|

Frederick Debell Bennett 1806-1859 Notes |

|

LONDON:

J. B. NICHOLS AND SON, 25, PARLIAMENT STREET. |

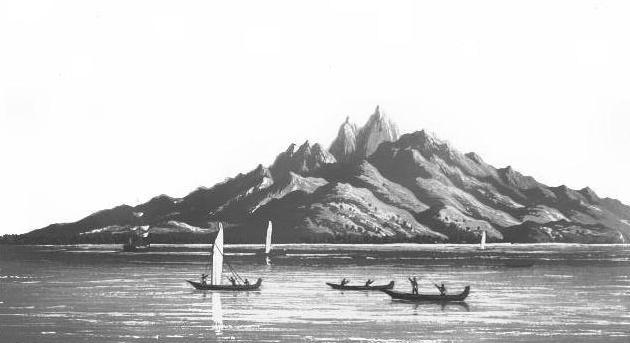

TahitiNorth-West Coast |

actuate his countrymen to depute many of their number to reside with this people of a new world, and pave the way for raising them to the rank of civilized nations. The gleanings I have brought from Polynesia may not, therefore, be unacceptable, although many more able labourers have been busy on the same field. Changes are yearly occurring in that region of the globe, which cannot but prove interesting to the philanthropist; and Nature has endowed those islands with gifts which will long demand our closest scrutiny. Should the appended description of the Sperm Whale Fishery appear too minute, the apology I must offer for it is, that while I wished to make that description thorough, I have felt that some such tribute is due to the Whaler, that he might appear to the world in his true position. By the uninitiated, he is too often regarded as ignorant, and of a degraded caste; whereas, in fact, his occupation is one of extreme anxiety and trial, requires considerable talent and energy for its proper performance, and is, without exception, the noblest branch of our merchant-navy; since, in the absence of war, it is the best adapted to display the courage, perseverance, and enterprising spirit of British sea- |

men, in their truest and brightest colours. The national importance of the service, in a commercial point of view, none can be bold enough to question. The collection of objects in Natural History brought to this country by the Tuscan, consisted of 743 dried specimens of plants, illustrating the vegetation of the lands visited, and 233 preparations of animals, most of which are rare, and many of them unique. The principal part of the botanical collection is now in the possession of A. B. Lambert, Esq. and Professor Don. The zoological I have deposited in the Hunterian Museum of the Royal College of Surgeons in London. To Captain Stavers and the officers of the Tuscan, I feel a pleasure in acknowledging deep obligations for their extreme kindness towards me during the ordeal of so long a voyage, as well as for their voluntary, valuable, and indispensable aid in furthering my inquiries. F. D. BENNETT.

KENT ROAD. April 14, 1840. |

CONTENTS OF VOL. I.

| |||||||

| |||||||||||||

| |||||||||||

| ||||||||||

| ||||||||||||

| |||||||||

| |||||||

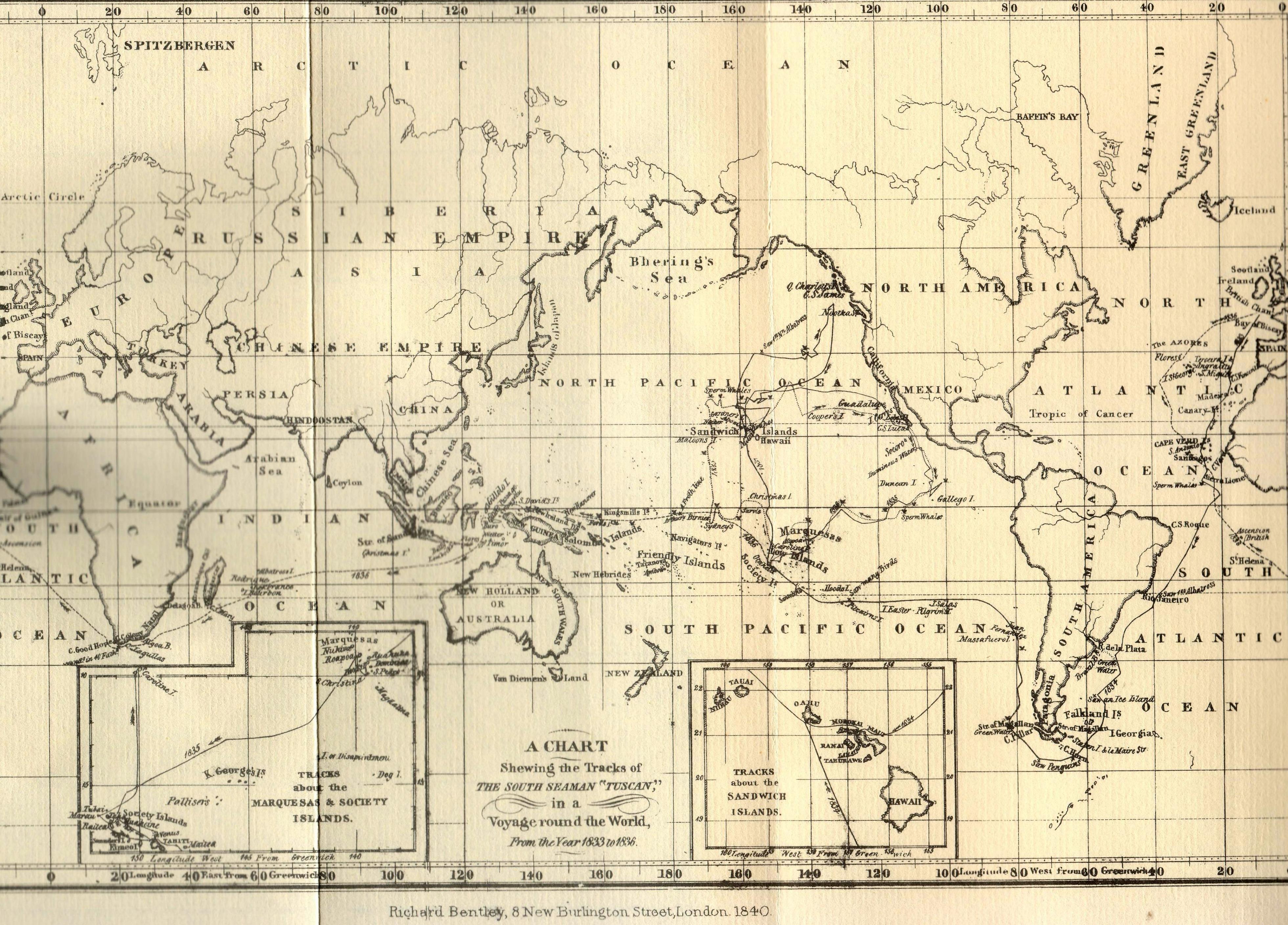

A CHARTShewing the Tracks of

[Click to enlarge image]

|

NARRATIVEOFA WHALING VOYAGEROUND THE GLOBE.CHAPTER I.

October 17, 1833. The ship Tuscan, of 300 tons burden, T. R. Stavers, commander, (in which I was embarked,) sailed from the port of London on a whaling expedition to the Pacific Ocean. It is not very usual for ships engaged in |

this service to take charge of passengers; but, on the present occasion, our party was agreeably increased by three ministers of the London Missionary Society, Messrs. Loxton., Rodgerson, and Stolworthy, who, together with the wives of the two first-named gentlemen, were destined for the islands of the Marquesa and Society groups. Adverse winds, occasioning a detention of six days at Portsmouth, did not permit us to clear the British Channel until the 29th, when we launched into blue water,* and continued an undeviating course to the southward and westward. * Few Englishmen, who have not extended their nautical excursions to more than a hundred miles beyond the mouth of the British Channel, can form any correct idea of the appearance the sea presents throughout the greatest portion of the globe; or how little applicable is the term "sea-green," when the shallow and troubled waters of our own coasts are exchanged for the clear and deep-blue bosom of fathomless oceans. In the latter, the vast expanse of fluid presents one uninterrupted field of a lapis lazuli tint; (the ultra-marine of painters;) and its lifting waves, crested with foam, bear a close resemblance to robes of the richest purple, edged with swansdown or fine lace. This intense blueness of the ocean has been ascribed to the salts of iodine contained in sea-water; but it is more probable that the blue of our atmosphere, or sky, and that of the deep sea, have both the same origin; namely, the clearness and vast accumulation of their respective elements. |

A few hours after we had lost sight of the British coast, a flock of goldfinches, (Fringella carduelis,) driven off the land by some previous heavy gales, took refuge on the ship, and continued with us for two or three days. As every unusual appearance must have its meaning, this was regarded as a good omen by our crew. At noon on the 6th of November, the mountain land of Madeira bore from us S. S. E., distant twelve miles. We passed sufficiently close to its coast to observe the general aspect of the country, its houses, and cultivated lands; but at the same time incurred the penalty of a calm, which delayed us until the following morning. While thus detained, we noticed the phenomenon named by nautical men a "wind-gall," (query, "wind-gale?") or "sun-dog;" – a broad and perpendicular streak of iridescent colours, placed opposite the sun, and extending from a dark cloud to the verge of the horizon. It may be considered to be a fragment of a rainbow; though its colours are much less delicate and diversified than those of the ordinary meteor of that name, and chiefly consist of a lurid-red, or copper-colour, and a bright olive-green, dividing |

the column vertically and in nearly equal proportions. Sailors consider its appearance a precursor of foul weather; nor had we, in this instance, any reason to doubt the correctness of their conclusion; since the succeeding night brought a heavy gale of wind, attended with thunder, lightning, and torrents of rain; and the presence of an ignis fatuus* on the summit of each mast-head, gleaming with its peculiar sickly and supernatural light. Upon entering the northern tropic, the monotony of a voyage across the Atlantic was somewhat relieved by the appearance of a school of small whales, or Blackfish, (Phocaena Sp.,) spouting and gamboling on the surface of the * These mysterious meteors, so frequently observed during a thunder-storm at sea, have invariably a globular form, are about the size of a tennis-ball, and emit a pale blue light. They occasionally appear to pass rapidly from one part of the ship to another, or to drop from the mast-head to the yards beneath, remaining stationary on each for a few moments. Many names have been given to them. When one only is visible it is called Corpo Santo, or St. Helena; when two, Castor and Pollux; and more, Tyndaridh, or St. Elmo's fire. It is probable that their origin is to be found in the effects of evaporation; for, however much the atmosphere may have been surcharged with electricity, during tempests at sea, I have never observed them but as attendants upon rain. |

sea. They were very numerous, and easily approached by the boats lowered in pursuit of them. Three were harpooned. One, however, escaped by the harpoon drawing; the second sunk immediately after death; but the third, which was secured without misadventure, was brought to the ship and taken upon deck entire. It measured sixteen feet in length; and produced about thirty gallons of oil for the use of the ship's company. On the 14th of November we felt the first influence of the N. E. trade-wind, in lat. 21° N.; and at noon on the 16th came in sight of the island of St. Antonio, of the Cape de Verd group, passing it to the eastward, at the distance of twenty-six miles. In lat. 9° N., long. 23° W., (where the accession of calms and light airs denoted that we had exceeded the limits of the N. E. trade-wind,) a school of sperm whales was first observed, and announced by the usual exclamations. A strong excitement instantly pervaded the entire crew; an animating scene of bustle and activity ensued;* and in a few minutes the boats were low- * On these occasions, something like the following expressions are heard from the look-out at the mast-head and the commander and others on deck. There she spouts! – There she blow-o-os! – Where away? – Two points on |

ered and spread over the ocean in pursuit of their prey, leaving the ship almost tenantless and deserted. The whales had been alarmed at the approach of the ship, and proved particularly watchful and timid. One individual, however, was approached by a boat as it lay motionless on the water, in the act of listening, and before it could take the alarm received two harpoons in its body, and was subsequently despatched by the lance in little more than ten minutes. The dead cachalot (which was a female of adult size) was brought to the ship, when the operation of "cutting in" was immediately commenced, and completed in three hours. To obtain oil at so early a period of the voyage greatly exhilirated the spirits of the crew, and naturally led them to anticipate a short and prosperous voyage. Nor had our the lee-bow, sir, a school of whales. – Bring up the glass, boy. – Aye, aye, sir. – How far off do you see them? – About four miles, sir. – Back the main-yard; brail up the trysail. – There she blow-o-s! – Th-e-r-e again! – Flukes! – (An expectant pause ensues, and all are intent to discover the next rising.) – There she breaches! – There she blow-o-s! – Th-e-r-e a-gain! – on the lee-quarter. – Get your boats ready for lowering. – Th-e-r-e a-gain! – Lower away! I see there is a large whale amongst them that wants a passage to London. |

missionary passengers any reason to be otherwise than pleased with the result, since it relieved them from the suspicion of being "unlucky people;" an odium a sailor is always inclined to attach to religious professors, of whatever persuasion. A continuance of calms or light and variable airs detained us a few degrees north of the equator for ten days, during which the weather was oppressively sultry, and rain of very frequent occurrence. Of all the minor inconveniences attending a journey by sea, a protracted calm is certainly the most annoying both to sailors and landsmen. Whatever length of time a passage may occupy, if the motion of the ship is rapid, it is endured with patience whilst, on the other hand, but a few successive days of perfect calm appear as a tedious century, and destroy the equanimity of the most resigned voyager. On those who have not the inclination to resort to intellectual pursuits to beguile their time, the affliction falls with greater force. With them the ship becomes at once a floating illustration of the Castle of Indolence, where "Labour only was to pass the time; This usually indolent period, however, was not entirely so with our small community. The |

boats were frequently lowered to exercise their respective crews; and the decks daily exhibited the busy occupations of many artisans. The sea, also, at this time, presented a very animated appearance, owing to the currents which prevailed thus near the line, as well as to the calm that lay on the surface of the deep and rendered all natural marine objects more distinctly visible. Sharks, attracted probably by the late effusion of blood, were numerous around us; and many examples of the albacore or tunny, (Scomber Thynnus,) and dorado, or " dolphin " of sailors, (Coryphcena hippuris,) were taken by hook and line, or by the barbed spikes of the "granes." The changes of hue displayed by the dying "dolphin" are peculiar; but have been much exaggerated by the poetical descriptions of travellers. Soon after the fish has been removed from the water, the bright yellow with rich blue spots, which constitutes the normal colour of the animal, is exchanged for a brilliant silver, which, a short time after death, passes into a dull-gray, or lead-colour. The original golden hue occasionally revives in a partial manner, and appears above the silver field, producing a very interesting play of colours; but the diversity of tints is not greater than I have described. |

When off the east coast of Brazil, in lat. 22° S., long. 35° W., we experienced a gale from the N. W., which had the effect of bringing about the ship many land birds and lepidopterous insects. Among those we captured was a small heron, (Ardeola, or "paddy-bird" of Bengal,) with cinnamon-coloured plumage; and a large moth, the Hydaspus Jatrophae of Fabricius. December 24. – In lat. 38° S., long. 51° W., a party of sperm whales was seen from the mast head, and the boats lowered in pursuit. One of the school, moving slowly through the water, and conspicuous for his large size, was selected as the object of attack, and successfully harpooned. The creature plunged violently upon being pierced with the weapon, and, setting off swiftly with the attached boat, was not destroyed until after a conflict of nearly five hours' duration. The barometer having fallen in twenty-four hours from 30.10 to 29.60, and other indications of an approaching storm being observed, some anxiety was felt to preserve the valuable prize that had been obtained with so much labour. The body of the cachalot was disposed of the same evening; but the approach of night did not permit the same care to be taken of the head, which was, consequently, left floating |

astern, secured by a strong hawser to the capstan. The night brought a furious gale from the S. W., with a sea running so high that it became necessary to cast off the head of the whale, both to ease the ship, and to avoid the danger which might result from the waves setting such a weighty mass against her stern. On the 26th the wind moderated; but the sea remained turbulent, and presented the green hue of soundings, marking the extent to which the "Brazil bank" stretches forth in an easterly direction from the American continent. The temperature of this tract of discoloured water was much higher than that of the surrounding atmosphere; and communicated to the hands immersed in it a very agreeable sensation of warmth. Many ocean birds of the high south latitudes were now visible around us, as nellies (Procellaria gigantea); blue-petrels, or sperm-birds (Prion pachyptila); pintados, or cape-pigeons; and pios, or cape-hens (Diomedia fuliginosa); with several other species of the albatross family. Among the number of these birds we captured by hook and line, baited with fat meat, was a kind of petrel, which has not been de- |

scribed by our ornithologists. In size* and blackness of plumage, beak, and legs, it bears a close resemblance to the sooty-petrel (Procellaria fuliginosa); but it is distinguished from that species by white bands encircling the head and throat in the form of a bridle. The wandering albatross (Diomedia exulans), often appeared to us in the very gray garment that characterises the young bird; while most of the adult specimens we obtained displayed a vertical line of delicate rose-coloured plumage on each side of the neck; a peculiarity which I had never observed in the many examples of this bird I had in former voyages procured off the Cape of Good Hope. We witnessed an amusing instance of the voracity of this species. A slip of porpoise blubber, that could not have weighed less than three or four pounds, had been thrown overboard and was floating on the sea, when it was pounced upon by a large albatross, and although, as we watched the result, it appeared impossible that the bird could manage such a bulky morsel, with a few moments' strenuous exertion he contrived to swallow it entire. Although * Length twenty-three inches; expanse of wing four feet seven inches. |

unable to rise from the water after the undertaking, he continued to swim pertinaciously in pursuit of a hook and line, baited with the same tempting food, and only escaped being captured by the hook breaking in his beak. Stormy-petrels were frequently about the ship, skimming over the waves in their peculiar rapid flitting manner; every moment dipping to the sea and raising a slight splash on its surface, then rebounding to renew their mazy flight through the air. There is something very interesting in these little birds – they appear too diminutive and feeble to brave the vicissitudes of the open ocean, and yet are always so active and merry on the wing, both in rough weather and in calm; they are, however, more inclined to take shelter from a very severe tempest than other sea-fowl, and are as commonly met with on the equator as in the cold climates of high north and south latitudes. The opinion that their appearance is indicative of a storm is not correct; and has probably arisen from the circumstance of their occasionally approaching a ship for shelter during the violence of a gale. Sailors seldom injure the stormy-petrel. It is true they have not often an opportunity afforded them of doing so; for these birds are not easily shot at sea, and it is yet more difficult to entrap |

them. I have met with a veteran tar who once in his life had killed a "Mother Carey's chicken," as it fluttered for refuge from the tempest under the lee of his vessel, and he always spoke of the event with unaffected contrition. Large shoals of that rare dolphin, Delphinus Peronii, were seen sporting in the ocean as we advanced to the southward. It is a species peculiar to this region; and differs essentially from the common dolphin in being coloured black and white in nearly equal proportions, and in being totally destitute of any appendage, or fin, on the back: from this last peculiarity it is named by seamen the "right whale porpoise." On the 4th of January, 1834, the ship passed within six miles of an iceberg floating on the sea, in lat. 47° S., long. 57 1/2° W. It was of square form, and had a small conical hummock attached to its base. The summit was level; but in some points of view the effects of refraction caused it to appear as an inclined plane. It had a dazzling whiteness, and seemed to be covered with snow. The circumference of the berg was estimated at between three and four hundred feet, and its height at fifty; but, to judge from its shape, it is probable that little more than a sixth of its actual bulk was visible above the surface of the ocean. |

Floating ice-islands are not unfrequently seen in this latitude, and the uncertainty of their situation requires that ships should keep a strict night-watch to avoid them. During the winter season they remain consolidated with the frozen lands whence they originate; and it is not until the summer of the south that they drift into the lower latitudes, and intrude upon the ordinary tracks of shipping. Many penguins, and divers, were at the same time observed swimming on the water; their home being either the iceberg, or, with more probability, the Falkland Islands, from which we were now distant about a day's sail. January 14. – Attained our highest south latitude, namely, 58° 33' in long. 69° W.; when, being to the S. W. of Cape Horn,* and in the Pacific Ocean, the ship's course was altered to the N. W. Although the season was midsummer, we found the temperature of this region unpleasantly low; – showers of snow and sleet * The island at the southernmost extremity of the American continent, and known as "Cape Horn," is placed in lat, 55° 58' 30" S., long. 67° 21' 14" W. Its name is derived from the Dutch galliot Horne, commanded by Wilhelm Schouten, and engaged in an expedition under the direction of Jacob le Maire, in the Eendracht; when the latter vessel rounded this cape, and gave to it the name of her consort – the Horne having been previously burned in Port Desire, December 19, 1615. |

were frequent; and winds from the southward brought with them the piercing coldness of a frosty day in the winter of England; a state of atmosphere which was strangely contrasted with the extreme length of the days. The barometer, also, maintained a very low grade, on no occasion marking 30, and often falling to 29.20, without any accession of foul weather. Towards sunset, the sky to the southward occasionally presented the white and luminous reflection termed "ice-sky," or "ice-blink." On the evening of the 17th, the sun, setting behind a dark cloud-bank, cast a lovely vermilion tint over numerous small and higher nebulae; while immediately over the spot of its descent was pictured a very perfect parhelion, or "mock-sun," at the height of about four degrees above the horizon. It presented the appearance of a small orb of deep red colour; and continued visible, with various gradations of brightness, for fifteen minutes. January 19. – We rounded Cape Horn, or attained to the northward and westward of its promontory; and continued our route to the northward, off the coast of Patagonia. In lat. 48° S., long. 80° W., the surface of the ocean presented extensive fields of a red colour, which proved to be formed by myriads of me- |

dusae, of the genus Salpa. As we passed through the coloured water we captured vast quantities of these creatures. They were one inch in length, of broad and flattened form, transparent, and had a violet tint, resembling glass delicately stained with the oxide of manganese. When placed in a vessel of sea water, they moved actively, with a darting or jirking motion; and upon being held in the hand, exhibited, incessantly, the peculiar pulsating action of the sides of the body by which they propel themselves through the ocean. A very large flock of small sea-birds, resembling stormy-petrels, hovered over this tract of animated water, and occasionally alighted on its surface. In the vicinity of this spot we spoke the French ship Mississipi, of Havre, cruising in search of the southern true-whale. It was looked upon as an unusual circumstance that her master was a Frenchman; the few whaleships sent out from the ports of France being mostly commanded by Americans. Her crew, with the tact peculiar to their nation, were busily occupied in preparing complicated messes from the legs of the albatross, which they had captured in great numbers. We had ourselves, indeed, attempted a similar dish, prepared after the receipt of Captain Cook; but, although the |

flesh of this bird is not decidedly objectionable in flavour, we found it somewhat tough, and not altogether so good as to induce to a repetition of the experiment. In the afternoon of the same day, the sea, for some distance astern of the ship, was literally covered with aquatic birds, chiefly of the albatross family. Their number could not be estimated at less than some thousands. They had apparently been attracted to the spot by some oily matters floating on the water; while the rapidity with which they had been assembled by that cause would indicate that they possess great acuteness either of sight or smell. Among them was a bird I had never before, nor have since, seen. It was the size of a pintado-petrel; the beak yellow; the plumage black, with a white band passing across the upper and under surfaces of the wings. It flew rapidly, and with a short flapping action of the wings, unlike the flight of ordinary sea fowl; occasionally alighted on the sea; and when in the air attacked the albatrosses, who to escape its assaults invariably betook themselves to the water. During a dark and calm night, with transient squalls of rain, in lat. 43° S., long. 79° W., the sea presented an unusually luminous appearance. While undisturbed, the ocean emitted a faint |

gleam from its bosom, and when agitated by the passage of the ship, flashed forth streams of light, which illuminated the sails and shone in the wake with great intensity. A net, towing alongside, had the appearance of a ball of fire followed by a long and sparkling train; and large fish, as they darted through the water, could be traced by the scintillating lines they left upon its surface. The principal cause of this phosphorescent appearance was ascertained by the capture of numerous medusae, of flat and circular form, light-pink colour, and eight inches in circumference; the body undulated at the margin, spread with small tubercles on its upper surface, and bordered with a row of slender tentacles, each five feet long, and stinging sharply when handled. The centre of the under surface was occupied by a circular orifice, or mouth, communicating with an ample interior cavity, and surrounded by four short and tubular appendages, which, when conjoined, resembled the stalk of a mushroom – a plant to which the entire animal bore much resemblance in form. When captive, the creature displayed a power of folding the margin of the body inwards; but its natural posture in the water was with, the body spread out, and the tentacles pendent. |

When disturbed, this medusa emitted from every part of its body a brilliant greenish light, which shone without intermission as long as the irritating cause persisted, but when that was withdrawn the luminosity gradually subsided. The luminous power evidently resided in a slimy secretion which enveloped the animal, and which was freely communicated to water, as well as to any solid object. When thus detached, it could be made to exhibit the same phosphoric phenomena as the medusa itself; hence, it is reasonable to suppose, that the gleam of the ocean arose no less from the luminous matter detached from these creatures than from that which adhered to them; and I was further satisfied on this point, when I found that immersing the medusa in perfectly clear and fresh water communicated to that fluid all the scintillating properties of a luminous sea. Though the discovery of these medusae was a satisfactory explanation of the phosphorescent appearance of the water, I had yet to learn that the latter effect was partly produced by living, bony, and perfectly-organized fish: such fish were numerous in the sea this night; and a tow-net captured ten of them in the space of a few hours. They were a species of Scopelus, three inches in |

length, covered with scales of a steel-gray colour, and the fins spotted with gray. Each side of the margin of the abdomen was occupied by a single row of small and circular depressions, of the same metallick-gray hue as the scales; a few similar depressions being also scattered on the sides, but with less regularity. The examples we obtained were alive when taken from the net, and swam actively upon being placed in a vessel of sea-water. When handled, or swimming, they emitted a vivid phosphorescent light from the scales, or plates, covering the body and head, as well as from the circular depressions on the abdomen and sides, and which presented the appearance of as many small stars, spangling the surface of the skin. The luminous gleam (which had sometimes an intermittent or twinkling character, and at others shone steadily for several minutes together,) entirely disappeared after the death of the fish. In two specimens we examined the contents of the stomach were small shrimps. As we proceeded to the N. W., and the weather became more settled and agreeable, the ship was re-equipped for sailing in fair latitudes, and the mast-heads were again manned; a duty which had been omitted during our cold and boisterous passage round the Cape. |

On the 10th of February, a large and solitary sperm whale was seen moving leisurely through the water, at a short distance from the ship. The approach of night did not allow of the boats being lowered; but the clouds of vapour cast in the air as the cachalot exposed its dark form above the surface of the sea, the crew covering the rigging, and hailing each spout as it arose with "There again!" prolonged with a solemn and not inharmonious tone, and the moodv silence, so expressive of disappointment, with which they dispersed when the coveted animal was no longer visible, had a novel effect during a serene evening about the period of sunset. On the following day Juan Fernandez was in sight from the mast head, bearing N. N. W., and distant about sixty miles. As we approached it closely, this island presented a series of elevated and mostly conical mountains, extending east and west, and bearing a desolate, arid, and highly volcanic aspect, but little in accordance with the rich fertility for which the interior of the country is so remarkable. When at the distance of six miles from the coast we lowered two boats, and entered a channel, about three miles broad, which separates Juan Fernandez from a small insular spot named "Goat Island." This latter islet does not exceed four or five |

miles in circumference, and has a mountainous, burned, and barren appearance. Its height may be estimated at about four hundred feet. Its coast is precipitous, and composed of a brown volcanic stone, which presents, on the exposed surfaces of many of the cliffs, tortuous and columnar projections, resembling the branches and trunks of trees half imbedded in its structure. On the north side, and western extremity, a stream of fresh water empties itself into the sea over the face of the cliffs. With much impediment from a heavy surf, we effected a landing upon this island. Its soil afforded no vegetation higher than a stunted shrub and a few patches of verdure served rather to heighten by contrast, than to relieve, the general sterility of its appearance. Neither goats (which are said to have formerly abounded on this spot) or any other quadrupeds were visible during our stay. The birds we noticed were terns, boobies, and other of the amphibious tribes peculiar to such coasts; bluepigeons, resembling our stock-dove, (Columba oenas,) nestling in the precipices; flocks of small birds, the size of a wren; and one species of falcon. Vast numbers of violet-coloured crabs occupied the rocks, and, by the threatening attitudes they assumed, appeared to dispute with us the pos- |

session of the coast. Fish were plentiful in the waters around, and took the hook so readily that in less than two hours the boats were enabled to obtain an ample supply for our ship's company. They were chiefly of the kinds known as "rockcod," "snappers," or gilt-heads, (Sparus,) "sweeps, " (Glyphisodon,) and "rudder-fish," or scad. (Caranx.) Large eels were also numerous, but proved so tenacious of life, hideous in aspect, and prone to bite, that we were glad to dismiss them from the boat as soon as they were captured. Juan Fernandez is about twenty-four miles in circumference, and has an elevation of 3000 feet above the level of the sea. It was formerly employed as a penal settlement from South America; but of late years a disposition has been shewn to colonize its shores from the republic of Chili. The harbour of Cumberland Bay, on its N. E. side, affords good anchorage, and some supplies for shipping; although the ill discipline displayed by the convict residents has deterred many vessels from availing themselves of its advantages. On the evening of the 12th, we made sail from this island, and steered to the northward and westward, until in lat. 25° S., long. 87° W.; when we commenced a due West course. Mo- |

derate winds from S. E., and fine weather, now attended our progress; but, owing to the sudden transition from the coldness of high latitudes to the mild climate on the verge of the tropics, catarrh attacked our ships company with a prevalence and severity that gave it some claim to the title of epidemic influenza. |

CHAPTER II.

At daylight on the 7th of March, the dark and elevated form of Pitcairn Island was seen from the mast-head, bearing W. 1/2 S. by compass, and distant about thirty-five miles. Calms, or light airs, did not permit us to approach the land closely until after sun-set; when the ship was hove-to for the night, and a gun fired and a blue light burned, in answer to the signal-fire kindled by the inhabitants on the hills. On the succeeding morning we made sail to within five miles of the northern coast, (where some houses on the heights denoted the situa- |

tion of the settlement,) and lowered a boat, in which Mr. Stolworthy and myself accompanied Captain Stavers to the shore. Guided by the gestures of a native, who stood upon an eminence waving a cloth, we proceeded for an indentation of the coast, where several of the islanders were collected on the rocks; but here so heavy a surf broke upon every visible part of the shore that some reluctance was felt to expose the boat to its fury. While we were considering the best mode of effecting a landing, one of the islanders plunged into the sea and swam towards us. He approached with the salutation, "Good morning, brethren," and, entering the boat, commenced a familiar conversation in very good English. Upon his volunteering to pilot us to the landing-place, and, in his own words, "to be responsible for the safety of the boat," the crew again took to their oars; when passing through a line of heavy rollers, and doubling a projecting ledge of rocks, we almost immediately entered comparatively tranquil water, and ran the boat's bow upon the small beach of "Bounty Bay," where some pigs of iron ballast, and shreds of corroded copper, yet remain as mementos of the fate of the vessel which has given her name to the spot. The principal |

male inhabitants received us on the beach with a cordial and English welcome to their shores, and conducted us by a steep and winding path to the settlement. Several of the heads of families we had not before seen, and groups of women and children, met us on our way, their countenances beaming with pleasure at the appearance of their visitors, and all of them desirous to shake hands with their "countrymen," as they term the British. They had seen the ship since the previous morning, and had been anxiously awaiting our arrival. This island is lofty, though of limited extent; its circumference does not exceed seven miles; while its extreme height, as determined by Captain Beechey, is 1046 feet above the sea. The coast is abrupt and rocky, beaten by a heavy surf, and closely surrounded by blue water of unfathomable depth. No harbour obtains; but small vessels may find anchorage in twenty-five, and twelve fathoms water, with sandy bottom, close to the western shore. A difficult, but practicable landingplace, corresponding to this anchorage; a second at Bounty Bay; and one (more questionable) on the S. E. coast, are the only points where the island is accessible from the sea. Coral grows on the coast, and its debris are found |

on the coves; but there are no distinct reefs of this material. The northern side of the island, or that occupied by the settlement, offers a very picturesque appearance; rising from the sea as a steep amphitheatre, luxuriantly wooded to its summit, and bounded on either side by precipitous cliffs, and naked and rugged rocks, of many fantastic forms. The simple habitations of the people are scattered over this verdant declivity, and are half concealed by its abundant vegetation. They are neatly constructed of plank, thatched with leaves of the screw-pine, (Pandanus fascicularis,) and provided with windows, to which shutters are affixed. The greater number have but a single apartment, occupying the entire interior of the building, and floored with boards; while some few (called double-cottages) possess an upper-room, which communicates by a ladder with the one beneath. The furniture they contain is scanty and of the rudest description; nevertheless, every thing about them denotes great attention to cleanliness and order. The dwelling formerly occupied by old John Adams is a neat cottage, containing two apartments, both of which are on the ground. It is situated in a pleasant and elevated part of the |

village, and opens with pretty effect upon a smooth and verdant lawn. The largest and best building the settlement can boast is that named the school-house, and applied to the purposes of a church, school, and teacher's residence. To each cottage is attached a plot of garden-ground, fenced round with roughly-hewn stakes, and planted with water-melons, sweet potatoes, and gourds; while cattle-sheds, pigsties, and other outhouses, herds of swine and goats, and many European implements of agriculture, (including some wheelbarrows,) afford a rural picture that forcibly reminds the Englishman of similar scenes in his native land. Many good paths, conducting to the habitations and cultivated lands of the natives, intersect the settlement, and often pass through dense and solemn groves of majestic banian trees. (Ficus indica.) The fabric of this island is chiefly a dark volcanic stone, but on the northern coast I observed some cliffs of a yellow and friable sandstone. The whole of the fertile soil (which is rich, and composed of a red clay mingled with sand) was originally shared, in nearly equal proportions, by the settlers from the Bounty, and is now retained in like manner |

by their descendants; each family possessing a small estate and subsisting upon its produce. A comparative scarcity of water exists, since there are no natural streams, and the volcanic structure of the land precludes the formation of wells; but rain-water is largely received in ponds or tanks, and it is not until rain has been absent seven or eight successive months that the residents experience any material inconvenience from this cause. The greatest supply of water is still obtained from a natural excavation which was discovered by William Brown, the assistant botanist of the Bounty, and thence named "Brown's Pond." It is supposed to possess a spring. At this time the population consisted of eighty persons,* of which the majority were * One of the females, Jane Quintal, had left the island, in company with an English sailor, some years previous to our visit. Her paramour left her at the island of Rurutu, or Oetiroa, where she married a native, and continued to reside. My brother, Mr. G. Bennett, thus describes an interview he had with this female during his stay at Rurutu, in September, 1829: "On the beach I was accosted by a tall, fine, half-caste woman, dressed in neat European clothing. Her manner was artless, and she spoke the English language with correctness. She informed me that her name was Jane Quintal, of Pitcairn's Island. |

children, and the proportion of females greater than that of males. The entire race, with the exception of the offspring of three English men, resident on the island and married to native women, are the issue of the mutineers of the Bounty, whose surnames they bear, and from whom they have not as yet descended beyond the third generation. So strong a personal resemblance obtains between the members of a family that it is no difficult task to distinguish brothers and sisters. I was particu- 'You have heard of Matthew Quintal?' she said: 'I am his daughter.' The following conversation then took place between us: – 'How long is it since you left Pitcairn's Island?' – A few years ago, in a whale-ship.' – Why did you leave?' – 'There are no husbands there; and besides,' she continued, 'the island is too small for us. It is, sir, but a very small island; quite a rock.' – 'You are married now, I suppose?' seeing a little chubby dark urchin in her arms. – 'Yes,' she replied; 'I married a native of this island (Rurutu). I was obliged soon to get married, they are so very particular; all missionaries. I could not talk to any male creature when single, so I got married.' – 'Do you wish to return to Pitcairn's Island?' 'No, I am very comfortable here.' Having ascertained that I was in the medical profession, she made me promise to send her 'stuff to raise a blister,' sticking-plaster, &c. as she intended to practise the profession herself on the island." |

larly led to notice a predominance of Irish features in many among them, and more especially in the fair and expressive countenances of some of the children; nor had I any reason to be dissatisfied with my skill in national physiognomy, when I was afterwards informed that these individuals bore the name of M`Coy, and were the issue of one of the Bounty's crew who was an Irishman.* The only survivors of the first settlers are two aged Tahitian females, who possess some interest, in association with the history of these islanders. The eldest, Isabella, is the widow of the notorious Fletcher Christian, and the mother of the first-born on the island. Her hair is very white, and she bears, generally, an appearance of extreme age, but her mental and bodily powers are yet active. She appeared to have some knowledge of Capt. Cook, and relates, with the tenacious retrospect of age, many minute particulars connected with the * I subsequently noticed a similar fact at Tahiti; where an intelligent half-caste woman, the offspring of a female of Borabora and an Irishman, was principally to be distinguished from the ordinary natives by her strongly-marked Hibernian features. Upon my mentioning this peculiarity in her countenance to a friend residing on the island he informed me of her origin. |

visits of that great navigator to Tahiti. The second, Susan Christian, is some years younger than her countrywoman Isabella. She is short and stout, of a very cheerful disposition, and proved particularly kind to us; indeed, I flattered myself that I had found favour in the sight of "old Susan," as she not only presented to me a native cloth of brilliant colours, which she had herself manufactured, but, bringing a pair of scissors, insisted upon my taking a lock of her dark and curling hair, flowing profusely over her shoulders, and as yet but little frosted by the winter of life. This woman arrived on the island as the wife of one of the Tahitian settlers, and bears the reputation of having played a conspicuous part when the latter were massacred by their own countrywomen. She subsequently married Thursday October, the eldest son of Fletcher Christian, and who died at Tahiti in 1831. Her daughter, Mary, a young and interesting female, is the only spinster on the island; she perseveres in refusing the offers of her countrymen, to whom she expresses great aversion, but, unfortunately, her antipathy has not extended to Europeans, and a very fair infant claims her maternal attentions. In person, intellect, and habits, these islanders form an interesting link between the civilized |

European, and unsophisticated Polynesian, nations. They are a tall and robust people, and their features, though far from handsome, display many European traits. With the exception of George Adams, who is much fairer than any of his countrymen, the complexion of the adults does not differ, in shade, from that of the Society Islanders. Their hair, also, is invariably black and glossy, and either straight or gracefully waved, as with the last-named people. Their disposition is frank, honest, and hospitable to an extreme; and, as is common to races claiming a mixture of European with Asiatic blood, they possess a proud and susceptible tone of mind. In conducting the most trivial affairs they are guided by the Scriptures, which they have read diligently, and from which they quote with a freedom and frequency that rather impair the effect. A modest demeanour, a large share of good humour, and an artless and retiring grace, render the females peculiarly prepossessing. Some of the younger women have also pleasing countenances; but, on the whole, little can be said in favour of their beauty. They bear an influential sway both in domestic and public politics; and this they are the better calculated to do, since they are intelligent, active, and |

robust, partake in the labours of their husbands with cheerfulness, and, with but few and recent exceptions, live virtuous in all stations of life. Their children are stout and shrewd little urchins, familiar and confident, but at the same time well behaved. They are early inured to aquatic exercises; and it amused us not a little to see small creatures, two or three years old, sprawling in the surf which broke upon the beach; their mothers sitting upon the rocks, watching their anticks, and coolly telling them to "come out, or they would be drowned;" whilst the older children, amusing themselves with their surf-boards, would dive out beneath the lofty breakers, and, availing themselves of a succeeding series, approach the coast, borne on the crest of a wave, with a velocity which threatened their instant destruction against the rocks; but, skilfully evading any contact with the shore, they again dived forth to meet and mount another of their foaming steeds. The ordinary clothing of the men is little more than the maro, or girdle of cloth, worn by the most primitive Polynesian islanders. On occasions of ceremony, as to attend at church, or receive the visits of strangers, they assume a complete English costume; their hats being constructed of pandanus-leaf cinnet, and de- |

corated with coloured ribbons, which give them a pretty rustic-holyday effect. The females commonly employ for their dress the native material they prepare from the bark of the paper-mulberry tree, stained with vegetable dyes; but, as opportunities offer, they substitute for this rude cloth the handkerchiefs and cotton prints of Europe. They wear the petticoat and scarf in the Tahitian style, and complete their toilette after the manner of the same nation, by passing a girdle of the seared and yellow leaves of the Ti plant around their waist; placing flowers in their ears; and encircling their tresses with a floral wreath. Some few wear their hair short; but the majority permit it to flow over their shoulders in luxuriant ringlets. These people subsist chiefly on vegetable food. Yams, which are abundant and of excellent quality, form their principal dependence; and next to these the roots of the mountain-taro (Arum costatum), for the cultivation of which the dry and elevated character of the land is so well adapted. Cocoa-nuts, bananas, sweet-potatoes, pumpkins, and water-melons, are also included among their edible vegetables; but of bread-fruit they obtain only a scanty crop, of very indifferent quality. They prepare a com- |

mon and favourite food with grated cocoa-nuts and yams, pounded, with bananas, to a thick paste; which, when enveloped in leaves and baked, furnishes a very nutritious and palatable cake, called pilai. On two days in the week they permit themselves the indulgence of animal food, either goat's flesh, pork, or poultry; while the waters around the coast afford them a sufficient supply of fish. They cook in the Tahitian manner, by baking in excavations in the earth, filled with heated stones; the fuel they employ is usually the dried husks of the cocoa-nut. The elder members of the Pitcairn Island family are but indifferently educated; scarcely any of them being able to write their own name, though most can read. For some years past, an Englishman, named George Nobbs, has resided on the island, and officiated as schoolmaster to the children, who, in consequence, exhibit a proficiency in the elements of education highly creditable both to their own intelligence and to the exertions of their teacher. George Adams had commenced instructing himself in writing but a few months before our arrival, and a journal which he had kept for that length of time, and which he put into my possession, displays much progress in the art. |

The few books they possess have been obtained from sailors visiting their shores, and are chiefly of a religious tenor. Some volumes, also, which were removed from the Bounty are still preserved in the house formerly occupied by the patriarch John Adams. The English and Tahitian languages are spoken with equal fluency by all the islanders, excepting the two Tahitian females, who speak little else than their native dialect, and are, perhaps, in the sad predicament of having partly forgotten that. They converse in English with some of the imperfections peculiar to foreigners; and this may be partly attributed to their usually discoursing in Tahitian with one another; as well as to a practice among their British visitors of addressing them in broken English, the better to be understood – a delusion into which most fall upon their first intercourse with this people. They, nevertheless, -pride themselves upon an accurate knowledge of the language of their fathers; and not only aim at its niceties, but also indulge in the more common French interpolations, as faux pas, fracas, sang froid, &c. They were early and well instructed in the pure doctrine of the Christian religion by their revered forefather John Adams; and it is to be sincerely hoped that no fanaticism may ever |

intrude upon their present simple and sensible worship of the Creator, nor the intemperate zeal of enthusiasts give them a bane in exchange for that religion, "Whose function is to heal and to restore, Their sabbath is now observed upon the correct day, or that according with the meridian of the island; which was not the case in 1814, when Sir T. Staines visited the spot, and found John Adams and his small community preserving Saturday as the day of rest; an error which had arisen from the circumstance of the Bounty having made the passage from England to Tahiti by the eastern route, without any correction of time having been made to allow for the day apparently gained by this course. The canoes the natives possess are but few, and of very simple construction. They are hollowed out from one piece of wood, and each is adapted to carry two persons. When afloat, they appear as mere wooden troughs, or little better than butcher's trays; nevertheless they can brave a very rough sea, or go safely through a heavy surf, and, when managed by their island owners, cleave the water with incredible velocity. The young men of the island are excellent divers. They occasionally engage themselves |

to pearling vessels, to dive for pearl-shell among the adjacent islands; with an understanding that they are to be restored to their home at the expiration of their engagement. At the period of our visit the climate of Pitcairn was serene and delightful, and, though the thermometer marked 82° in the shade, the sensible temperature was kept agreeably low by the moderate and refreshing trade-winds, which almost incessantly blow over the land. Winds from N. W., with wet and squally weather, are occasionally experienced; but no season is considered remarkable for rains. The land has generally a very salubrious aspect, and the inhabitants a very healthy appearance; nor are there, apparently, any diseases endemic amongst them. Elephantiasis, or fefe, so prevalent in many of the islands of the Pacific, is here unknown. The natural productions are principally those common also to the Society Islands. The quadrupeds we noticed were all exotic, as goats and swine, which were brought hither by the first settlers from the Bounty; and a bull and cow, a donkey, a dog, and several cats, which the people had recently brought with them from Tahiti; but, as the island affords but little pasturage, the oxen had destroyed some fruit-trees, |

and it was determined that they should be killed. The domestic fowls are of the breed introduced here by the Bounty. Some Moscovy ducks had been lately left on the island by the Hon. Capt. Waldegrave, of H. B. M. S. Seringapatam. The only wild birds we observed, beyond the amphibious denizens of the coast, was a small and noisy species inhabiting the woodlands; in size and plumage it resembles our common sparrow, and it bears the same name amongst the islanders. Small and active lizards, of many gaudy hues, are numerous on the vegetated lands. Among the insects, mosquitoes have but lately made their appearance, and are supposed to have accompanied the islanders upon their return from Tahiti. The breadfruit, it is said, was found on this island by the Bounty's people, who also introduced many plants of it from Tahiti; it was formerly plentiful, but the trees are now few in number and bear but a small and annual crop of fruit. This degeneracy is believed by the natives to attend upon the clearance of the land; and such may probably be the fact; but, at the same time, the dry, elevated, and exposed character of the soil, is so opposed to the natural habitude of this tree in other parts of Polynesia |

that I am only surprised to find it ranking with the indigenous vegetation. The candle-nut tree, and Indian mulberry, are conspicuous in the wooded lands. The roots of the former are used by the people to give a brown, and those of the latter a yellow stain to their bark cloth. The lime tree (Citrus medica) has been introduced, but is not prolific; nor has the mountain-plantain, (Musa fei,) recently imported from Tahiti, as yet succeeded. The cotton shrub, (Gossypium vitifolium,) loaded with large and globular pods containing much excellent wool; capsicum, or bird-pepper, (Capsicum frutescens,) sugar cane, tobacco, and turmeric, grow wild in great abundance, but are applied to no useful purpose. The residents say that the cultivation of the sugar-cane is opposed by rats, which infest the soil in great numbers, and destroy the young plantations. Yams (Dioscorea sativa and aculeata) are indigenous to the island, and cultivated with much care. They are grown in fields, or "yam patches," on the exposed and sunny declivities of the hills, their vines wandering procumbent over a great extent of ground. They produce an annual crop of roots; the season for planting |

them commencing in October, and that for digging between July and August. One large root, when cut for seed, is estimated to produce twenty plants. The labours of hoeing and preparing the earth, sowing the seed, transplanting the seedlings, and digging for the mature roots, are the greatest these islanders have to contend with, and furnish as many data for the events of their lives. The mountain taro (Arum costatum) is also indigenous, and is very generally cultivated on the dry and elevated lands, where it occurs as verdant plots of tall, erect, and arrow-shaped leaves, bearing in their centre the flowers peculiar to the "wake robin" family. Unlike its aquatic congener, A. esculentum, or common taro, this species prefers a dry and mountain soil, or is, at least, conveniently amphibious. The cultivated root attains a large size and bears some resemblance to the yam, and, although when in the raw state it is so acrid as to excoriate the skin, when cooked it affords a very agreeable and nutritious food. The Irish potatoe is occasionally grown; but the natives give the preference to the cultivation and use of the sweet potatoe (Convolvulus batatas). Amongst the miscellaneous vegetation, we observed the scurvy-grass of navigators (Carda- |

mine antiscorbutica); and the ferns Asplenium obtusatum, Acrostichum aureum, an undescribed species of Hymenophyllum, and a species of Cyathea, a tree-fern attaining the height of from twelve to fourteen feet. The most abundant pasture-grass is a species of Eleusine. It is probable, that Pitcairn Island was seen as early as January, 1606, by the Spanish commander, Louis Paz de Torres; although the date of its discovery may with more certainty be referred to 1767, when its existence was ascertained by Captain Philip Carteret, of the British discovery-sloop Swallow. Captain Carteret did not land upon its shores, (which he had reason to believe were uninhabited,) and named the island after a young gentleman on board his ship, by whom it was first seen. In the year 1773, Captain Cook, then engaged on his second voyage, cruised in diligent search of this land, but failed to find it; Captain Carteret having laid it down more than three degrees to the westward of its true position.* The second recorded visit to Pitcairn Island is * Sir T. Staines determined the position of this island to be lat. 25° S., long. 130° 25' W. Capt. Beechey, R. N. has fixed the position of its village in lat. 25° 3' 37" S., long. 130° 8' 23" W. |

that of the British armed-ship Bounty and her mutinous crew, in 1790. The events which occurred on board this vessel, while under the command of Lieut. Bligh, and employed in conveying plants of the breadfruit from Tahiti to our West India colonies, are well known; nevertheless, I maybe permitted to relate, briefly, the ultimate fate of both the vessel and her crew, in connexion with some facts that came under our notice, and with others communicated to me by the Pitcairn islanders, or by the English residents who had for many years lived in social intercourse with John Adams, the late patriarch of the colony. Upon leaving Tahiti for the last time, in September, 1789, taking with them several natives of that island, the mutineers in the Bounty are known to have steered to the N. W.; but their route must have been long and devious, since it was not until January 1790, that they reached Pitcairn Island, a distance of little more than four hundred leagues from Tahiti, in a S. E. direction. Whether Christian, who had the command of the ship, made this small and sequestered isle by accident or design I have been unable to ascertain; but if from a previous knowledge of its existence, it is evident he could have reached it only upon a parallel of latitude, |

as its correct longitude was at that time unknown. When off this land, the ship was nearly lost to Christian by a counter conspiracy. He had landed with some Tahitians to inspect the country, when Mills, the gunner's mate, proposed to those who remained on board to make sail for Tahiti, and leave their companions on shore to their fate; but some unexplained circumstances did not permit this plan to be carried into execution. Finding the island adapted to their purpose, (and certainly few spots in the Pacific could have been better so,) the mutineers kept the ship lying close off the coast, while they removed, in casks and on rafts, the stores they wished to preserve.* This had been but partially effected when one of the crew, named Matthew Quintal, set fire to the vessel, without the sanction of his shipmates, and contrary to the wish of Christian. The ship, while in flames, drifted to the shore, and her destruction was completed in Bounty Bay. What portions of her wreck remained, or were subsequently cast up by the sea, were carefully collected and destroyed, to remove from the * Tradition amongst the islanders yet records the delight of the Tahitian females when they received the sails of the Bounty, to make their clothing from the canvass. |

ocean every trace of her fate.* For some time after they had landed, the mutineers were tormented by the fear of detection, and kept a constant watch on the summit of a lofty cliff, which immediately strikes the observer as being admirably adapted for that purpose, and which is, indeed, still employed as a look-out station by the inhabitants. From this commanding height they observed, soon after their arrival, a sail approach the land; but did not believe that she neared it sufficiently to communicate by boat. They subsequently ascertained, however, that some persons had landed from her, and returned, probably under the impression that the island was uninhabited. The fate of this small band of colonists (which consisted of fifteen men and twelve women) was retributive and melancholy in the extreme. All of their number met with violent deaths, except- * The present race of people speak of the bark of their fathers with much interest. They showed us many of her relicks, and from among them we obtained a blank log book, of antiquated appearance. On the interior of its cover was a card, engraved with fanciful devices, a coat of arms, with the motto "Pro Deo patria et amicis," and a scroll, bearing the name of Fran. Hayward, which would declare the owner of the book to have been one of the midshipmen of the Bounty who accompanied Lieutenant Bligh in the launch. |

ing Adams, Young, and some of the Tahitian females. Fletcher Christian and John Mills were shot on the same day, by the Tahitians; the grave of the former was pointed out to me: it is situated a short distance up a mountain, and in the vicinity of a pond. Isaac Martin ..... Williams, and William Brown, shared a similar fate. Several of the Tahitian men fell also in these conflicts; and the survivors, when in a fair way to exterminate their British rivals, were themselves slaughtered, "at one fell swoop," by their own wives and countrywomen. Matthew Quintal, whose temper was uniformly tyrannical and quarrelsome, was shot by his comrades, who, it is charitable to believe, were compelled to resort to that measure in self-defence. William M'Coy became delirious (partly, it was thought, through remorse for the part he had taken in the destruction of Quintal,) and drowned himself in the sea, with a stone tied round his neck. Brown, Martin, and Williams died without issue. Mills had an only son, who was killed by a fall from a cliff, and one daughter, who is married into the family of the Youngs: the other mutineers have perpetuated their names through a numerous Anglo-Tahitian progeny. After the lapse of a few years, John Adams was left the only survivor of the British settlers, |

and the father of a young and happy community. He had served as an able seaman on board the Bounty, under the name of Alexander Smith, but his real name is Adams, Alexander Smith being a fictitious, or "purser's" name, assumed upon shipping, a practice very usual with British seamen. He was an Englishman by birth, and the son of a waterman, an occupation until very recently, if not at present, followed by his brother on the river Thames. He was accustomed to say, that a proposal to join in the mutiny was made to him as he lay in his hammock, and to this he acceded, but took no very active part in the atrocity. He was thrice married to Tahitian females. By his first wife, who accompanied him from Tahiti to Pitcairn's Island, he had no family. Upon her death he lived with, but did not marry, a female whom he took from her Tahitian husband; and this act (which has always been incorrectly ascribed to Fletcher Christian) led to the sanguinary dissensions between the mutineers and the men of Tahiti. His second wife was the widow of Mills; the fruits of this union were three daughters, now living in the island, namely, Dinah, married to Edward Quintal; Rachel, the wife of an Englishman named John Evans; and Hannah, the widow |

of George Young, who perished during the late residence of this people at Tahiti. Adams's second wife died of an injury she received from a goat while enceinte; and the widow of M'Coy became his third. By her he has an only son, George, who is married to Polly Young, the finest and most intelligent woman on the island. In March, 1829, John Adams expired, in the sixty-eighth year of his age, and after a residence of thirty-nine years on Pitcairn's Island. His remains, as well as those of his last wife (who had been for many years blind and bedridden, and who did not survive him more than six weeks) are deposited in separate graves, within an enclosure but a few yards distant from their former residence. Poplar-leaved hibiscus trees, covered with large yellow flowers, and a shrub of Poinciana pulcherrima, bearing clusters of crimson blossoms, shade the spot, and a rough head-stone distinguishes the grave of the patriarch from that of his wife. The particulars of the discovery of the Pitcairn colony, through visits accidentally paid to the island, in 1808, by the American ship Topaz, Captain Folger, and in 1814, by the British frigates Briton and Tagus, are sufficiently well known. John Adams, a short time before his death, |

had expressed apprehensions that the supply of water on his island would be inadequate to the wants of an increasing population; and that it might become necessary, hereafter, to request the aid of the British government to remove the colony to some other spot better adapted for its maintenance. In February, 1831, H. M. sloop Comet, Captain Sandilands, arrived at Pitcairn's Island, accompanied by the Lucy Anne transport, for the purpose of removing the residents to Tahiti, if such should prove to be their wish. The islanders, being partly actuated by a desire to visit the land which their mothers had depicted to them in glowing colours, but more by the fear that they should offend did they not accede to what they considered was the desire of the English government, consented to the proposed emigration. In four days they were all embarked, to the number of eighty-seven, on board the transport, and, escorted by the Comet, proceeded to Tahiti. Their arrival. at their destined port occurred at a peculiarly unfortunate period – the Tahitians were then on the eve of a civil war; and, in addition to the scenes of strife and confusion this distracted state of the island displayed, the hitherto immaculate Pitcairnians |

were compelled to witness the gross and unbounded licentiousness habitual to the place, and at this period unrestrained even by the broad meshes of the local laws. This Land of Promise, also, offered the colonists but little that could compensate for the loss of their own fertile and picturesque isle, which, though small, was more than sufficiently large,* and, in a word – their home. Nevertheless, the commercial bustle of Tahiti had its charms; to the habits of the people they became but too well inured; and it is probable that the Pitcairnians would soon have become reconciled to their new abode, had not disease assailed them soon after their arrival, and relentlessly thinned their numbers. Dispirited by this unusual affliction, they became anxious to return to their native land, and applied to Captain Sandilands for a passage thither; but the Captain had no instructions to that effect, and soon after put to sea with the Comet; having first obtained from the Tahitian government a liberal grant of land, and the promise of six months' supply of provisions for the Pitcairn colony. With the aid of a sum * It is estimated, that Pitcairn Island can well support 1000 inhabitants. |

of money raised by subscription amongst the benevolent European residents at Tahiti, and by a part-payment of the copper bolts of the Bounty, the unfortunate emigrants were at length enabled to obtain a passage, in an American vessel, to their own shores, which they regained after an absence of little more than five months. Upon the occasion of this disastrous expedition, fourteen of their number perished by disease; twelve having died at Tahiti, and two others immediately after their return to Pitcairn Island. At the time of our visit nearly two years had elapsed since the return of this people: their lands were again in a high state of cultivation, and their former simple habits were in a great measure resumed. But the injurious effects of a more extensive intercourse with the world were but too evident in the restless and dissatisfied state of many amongst them, as well as in a licentiousness of discourse, which I cannot believe belonged to their former condition. Events had also occurred, shortly before our arrival, which had roused the worst passions of this hitherto peaceful race, and had divided the island into two factions, opposed to each other with a rancour little short of open warfare. The origin of this calamity was attributed to |

the recent arrival on the spot of an elderly Englishman, named Joshua Hill, who, uninvited, and without authority, had assumed, under the title of teacher, the government of the people. To strengthen his authority, he had allotted a subordinate share of it to a few of the most ambitious and athletic amongst the men, who, as "elders" and "privy council," were to enforce his regulations among their countrymen. The fraternal equality that had hitherto existed in their society was thus destroyed; while new laws, enforced under the equally new penalties of imprisonment and flogging, as well as by espionnage, and the seizure of fire-arms from the disaffected – measures at all times deemed more military than civil – naturally tended to irritate those of the natives who were not of the upper party, and many of them were anxious to accompany us to Tahiti, that they might escape such unpleasantries. George Adams, in particular, appeared much distressed at the state of his country, and urgently desired the presence of a British ship of war, to settle their disputes and "take old Hill and the muskets off the island." In this, as in many similar dissensions, it was difficult to determine to which party the greater share of blame should attach; for though no |

excuse can be offered for Mr. Hill's unauthorised intrusion upon the affairs of the island, or for his despotic measures, yet, previous to his arrival, the state of the island was confessedly bad, and the people much in need of a prudent governor. Immediately after their return from Tahiti, the pernicious practice of distilling an ardent spirit from the Ti root had become frequent – drunkenness and disease were amongst them – their morals had sunk to a low ebb and vices of a very deep dye were hinted at in their mutual recriminations. But all these errors might doubtless be eradicated by mild and judicious measures; and probably by the fortiter in re of Mr. Hill; though it is much to be feared that the social compact which formerly bound this people has been broken by the rude contact of the world, and that virtue and tranquillity have fled the spot, never more to return. I thought it, indeed, a remarkable proof of the mutability of human affairs, that these islanders, whom I had ever been accustomed to regard in the light of a curious phenomenon in the moral history of man – as a large and united family, occupying a sweet little isle of its own, remote from the contentious world, and rich in every Christian virtue, should prove, when seen on their own shores, the only |

one, of the many races of people we visited during the voyage, with whom discord prevailed. Notwithstanding these political disputes, and the part we were necessarily called upon to take in their discussion, the reputation for hospitality which has ever been attached to these islanders was not lost. Their best houses, their choicest food, and all that they possessed and deemed acceptable, were freely offered for our use; while fruits, vegetables, hogs, and fowls, were abundantly supplied to the ship. Some of the inhabitants accompanied us over the island, pointing out every object worthy of notice, and communicating information readily and with intelligence; while others went off in their canoes to the ship, that they might be presented to the English ladies, who they were informed we had on board. In return for their ample supplies and many acts of kindness, we presented them with such European manufactures as they required, and, after a friendly parting, embarked to continue our voyage, taking with us three Englishmen, who had intermarried with the natives, and resided amongst them for many years, but who had suffered so much persecution during the late unhappy discords that they were glad to |

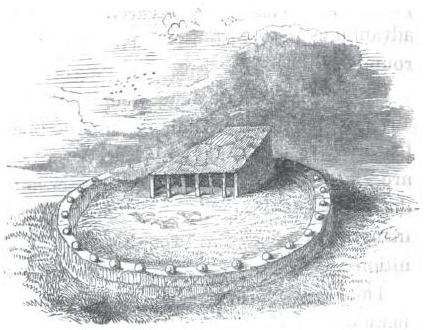

avail themselves of a passage to Tahiti, until they could return to their wives and families under competent protection.* There is every reason to believe that Pitcairn Island has had inhabitants previous to its occupation by the crew of the Bounty; since, in addition to the ruins of morais, images, &c. found on its soil, the islanders informed me that they had recently discovered two human skeletons, lying in the earth side by side, and the head of each resting on a pearl-shell. This last circumstance involves the history of the aborigines in yet greater obscurity; as the pearlshell, although found in the adjacent islands, has never been seen in the waters around Pitcairn Island. Stone adzes, supposed to have belonged to this ancient race, are not unfrequently found by the present inhabitants, whilst cultivating the ground. Two of these were given to me by Hannah Young, the third daughter of John Adams. They are rudely fashioned, in the ordinary Polynesian form of such instruments; are composed of a black * From the report of a visit to Pitcairn Island, by the Acteon, Lord Edward Russell, in 1836, we learn that Nobbs had returned, and resumed his office of schoolmaster; and that Joshua Hill had been recommended by his lordship to quit the island. |

basalt, highly polished; and bear an appearance of great antiquity. It is certainly difficult to account for the extinction of an original race upon a spot so replete with every essential for the support of human existence; and we are led to the hypothesis, that either one of the epidemic diseases, which occasionally scourge the islands of the Pacific, had destroyed the primitive inhabitants to the "last man," or that the island was but occasionally frequented, for religious or other purposes, by the people of some distant shore, who subsequently discontinued the custom. |

CHAPTER III.

From Pitcairn Island we continued our route to the N. W.; the winds holding chiefly from the northward, with wet and tempestuous weather – as is not unusual in this region during the autumn season. On the night of the 21st of March, the small but elevated and uninhabited island of Maitea, of the Georgian group, was seen, by moonlight, bearing N. N. E., distant ten miles; and early on the following morning Tahiti was observed from the mast-head, at the distance of about forty miles to the westward. As we approached the latter island, and sailed along its N. E. coast, the two lofty and elongated peninsulas of which it is composed had the appearance of as |

many distinct islands – the low isthmus, about two miles broad, which connects them, being invisible from the sea until very closely approached. The scenery commanded from this point of view fully justified the encomiums that voyagers have so liberally lavished upon it. The dark and cloud-capped mountains of the interior send to the coast a graduated series of undulating hills, their declivities, lightly timbered and covered with pasturage, exhibiting, as the sun plays upon them, many of the most beantiful variations of light and shade. Extensive vallies and plains, luxuriantly vegetated, intersect the mountain lands, and receive the waters of many glittering cascades, gliding majestically over the faces of the more precipitous heights; while in those spots where the huts and plantations of the natives can be detected amidst the foliage of the coast, relieving the natural wildness of the landscape, the effect is more enchanting than it is possible to describe. The day being far advanced when we reached the N. W. side of this island, the ship was kept lying off the coast until the following morning, when we received the native pilot on board, and, passing through the great reef, cast anchor in the harbour of Taonoa. |

Tahiti (Otaheite, Cook) is, correctly speaking, the largest of the six Georgian Islands, which are situated about seventy miles to the S. E. of a second group, discovered by Captain Cook, and named by him the Society Islands. It is now, however, very customary with voyagers, and others, to designate both the above clusters by the latter name; the Georgian being distinguished as the Windward, and the Society as the Leeward, islands. Of the two peninsulas which form the land of Tahiti, the northern and largest is named Opoureonu, or Tahiti-nue; the southern, Taiarabu, or Tahiti-iti. The entire island is estimated at 108 miles in circumference; and its population at 7000. It is separated from the rugged and mountainous island of Eimeo by a channel nearly eighteen miles across, and which permits free navigation between the reefs encircling the two islands. Notwithstanding the very mountainous character of Tahiti, extensive and fertile vales open upon the sea on all sides of its coast, giving passage to many broad and rapid rivers, abounding with fish. A broad belt of level alluvial soil, margined by a beach of fine sand or broken coral, encircles the greater portion of its shores and the entire land is clothed from |

the water's edge to its topmost heights with a perennial verdure, which for luxuriance and picturesque effect is certainly unparalleled. The highest mountain in this island is situated near its north extremity. It has never been ascended by an European, nor has any exact measurement of its height been given, but its estimated elevation above the sea is 7000 feet. Some Tahitians, who have gained its summit, report that they found there a lake of yellow water, (probably an extinct crater, with an ochreous sediment in the water it contains,) and some wild ducks, differing in plumage from the ordinary species indigenous to the coast. The principal settlements, and all those most frequented by shipping, are placed on the N. W. side of the island, on a tract of land about eighteen miles in extent, bounded to the eastward by the conspicuous promontory, Point Venus, and to the westward by Burder's Point. This space is divided into several districts, of which the principal spots and villages (as we proceed westward from Point Venus) are Matavai, Papaoa, Taone, Taonoa, Papeete, and Bunaauia. Matavai forms a distinct bay. Much of its soil is sandy and arid, the lofty mountains of the interior on the one hand, and a broad surf- |

beaten beach of black sand on the other, reducing its fertile and habitable land to a comparatively small space. Its southern boundary is formed by cavernous cliffs, at the base of Onetree hill,* its northern by the promontory on which Captain Cook observed the last transit of Venus across the sun's disk, in June, 1769, and hence named Point Venus. It is a long and sandy spit of land, divided through its entire length by a broad stream. On one side it is barren, or covered only with a profusion of the Convolvulus Braziliensis, while on the other it is adorned by a dense grove of cocoa-nut palms, presenting to the sea a very conspicuous landmark. The outer reef, which protects most other parts of the coast, is deficient at Matavai, or does not rise to the level of the sea by several feet; consequently the bay is exposed to a heavy swell during S. W. gales, and is not altogether an eligible anchorage. The coast between Matavai and Papeete is thinly inhabited; but affords extensive tracts of level and fertile soil, penetrating inland to the foot of the hills, covered with the wild fruittrees of the country, and enlivened by occasional herds of grazing cattle, and native huts embo- * The solitary Erythrina, or coral-tree, which formerly grew on the brow of this hill, and gave it a name, no longer exists. |