|

|

. . . .

STERN OF OLD "LEONIDAS," AT NEW BEDFORD. THE PERILS AND ROMANCE OF WHALING.1

WHENEVER, in any wars in which the United States has been engaged, a sudden increase in its naval force has become necessary, the Government has experienced no difficulty in at once manning the additions to its fleet with native sailors. Indeed many of the seamen who during the war for the Union went fearlessly aloft amid the smoke and flash of naval combat were descendants of the gallant souls who manned the, yards of the Bonhomme Richard, Lexington, and Constitution, and were, like their ancestors, American fishermen and whalemen. The whalemen especially have been the sinews of the American navy. Inured to danger by a calling in which the chances were as desperate as those of battle, they stepped from the whale-boat to the man-of-war simply to face a foe of a different kind. They needed no baptism under fire before they could meet an enemy without flinching, and when they responded to their country's call they grimly applied to each hostile ship the old whaling motto, "Dead whale or stove boat." Such was the spirit of the American whalemen, and it still survives not only among the veterans of the craft but also among their descendants, though the whaling industry itself has dwindled to insignificance. The Nantucket boy who ties a fork to his mother's darning cotton and then tries to harpoon the cat, yelling, as the latter makes its escape, "Pay out, mother! Pay out! There she sounds through the window!" is certainly worthy of the "boat-steerer" who was his sire. Then, too, we find in the vernacular of the old whaling ports, even among the younger generations, delightful relics of the whalers' idioms. The railroad train "ties up"; a wagon is a "side-wheel craft," and you are requested "to shift to windward" or "leeward" according as the sides need trimming; "Where are you heading for?" is the question invariably asked of you if you are met out walking; you learn 1 Much of the material for this article was gathered from log-books, old newspapers, and records in the possession of F. C. Sanford of Nantucket, Massachusetts. |

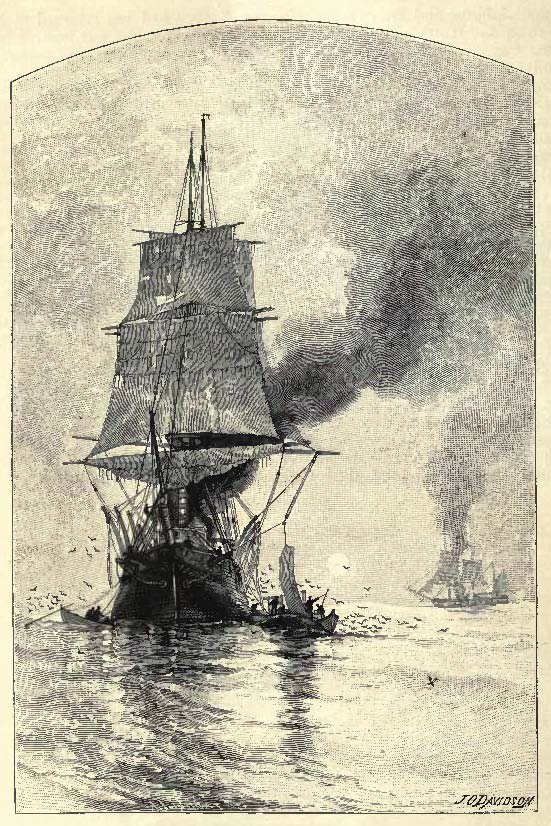

AN OLD WHALER. that your veteran whaleman neighbor of last summer died in the winter "in a flurry"; the farmer "lands" his produce at your "quarter-galleries" (meaning, in this instance, the rear kitchen, but also applied to that modern accessory of feminine attire, the bustle); you are instructed to "douse the glim" on retiring for the night; directed, if you cannot open the post-office door, to try turning the knob to the "westward," and if the door still refuses to yield are informed that probably the postmistress "has battened down the hatches" and gone "gamming." To" gam" means to gossip. The word occurs again and again in the log-books of the old whalers. The uninitiated might suppose it signified merely spinning yarns on the fo'castle. But to the old whaleman it has a far deeper meaning. When the whalemen met on the high seas thousands of miles from home they would lay to, sometimes for hours, captains and crew would exchange visits, letters from and for home be delivered, and the story of the voyages told. That was a "gam." One vessel |

often brought to another the first news from home in two years. Meanwhile, however, a year had elapsed since the vessel last from port left her moorings, and at least another year would pass before the homeward-bound crew would sight their native shore. No wonder the young captain, as his home harbor hove in sight, eagerly scanned the crowd upon the wharf through his marine glass until it rested perhaps upon a fair young face full of anxious expectation. Gamming is indeed a relic of one of the most romantic, and perhaps pathetic, phases of the whaler's life. Every vessel that sailed carried messages to relatives and friends thousands of miles away, and every vessel that came to her moorings brought tidings of cheer or sorrow from distant seas. A wife might have the letter which she had written to her husband two years before returned to her, because his vessel had not been spoken —and alas! she had not been spoken by any of the vessels that had returned during the year. Time would only deepen the mystery of her husband's fate, and perhaps the wife would never know whether the ship was cast upon one of the islands of the Pacific and the crew massacred by the savage inhabitants, or split upon a sunken reef and engulfed with all hands; and so she would sit weeping in her lonely chamber while her neighbors made merry over the return of a son, father, lover, or husband, and the streets rang with the songs of happy Jack. Whalemen returning home were liable to find that many changes had taken place during their long voyages. An old whaleman told me that he was obliged to sail on one of his voyages just after his mother's burial, leaving his father bowed down with grief. His vessel was hardly at her moorings three years later before said father slapped him on the back and said, "Alfred, come up to the house an' I '11 introduce you to your mother!" In many of the old whaling ports one may still hear snatches of "'Round Cape Horn," a song much in vogue in the days when the whaling industry was at its height. Following are a few characteristic stanzas:

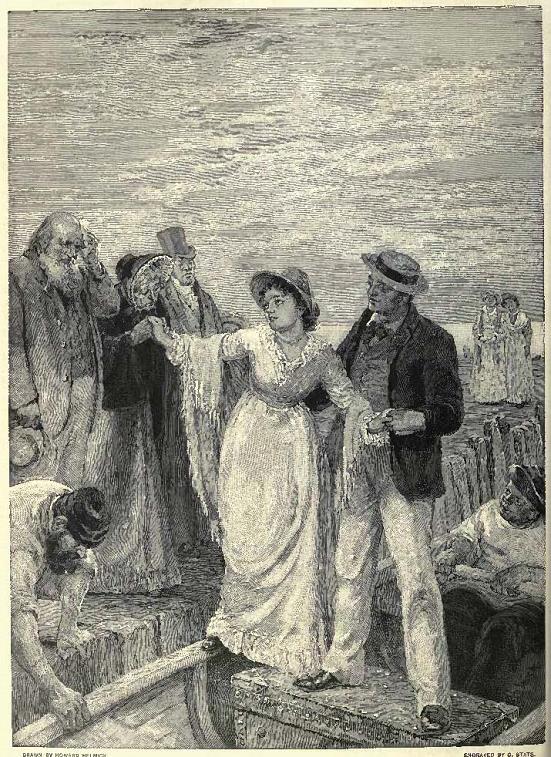

There is no exaggeration in these stanzas. The male population of the old whaling ports was divided into those who were away on a whaling voyage, those who were just returning from one, and those who were preparing to start on one. The youth who had not doubled "the Cape" was considered a nonentity, and had no more chance with the belles of Nantucket, New Bedford, or New London than a non-combatant has with those of a garrison town. Many a bride stepped from her home aboard her husband's whaler for a honeymoon on a three-years' whaling voyage"'round Cape Horn" and then north to the Arctic Ocean; to return perhaps with a toddleskin or two born at sea. For a whaler's wife to have been "'round the Cape" half a dozen times, or even more, was nothing extraordinary. A woman who had no children to keep her at home considered it her duty to share the perils of her husband's calling. One of these at least she could avert. The steward of a whaling vessel was generally some vicious, abandoned fellow who had a pleasant way, if the captain or one of the mates gave him offense, of spicing some dish served at the officers' mess with ground glass or poison. In many other respects the presence of the captain's wife doubtless made life in the cabin and on the quarter-deck more cheerful. I am credibly informed that one vessel, whose captain was usually accompanied by his wife and family, was equipped with a set of croquet which was put up on deck in seasons of calm, though scientific playing could scarcely have taken place on the sloping deck. As whaling voyages usually lasted several years, and the captain's authority was as absolute as his responsibility was great, the whaling industry with its many perils naturally developed men who seemed born to command — strong, active, and full of strategic resources, and never hesitating to enforce their rights. A better illustration of their proud spirit cannot be given than the encounter in Halifax between Greene, the mate of a Nantucket vessel, and the Duke of Clarence, admiral of the British fleet, and afterwards William IV. The dispute arose over the duke's attentions to a girl, and reached its climax in the Nantucket mate's seizing the future king of England and hurling him downstairs. An eye-witness of the affair was wont in after years to add as a decorative detail that the click of the duke's sword-hilt was heard on every stair. Greene at once went aboard his ship and refused to obey a summons from the admiral, who, it afterwards transpired, had intended to make the plucky Nantucket man an officer in the English navy. All the strategic resources of a quick, ready mind were often called into play during a |

"MANY A BRIDE STEPPED FROM HER HOME ABOARD HER HUSBAND'S WHALER." |

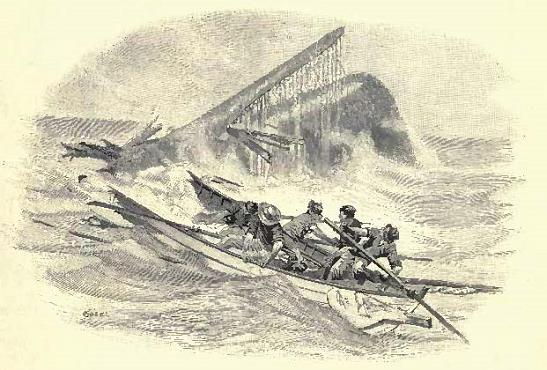

whaleman's career, not only in weathering storms and in avoiding destruction of boats and loss of life when attacking whales, but also in escaping massacre from savage islanders and in outwitting pirates. In 1819 the whaleship Syren, while on a voyage to the eastward of Cape Horn, met with an adventure which would have proved fatal to all hands but for a quick stratagem of the mate. One fine day, off one of the Pelew Islands, all the boats being after whales, and but a few men left aboard the vessel, a large band of armed natives suddenly swarmed over the bulwarks. The crew fled to the rigging, leaving the naked, howling savages in full command of the ship. The mate, on coming alongside, took in the situation at a glance, and quickly ordered the men to open the arm-chests and scatter on deck all the tacks they could find. In a moment it fairly rained tacks upon the naked savages. The deck was soon covered with these little nails. They pierced the feet of the islanders, who danced about with pain which increased with every step they took, until, with yells of rage and agony, they tumbled headlong into the sea and swam ashore. Unfortunately in the struggle the mate received an arrow-wound just over one of his eyes, and was obliged to retire from the sea. The ship Awashonks of Falmouth, Prince Coffin, master, touched October 5, 1835, at Ramarik Island, one of the Marshall group. The natives, as was customary, came on board, but not in unusual numbers. About noon, the ship's company being scattered,- three aloft on the lookout for whales, and one watch below,—the natives, who had unnoticed grouped themselves, made a sudden rush for the whaling spades and began a murderous onslaught upon all on deck, killing the captain and the first mate. The third mate escaped by jumping down the fore-hatchway. The natives, being now in possession of the deck, fastened down the hatches and closed the companionway, and the leader took the wheel and headed the ship for the shore. But the men aloft, notwithstanding the horrible butchery they had witnessed, retained sufficient presence of mind to cut the braces, and, the yards swinging freely, the ship lost her steerage-way and slowly drifted towards open water. Meanwhile those below had worked their way aft to the armory in the cabin, from which they fired with muskets whenever a savage presented a mark. The third mate now ordered a keg of powder up from the run, and a large quantity of its contents was placed on the upper step of the companionway and a train laid to the cabin. Commanding the men to rush on deck the moment of the explosion, regardless of the consequences to him, the mate fired the train. With the crash of timbers were mingled the yells of wounded and mangled savages; and the crew, rushing on deck, swept the terrified islanders overboard. The gallant third mate, Silas Jones, took charge of the ship and brought her home. A clever ruse was executed at considerable peril in April, 177 i, by two Nantucket whaling captains, Isaiah Chadwick and Obed Bunker, whose sloops were lying at anchor in the harbor of Abaco. Observing a ship off the mouth of the harbor signaling for assistance, one of the captains, with a crew composed of men from sloops, went to the stranger's aid. On boarding her the commanding -officer welcomed him by presenting a pistol to his head and ordering him to pilot the ship into the harbor. The Nantucket skipper naturally obeyed, but took care to pilot the vessel to an anchorage where a point of land lay between her and the sloops. The whale-boat was then dismissed. The skipper had noticed that all the men on the deck of the ship were armed, while one unarmed man paced the cabin. The Nantucketer, concluding from these circumstances that the ship was in the hands of pirates or mutineers, the man in the cabin being the former captain, straightway devised a plan for recapturing the vessel. An invitation to dine on one of the sloops was extended to the usurping captain. He accepted, and came aboard with the boatswain and the man who had been seen pacing the cabin, whom they introduced as a passenger. At a given signal the usurper was seized and bound, and the actual captain then explained that the crew had mutinied with the intention of becoming pirates. The Nantucketers then promised immunity to the boatswain if he would return to the ship, come back to the sloops with the former mate who was in irons, and aid in recapturing the vessel. They shrewdly intimated that a man-of-war was lying within two hours' sail, from whom they could secure the necessary aid to overpower all resistance, and agreed with him that they would set certain signals when they had obtained help from the war vessel. The boatswain, however, remained away so long that it became evident he had played false. One of the sloops then stood out boldly as if to invoke the aid of the man-of-war. As she approached the ship the mutineers shifted their guns over to the side at which they expected her to pass, and trained them so as to sink her. But the Nantucketer was too clever for them. The sloop suddenly changed her course and swept by on the opposite side before the ship's crew could reshift the guns. Then, standing on her course, she sailed out of sight. She then tacked, and, having set the |

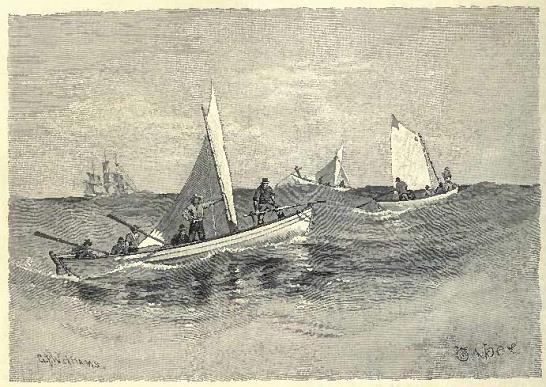

signal agreed on with the boatswain, steered straight for the corsair. When the sloop was sighted from the ship, the crew of the latter, seeing the signal, presumed there was an armed force from the man-of-war aboard the Nantucketer, and precipitately taking to their boats, they fled to the shore, where they were afterwards captured. The whalemen took possession of their prize, released the mate, and sailed the ship to New Providence, where a bounty of $2500 was awarded them. As the vessel whose boat-steerer was the first to fasten on to a whale could claim the cetacean against all comers, there was naturally great rivalry between the boats from different vessels which had simultaneously . sighted a whale as to which should be the first to fasten on; and this spirit of rivalry was fanned to fever heat when the whalers happened to be of different nationalities, for instance, American and English. About 1816 the boats of the Apollo of Martha's Vineyard, Captain Jethro Daggett, the first whaler from "the Vineyard" to round Cape Horn, were famous for "getting there" ahead of all rivals. One day the captain of an English whaler came aboard the Apollo for a "gam." In the course of conversation he asked:

"Are those the boats that beat everything in these waters?" "Look at the crew, not the boats!" was Captain Daggett's quick reply. There has been considerable discussion regarding the ship which struck the first sperm whale in the Pacific Ocean, the honor being claimed for several vessels. It is, however, possible to fix not only upon the first ship but also upon the first person that merits this distinction. Samuel Enderly, [sic, 'Enderby'] a famous London merchant of the last century, having many dealings with the whaling merchants of Nantucket, not infrequently fitted out Nantucket commanders. In 1788 he fitted out James Shields with the ship Amelia for the Brazil banks. The Amelia arriving on the whaling ground too late in the season, In June of the same year in which the Amelia |

"GAMMING." was fitted out the Penelope, of Nantucket, from Dunkirk, was whaling in the Arctic Ocean. Perhaps nothing illustrates better the daring of the American whalemen than the intrepidity with which they pushed their small vessels far into the frozen regions of the North. Over a century ago the Penelope reached a point beyond which the best equipped modem Arctic expeditions have been able to penetrate only a little more than one hundred and seventy-five miles. The following entry from the log of the Penelope records this remarkable achievement: Sunday June 22 day First fresh winds Perhaps the most thrilling narrative of the perils of Arctic whaling has come down to us from the last century; and while the facts it gives seem beyond the range of the possible, it is so minute in date and detail that to reject it altogether hardly seems justifiable. In August, 1775, runs the story, Captain Warrens, of the whaler Greenland, while becalmed among icebergs sighted a vessel with rigging dismantled. She had the appearance of having been a long time deserted. A boat was lowered and pulled for her, and Captain Warrens with part of the crew boarded her. The deck was deserted, but when they descended into the cabin a weird spectacle met their eyes. Seated at the table was the corpse of a man covered with green, damp mold. He held a pen, and before him lay a log-book this having been the last entry:

On the floor lay the corpse of a man, and a dead woman was found in one of the cabin berths. In the forepart of the vessel dead sailors were discovered, and at the foot of the gangway crouched a boy. No fuel nor provisions were found. The vessel had been frozen in thirteen years. It is difficult to give credence to this tale. But it is current in whaling circles, and old whalemen say they heard it seventy years ago from the veteran whalemen of those days. Besides the perils of the sea, which in the case of the whalemen—whose cruises often led them into waters never before vexed by the keels of civilized nations and among islands inhabited by savages—were far greater than those which encompassed the ordinary merchantmen, there were the dangers involved in their special vocation. Their huge prey often wrought as great destruction as the hurricane or the ice. Instances are on record where as soon as struck the whale has shown fight, and in turn attacked and splintered the boats about him or smashed them all with one sweep of his tail, crushing and mangling some poor fellow in his jaws. The lurid lithographs depicting scenes of this kind, which were so popular when the whaling industry was at its height, were founded upon well- authenticated instances. A number of these "whaleiana" hang in the "Captains' Room" in the Nantucket custom-house, where the old whaling captains meet to smoke and "gam"; and almost any one of these veterans can give |

the names of the vessels and boat-steerers, and even further details of the tragedies depicted in this art gallery. The Boston "News Letter" of October 2, 1766, reports a Captain Clark discovering a spermaceti whale near George's Banks. He manned his boat, and gave chase. A son of the captain was forward, ready with the lance. Suddenly the whale came up with its jaws against the bow with such violence that the captain's son was thrown a considerable distance into the air. When he fell, the whale, having turned, caught him in its jaws and made off with him. The New York "Post Boy" of October 14, 1771, gives the following curious instance. "THERE SH' BLOWS, BLOWS, BLOWS!"(RIG ON WHALING SCHOONER.) Marshall Jenkins, belonging to a vessel then recently returned to Edgartown, had a singular experience. The boat of which he was one of the crew struck a whale. It turned, bit the boat in two, took Jenkins in its mouth, and went down with him. On rising again it threw him into one part of the boat, and he was rescued with the rest of the crew. Jenkins was a fortnight recovering from his bruises. In October, 1832, the ship Hector of New Bedford raised a whale and lowered for it. The whale at once took the initiative, and struck the mate's boat, staving it badly. The captain's boat then advanced on the whale. The monster turned in an instant, seized the boat in its jaws, held it on end, and shook it to pieces. The mate then offered to lead another attack with a picked crew. But the whale again assumed the offensive, and the order was given to "Stern all!" for life. The cetacean chased the boat for about half a mile, sometimes bringing its jaws together within half a foot of it. At last the mate, who was keenly watching his chance, succeeded, as the whale became somewhat exhausted and turned to spout, in burying his lance in the monster's vitals, killing it almost instantly. On cutting it in two, harpoons belonging to the ship Barclay were found; and it was subsequently discovered that the mate of the Barclay had been killed by this whale about three months before. In 1850 Captain Cook, of the bark Parker Cook of Provincetown, lowered two boats for a bull sperm whale. The boat-steerer of the first boat got in two irons, but before the boat could be brought head on, the whale broached half way out of water and capsized the craft, the line fouling the boat-steerer's leg and almost severing it from his body. He cut the line and was picked up with the rest of the crew by the other boat, which pulled for the bark, with the whale in pursuit. The whale then attacked the vessel, striking her twice, but was killed before irreparably damaging the bark. The Ann Alexander of New Bedford was sunk by a whale August 20, 1850. The monster had smashed two boats and pursued a third to the ship, at which it then rushed, breaking a large hole through her bottom. All hands were obliged to take to the boats, but fortunately they were rescued before they were brought to the last extremities of starvation. Five months later the whale was taken by the Rebecca Simms of New Bedford, two of the Ann Alexander's harpoons being found in its carcass. Less fortunate were the survivors of the whale ship Essex, which, like the Ann Alexander, was sunk by a whale. The story of her loss and the subsequent sufferings of her crew is one of the darkest tragedies of the ocean, the leading features of which have been preserved in a diary kept by the first mate, Owen Chase, which is in the possession of F. C. Sanford of Nantucket. The ship Essex, Captain George Pollard of Nantucket, sailed August 12, 1819, on a whaling voyage. Nothing of special note occurred until November 16, in latitude r ° o' south, longitude 118° west. That afternoon, the boats being in a shoal of whales, the mate's boat was stove in by a whale and returned to the ves- |

sel for repairs; the mate's intention being to nail a piece of canvas over the hole and then to join the other boats at once. Accordingly he turned the boat over upon the quarter, and was in the act of nailing on the canvas when he observed a sperm whale, about eighty-five feet in length, lying about twenty rods off the weather bow. What followed can be best told in the mate's own words:  LANCING A WHALE.

|

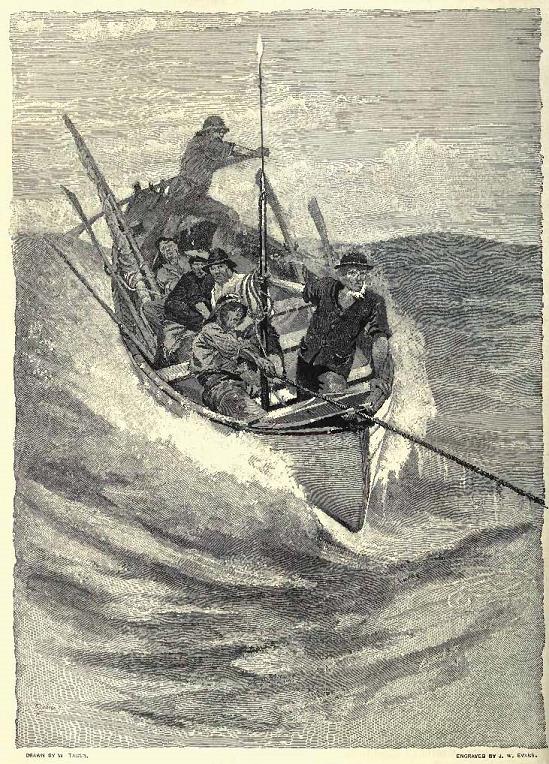

The mate cut the spare boat adrift, and had no sooner launched her than the ship fell over on her beam ends, full of water. The captain and the second mate had observed that some sudden catastrophe had befallen the ship, and their boats had now come upon the scene of the disaster. The vessel's masts were cut away and she partly righted. Precious use was made of this opportunity to secure provisions, water, and a few nautical instruments, and the gunwales of the boats were built up six inches with light cedar boards. The boats left the ship November 22, latitude 13' north, longitude 120° west, about 1000 miles from land, and shaped their course south-southeast. The allowance of food was one biscuit and half a pint of water a day per man, and about the 16th of December this was reduced one-half. The day being very hot, relief was sought by bathing in the sea, and barnacles being discovered on the bottom of the boats, these were scraped off and eagerly devoured. December 20 land was seen, and one can readily imagine the feelings with which these half-starved wretches hailed the sight. But their joy was short lived. It was Ducie's Island, barren of everything but small patches of peppergrass and a spring, which was discovered on the 22d, and of which some of the men drank so copiously as to endanger their lives. December 27 the island was abandoned by all but three of the crew, who preferred remaining there rather than to endure sufferings like those they had just passed through. The boats remained together until January 12, 1820, when they were separated by a storm. Under date of January 14 Chase makes this entry in his journal:

By January 20 they were reduced to a still more wretched condition.

As if in mockery of their starving condition, Chase dreamed that a rich repast was placed before him, and just as he was about to partake of it he awoke, all the more ravenous for his dream. February 8 they sank so low that speech and reason seemed to be impaired. One of the crew, Isaac Cole, went mad outright, hoisted the jib, cried out that he would not give up, that he would live as long as any of them, and then collapsed. At this point of their sufferings Chase suggested that Cole's body should serve as food. His companions, seeing therein the only hope of prolonging their life, agreed. "We separated his limbs from his body," writes Chase, "and cut all the flesh from the bones; after which we opened the body, took out the heart, and then closed it again, sewed it up as decently as we could, and committed it to the sea. We now first commenced to satisfy the immediate cravings of nature from the heart; after which we hung up the remainder, cut in thin strips, about the boat to dry in the sun; we made a fire and roasted some of it, to serve us during the next day." Thus they sustained life till February 15. They were then down to almost the last morsel of bread. In this extremity, at seven o'clock on the morning of February i8, there was a cry of "Sail ho!" The vessel proved to be the brig Indian of London. The men were rescued, carefully tended, and in a few days were considerably recruited. The captain's boat, the two survivors in it raving with hunger and exhaustion, was picked up in latitude 37° south, off the island of St. |

FAST TO A WHALE. |

Mary, by the whale-ship Dauphin, which reached Valparaiso the 17th of March. The second mate's boat became separated from the captain's on the 28th of January. No trace of it was ever found. Before the separation the provisions were exhausted and life was sustained by cannibalism, the flesh of three negroes who had died of exhaustion being divided between the two boats. On the 1st of February, after the mate's boat had been lost sight of, the captain and the three other men with him found themselves once more without a mouthful of food in their boat. They then deliberately drew lots to see who should die and who should be the executioner. It fell upon Owen Coffin to die and upon Charles Ramsdale to slay him. Coffin was a cousin of Captain Pollard, and the latter begged Ramsdale to kill him instead of the doomed man. But Coffin refused to allow the sacrifice. On the 11th of February Barzilla Ray died, leaving Captain Pollard and Ramsdale the only survivors. Of the crew of the mate's boat two survived besides Chase himself. Twenty all told had left the Essex in the three boats. The three men who remained on Ducie's Island were rescued by an English vessel. They too had endured terrible suffering, and when rescued were almost too weak to talk. The story of the Essex's loss and of the dire necessity to which the survivors were reduced preceded Captain Pollard to Nantucket. Eyewitnesses of the scene on his return say that the cliffs and wharves were lined with spectators and that he walked to his home through an awe-struck, silent crowd. Five months from home on his next voyage, in the Two Brothers, he ran her on a reef and she proved a total loss. He then retired from the sea and died in 1870, eighty-one years old. Owen Chase, however, was invariably fortunate on his subsequent voyages. Another tragic chapter in the history of the whaling industry was the mutiny on the Globe, Captain Thomas Worth, which cleared from Edgartown, December 15, 1822. She doubled Cape Horn about March 5, 1823, and stood to the northward. Nothing unusual occurred until nearly a year later. What then happened has been described in a journal kept by two of the crew, William Lay and Cyrus M. Hussey, a copy of which, believed to be the only one in existence, is in the possession of Mr. Sanford. Among the Globe's boat-steerers was Samuel B. Comstock. The night of January 25, 1824, Comstock had the second watch with the waist-boat's crew. The captain was asleep in a hammock suspended in the cabin because his stateroom was warm. During the watch Comstock and Silas Payne of Sag Harbor, armed respectively with an ax and a boarding-knife, entered the cabin. Comstock struck the captain with the ax, killing him instantly, and called to Payne to kill the mate with the boarding-knife. Payne made a thrust, but the mate awoke and seized Comstock by the throat, at the same time knocking the light out of the boat-steerer's hand. Comstock gasped that he had dropped the ax. Payne picked it up and handed it to the boat-steerer, who struck the mate on the head. The latter fell in the pantry and was there despatched by Comstock, while Humphreys, the negro steward, held the light. Comstock then locked the second and third mates, Lumbert and Fisher, in their staterooms, left a watch in the cabin, and went on deck to get another lamp at the binnacle and to load two muskets to which bayonets were fixed. Against Fisher he had a special grudge, as he had been thrown by the third mate a few days before in a wrestling match, and he first fired through the door in the direction of Fisher's berth. He then broke into the stateroom and made a pass at Lumbert, but, losing his footing, fell. Lumbert seized him, but he managed to free himself. Meanwhile, however, Fisher had wrested the gun from the mutineer; but on Comstock's assurance that their lives would be spared he foolishly gave it up. Comstock no sooner had the weapon in his hand than he ran Lumbert through the body and deliberately shot Fisher. The bodies of the two men were then thrown into the sea, though enough life was left in Lumbert for him to cling to the sheer plank and make efforts at swimming after he lost his hold. Comstock ordered out a boat to finish Lumbert; but no one making a move to obey, he countermanded the order. Within less than a month every one of the mutineers met a violent death. January 27 Comstock caught the negro steward, William Humphreys, loading a pistol. Questioned regarding his action, he replied that he had overheard two of the crew, Kidder and Smith, plotting to retake the ship. They denying this, a trial was ordered for the next morning. It took place before a jury of two, Comstock acting as judge. The following was his charge:

Of course the negro was found guilty. When the gallows was rigged and the noose adjusted Comstock announced that one bell would be the signal for the execution, and told Hum- |

SOUNDING. phreys he had but fourteen seconds longer to live. "Little did I think I was born to come to —" began the unhappy man, when the bell struck and he was swung off. About February 13 the vessel came to anchor off one of the Malgrave Islands, and there being no harbor, a supply of provisions was conveyed ashore on a raft constructed of spare spars. Comstock then issued the following pronunciamento, which was sealed in black by the mutineers and in blue and white by the others:

While Comstock pitched camp ashore he left the ship in charge of Payne. On the 16th of February Payne sent word to Comstock to stop making presents to the natives. The boatsteerer, however, not only continued doing so, but even went off with a party of islanders. Payne then came ashore and stationed sentinels around the camp; and the next day, when Comstock appeared, Payne and Oliver shot him, Payne afterwards despatching him with an ax. He was sewed up in canvas and buried; and, what seems perhaps as extraordinary a perversion of religious rites as was ever recorded, a chapter from the Bible was read over the grave, the ceremony ending with the discharge of a musket. The same day Payne placed the ship in charge of a crew of six. The following morning it was discovered that they had sailed away under cover of night.1 There now remained on the island Silas Payne, John Oliver, Thomas Lilliston, Rowland Coffin, Columbus Worth, Rowland Jones, Joseph Brown, Cyrus M. Hussey, and William Lay. On the 20th of February, Payne and Oliver, who had been visiting the natives, brought two women back to camp with them. One of them fled the next morning, but Oliver and Lilliston set out and recaptured and flogged her. On the 22d it was discovered that a hatchet and chisel had been stolen. A native who during the day brought back the chisel was put in irons. The next day Payne and the crew went to the village, where they found the hatchet. As they were returning with it the Indians pursued them and attacked them with stones, overtaking and killing Rowland Jones. Payne then halted and began a consultation with one of the chiefs, in the midst of which the savages with sudden whoops fell upon the crew and butchered all but Lay and Hussey, sparing these two for reasons which they were never 1 They reached Valparaiso, where they reported the mutiny and their escape. The Globe was placed in command of a Captain King, who took her to Nantucket. |

able to learn. Lilliston and Brown fell within six feet of them, and Worth was speared by an old woman. Lay and Hussey remained on the island until December 29, 1825, when they were rescued by the United States schooner Dolphin, Commander Percival. The whaling business was always more or less speculative. The returns from some famous voyages would be considered large even in these days of vast enterprises and corresponding profits. The whalemen of New London claim that The Pioneer of their city made the most profitable voyage of any American whaler. She sailed from New London, June 4, 1864, for the Davis Straits and Hudson's Bay fishery. September 18, 1865, she returned with 1391 barrels of whale oil and 22,650 pounds of bone, valued, at the current prices, at $150,060. Another remarkable voyage was that of the Envoy of New Bedford, Captain Walker. In 1847 she had been condemned and sold to be broken up. But her purchaser fitted her up, and, although the underwriters declined to insure her, sent her to sea the following year. The result of the voyage was whale oil and bone to the value of $132,450, the vessel herself being sold at San Francisco for $6000. She was fitted out at an expense of about $8000. An American whaler was the first vessel to display the Stars and Stripes in an English port. When peace was proclaimed between Great Britain and the United States in 1783 the Bedford had just returned to Nantucket from a voyage. She was immediately loaded with oil and despatched to London.

CUT IN TWO. There is a tradition that one of the Bedford's crew was a hunchback. An English tar, meeting him, struck him on the hunch and asked coarsely: "Hello, Jack! What have you got there?" "Bunker Hill, and be d——d to you," was the breezy reply. Hundreds of islands in the Pacific Ocean were discovered and charted by whalemen. Wilkes and Perry were much indebted to these hardy pioneers, and Maury was in constant communication with them while preparing his work on ocean currents. When Benjamin Franklin was in London he was questioned |

WHALERS TRYING OUT. by merchants as to the difference in time made on their westerly voyages between the Rhode Island merchantmen and those English captains sailing to New York, the average variation being somewhat like a fortnight in favor of the former. Captain Folger of Nantucket, a relative of Franklin, being then in London, the doctor consulted him. He explained that the Rhode Island captains being nearly all former whalemen, and thoroughly acquainted with the course of the Gulf Stream from having whaled for many years along the edges of it, they had learned the advantage to be gained by avoiding it; whereas the English masters stemmed it, although in a light wind the current would set them back. At Franklin's request Captain Folger made a draft of the course of the Gulf Stream, which is substantially the same as that found on the charts of the present day. The whaling industry has dwindled to insignificance, and modern appliances for killing the cetacean have robbed it of most of its perilous and romantic features. What has become of the vast fleet of vessels whose keels once vexed the waters of every known sea? |

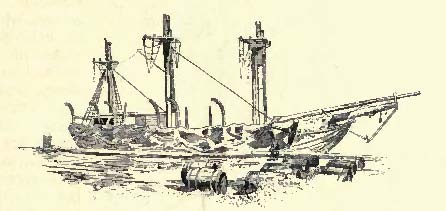

During the California gold fever hundreds of them entered the harbor of San Francisco never to set sail again; a goodly number lie with the famous "stone fleet" at the bottom of Charleston harbor; thirty-four were destroyed by the Confederate cruiser Shenandoah; and, saddest of all, many lie rotting in rows along the wharves of our old whaling ports. Such is "the end of the song." Gustav Kobbé.

WORN OUT. . . . .

|

|

Notes.

Gustav Kobbé (March 4, 1857 – July 27, 1918) was an American music critic and author, best known for his guide to the operas, The Complete Opera Book, first published (posthumously) in the United States in 1919 and the United Kingdom in 1922. Wikipedia. |

|

Source.

Gustav Kobbé.

This article may be found in the volume at Hathi Trust.

Last updated by Tom Tyler, Denver, CO, USA, December 27, 2024

|

|