Thursday morning, I again made the attempt. It was a beautiful morning with a fine clear air; but the |

clouds that rose in quick succession and sailed across the sky, precluded all astronomical observation.* Although an exhibition of this wonderful phenomenon has been denied me, I have often pictured to myself the scientific excitement that has undoubtedly occurred at New Haven; and it has been to me a pleasing thought that though far away from home and friends, our minds are united in the same grand contemplations, and interested in the recurrence of the same phenomenon. Tuesday, Nov. 19. We are making rapid progress southward, and have arrived on the borders of the tropics. A fine, fresh breeze is impelling us forward tempered with the softness of a milder clime. Last evening, just after sunset, I saw a phenomenon of an entirely novel character to me. A bank of heavy clouds rested on the western horizon, and on its front a beautiful rainbow was set like a diadem. The moon was shining serenely in the eastern sky, which gave origin to this phenomenon. Captain Richards told me that he had very frequently seen these lunar rainbows, though not so often as the solar, but sometimes as brilliant even as the latter. * The Meteoric Showers of November, are supposed by my father to have ceased after 1838. ("Letters on Astronomy," p. 350.) |

CHAPTER III.SHIP AND SHIPMATES.

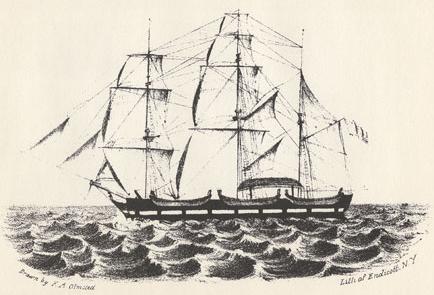

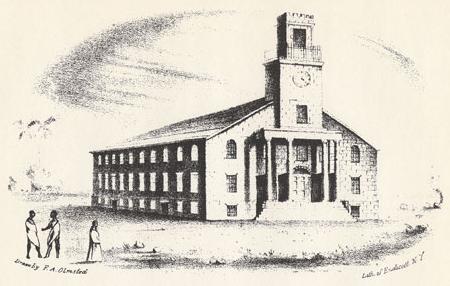

Before proceeding farther in my narrative, I will introduce the reader more particularly than I have yet done, to my ship and shipmates. It may be well also to explain the common maneuvres of a ship, and to describe its several parts at once, rather than to interrup the chain of my narrative by being obliged to stop frequently to render myself intelligible to the uninitiated. The North America, was built by Stephen Giraud, Esq., and was originally intended for a letter of marque during the last war with Great Britain. The war terminating before she was completed, she was applied to the merchant service and sent to the East Indies. About eight years since, she was purchased by her present owners, and converted into a whaler. She is an exceedingly strong vessel, with timbers of great size, and disposed rather more closely together than is customary in most ships of her tonnage. Her frame work is entirely of live oak, the best material for shipbuilding in the world. She is a very fast sailer, particularly "on the wind," and in working to windward has always had the reputation of being surpassed by no square-rigged |

vessel. Since leaving the United States, we have beaten every thing, although we have been under easy sail all the time. Whalers are navigated by more than the usual number of men for vessels of their tonnage. The North America measures 386 tons, and fifteen or sixteen men "all told," would be considered adequate for working her in the merchant service, whereas we carry thirty-one men for our complement. Each boat has a crew of four men, besides the boatsteerer and the officer who commands her. As we carry four boats in service, the remainder of the crew work the ship, when the boats are in pursuit of whales. Some whale ships carry five boats in service, with a complement of forty men, and some but three, with a proportionate number. The management of the ship rests with the captain and his officers. The supreme power is vested in the captain, and it is absolute, extending not only to the sailing of the ship and her internal economy, but also to the conduct of every one on board. He exacts the most scrupulous respect and deference from his officers and men, and quickly reprimands or punishes any infraction of the etiquette, which long usage has established. He has the power of turning an officer before the mast, and substituting one of the men in his place, if he is dissatisfied with his conduct. The comfort of the men depends almost entirely upon the will of the captain. If he treats them with kindness, their lot is comparatively happy; if he is tyrannical and abusive, the ship becomes a miniature purgatory. In case of mutiny, the captain would be justified at law, in shooting down any of the mutineers, or in using any coercive measures to compel them to return to their duty. The captain and his officers take observations daily, if |

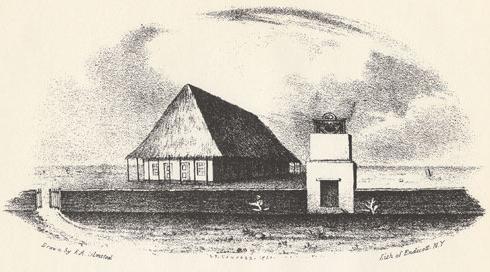

Barque NORTH AMERICA - New London |

the weather permits, to ascertain the position of the ship, and it is the duty of the former to mark down her daily progress upon the chart, a large scroll, upon which the shores of continents, islands, rocks, shoals &c., are accurately laid down in latitude and longitude. A ship's position on the globe, is known when her latitude and longitude are known. These are calculated by two methods, – by dead reckoning, which proceeds upon trigonometrical principles, and by observation of the heavenly bodies; the latter is preferable, as it is the most exact in its calculations. Finding a ship's latitude by observation is a very simple problem. The Sun's altitude at noon is taken, and by a few calculations you have the latitude. The longitude is obtained by taking an altitude of the Sun before noon or after noon, from which the exact time of day is ascertained, and then by comparing this time with the time at Greenwich, you have the longitude. That time is known from the chronometer, an extremely accurate timepiece adjusted to correspond to it, and carefully wound up so as to preserve the true Greenwich time. The necessity of extreme accuracy in the movement of these instruments will be readily seen, when it is recollected that an inaccuracy of four seconds will make an error of a mile in the supposed position of the ship. Hence it becomes very unsafe to rely upon a chronometer entirely, and the prudent navigator takes other observations every little while to rectify his chronometer; for if he can only ascertain its rate of going or amount of error, he can depend upon it without hazard. In this case, he resorts to the more careful and delicate observation of measuring the distance between the moon and the sun by the sextant, while his officers are taking altitudes of the the Sun and Moon at the same instant, and |

some one is noting the time by the chronometer. From these observations, the position of the ship is ascertained by two independent methods, and the correctness of the chronometer tested. The astronomical instruments made use of are the quadrant and sextant, the former used on common occasions for determining the latitude, and the latter when great delicacy of observation is requisite. The captain stands no watch, but exercises a supervision over all, to see that they do their duties. Several times during the night, the officers make report to him on the progress of the ship, the appearance of the weather, and any unusual occurrence. The captain also presides at table, and gives orders to the steward about every thing that comes upon the table, as well as about the distribution of provisions among the ship's company. He seldom has any conversation with the men; all his commands are issued to them through his officers. The most arduous duties aboard the ship, devolve upon the first mate. It is his duty to attend to the reception of all the stores that are put aboard the ship, and he also keeps the log-book, a kind of Journal in which are registered the progress of the ship every hour, her position in latitude and longitude, remarks on the weather, &c. When all hands are called, he takes his station with his watch upon the forecastle, and manages the head sails, lets go the anchor, and sees that every thing "alow and aloft," is "shipshape." The second mate with the starboard watch, is stationed in the waist of the ship to work the main and after sails, while the third mate belongs on the forecastle. The second mate of a merchantman is not usually respected very highly; but the second and third mates of a whaler, having another grade of rank intervening between themselves |

and the foremast hands, are treated with much greater deference. The next in rank are the boatsteerers, of whom one is attached to each boat, whose duty it is to keep the boat and all her appurtenances in complete order. They are also frequently sent off in charge of their boats to execute some command for the captain or officers, and are very ambitious to make a good appearance before the other men, or else they will not be respected. All whaleships carry a cooper, a carpenter, and a blacksmith, whose respective duties will be understood without my descending to particulars. Our crew is composed of rerpresentatives from a variety of nations. Besides the Americans, there are three Indians, one Englishman, six Portuguese, and several colored gentry, that claim to be Americans. One of the Indians bears the renowned name of John Uncas, and is a lineal descendent of the celebrated Sachem of the Mohegans. He is a very active intelligent boy, and will become a first rate seaman. Our cook and steward belong to the ebony race; the former, "Mr. Freeman," as he is often designated, is the most comical character I ever met with, and I cannot refrain from adding a tribute to his memory, as he is the fountain of all the fun and good humor aboard the ship. In this respect, he sustains a relation to the ship similar to that of the jester in a feudal establishment; and although the captain and officers would consider it impairing their dignity to descend to any familiarity with the men, yet "Spot," is regarded as the privileged character on board, and the discipline is not relaxed by any amusement at his expence, which the captain and officers choose to indulge in. He receives a serio-comic punishment from the captain and officers every day, when his |

grimaces and exclamations are so ludicrous that I am sometimes almost faint with laughing. We call him down into the cabin now and then, and give him presents, to amuse ourselves with his elegant bows and expressive exclamations of satisfaction. He possesses all the negro accomplishments in full perfection, embellishing his conversation by the use of language in all the variations of which it is susceptible. He can sing a song, play upon the "fiddle," dance various jigs "on the light phantastic toe," and roll up the white of his eye – all in the genuine negro style. I have witnessed the exhibitions of many extravaganza performers, but I think they were surpassed by our cook with his various appellations of "Spot," "Jumbo," "Congo," "Skillet," "Kidney foot," &c. Among his other good qualities, he is extremely polite, and bids me "good morning," with a very graceful bow; and if I consult him about the weather, when the clouds indicate a favorable change, he takes a very wise look around in every direction, and predicts, that "we are going to have some very plausible weather, so far as the aspection of the sky would seem to elucidate." He is frequently summoned into the cabin, and soon makes his appearance on deck, with his capacious mouth distended to its utmost limits, with oranges, apples, and other things, which have been thrust into it. The steward takes care of the ship's stores, and distributes the provisons according to a bill of fare given to him by the captain. His appearance also partakes of the comical, especially when he waits upon table in the cabin, when his lank, ebony visage, and long limbs, remind me of the India Rubber men I have seen in shoe-maker's shops at home. He is a very important personage among the men, however, especially with those who are looking anxiously for a stray bit from the cabin table. |

The cook with his "fiddle," and the steward with his tambourine, hold musical soirees on the forecastle every evening in pleasant weather. Whatever may be thought of the performances of these sable musicians, they are sufficient to excite the activity of all that are disposed to dance. There is a mysterious connection between the vibration of a fiddle string and the vibrations of the heels. For as soon as the sound of the violin is heard, then commences a general patter upon deck of all the excited. The dancing of sailors does not require a knowledge of the fashionable figures; all that is necessary, is to keep time with the feet, and to beat the deck with a suitable degree of vehemence. Simple as this sport may appear, it serves happily to diversify a sea life, and I frequently go forward to amuse myself with the curious maneuvres exhibited, and the good humor that prevails. At eight bells, (eight o'clock,) all "sky-larking," or amusement instantly ceases, and all hands disperse, some to their berths, and others to their duties upon deck. The men as I have before said, are divided into two watches, the larboard and the starboard, who keep watch upon deck alternately for four hours at a time. The watches are regulated by the bell, which is struck four times at every half watch, when the wheel is relieved as well as the look-outs at the mast-heads; and eight times when the watch is out, and the other half of the crew come upon the deck. In most ships I believe it is customary to strike the bell every half hour. There are certain forms of respect that are never deviated from aboard all vessels where discipline is observed. The foremast hands never come aft, unless they have business which calls them there, and then they always take the lee side of the ship, and any "sky-larking" upon the |

quarter deck, would be severely punished. If a sailor has occasion to go into the cabin upon any duty, he is careful to leave his hat upon deck. It is an important object to keep the men always employed during their watch upon deck, and their duties are performed with regularity from day to day. At daylight, commences the scrubbing of decks and washing down fore and aft. This is done by the watch upon deck, who with their heavy "scrub brooms," and common brooms, wash and scrub the decks until they are perfectly clean. Sometimes soap and sand are used, as often as once every day or two. When this duty is completed, the mastheads are manned, and at half past seven o'clock, breakfast is served up, immediately after which, the carpenter, blacksmith and cooper, are engaged in their respective avocations, while the watch is employed upon an old sail, picking oakum, making spun yarn, &c. No one is allowed to be idle, and every thing proceeds with a regularity, which people in general, from a misconceived antipathy, are not willing to credit in a whaleman. As was originally proposed, we will now describe the different parts of the ship, and the peculiar constuction of a whaleship. In the accompanying diagram is a representation of the North America, on the wind, with the larboard tacks aboard,* and the reader is requested to compare the following description with the picture. From the bow of the vessel, projects the bowsprit, from the extremity of which extends the gibboom and flying * The reason assigned by Jack, for giving the pronoun relating to a ship, the feminine gender, is rather amusing, and somewhat discourteous to the fairer portion of creation. Says Jack, "the reason why we call a ship a she, is because her rigging costs more than her hull;" an opinion, to the truth of which, I hope I shall not be considered as certifying. |

gibboom in one stick. The foremast rises upon the bow, the mainmast in the middle, and the mizzenmast in the aftermost part of the vessel. The supports of the masts upon each side, are denominated swifters and shrouds, and united in the tops, semicircular landing places, about nine feet wide, at right angles to the fore and mainmasts. That which corresponds to them on the mizzenmast is called the mizzen cross trees. The next upper divisions of the mast are called topmasts, as the foretopmast, &c. They are supported like the lower masts by headstays, shrounds and backstays. The next upper divisions are the top gallant masts, and the next the royal masts, terminating in a ball called the royal truck. The landing places above the tops are denominated cross trees, and are named from the divisions of the mast to which they belong, as the foretopmast-crosstrees, the maintop-gallant crosstrees. The men sent aloft to look out for whales, are stationed in the topgallant-crosstrees. Upon the extremity of the flying gibboom rises the flying gib; next to this, and nearer the vessel is the gib, and next comes the foretopmast-staysail, a small triangular sail, used principally when the ship is "lying to" in a gale of wind. Upon the foremast are the foresail or forecourse, foretopsail, foretopgallant-sail, and some ships carry a foreroyal. Upon the mainmast, are the mainsail or maincourse, &c. Ships sometimes carry a sail above the royal, called the skysail, and sometimes, though rarely, a sail above this called a moonsail. These "light kites," however, are of but little use, and it would be much better to enlarge the royals and dispense with them altogether. Vessels, in going with the wind free, frequently carry temporary sails upon one or both sides of their topsails, topgallant-sails, and royals, called |

studding sails. The largest sail upon the mizzenmast is the spanker, above which is the gaft-topsail; between the mizzenmast and mainmast, are seen two triangular sails, the lower one of which is named the mizzen staysail, and the upper the mizzen topmast-staysail. There are several other sails that ships sometimes spread, though rarely, which I will just enumerate, as, the gib of gibs, gib topsail, fore and main spenser, ringtail and water sail. The yards, are the spars upon which the square rigging is distended, and receive their names from the sails "bent" upon them; they are brought to any required angle with the length of the ship by means of the braces attached to the yard arm, and worked upon the deck. The halliards, runners and ties, elevate the yards upon the upper masts. The sheets are those chains or ropes that draw down the ends of the sails to their proper places. The reef points are short ropes about two feet long, arranged in rows upon each side of the larger sails, and are used to diminish their size. There are in the topsails three rows of reef ponts, and a ship is said to be under single, double or close reefed topsails, according as one or two or three reefs are taken in these sails. A sail is clewed up, when the extremities of its foot or lower edge are drawn up to the middle of the yard. There are many ropes used in working the sails, such as clewlines, buntlines, bowlines, and reeftackles, which it would be tedious to explain. A ship is said to be "in stays," when the wind is ahead, in a line with the masts, when after receiving the wind on one side, she is endeavoring to come around on the other. The wind is "abeam," when at right angles with the length of the vessel; "upon the quarter," when it comes aft, but not in a line with the length of the ship. |

We will now come down from aloft upon deck.* Between the mainmast and foremast are the tryworks, large furnaces built of bricks, and containing two immense iron pots, for trying out the oil from the blubber. The flames and smoke escape through several openings in the top of the works. Between the mainmast and mizzenmast is the "galley," a little kennel large enough for the cook and his stove, but a mystery to all ambitious housekeepers with capacious kitchens, how so much, and such a variety can be cooked in so small a compass. There sits Jumbo, in sooty dignity, superintending the steaming coppers, and reflecting upon the responsibility of his station, while the hot liquids are scattered around, and perchance fly upon his unshod extremities, as the ship rolls heavily in a cross sea. In some ships, the galley is set forward of the foremast. Above the galley is a framework of spars, called "bearers," upon which the spare boats are turned bottom upwards. In the aftermost part of the ship, are the wheel and the binnacle, containing two compasses, by which the course of the ship is regulated. Abaft the mizzenmast is the companion way leading into the cabin, appropriated exclusively for the captain and his officers. The cabin contains six staterooms, a storeroom and a pantry. A state-room aboard a ship, places a man in rather contracted quarters. One very soon becomes used to it, and I feel as contented in my little bandbox, measuring not more than six feet one way and four feet the other, and receiving light through thick ground glass set in the deck, as I should in a palace; and I can sleep as comfortably in my berth with Looking towards the head of the ship, the right hand side is called the starboard, and the left hand the larboard. |

its coffin-like dimensions, as upon the finest bed; much better too, for I am now prevented from rolling about in the pitching and tossing of the ship. Just forward of the mizzenmast is the steerage, covered over with a box having a slide upon it, called the "booby-hatch," a peculiar designation not applicable to those who live in the steerage, as they strenuously contend; for here are located the boatsteerers, carpenter, cooper and blacksmith. In some ships, all the steerage men take their meals in the cabin after the captain and officers have had theirs, but it is not the case with us. Forward of the foremast, is the forecastle, a receptacle for sailors, where twenty-one men are stowed away, in a manner mysterious to those who have never visited this part of the ship. The forecastle of the North America is much larger than those of most ships of her tonnage, and is scrubbed out regularly every morning. There is a table and a lamp, so that the men have conveniences for reading and writing if they choose to avail themselves of them; and many of them are practising writing every day or learning how to write. Their stationery they purchase out of the ship's stores, and then come to one of the officers or myself for copies, or to have their pens mended. When not otherwise occupied, they draw books from the library in the cabin, and read; or if they do not know how, get some one to teach them. We have a good library on board, consisting of about two hundred volumes, and a good proportion of sperm whalers are also provided with them. Sailors, as a general thing, are ready to avail themselves of any opportunity for mental improvement; and I have no doubt the efforts of the benevolent in supplying ships with good books and tracts, will be attended with great success. Notwithstanding the immorality that is to be so much |

deplored among seamen, they have generally a respect for religion and its observances. It is very gratifying to take a look at the forecastle upon the Sabbath in pleasant weather. Perfect stillness prevails aboard the ship; no loud talking is allowed, while the "people," after washing and dressing themselves neatly, are seated around the forecastle, or upon the windlass, poring over the Bible or some tract.* We have a good medicine chest on board, which I believe to be the case with a majority of whale ships. To provide for wear and tear of clothes during the long voyage, a large assortment of garments of every kind is put on board, to be sold to the men as they may need, at a slight advance upon the original cost, after the expiration of one year from the time of sailing. These are denominated "slop chest" clothes. Were perfectly fair dealing observed in all cases towards the men in the management of the "slop chest," one of the most prolific sources of discontent aboard whale ships, would be entirely removed. The men as they ship for the voyage, are told that they need not trouble themselves about any preparations, as every thing they may require, can be purchased out of the "slop chest" after they get to sea. Upon applying for necessary clothing after they are separated hundreds of miles from home, they find that every article they ask for, is indeed in the slop chest – but to have it, they are to be charged a most exorbitant profit on the first cost, so that all their hard earned wages are * My situation as passenger, enables me to extend to the crew many acts of kindness which the stern discipline of the ship would hardly permit in an officer, and their gratitude is manifested by their avidity to oblige me whenever any occasion presents itself, and to exhibit other marks of regard. Whenever in my rambles about the ship, I go forward, their looks indicate that I am no unwelcome visiter. |