|

Frederick Debell Bennett 1806-1859 Notes |

|

LONDON:

J. B. NICHOLS AND SON, 25, PARLIAMENT STREET. |

Pitcairn's Island

|

CONTENTS OF VOL. II.

| |||||||

| ||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

30°40 to 30°60, which last was the highest it marked during the entire voyage. Dec. 10. – In latitude 24° N., long. 115 1/2° W., numerous shoals of bonita, albacore, and skipjacks, (Saltatrix, Catesby,) came around us; several turtle also made their appearance; and the sea was covered with a large quantity of the sea-weed named porra by the olden Spanish navigators, who were accustomed to regard its presence as an indication of their vicinity to the coast of Mexico. At daylight on the morning of the 12th, land was unexpectedly seen from the deck of the ship, bearing N.N.E., distant thirty miles. It proved to be a group of three islands, extending in an east and west direction, of moderate size, elevated, rocky, and apparently barren. By our observations, this group lies in lat. 24° 9' N., long. 112° 39' W. – a spot where no land is laid down in any of our charts. An ordinary map of North America, of 1814, places islands in the vicinity under the name of Celisos;* but it is more than probable that this group is the Lobos (or Seal) Islands, laid down in Krusenstern's and in Arrowsmith's charts 150 miles to the N.N.W. of the position above assigned. * Probably a corruption of A lejos, signifying "in the offing" or "afar off." |

These islands are so perilously placed for shipping making Cape St. Lucas from the northward, (a route annually followed by numerous South-Seamen,) that it is surprising they should have remained so long unnoticed, or their position undetermined.* That we failed to observe them during our passage of the preceding year, arose from our having then hauled up for the American continent much more to the southward than on the present occasion. On the following day the dark and elevated land of the N. American continent was seen from the mast-head, bearing E. by S.; and on the morning of the 15th we approached that coast within eight miles, and hove to between Cape St. Lucas and Cape Palmo, (the southern extremity of the peninsula of California,†) off the mouth of * Upon our subsequent arrival at Cape St. Lucas we were informed, that the existence of this group had been reported there by a brig, trading on the coast, and that some small vessels in quest of fur-skins had attempted to visit it, but without success. Judging from the appearance of the island, it is very probable that the fur-seal abounds on their shores. † Discovered by Cortez, the conqueror of Mexico, in honour of whom the gulf or strait was formerly named. In the year 1578, Sir F. Drake visited this peninsula, and (with the sanction of the sovereign chief of the whole country) took possession of it for the British crown. But |

a bay, corresponding to a small grazing settlement. Upon landing here we were kindly received by the inhabitants, and hospitably entertained by them during the two days we were engaged in receiving beef on board the ship, and salting it for sea-stock. This bay is situated on the N.E. side of Cape St. Lucas, and is extensive; but affords anchorage only on its eastern side, in about seventeen fathoms water close to the shore, and lies exposed to S. E. gales, which occasionally (and chiefly in the tempestuous summer months) invade its shores with great severity: the sea inundating the lowlands and leaving permanent traces of its inroads. Its beach is sandy, and washed by a long surf; but landing from boats may be safely effected. The tide on the coast is regular, with a rise and fall of six feet. The level plain that opens upon the bay is about thirty miles in length by ten in breadth, and entirely composed of a fine silicious sand, covered with a dense jungle. The mountains that enclose it are of white and red granite, and clothed with a cheerful verdure. The entire plain is one estate, which was originally possessed this claim was never vindicated by Great Britain; and, until the late war of independence, California, with the annexed coast of Mexico, remained a possession of Spain, by the right of discovery and conquest. |

by a Spaniard, who obtained it from the Mexican government by the payment of twenty dollars, and held it at a rent, or tenure, of one dollar per annum. He applied it to the purpose of an estancia, or grazing-farm, for supplying bullocks to the numerous South-Seamen frequenting this coast. Since his death, the management of the estate has devolved upon his son-in-law, an American, named Fisher. The village or settlement consists of about eight dwellings, erected at a distance from the sea, beneath the shade of some mimosa trees. They are small, built of adobes, (or unburnt bricks,) and thatched with flags, obtained from the neighbouring town of St. Jose. Each hut usually contains one or never more than two apartments; and is faced with a portico, which affords a favourite lounge for the resident family. Their furniture is scanty, and rather more useful than ornamental. The hairy surface of a dried bullock's hide, spread on the hard earthen floor, is the usual bed; and the tables and benches are very rudely constructed. Beneath the portico are deposited dried or tanned hides; the horse-furniture of the farmers, including the cumbrous but luxurious saddles, saddle-bags, (capable in themselves of containing a horse-load,) and spurs of murderous length; whilst on lines passing across |

the roof, are suspended cows udders or tongues, and large pieces of beef undergoing the process of jerking. Some sheds, distinct from the dwellings, are used for cooking, or preparing cheese; and an extensive range of corrals, or cattle-pens, contain at night the milch-kine and goats. The residents consist of about thirty persons, who, together with the occupants of other and similar farms scattered on the contiguous coast, form a motley population of "old country" and creole Spaniards; Spanish half-castes, or cholos; and native Indians. Nor does this small community furnish any exception to the rule, that there are but few habitable parts of the world which do not contain a subject of Great Britain or of the United States of America. The creole Spaniards (or those born of parents from the mother-country) do not differ in appearance from their European progenitors: the women, who seldom expose themselves to the sun, have fair and even ruddy complexions. The cholos, also, (when but slightly tinged with Indian blood,) are sufficiently fair; while their features are rendered mare softened, pensive, and pleasing, by an admixture of native traits. The costume of the women is neat, and as light as the climate demands. It is comprised in a chemise garment of white cotton, and a |

short striped-cotton petticoat. Their hair is simply parted on the forehead, and descends over the shoulders, braided in an elaborate and becoming manner. The men wear a cotton shirt, open at the neck, breeches loose at the knees, (to facilitate equestrian exercises,) a broad-brimmed straw hat, and shoes and buskins of rudely-tanned leather, well adapted to protect their legs from the thorny plants of the country. Some of the men wear their hair short; while others have it braided into a queue and pendant over the shoulders, after the manner of the women. A large woollen rug, white striped with blue, worn over the shoulders or enveloping the entire person, they more capriciously assume, and chiefly when on their journeys. Since the character of the soil offers no inducement to agricultural pursuits, these people confine their attention to rearing cattle, which, together with the cheese they prepare from the milk of their herds, form the staple commodities of the settlement. As we had been accustomed among the Polynesian islands, to notice a race of people living almost solely on a vegetable diet, so here we found another subsisting as entirely upon animal food: the only vegetables they consume being maize, (which they procure from a distant part of the country,) and |

a few small and indifferent sweet-potatoes, which they rack their own soil to produce. No rivers are to be found on this spot, nor any natural supply of fresh water, beyond a few ponds filled by the periodical rains. The inhabitants draw their supply of this essential from wells sunk in the sands, which produce good water at a very inconsiderable depth. The sale and use of ardent spirits is interdicted by their social laws; but they nevertheless indulge occasionally in a kind of rum or aquadiente, distilled from sugar-cane, grown in the inland parts of the country. Notwithstanding their monotonous, and highly animalized diet, these people are healthy, active, and robust: their only endemic diseases are agues, which they contract from the malaria arising from the jungle, soon after the termination of the rainy season. They live contented, and consequently happy; and their conduct towards each other, as well as to ouselves, was equally courteous and hospitable. The women are notable and modest. The men are expert equestrians, and excel in the use of the lasso.* It is a curious fact, that the * A strong and flexible rope of neatly-twisted hide, with a noose at one extremity, to cast over and entangle wild animals, while the other end is fastened to the saddle of the horse. The more correct orthography is lazo, a Spanish word, signifying a slip-knot or noose. |

women, whether creole Spaniards or half-caste, cannot be prevailed upon to eat with the men: a prejudice which must be regarded as of native or Indian origin, and one which coincides in a remarkable manner with the primitive custom of the Polynesian tribes. We noticed here also, an interesting Indian boy, about seven years old, whose only clothing was a girdle of cloth, whilst his features, complexion, and figure, accorded so closely with the Polynesian characteristics, that it would have been impossible to have detected him as an alien amidst an assemblage of Society Island youth of the same age. The Spanish language is universally employed by this people. They profess the Roman Catholic religion; and receive occasional pastoral visits from the padre of the neighbouring town of St. Jose; but of any literary acquirements they are ignorant to the extent of perfect bliss. At a very early period after its discovery, a Spanish Jesuit mission was established on the peninsula of California, and supported by supplies from the parent society at Manilla: the richly-freighted galleons, passing annually between the latter country and Acapulco, being instructed to touch at Cape St. Lucas on their way, to learn from the residents if their further |

progress was free from the danger of enemies' ships. The Jesuit missionaries would appear to have performed their duty with assiduity and success; the native Indians, with the exception of a very few tribes, having adopted in a great measure the language, religion, and habits of their civilized teachers. The objects of this mission having been considered as effected, the establishment has ceased to exist, and the spiritual charge of the mixed population is now entrusted to ordinary priests, as amongst the Roman Catholic nations of Europe. The commerce of the residents at the Cape is nearly confined to the English and American South-Seamen, that call there for supplies, and from which they procure the foreign manufactures they require, in exchange for the produce of their farm. The nominal price of a bullock is from three to ten dollars; cheese two dollars the 20 lbs.; turkeys a dollar and a half each; and other provisions in proportion; but the difficulty they find in procuring foreign merchandise, excepting at the exorbitant prices of the Spanish-American market, as well as the profit they derive from vending contraband goods at the town of St. Jose, or annual fair at La Paz, makes them anxious to trade in kind with the vessels they supply. When foreign |

ships are known to be hovering on the coast, an officer from the custom-house of St. Jose is stationed at this grazing settlement to prevent the contraband introduction of foreign goods; but this Cerberus is always greedy for a sop, and is himself seldom averse to doing a little in the way of free trade. To ships in want of essentials this port offers some advantages; but is not remarkable for the abundance or variety of the supplies it affords. Wood and water may be obtained by purchase, conveniently, and in sufficient quantity; and when a ready market is promised, the residents bring from the interior of the country an abundance of musk- and water-melons, oranges, bananas, pumpkins, and other fruits which their own sterile soil denies. The excellent beef also that can be obtained here, proves invaluable to South-Seamen when their stock of salt provisions is exhausted, and often enables them to make a much more protracted stay in the Pacific than they would otherwise be enabled to do. The oxen found here do not differ essentially from the European breed. Their average size is perhaps less; and their prevailing colour black, or black and white; they all, except the milch kine, rove unrestrained through the jungle of the plain, or browse on the declivities of the |

mountains, as the temptations of pasture may induce them. When any are required for slaughter, the owner, or his herdsman, (gaucho,) rides in pursuit of them, and casting his lasso over their horns, brings them captive to the settlement. Their meat is exceedingly well flavoured; and this may in some measure be attributed to the quality of their food, which is chiefly a herb, a species of Chenopodium, bearing tall, plumy, and fragrant flowers, and which covers the soil in sufficient abundance to supply the place of a grass pasturage. When the residents have more beef than they can immediately consume, they cut it into broad slices, and expose it to the sun until it becomes dry and hard; in this form, or, as it is usually termed, jerked, (a corruption of the Spanish word charqui,) it remains unchanged for a long time, and if well packed is very eligible as a seastore. The other domestic animals are horses, of a breed more remarkable for bone than blood, but which are tall, active, and docile; goats, which are numerous, and sold at low prices and swine, which are but few, and, from their foul-feeding, held in little esteem. Amongst the more remarkable quadrupeds, ferae naturae, that obtain on this coast, we find the puma, or American lion; the only large |

feline animal the New World affords. It is seldom this creature visits the settlement at Cape St. Lucas, though he holds his lair in its immediate neighbourhood, amidst the bush of the plains, or, more commonly, on the surrounding heights. The residents relate many instances of his attacking man, and even human dwellings. But a short time before our visit to this place, a woman, residing in the settlement, had left her house at night to draw water from a well,, when, finding in her path a deer, which had been recently killed by a puma, she imprudently took possession of the carcase and drew it into her hut. The puma returned soon after to his prey, and scenting the spot to which it had been conveyed, broke through the thatch roof of the dwelling, and before he could be put to flight destroyed two children and lacerated the woman severely. An Indian, also, employed on a farm, distant about fifteen miles from the bay-settlement, had recently been attacked by a puma while he was at work in the jungle. The man defended himself courageously with a knife, and succeeded in destroying the savage beast, but subsequently fell a victim to the injuries he received in the conflict. Notwithstanding these accidents, the people have but little dread of this creature; and pursue their journeys through |

the country both by day and night, often sleeping in the bush in the wildest districts, without any apprehension of its attacks: they describe it, indeed, as pusillanimous – more prone to shun than attack mankind – and ascribe its occasional attacks to a state allied to madness. The strong dogs of the country attack the puma with much animosity, and when the latter animal finds his affairs in an unfavourable condition, he ascends a tree, and from its height watches his yelling foes beneath. While his attention is thus directed, an Indian will sometimes contrive to cast a lasso round his neck, and, fastening an end of the thong to the tree, twitch him from the bough, and leave him hanging, strangled by the noose. Several kinds of deer frequent the dense and more sequestered thickets. One of these, which we encountered in the depth of the jungle, was a beautiful creature; in size rather larger than the fallow deer; the livery a pale iron-gray; the face marked with black spots on a pale ground the head adorned with a noble pair of tall and spreading antlers. Many young fawns, also, which had been captured, were running about the houses of the settlement, perfectly tame. The hares we noticed here were much larger than those of England; their ears are of |

extraordinary length and breadth, and their livery gray, like that of our common wild rabbit. The skunk, (Viverra putorius,) is commonly found in the vicinity of the settlement; squirrels frolic in the highest trees; and many bats, of small size, flit in the evening twilight. The birds most conspicuous near the settlement are vultures, or "turkey-buzzards." One of the two most common species has the general plumage brown-black; the under surface of the wings silver-gray; the head and upper half of the neck are naked, and of a bright scarlet colour; the head bears a resemblance to that of the domestic turkey, and the legs and feet (which are white) approach nearer in appearance to those of the gallinaceous than predaceous tribes of birds. The other, and more numerous species of vulture, is much larger than the last-described. Its plumage is brown and white, and with the exception of a naked and scarlet space on each cheek, its head and neck are entirely clothed with feathers. These birds are usually perched on commanding heights, watching for prey; and during the butchering of an ox attend in vast flocks to devour the offal: their utility as scavengers (in which duty they are assisted by some carrion-crows) amply compensating for their foul habits and disgusting |

familiarity. Wild pigeons, of the ordinary blue colour, are also abundant. At certain seasons of the year they resort to the sea-side in large flights to drink the salt water, and at any time a little grain, sprinkled on the soil, brings them together in sufficient numbers to afford the sportsman a massacre upon an extensive scale. The amphibia of the jungle are lizards, and many kinds of snakes, some of which are innocuous, and others highly venomous; of the latter, rattle-snakes are particularly numerous. The most valuable fish in the waters around the coast is the rock-cod, which at particular seasons arrives in large shoals. From amongst the turtle that float to these shores, the residents occasionally capture the hawk's-bill species, (testudo caretta,) from which they procure some good tortoise-shell. On the rocks in the vicinity of the Cape we find a great abundance of those elegant univalves, the California- or ear-shells, (haliotis.) The fish they contain have the habits of a limpet, (patella,) and are a very palatable food. Although the soil of this bay-settlement bears from the sea a desolate and barren aspect, and is, in an agricultural point of view, literally sterile, yet in none of the more luxuriantly wooded lands we had before visited had we |

found a spot which for variety and beauty of vegetation could compete with this. Foliage is certainly not profuse; and the style of vegetation is nearly allied to that which obtains at the Cape of Good Hope; but the abundance and beauty of its flowering plants, the novel forms of growth they often assume, and above all, the active juices and rich aroma possessed by almost every herb and tree, present a perfect picture of tropical botany. I could not but ask, if such was the desert – the mere land's end – the beach of the country – what must be the botanical productions of the inland and more fertile districts? Truly we might say to this spot – "Thy very weeds are beautiful, thy waste That any vegetation should exist on a plain of parched and dusty sand is remarkable; yet not only do trees of respectable height and girth, and often of luxuriant foliage, flourish on this tract, and a dense brushwood occupy the intervening space, but even the lowly and moisture-loving mushroom occurs in more than one spot, rearing its head, in full and juicy flesh, above the arid soil. On the whole it was evident that, notwithstanding the dryness of their surface, the sands had absorbed a great |

quantity of water during the annual rains, and which they return by evaporation from their depths, in the drier seasons of the year – scantily, it is true, but yet in sufficient quantity to support vegetation; while the succulent character of the leaves, and bulbous form of the roots of the greater number of the plants, tend much to economise their supply of moisture. To the botanist this spot alone offers a rich field for useful exertion: amongst more than seventy plants collected during our short stay, the majority prove to be new species, and several must be regarded as new genera. The more abundant, or conspicuous vegetation includes some splendid examples of the Cactus family. One of these is peculiarly conspicuous on the plains, rising in an erect and columnar form to the height of fifteen or twenty feet; its sides deeply fluted, (the angles armed with clusters of black thorns,) and its summit ramifying scantily. Some of the more aged examples have a bole four feet in circumference, destitute of thorns, and covered with a smooth white bark – the leaf in this stage of growth assuming the decided character of a caulis, or trunk. We observed neither flower nor fruit in this species. A vegetable column of this description, rising isolated in the midst of the |

plain, with a vulture perched motionless on its summit, had much the appearance of a highly-wrought zoophoric. A second many-sided cactus resembles that last described, in the form of its stem or leaf, but has a procumbent and diffused growth, and bears a profusion of flowers with broad and elegant rays of white petals, succeeded by fruit, the size and shape of a large orange, green when immature, and when ripe of a bright crimson colour. Within the rind, (which is dense and leathery,) is contained a red, juicy, and farinaceous pulp, studded with small black seeds. This berry is called by Europeans the "prickly plum." It is produced in great abundance, and its pulp (which has a cool, sweet, and subacid taste, not unlike that of a raspberry preserve) is an exceedingly wholesome and delicious food. A third species, resembling Cactus tuna, is the most common in the jungle, where its long and rigid thorns prove very troublesome to the traveller, penetrating his flesh, and resisting extraction by the barbed structure of their points. The species with broad and spinous leaves, (the "prickly pear" of other tropical lands,) we noticed but rarely here and never with either flower or fruit. Amongst the sea-weeds floating close in with the land, we found several examples of the |

Sargasso or gulf-weed, usually noticed in such extensive banks in the Atlantic Ocean. I regretted that we had not an opportunity of examining minutely the weeds growing on the rocks around the Cape, as it was probable that we should have found this species in its rooted state. But the fact of its appearance here in any form is interesting, inasmuch as it proves that this mysterious fucus inhabits the waters of the western, as well as the eastern side of the American continent. |

CHAPTER II.

On the 17th of December we made sail from Cape St. Lucas and steered to the S.E., with |

winds from N.W., and a strong current setting to the eastward. On the afternoon of the 23rd, when we were far distant from any land, a strong sensation was produced amongst our ship's company by the watch at the mast-head reporting the approach of a solitary boat, filled with human beings. On closer investigation, however, the object seen proved to be a log of drift wood, with several boobies perched upon it: the timber, undulating with the waves, and the actions of the birds to preserve their balance, presenting, in the distance, a very deceptive resemblance to a boat, with her crew pulling hard at their oars. On the 17th of January, 1836, we crossed the equator in long. 112° W., and dropped to the westward with the line current. The Cachalots we found here were chiefly small parties of half-grown males, journeying to the eastward. They were so active and shy that our average success amongst them was much less than we had experienced in the previous year. Early in the month of February we shaped a course for the Marquesas group. In lat. 6° S., long. 134° W., the easterly winds began to freshen every night, in the manner of a "land turn;" small white noddies came about the ship; and frequent squalls, with thunder, light- |

ning, and rain, denoted our approach to an insular mountain-land. On the 19th of February, La Dominica and Santa Christina were in sight. We sailed through the narrow channel which separates these two islands, and on the following morning cast anchor in Resolution Bay, Santa Christina. The ship was scarcely moored, before Eutiti, and several other principal chiefs of the island visited us in their canoes; whilst crowds of inferior natives flocked on board, and continued to be our daily visitors. They informed us that seven sail, British and American, had touched at this port since our last visit. We found our missionary friends zealously occupied; but no alteration had taken place in their professional prospects. The natives continued to behave towards them with propriety, and to a certain extent with kindness, but had not as yet manifested any disposition to receive instruction, or to abolish any further their heathen prejudices. A congregation of fifteen or twenty persons, including Eutiti and his family, assembled in the valley of Vaitahu for Christian worship on the Sabbath morning; but their attendance was capricious, and more the result of persuasion, or intended as a compliment to the missionaries, (who addressed them in the Mar- |

quesan tongue,) than from any desire to profit by the good counsel offered to them. Eutiti expressed much anxiety to retain the missionaries in his territory, and was at little pains to conceal the selfish policy that influenced him. He persists in regarding their interests as identical with those of the shipping frequenting the surrounding seas, and in some measure with the British government; from which last he entertains great hopes of receiving a valuable present of cannon and ammunition. The entire island continued to be in a state of profound peace, and since our last visit its tranquillity had been interrupted only on one occasion, when a woman from the weather valley, Mutabu, having hung her cloth upon a sacred edifice at Vaitahu, the people of the latter village armed themselves to avenge the sacrilege by the slaughter of the offending tribe. Their angry feelings were calmed, however, by the remonstrances of the missionaries; and the feud was at length amicably settled, by the inhabitants of Mutabu paying the offended party a number of hogs, as an atonement for the offence of their countrywoman. The only advance these islanders had made in civilized arts was an attempt to distil an ardent spirit from fermented bananas, under the tuition of some Society and Sandwich |

Islanders resident among them. The liquor they produced was but little better than vinegar. Nevertheless, several of the natives had indulged in it, to the extent of intoxication, and had proved riotous and quarrelsome. We observed with regret this growing desire for ardent spirits, since, should it become as great here as at the Society Islands, the disunited form of the government will tend to perpetuate the vice, and foster its most destructive effects. Of the pair of Moscovy-ducks we had left on this island, the drake only remained, his mate having been stolen and eaten by the natives, who had previously taken the same liberty with her eggs. Captain Stavers kindly repaired this loss to the missionaries by presenting them with another duck of the same breed; and at the same time gave some admonitory hints to Eutiti on the propriety of encouraging the propagation of the bird, as a mean of increasing his commerce with shipping – the only topic on which his sensibility could be excited. After remaining five days in Resolution Bay we continued our cruise to the westward and S. of W. until the 11th of March, when we made the Society Islands, and hove to off the harbour of Fare, Huahine. Upon landing at the settlement we were re- |

ceived by a crowd of stout, orderly, and well-attired natives, who, at our request, conducted us to the residence of their worthy missionary, Mr. Barff, from whom we received many polite attentions. This island, (which is the easternmost of the Society group,) is composed of two insular mountain lands, closely approximated to each other. The northern and largest section is called Huahine nue; the southern and smallest, Huahine iti. Both are nearly surrounded by a common barrier-reef; and the tranquil water it encloses is studded with numerous verdant motus. The bay of Fare (Owharre of Cook) is in the N.W. side of Huahine nue. It is protected from the ocean by a barrier coral-reef, which has a broad and deep aperture that permits shipping an easy access to the Bay, unless the trade winds should blow strongly from S.E., when ingress would of course be denied. Notwithstanding some defects in its anchorage, and a natural impediment to ships obtaining a convenient supply of fresh water on its shores, this harbour has been more commonly the resort of South-Seamen than any other of the leeward cluster: supplies of live-stock and vegetables being abundant, and the natives friendly and anxious for traffic. |

The settlement at Fare occupies a tract of level land, of crescentic form, and about two miles in length – its southern extremity bounded by a bluff cliff; its northern, stretching into the sea in the form of a low and extensive tract of sandy soil, picturesquely clothed with dense groves of cocoa-nut trees. The lowlands are well watered and exceedingly fertile: in no other spot of similar extent had I seen so profuse a display of cocoa-nut, orange, and lime trees, as was here exhibited. The dwellings of the residents are scattered far asunder, but respectably built. Convenient paths intersect the land in every direction, and conduct to the adjoining districts; some excellent causeways, constructed of block-coral, shorten the road where creeks or inlets of the sea intervene; and several small rustic bridges facilitate the passage over as many narrow but deep rivers. The Christian church of this settlement is a large and handsome edifice, erected close to the sea-side. The residence of the missionary is situated more remote from the coast. It presents traces of former value, but is at present sufficiently dilapidated and modestly furnished to acquit its apostolic occupant of any overweening attention to his personal comfort. There are, indeed, but few missionaries in Polynesia |

more respected by natives and foreigners than Mr. Barff; and there are also but few, who, from the even tenour of their course in active and useful benevolence, have better deserved that tribute. He has resided for more than twenty years amongst these islands; has been indefatigable in labouring for the cause he advocates; and though himself little prone to display, his patient and intelligent researches have proved a valuable fund to his many more literary colleagues. The population of Huahine amounts to about 2000 persons, of which the greatest proportion resides at Huahine nue, and chiefly at Fare, or the adjacent districts. The supreme authority of the government is vested in the person of the royal chiefess Ariipaea, sister to Tamatoa. king of Raiatea. Oxen, ducks, and pigeons are the most useful exotic animals introduced to this island. Amongst the indigenous fruit-trees, the mountain-plantain (fei) obtains on the elevated lands, but is so scarce that its fruit is eaten only by the chiefs. In the garden attached to the missionary's house at Fare, we noticed a plantation of tall and vigorous coffee-shrubs, at this season covered with a profusion of ripe and scarlet fruit. Mr. Barfff kindly presented |

to us several pounds of their recent berries, which, when prepared for the table, afforded a strong and well-flavoured beverage. It was only at Oahu that we had hitherto seen any attempt to introduce the coffee-plant into Polynesia; though Mr. Barff informed me, that he had planted it on several islands; and, where proper attention had been paid to its culture, the result had been always satisfactory. Near the northern extremity of the settlement I remarked a tall and venerable Shaddock-tree, (Citrus decumana,) loaded with large and ripe fruit. This is the only tree of its kind that exists on any of the Society Islands, and it bears the reputation of having been planted by Captain Cook, when he visited this island to restore Omai, the Society Islander, who, on a former voyage, had accompanied him to England. The spot on which the tree flourishes is a portion of the land obtained for Omai by Captain Cook, and hence named Beritani, or Britain, by the natives. Ever anxious to compare foreign productions with those indigenous to their own soil, the Huahine people name this tree (from a similarity in its fruit and growth) uru papa, or the white man's bread-fruit tree. They do not eat the fruit, but betray a partiality for its odour by wearing fragments of the rind and |

pulp as necklaces. Every effort to propagate this Shaddock-tree by its seed has failed and I am not aware that any other method has been tried. It certainly affords as interesting and authentic a relic of our great navigator as any Polynesian island can produce. Quitting Huahine, we made sail for Raiatea, and, on the 12th of March, brought up at our former anchorage off Utumaoro, The state of this settlement had very materially improved since our last visit. Its inhabitants were more numerous and cheerful, more orderly and better clothed, than we had seen them at any former period. Their dwellings, also, though still dirty, had a somewhat more comfortable and respectable appearance. The royal chief, Tamatoa, whom we had last seen so lost to all sense of propriety, and plunged in degrading debauch, was now an altered man, healthy and robust, correct in his conduct, and. residing in a neat hut, until a wooden house, now building in the best style of architecture in these islands, should be completed for his use. The pleasing improvement a few months had wrought in this community was chiefly to be attributed to a voluntary and rigorous abolition of the use of ardent spirits, as well as to the reestablishment of a missionary authority on the |

island: Mr. Platt having relinquished the cure of Borabora, (where the natives are reported as "too bad,") and fixed his residence at Utumaoro. Mr. Platt was at this time absent on a visit to the Navigator Islands; yet the presence of his family alone, at Raiatea, appeared sufficient to keep the natives in their line of duty. It required as many visits as we had paid to this island to enable us to form any correct estimate of the character of a people so versatile in their conduct. From what I observed, it is evident that they hold any one moral character upon a very frail tenure; and as they are influenced by good or bad example, and controlled by wholesome authority or left to the sway of their passions, they are ever ready to pass rapidly to the extremes of good and bad; and afford at short intervals, and often in the same persons, striking examples of saintly virtues, or of the most degrading vices. A circumstance occurred, during our present visit, which reflected great credit upon the state of the laws at this island. A few hours after our arrival at the port, a knife was missed from one of the boats; and as no natives excepting the pilot and his boat's crew had been on board the ship, suspicion naturally fell upon that |

party; but as the loss was trifling, the fact was casually mentioned to one of the chiefs and we thought no more about it. On the following morning, however, one of the native judges came off to the ship in his canoe, bringing with him the stolen knife and a hog. He informed us, that the thief had been detected in one of the pilot's crew, as had been suspected, and that having been tried by the judges and convicted, he had been sentenced to restore the knife and give a large hog as an atonement for his offence. The local defects in the settlement remained unremedied – swamps were as numerous, and bridges and clear runs of water as scarce as heretofore. Disease also, (and perhaps as a consequence,) had in no degree diminished, and the number and distressing character of the maladies of the people, unpitied and unaided, were truly appalling to humanity. On the 15th of March we made sail for the windward, or Georgian Islands. The winds were at first favourable to our progress, but ultimately returned to the trade quarter and compelled us to beat the greater part of the passage. At noon on the 17th we were detained by a calm, about eight miles due east of Sir Charles |

Saunders' Island, Tabuaemanu, or Maiaoiti, (one of the Georgian cluster, and discovered by Captain Wallis, in 1767;) the islands Eimeo and Tahiti being at the same time visible to us, distant forty or fifty miles to the S.E. When approached from the S.W., and while yet distant, Tabuaemanu appears elevated, circumscribed, and not unlike a distant sail. It is a small, though fertile island, of moderate elevation, and wooded to its topmost heights. Its longest diameter extends in a N.E. and S.W. direction, its each extremity stretching into the ocean as a long and low spit, or promontory, covered with cocoa-nut trees. It was formerly celebrated for the excellence and abundance of its yams. It is now employed as a penal settlement from Tahiti. No European missionary resides on its shores: the pastoral charge of the people being included in the duties of the missionary at Huahine, who pays an occasional visit to this spot to superintend the labours of native teachers. On the 19th of March we approached closely the shores of Eimeo, or Mooréa;* and on * An island situated to the westward of Tahiti, from which last it is separated by a navigable strait, fourteen miles in breadth. It is encircled by a distinct coral reef, is nearly thirty miles in circumference, elevated, pecu- |

the following day cast anchor in the harbour of Taone, Tahiti. The moral improvement, so evident in the Raiateans, we found equally great amongst the Tahitians, – by whom indeed the example had been set. Missionary influence now preponderated in this island; and the laws inculcating temperance, soberness, and chastity, were consequently strictly enforced. The distillation and importation of ardent spirits were prohibited, and intoxication severely punished. It is true that this, like all other legal enactments of the same government, was carried to an oppressive extreme; since every private residence in the settlement was liable to an occasional search by the native authorities, when all the prohibited liquor they contained (above a certain quantity, warranted for medicinal purposes) was seized, and the owner subjected to a pecuniary fine; — the odour of the breath of a native, who had indulged in private, was alone considered evi- liarly wild, mountainous, and rugged in aspect; but exceedingly fertile, and abounding in picturesque scenery. The missionary settlement on its shores is chiefly remarkable for a public school, established for the education of the missionaries' children of both sexes; and also for a stone church, (a rare edifice in these islands,) constructed with the coral blocks of ancient morais. |

dence sufficient to convict him before his judges. Nevertheless, it is unquestionable, that feeble measures, or any indulgence. to individuals, would open a path for evasion, and destroy the effect of what has been, for this people, a very salutary and requisite law. The shores of Tahiti now no longer exhibited the revolting scenes of debauchery that disgraced them during our visit in the year 1834. The practice, so prevalent with Asiatic and other semi-civilized governments, of pandering to the indolence and cupidity of the higher classes by oppressing the inferior and more industrious grades of society, was but too evident here. The farmers complained loudly of the heavy duties the chiefs had imposed upon the sale of their produce, and which compelled them either to increase their price, and hence diminish the demand for their commodities, or to relinquish a just remuneration for their toil. We found upwards of twelve sail, chiefly American South-Seamen, at anchor in Papeete harbour; and during our stay, a schooner, belonging to an English resident here, reached the same port, with a cargo consisting of twentyfour tons of pearl-shell and many valuable pearls, the result of four months fishing amongst the islands of the Dangerous Archipelago. |

Some other small vessels, belonging to this island, were absent on distant voyages – a schooner was on the stocks – a fine brig had been recently added, by purchase, to the merchant-navy of the foreign residents – and, upon the whole, the commercial state of Tahiti offered a fair prospect of improvement. A party of natives of the Palliser Islands* had lately arrived here in three large sailing canoes, bearing a customary present, or tribute, of pearls, mats, and cinnet, for the queen of Tahiti. They resided in temporary huts erected upon the beach at Papeete, where their canoes were drawn up, and presented an interesting gipsy-like group of men, women, and children. In personal appearance they resemble the Tahitians; though their complexion is some shades darker, and their features harsher and less agreeable. Their canoes are superior in size and construction to those in general use amongst the Society Islands, and the paddle with which they are steered has the part corresponding to the blade shaped as a vertical crescent, or tailfin of a fish; from which last, it is more than probable the idea of its form was originally derived. * Situated to the eastward of Tahiti, and now included amongst the Paumotu, or Pearl Islands. |

On the 27th of March I accompanied Mr. S. Henry (the son of the worthy and venerable missionary of that name) to his estate near Mairipéhe,* with the intention of proceeding from thence to visit the celebrated mountain-lake at Vaihiria. From Papeete we journeyed on horseback along the west coast, by a road which was good for a short distance beyond Bunaauia, but which ultimately became rocky, or encumbered by brushwood, and occasionally lost on the sands of the sea-shore. Its winding course, however, unfolding to our view a constant succession of opening valleys, or towering and verdant heights, afforded scenes of extreme beauty; while many of the spots we passed possessed a local interest which the kindness and intelligence of my companion did not permit me to disregard. A short distance beyond Bunaauia, we crossed a plain, memorable, in the history of the civil wars of this island, as having been the scene of the decisive battle, fought in the year 1815, between the idolatrous and Christian Tahitians; when the latter, under the command of Pomare II., drove their adversaries from the field with great slaughter, and the loss of their leader Upu- * A district on the S.E. side of Tahiti, and distant about thirty miles from the settlement at Papeete. |

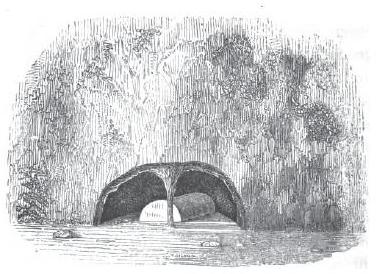

fara, the chief of Papara, and brother to Tati, the present chief of that district. In the vicinity of the battle-field, on a spot named Paea, in the district Teoropaa, there stands, close to the sea, an ancient morai, – a colossal pile of coral blocks, originally of square form, but now ruinous, and almost concealed by the spontaneous vegetation that clothes its surface. On the S.W. side of the island, I noticed, with interest, the numerous caverns which perforate the precipitous cliffs that form this portion of the coast. One of the most remarkable of these, opened at the base of a mural cliff, about two hundred feet in height, and its face covered with ferns and other elegant verdure. The cavern, (which at its mouth formed a very large and perfect arch,) diminished in size as it receded into the cliff; but to what extent it penetrated we could not ascertain, as its floor was occupied by a sheet of fresh water of considerable depth, produced by infiltration through the rocks above. The land intervening between the sea and this capacious cave, rises gradually as an amphitheatre, enlivened by rills of water, and mantled with a profuse vegetation, including some splendid varieties of the fern tribe; and were it cleared from brushwood, would display, together with the verdant cliff and cavern entrance in the back- |

ground, a magnificent view from the lagoon-sea that bathes its shores. But two causes can be assigned for the existence of these mysterious caves; namely, lava-currents, or the inroads of a turbulent sea, previous to the growth of a protecting reef; and of these, the latter appears the more probable cause, since we find on the exposed coast of Matavai Bay some similar caverns, filled with sea-water, and invaded by a heavy surf. We also noticed on this coast many subterranean streams, rising as springs of fresh water from the midst of the sea, at various distances from the shore. Their situation is marked by small eddies, or whirls, on the smooth sea over the coral reef; and upon some of these the natives have placed bamboos, with apertures in their sides, through which the fresh water flows as from a pump. When fishing on the coast, in their canoes, it is not unusual for the natives to dive beneath the surface of the sea and quench their thirst at these fresh-water springs. In the afternoon we entered Papara; a large and fertile district, containing a missionary residence, and a Christian church of vast dimensions. The missionary at this station is Mr. Davies, whose pastoral charge (including the population of Papara and some adjoining dis- |

trict) cannot be estimated at less than two thousand souls. Tati, the governor of this district, is a member of the royal family of Tahiti; and, owing to his rank and possessions, bears considerable sway in the politics of the island. In passing, we paid a visit to this chief at his residence, – a large and very superior wooden building, newly erected, and provided with an unusual quantity of European furniture. He received us cordially, and produced a bottle of wine for our refreshment. He is an elderly man, of tall stature, and very corpulent. His features, which are coarse, heavy, and by no means prepossessing, bear some resemblance to the extant portraits of °Pomare II., to whom he is nearly related. In his youth, Tati had been "educated for the church;" or, in other words, initiated in the mysteries of heathen rites, to qualify him to act as a priest amongst his idolatrous countrymen though, in his maturer years, he has proved himself a warm advocate for the Christian cause, and a tried friend to the European missionaries. A short distance further on our journey, we passed a dense plantation of venerable trees – one of the sacred groves of ancient idolatry – and without deviating greatly from our route, approached the sea-side to visit the celebrated |

"Great Morai of Papara," so ably described and delineated by Captain Cook, when it was in the zenith of its popularity. This morai is not, correctly speaking, in the district of Papara; but on a spot named Mahiatea, in the district of Tevauta. It is now much ruined and diminished in height; and vast quantities of the coral-blocks of which it is composed, are scattered on the surrounding soil, and occasionally carried away by the natives for other and more useful purposes. Nevertheless, what remains of the edifice is strongly expressive of its original gigantic and not unornamental structure; and while it excites our wonder, as a monument of the almost incredible energy a naturally-indolent people can display when stimulated by superstitious zeal, it equally claims our regret that so interesting an antiquity should suffer from other devastations than those of time. Its height, though abridged, is yet above forty feet; the base retains its original size and form, and the summit its pyramidal character; the compartments between the terraces are alternately composed of square, and apparently hewn, blocks of coral, and parallel horizontal rows of globular stones, resembling cannon-balls. Unlike the impressive grove of Tamanu and Casuarina trees that surrounds the great morai |

at Opoa, the ancient thicket around this edifice is chiefly composed of Purau and tangled brushwood, and contains but few of the more funereal trees. In the evening we reached Mr. Henry's residence at Atinua, where the kindest hospitality obliterated the fatigues, and enhanced the pleasures, of the past day. At day-break on the following morning I quitted Atinua, in company with a native guide, and rode four miles further along the coast, to Mairipéhe, whence we proceeded on foot, inland and to the northward, for the lake of Vaihiría. For a short distance, our route lay over an extensive tract of fertile land, in some parts thinly strewn with the cultivated plots and modest huts of the natives, though more generally overrun by a rank vegetation and intersected by streams, which compelled us to take to the water and practise those aquatic exercises which we had afterwards so frequently to repeat. As we advanced inland the country assumed a wilder and more romantic character. An occasional hut, erected as a temporary shelter for the fruit-gatherer, was the only trace of human occupation; and a river of respectable size, arising inland, near Vaihiria, flowed through the land with a winding and impetuous course, to |

empty itself into the sea on the coast of Mairipéhe. The road to the lake follows closely the channel of this river, or only departs from it to evade circuitous bends, rapids, or unfordable depths. In our journey to Vaihiría and back we crossed this stream one hundred and eighteen times. It was often both broad and deep at the fords, and its current so strong as to require some exertion to stem it. The dry and detached paths, trodden by former visitors, were narrow, often concealed by vegetation, and covered with loose and rugged stones that rendered travelling painfully laborious. Midway between the coast and Vaihiria, a solitary cocoa-nut tree, serving as an index to this distance, was the last of its family we passed. The Guava-shrub, also, became more scarce, and gradually disappeared, although it is making vigorous and promising efforts to accompany man to the borders of the lake. The ordinary vegetation of the coast was now exchanged for groves of the mountain-plantain, covering the neighbouring heights with their palmy foliage, crowned with erect clusters of scarlet fruit; elegant arborescent ferns and many varieties of club-mosses clothed the banks of the river; and several continuous acres of land were |

covered solely with thickets of a species of Amomum, called Obuhi by the natives, its pinnated leaves rising to the height of eight feet above the soil, and emitting, when crushed, a powerful and agreeable odour, not unlike that of pimento. The towering heights on either side of our route frequently presented the deceptive appearance of closing upon our path, and as often led me to anticipate the task of ascending them. We continued, however, along the torrent, without surmounting any abrupt eminence, until in the vicinity of the lake, when a steep and rugged hill rose before us, covered with vegetation, and bounded on our left by a lofty cliff, from the summit of which a broad cascade sprung majestically over a verdant precipice, with a fall of more than two hundred feet, and contributed its waters to the river we had tracked. On the summit of this hill, the valley and lake of Vaihiria burst impressively upon our view, spreading at our feet an enchanting scene of placid and picturesque beauty, for which no description had prepared me, since none could do justice to its merits. A short and abrupt descent conducted us into a level valley, bounded on all sides by rocky heights, luxuriantly wooded, and inaccessible, except at the spot where we entered, or over a similar hill on the opposite side. |

The lake occupies one extremity, and a great portion of the valley. It is nearly circular in form, and about one mile in circumference; its surface tranquil, or ruffled but for a moment by the passing breeze; its waters fresh, and of a dull-green colour. Its greatest depth, as ascertained by sounding, does not exceed fourteen fathoms. Two spiry cliffs, conspicuous for their majestic height and uniform appearance, bound the lake on opposite sides, many small and silvery waterfalls pouring from their crests, and stealing silently over the short and bright verdure of their precipitous faces into the basin beneath. Its shores are formed in part by the bases of these cliffs; but chiefly by a beach of soft black sand, strewn with cellular boulders, and by low ledges of breccia, or volcanic rock of a very friable character. Some black and rugged rocks, also, rear their heads above the smooth surface of the lake, presenting a gloomy but powerful contrast to the mild and reposing character of the surrounding landscape. An extensive plain, stretching from the border of the lake to the foot of the more remote hills, is almost entirely covered with a species of Polygonum, very closely resembling the land variety of P. amphibium. Eels are the only fish known to inhabit the lake, and the privilege of |

capturing them is the hereditary right of a native family residing at Mairipéhe. A flight of wild-ducks rose from the water on our approach; and the plaintive note of a bird, not unlike the cooing of a dove, was the only sound that interrupted the death-like tranquillity of this secluded spot. A few rafts, made with the stalks of the mountain-plantain, lying on the borders of the lake, and some temporary huts, covered with the leaves of the same tree, betrayed that other visiters than ourselves had recently intruded upon this scene. They might, probably, have been a native party which, a few weeks before, had escorted the queen, Aimata, on her first visit to Vaihiria; or the officers of H.B.M.S. Challenger, 28, who had made an excursion to this spot in the previous year. The Tahitians, ever fond of the marvellous, assert that the waters of the lake are unfathomable; but a circumstance which occurred to the Challenger's party, and which was related to me by Mr. Henry, proves, how much easier it is to find the bottom of the lake than to fathom the duplicity of the Tahitian character. One of the officers, when crossing the lake on a raft, for the purpose of shooting wild-ducks, found his frail craft in danger of upsetting, and, in order to save him- |

self, allowed a valuable double-barreled fowling piece to fall from his hands into the depths below. A native attendant was set to dive for the lost property, which he did, and declared it was not to be found; and it was not until he had been urged to repeated attempts by Mr. Henry, that he at length produced it. This man afterwards confessed, that he had found the gun when he first dived, and had concealed it in a spot, under water, where he could readily obtain it for himself, at another and more favourable opportunity; and that he had no intention whatever of restoring it to the rightful owner, if Mr. Henry had not been so angry and peremptory on the subject. The geological character of the surrounding land strengthens the opinion that this lake is the crater of an extinct volcano, filled with water by cascades and rivulets, as well as by subterranean streams, that open perceptibly on many parts of its surface. That there may be some exit for its waters is probable, though at present destitute of proof. The height of the spot it occupies is estimated, by Captain Beechey, at 1,500 feet above the level of the sea. The ascent from the coast, however, is made by a circuitous route, and is so gradual as to be almost imperceptible: the direct dis- |

tance from Mairipéhe to the lake does not exceed eight miles. It was noon when we reached Vaihiría. The sky was clouded, the temperature low, and every thing around us saturated with moisture. The morning dew on the thickets, the river-fords, and subsequently, some heavy showers of rain, had wetted us thoroughly; but this was only a temporary inconvenience to my native companion, who, on starting, had taken the precaution to roll his body-cloth into a small and compact form, and now invested himself in its dry folds, with something, I thought, like satirical satisfaction. But I had my revenge; for the dampness of the spot defied all his efforts to produce fire by rubbing two pieces of wood together, in the usual Polynesian manner, and enabled me to display the superiority of civilized over savage expedients, by immediately producing the desired element with a Lucifer-match. Returning by the same route, we reached Mairipéhe* by six o'clock in the evening. This district includes a wide extent of fertile plain, * A name compounded of two Tahitian words, signifying "to finish a song;" the minstrels, who formerly strolled round the island, having been in the habit of commencing their performances at Papara, and finishing them at this place. |

and its population presents a healthy rustic appearance, which we look for in vain amongst the dissipated natives of the more commercial ports. Its coast is well protected by the barrier coral reef; and the tranquil water within the latter, affords good anchorage for shipping, off a native village where every essential supply can be obtained. Previous to my return to Papeete, on the morning of the 29th, I devoted a few leisure hours to viewing the beauties of Atinua. The principal building on this spot is Mr. Henry's residence, a neat and convenient dwelling, erected at the foot of some pastured hills, and surrounded by cultivated lands, which include the largest sugar plantation on the island. Native huts, grouped around, were mingled with superior habitations occupied by foreigners, (English and Americans,) pursuing employments as respectable mechanics. The refreshing coolness of the morning air, passing through a dense foliage; the appearance of cattle, swine, and poultry, strolling about, orderly and domesticated; together with the general aspect of rural comfort this estate presented, would have induced me to fancy myself in a respectable English farm, had not the plumy cocoa-nut palms and broad-leaved bananas destroyed the illusion. |

CHAPTER III.

On the morning of the 31st of March, we took advantage of the land breeze to sail from Tahiti, on a cruise to the northward. On the following day we passed close to Tetuaroa, a low and extensive coral-island, belonging to the crown of Tahiti, and much frequented by the Tahitians for purposes of health or pleasure. Its structure is analogous to that of Caroline Island, which I have already described. On the 4th of April we again visited Maurua, for the purpose of renewing our stock of yams; |

and in the following evening sailed from that island, with winds from N.W. and very boisterous weather. The same contrary winds opposed our progress to the northward for several days; and we had not proceeded beyond the sixteenth degree of south latitude, when it was discovered that a leak in the bow of the ship, two feet below water-mark, * and which had for some time required a frequent use of the pumps, was now so much increased as to require our immediate return to Tahiti for its repair. We consequently tacked to the S.E., and the wind being favourable to our reversed course, reached Tahiti on Saturday, the 22d of April, and cast anchor in the tranquil harbour of Papeete Bay. The day of our arrival being the Sabbath at this island, I landed in time to attend divine service at Papeete Church, where Mr. G. Pritchard, the indefatigable missionary of this district, officiated to a large congregation of natives, including the queen, Aimata, and her husband. The conduct of the two latter personages was not, on this occasion, calculated to set a good example to their subjects. The queen was * The precise situation of this leak was detected by the use of a long bamboo, applied in the manner, and on the principles, of the stethescope. |

playful and inattentive; and her husband did not even enter the church, but, seated on the threshold, amused himself during the time of service with cutting sticks, playing with children, or in the enjoyment of passing events in the road without – pastimes for which he was occasionally rebuked by an elderly chief who stood near him. It was pleasing, however, to notice the manner in which this day was preserved by the mass of the population. No canoes were to be seen on the water, nor any natives occupied with traffic or manual labour; their food, procured and cooked on the previous day, is of better quality and more abundant than ordinary; the floors of their huts are usually strewn with a fresh layer of grass; and natives of every grade, attired in their best apparel, may be seen hastening to church at the sound of the summoning bell, and returning an orderly, if not an edified, train. To the stranger, these public demonstrations of piety convey an opinion highly flattering to the native character, and lead him to infer, that if the Tahitians do not possess a true religious sentiment, they at least contrive to ape that virtue exceedingly well, and deserve to be praised for their docile obedience to the wholesome laws enacted for them. |

I availed myself of our return to this island, to visit the Ofai marama (moon-stone) of the natives; a natural curiosity, second only to the lake of Vaihiria. It is situated on a spot named Puna-ru, about two miles and a half inland from the west coast. The road to it, as pursued by my native guide, penetrated the country immediately behind the village of Bunaauia, and traversed a valley, covered with luxuriant herbage, and enlivened by a broad stream, winding through its centre; whilst oxen and horses, grazing on the rich pasturage, and occasional groupes of native huts, helped to form a very pretty rural landscape. At the head of this valley, in a narrow rocky defile, bounded on either side by precipices, we found the object of our curiosity – a prostrate basaltic column, half-imbedded in the soil, and lying in a cave, excavated as it were for its reception, at the base of a mural cliff of considerable height. Its position is horizontal, and nearly parallel to the sides of the cave; its length about seven feet, its height three and a half, and its breadth nearly six feet; its surface is dark and polished, and marked with a few vertical fissures, so regularly disposed as to convey an impression that the column is composed of several blocks, united by human ingenuity. It is connected in |

some parts with the rock of the cliff, and its extremity, that presents at the mouth of the cave, has a smooth surface, resembling the half-risen moon in shape, whence its native name. It offers, on the whole, an interesting example of a basaltic column, which originally formed a portion of the surrounding cliff; but whose more compact structure has retained its integrity, while the rock around has separated in slaty exfoliations.

The British man-of-war brig Zebra, which now lay at anchor in Papeete harbour, was the only ship-of-war we met with during the voyage. Her trim and well-disciplined appearance recalled many agreeable thoughts |

of our native land, and from her commander and officers we received many polite and valuable attentions. The presence of a man-of-war in their port, seemed to produce any thing but a joyous effect on the natives; since they derive but little amusement or profit from a ship of this character, and the rigour of her discipline is not at all adapted to their taste. There was at this time, however, an unusual degree of bustle and activity amongst the natives on the coast, the greater number being employed in gathering bark for the manufacture of native cloth; while, in a large shed at Papeete, more than fifty young females, their heads bedecked with flowers, assembled daily to make the welkin ring with the sound of their cloth mallets. They all told me that they were working for the queen; and I imagined they were preparing some customary tribute, until I was informed by the European residents, that such display invariably attends the presence of a foreign ship-of-war in the port, and is intended to impress the naval officers with a favourable opinion of native industry. Previous to taking leave of this island, which must be deemed the head-quarters of British |

missionaries in Polynesia, I may with propriety hazard a few remarks upon the apparent extent and effects of missionary exertions; although, from the conflicting opinions existing on this topic, the task becomes one of extreme delicacy. I have been led by personal observation to believe, that while the missionaries at these islands have been libelled by one party, they have been too highly lauded by another; and that the strictures of Kotzebue are not more unworthy of implicit belief than the flowery and exaggerated tone of description adopted by the missionary party. From the statement of the one, we should judge that missionaries were tyrannical, ignorant, bigotted, avaricious, and almost the cause of every vice perceptible in the native character, and that the natives themselves are in a more degraded state than at the period of their most barbarous idolatry. From the other, we are to believe, that the missionaries are universally beloved; that the natives are saints, martyrs, and primitive apostles; that their churches are cathedrals, and their grouped huts cities. But with whichsoever of these party impressions the voyager visits the debatable land, he will find himself disappointed; and by observing calmly and unprejudiced, will doubt- |

less determine, that the truth rests in the medium. It cannot be denied, that from the landing of the first party of British missionaries, in 1797, to the present time, a constant tendency to a fixed point of improvement has been evident in the more favoured Polynesian nations. – I say a fixed point, because I believe, that after idolatry has been supplanted by the Christian religion, and the elements of education introduced, the work will remain stationary for a time; and that a nobler superstructure can only be raised by the maturing influence of many years' intercourse with civilized nations. The first steps have been successfully attained by the missionaries, at both the Society and Sandwich groups, after many years of anxious toil and dangerous re-action; and their chief duty at present consists in retaining the ground they have gained, and in giving such intellectual improvement to the rising generation of natives as circumstances may permit. And it will be noticed, in the accounts I have given of distinct islands, how soon the absence, or loss of influence, on the part of their missionary instructors, causes the capricious natives to revert to their former excesses, and indifference to |

moral laws. A missionary, resident amongst these newly-converted people, has almost a regal influence; for however passive he may be, his presence alone has the effect of stimulating the chiefs and church party to enforce the observance of religious law amongst the people; whilst the latter, from a feeling of decorum, and a love of approbation, (peculiar to their character,) act with much show of propriety; since no native, however depraved in principle, will act in open violation of morality under the eye of his missionary, whom he always regards with a kind of innate respect, although professing, to his party, that he holds both the man and his precepts in contempt. It may be asked, how far has commercial intercourse alone, with civilized nations, tended to the improvement of these islanders? I would answer, that the effect of commercial intercourse can extend but little farther than to make the natives acquainted with civilized habits, (and bad habits they too frequently are,) and by the introduction of foreign manufactures, to increase their comforts, and afford them the means of imitation. But it would be absurd to assume, that the transient visits of shipping, or even the residence amongst them of foreign merchants, |

with minds engrossed by mercantile speculations, and destitute of all responsibility, would go far to correct or educate these people. The press, also, (that mighty engine for the development of the human intellect,) as well as the reduction of the Polynesian languages to a standard rule, would have long remained absent from these nations, had their introduction depended solely upon commercial relations with their protecting countries. Since some few errors and abuses are inseparable from human nature, we may admit that the missionaries perform their duties with great moderation and purity. The principal faults laid to their charge, are too great an interference in the political and domestic affairs of the natives, and too keen a participation in commercial transactions. Nor are these charges altogether groundless; although more frequently applicable to individuals than to the collective body. The missionaries shield themselves from the blame of political interference, by attributing all legal enactments, at their stations, to the will of the principal natives; but the influence they exercise over the minds of the chiefs, and the frequency with which the latter consult them upon all important affairs, are too well known, |

to permit the administration of the one party to be unassociated with the wish of the other. Commercial dealings, although irrelevant, may not, perhaps, be deemed strictly opposed to their spiritual profession, unless permitted to interfere with the due performance of their pastoral duties; and, when conducted in a liberal and upright manner, may afford useful instruction to the natives; but it is not considered just, that, as salaried officers for the performance of a distinct duty, they should present themselves as competitors with the increasing number of merchants, resident on the islands, and dependent for their support solely upon their commercial success; and hence embroilments ensue, which should with propriety be avoided. If shipping experience any inconvenience from missionary supremacy in these islands, it is in some measure repaid to them, by the comparative security with which they may approach the shores of a land where they see the dwelling of the missionary erected as a beacon of peace; and this the more especially, as the missionary is usually the first to quit the spot, when the natives are insensible to control, or involved in the turmoil of war. On the whole, we have much reason to be satisfied with the conduct of |

our Polynesian missionaries, and to admit that they have done all in their power to improve the natives, and to implant in their minds respect and esteem for the British character. Leaving Tahiti on the 2nd of May, on our return to England by the way of the Cape of Good Hope, we steered to the N.W., until near the equator, in long. 166° W.; and then shaped a westerly course between the parallels of 2° and 3° S. lat,, with winds chiefly from N.E., and a current setting to the westward at the rate of one mile an hour. Crossing the meridian of 180°, on the 22nd of May, we commenced reckoning east longitude, and noted the following day as the 24th of the month, (thus reducing our current week to six days,) in order to reconcile our time with the apparent loss we should sustain of twenty-four hours, upon our return to the meridian of Greenwich by this, the western circuit of the globe. May 26, 1836. – In lat. 2° 30' S., long. 175° 10' E., discovered a low and extensive island, covered with trees, and surrounded by a sandy beach, with moderate surf; some smoke seen rising from the land, led us to believe that it was inhabited. Allowing for a difference of one degree in longitude, this would appear to be |

Rotch Island, discovered by Capt. Clerk, of the John Palmer, in 1826, and laid down by Krusenstern, in lat. 2° 30' S., long. 176° 10' E. A current, setting strongly to the N.W., caused us to pass its shores with a rapidity, by no means consistent with the light airs, approaching to a calm, which prevailed at the time. In lat. 2° 53'S., long. 174°'55' E., a remarkable white line was observed on the surface of the ocean, about two miles a-head of the ship, and bearing the appearance of a low surf, breaking on a sand-bank, or reef. The ship's course was altered, until a boat, lowered to ascertain the true character of the water, displayed a signal that no danger was to be apprehended, when we resumed our course, and soon after passed through the object of alarm. It proved to be an undulated line of froth, or scum, several yards in width, extending on either side as far as was visible with the naked eye, and accompanied by a heterogeneous assemblage of floating mollusks, small fish, crabs, and other marine animals, drift-wood, and oceanic birds. The birds formed the most mysterious feature of the phenomenon: they were chiefly of the noddy and petrel families; and whilst some of them appeared but recently dead, others lay in a torpid and helpless state on the surface |

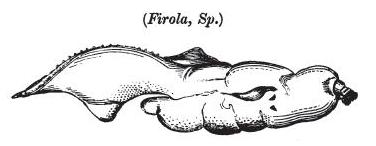

of the sea. A black petrel, (Procellaria fuliginosa,) in this latter condition, was taken by our boat's crew and brought to the ship. It was sufficiently lively when on board; and the state in which it was found could scarcely be attributed to repletion, for, on dissection, I found its stomach perfectly empty. Janthinae, or sea-snails, were the most abundant of the floating mollusks. Their number was immense; and their floats contributed greatly to the white appearance of the froth-line. One species of this family, which I obtained here, was new to me; and is certainly very rare: its shell was yellow; rather smaller and more elongated than J. communis; and the whirl more prominent and spiral. The contained animal was also of a yellow colour; but in the form of its float, and other respects, it closely resembled the ordinary blue-shelled species. This line of miscellanies on the ocean, denoted the termination of a current,* which, in its * Immediately after passing this spot, we lost the strong N.W. current that had hitherto accompanied us; and it is worthy of remark, as associated with the limits of currents, (which are often capricious,) that some of our older navigators have recorded the existence of a current-ripple, and others that of a froth, in nearly this precise place. |

progress, had swept the surrounding waters of their passive, or feeble denizens, and had borne them thus far in a dense and confused mass. Rising and falling with the swell, and its white hue conspicuous above the blue surface of a calm sea, it had much the appearance of surf, and if it had been seen only in the distance by a passing ship, might have added a "suspected shoal" to our charts. On the same day we noticed many kinds of cetaceans, including a school of Sperm Whales, which our boats pursued with success. As we sailed to the westward, also, in the parallel of 3° S. lat., Cachalots were frequently observed; and the produce of several was added to our cargo. They were for the most part shy and mischievous, and were seldom destroyed without some injury to the boats. From a school, attacked by our boats in long. 158° E., four whales were obtained; three of these were adult females, whilst the fourth, a male calf, the offspring of one of the former, did not exceed sixteen feet in length, and produced but three barrels of oil. June 13. – Tench's Island bore S.W., distant seven miles. This is a low and small island, (not exceeding three miles in circumference,) margined by a sandy beach, well wooded, and indeed |

chiefly conspicuous from its tall trees, rising as it were from the surface of the sea. It is situated in lat. 1 ° 39' S., long. 151° 31' E., and was discovered in 1790, by Lieut. Ball, who states that it is inhabited by a stout and healthy race of people. On the evening of the same day, (Tench's Island being still visible,) Kerue's Island, and Mathias, or Prince William Henry's, Island, were seen in the N.W. The latter, which is the westernmost of the two islands, is large, elevated, and covered with verdure; its western extremity terminating as a long, low, and well-wooded point. The three islands last mentioned, appear to have been laid down with extreme accuracy by Lieut. Ball. On the 16th, we saw the Anchorite Islands, bearing S.W., distant fifteen miles; and found in their vicinity a current, setting to the S.W. During a calm, in lat. 0° 56' S., long. 140° E., several logs of drift-wood were seen floating within a short distance of the ship. We went in a boat to the largest, and found it an entire tree, more than sixty feet in length, covered with weeds, barnacles, Unicae, and crabs, and much perforated by the ship-borer (Teredo navalis.) In the water around was assembled a vast number of fish, chiefly yellow-tails, (Elaga- |

tis,) rudder-fish, (Caranx antilliarum,) filefish, (Balistes,) some albacore, brown sharks, and many other kinds, of grotesque forms and gaudy hues, for which even the sailors had no names; the whole presenting a marine spectacle of a highly novel and animated character. The timber was towed to the ship, and a part of it taken on board for fire-wood, and upon making sail, a large proportion of the fish accompanied the ship, and continued to do so for several weeks. After crossing the equator in long. 137° E.,* we renewed a course to the westward, within the parallel of 1° N. lat., and nearly in Bougainville's track of 1768. On the 27th of June, the elevated land of New Guinea was in sight; and on the following day we entered a strait, twenty-four miles in breadth, bounded on the one side by the mountainous island of Wageeoo, and on the opposite, by the Yoel group – a cluster of small islands, the greater number but little raised above the level of the sea, and richly vegetated. One of * On the evening of the day we crossed the line, a frigate-bird alighted on the spanker-gaff, and permitted itself to be captured by hand – an occurrence so unusual at sea, as to be almost unprecedented. |