|

SEAMANSHIP: |

|

|

Unlike most whalesite.org transcriptions which attemp to reproduce as accurately as possible the source document, in this instance it was decided to collect most of the many illustrations following the text of the volume. Links to the referenced figures in the illustrations should provide adequate and quick access. Tom Tyler, |

PREFACE.The Publishers, on issuing the 5th Edition of this work, which has been very carefully revised and enlarged, (some new Illustrations being also added,) hope that it may meet with the continued approval of the Officers of the Royal Navy and Mercantile Marine. Their grateful acknowledgments are due to Captain Robert Harris, R.N., who undertook the work of revision, and has executed it so ably. 15, Cockspur Street, S.W. May, 1874. |

CONTENTS.

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

ALPHABETICAL TABLE.

The following alphabet, &c, can be used under circumstances when it is not convenient to the Signal Book, and forms in itself a perfect telegraphic system, necessarily somewhat slow in its application, but having the great advantage of requiring very little previous knowledge and practice work with correctness.

All other lights in the vicinity of a Flashing Signal at night, should be concealed; signals should not be answered until thoroughly comprehended, and no signal should be commenced until the signal preceding it has been finished. |

HORARY TABLE.

Minutes are denoted by their proper figures. Thus: Hor. 2135 = 35 minutes past 11, p.m. Seconds must be made separately. |

SEAMEN'S PROVERBS.

Relating to the Hurricane Months in the West Indies.

|

LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS.

|

|

|

|

|

SEAMANSHIP.

NAMES OF THE PRINCIPAL PARTS OF A SHIP.

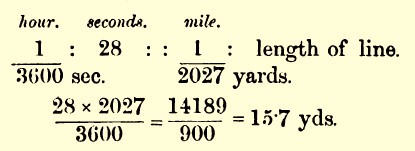

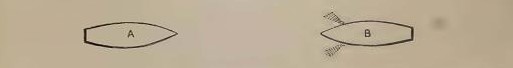

A ship is divided lengthways, into the Fore, Midship, and After parts.

Keel. – Is the principal piece of metal or timber at the lowest part of the ship, running fore and aft; it is the foundation from which all the other parts rise to form the ends and sides of the ship. Stem. – Rises from the fore part of the keel to form the bow. Stern, post. – Rises from the after part of the keel to form the stern (Fig. 1). Body post. – Rises from the keel before the stern post. The space between it and the stern post is called the screw-aperture (Fig. 1). Ribs. – A figurative expression for the framework which, resting on the keel, forms the sides of a ship. Keelson. – An internal keel, lying fore and aft above the main keel and lower pieces of the ribs confining the floors in their places. Knight heads. – Are two strong uprights, one on each side of the upper part of the stem, to strengthen the bow and support the bowsprit. False keel. – An additional keel below the main keel. By offer-ing greater resistance, it prevents the ship being driven |

so much sideways through the water away from the wind. It also protects the main keel, should the ship take the ground. Gripe. – A projection forward at the lowest part of the stem; by exposing a larger surface it prevents the foremost part of the ship, when sailing with the wind on one side, from being driven sideways away from the wind, and therefore effects the turning power of the ship. Bilge pieces. – Long pieces of wood or iron affixed to the outside of the ship's bottom, in a position to offer resistance to the water as the vessel rolls, and thereby lessen the motion. Garboard strakes. – The lowest planking outside, nearest to the keel, running fore and aft. Bends. – Are the thickest outside planking, extending from a little below the water-line up to the lower deck ports. Counter. – The afterpart of the bends, the round of the stern. Run. – The narrowing of the afterpart of the body of the ship below the water. Limbers. – Gutters formed on each side of the keelson to allow the water to pass to the pump-well. Limber boards. – Form a covering over the limbers. Double Bottom. – In some iron ships the frames and girders are covered in with iron plates, forming literally an inner ship, the space between the inner and outer ships being termed the double bottom; this method of construction gives great strength, and safety in the event of damage occurring to the outside skin. Water-tight bulkheads. – The name applied to the sides of the numerous compartments into which it is customary to divide iron vessels. Wings. – In addition to the safety afforded by the "double bottom" and "water-tight compartments," a perpendicular bulkhead is run fore and aft the centre portion of the vessel, some few feet from the side. Pump-well. – An enclosure round the mainmast and pumps. Beams. – Horizontal timbers lying across the ship, to support the decks and connect the two sides. Shelf piece. – Extends all round the ship inside for the beams to rest upon. |

Waterway. – Thick planking extending all round the inside of the ship immediately above the beams. Partners. – Frames of timber fitted into the decks to strengthen them, immediately round the masts, capstans, bitts, &c. Carlings. – Short pieces of timber, running fore and aft, connecting one beam to another, to distribute the strain of the masts, capstan, and bitts, among the several beams so connected. Knees. – Pieces of iron uniting the beams to the shelf-piece and the ship's side. Stanchions. – Pillars of metal or wood supporting a beam amid. ships. Treenails. – Wooden bolts used in fastening the planks to the timbers and beams. Caulking. – Driving oakum between the planks, it is then payed (filled in) with pitch or marine glue. The rudder. – Hangs upon the stern post by pintles and braces, for steering or directing the course of the ship (Fig. 1). Tiller. – A piece of timber or metal fitted fore and aft into the head of the rudder, by which to turn it in steering. Yoke. – A cross-piece of timber or metal fitted on the rudder head when a tiller cannot be used (Fig. 1). Wheel. – A wheel, to the axle of which the tiller or wheel ropes are connected, by which to move the rudder. Helm. – The rudder, tiller, and wheel, or all the steering arrangements of a ship. FITTINGS.

Hatchway. – An opening in the deck, forming a passage from one deck to another, and into the holds (Fig. 293). Coamings. – A raised boundary to the hatchways to keep water from going down, &c. (Fig. 293). Gratings. – An open covering for the hatchways. Scuttles. – Round holes in the ship's side for ventilation. Scuppers. – Round Holes cut through the ship's side for letting any water run overboard off the decks. Hawse Holes. – In the bows of the ship, for the cables to pass through (Fig. 293). |

Hawse Plugs. – Plugs made to fit the hawse holes, to prevent any water coming inboard. Bucklers. – Shutters fitted to confine the hawse plugs in the hawse holes, and keep them from being washed inboard. Manger. – Part of the deck partitioned off forward, to prevent any water that may enter through the hawse holes from running aft over the deck (Fig. 293). Chain-pipes. – For leading the cable through, as it passes up from one deck to another, from the chain-lockers (Fig. 275). Riding Bitts. – Timber heads fixed amidships, in the forepart of the deck, to which, with the assistance of deck-stoppers and the compressor, the cable is secured (Fig. 293). Compressor. – A large movable iron lever, fixed at the bottom of each chain-pipe; with the help of a tackle the chain is controlled or stopped as it runs out, by being nipped between the compressor and the lower part of the chain-pipe (Fig. 3). Capstan. – A barrel of wood or iron, turning round horizontally on a centre spindle: it is used, with the assistance of capstan bars, or by connection with a steam engine for weighing the anchor, lifting heavy weights, &c. (Fig. 4).

Bollard heads. – Timber heads left in the ship's side, clear of the planking, to which the anchor stoppers, hawsers, &c., are secured (Fig. 6b). Cat-heed. – A piece of timber, or an iron davit, projecting from each bow of the ship to support a bower anchor (Fig. 271). Fish davit. – A movable piece of timber, or an iron projection, for raising the fluke of an anchor and placing it on the bill board (Figs. 283, 288). Bill Board. – A ledge on the ship's side to support the fluke of the bower anchor (Fig. 295). |

Bumpkin. – A boom fixed to each bow for hauling the foretack down to (Fig. 205). Channels. – Platforms projecting outwards from the ship's side, to give a greater spread to the lower rigging (Figs. 7, 8). Dead eyes. – Used in securing the lanyards of the shrouds (Figs. 123, 122, 123). Chain plates. – Iron plates for securing the lower dead eyes to the ship's side (Fig. 7). Goose neck. – An iron outrigger to support a boom (Fig. 9). Spider. – An iron outrigger to keep a block clear of the ship's side (Fig. 10). Davits. – Outriggers projecting from the ship's side to hoist the boats up to. NAMES OF MASTS, YARDS, AND SAILS.

When a ship is propelled through the water by means of sails. Mast (Figs. 120, 121) a bowsprit, (Figs. 154, 245) and booms. – Are placed to spread the sails upon. In a vessel with three Masts they are named the fore, the main, and the mizen masts. The mainmast (Fig. 245). – Is the middle and largest mast of the three. The foremast (Fig. 245). – Is the furthest forward, and is the next in size to the mainmast. The mizenmast, – Is the aftermost and smallest mast of the three. Each mast, taken as a whole, is composed of four pieces, one above the other, each of which has its distinguishing name. The lower masts (Figs. 120, 121). – Are the lowest pieces of each mast, or those attached to the ship; they rest or step on the keelson at the bottom of the ship. In a screw steamer the screw shaft prevents any mast abaft the engines being stepped on the keelson. It is then stepped on the lower deck, which is well supported with extra stanchions. The topmasts (Figs. 120, 121). – Are the next pieces above the lower masts, and are supported by the lower trestle-trees. |

The top-gallant masts (Figs. 120, 121). – Are the next pieces above the topmasts, and are supported by the topmast trestletrees. The royal masts (Figs. 120, 121). – Are the upper pieces, and are a continuation upwards of the top-gallant masts. Thus there are three principal masts, each of which is composed of four masts. To distinguish any particular mast, one of the principal names, fore, main, or mizen, is prefixed to its other name; thus, the mast connected with the foremast are, the fore-topmast, fore-top-gallant mast, and fore-royal mast. Trysail masts. – Are small masts placed immediately abaft the lower masts; to which they are connected. The bowsprit (Fig. 154). – Projects out from the bows. The jib-boom (Fig. 154). – Is outside of, and supported by the bowsprit, by means of the heel and crupper chains. The flying jib-boom (Fig. 154). – Is outside of, and is secured to the jib-boom, the heel steps against the bowsprit cap. The sails are spread upon yards, one of which is crossed upon each mast; or upon half yards, called gaffs, on the after side of a mast; or upon stays or booms. The masts, yards, gaffs, stays, and booms, are named the same as the sails which they spread; thus, the main-sail is set upon the main-mast, and is spread by the main-yard. The main royal upon the main royal mast and yard. The spanker, upon the spanker gaff and spanker boom. The main trysail, upon the main trysail mast and gaff. The fore-topmast studding-sail, upon the fore-topmast studding-sail yard, and fore-topmast studding-sail boom. The jib is set upon the jib-boom and a stay leading from the fore topmast head to the jib-boom end, which is called the jib-stay. The flying jib is set upon the flying jib-boom, and a stay leading from the fore top-gallant mast head to the flying jib-boom end, which is called the flying jib-stay. A staysail. – Is a three-cornered sail set upon a stay, and is named after it; thus, the fore-topmost staysail is set upon the fore-topmast stay. A trysail. – Is set upon a gaff and trysail mast abaft each lower mast, but it has no boom. |

The spanker. – Is set upon a gaff, the mizen trysail mast, and boom, abaft the mizen mast (Figs. 246, 247). A fore-and-aft sail. – Is any sail not set upon a yard; that is, one set upon either a stay or gaff – such as the jibs, staysails, trysails, gaff foresail, mainsail, and the spanker. Studding-sails (Fig. 260), are sails set outside the square sails on each side of the ship, and are spread at the top upon yards, and at the bottom by booms; they are set upon each side of the foresail, fore-topsail, fore-top-gallant sail, main-topsail, and main-top-gallant sail. They are named by their respective masts; as the main-topmast studding-sail, fore-top-gallant studding-sail, &c. There are no studding-sails on the mizenmast, or on either side of the main-sail. The lower yard on the mizenmast has no sail set below it, and is named the cross jack yard. To give more support to the jib and flying jib-booms, gaffs are placed on the bowsprit to spread the rigging out in each direction and give it a larger angle. A dolphin striker. – Is thus used in connexion with the martingale (Fig. 154). Spritsail gaffs or whiskers. – In connexion with the jib guys (Fig 154). The former of these naines is derived from an obsolete sail, which was in old times set on a yard below the bowsprit. PARTS OF A MAST, BOWSPRIT; AND YARD.

Step. – The timber on which the heel or bottom of a mast or bowsprit rests. Housing. – From the heel of the mast to the upper deck, or all the part inside the ship. Hounding. – From the upper deck, up to where the rigging is placed (Fig. 120). Mast head. – From where the rigging is placed, to the top of the mast (Fig. 120). Cheeks. – The side pieces for the trestletrees to rest upon (Fig. 120). Hounds. – The flat horizontal surface of the upper part of the cheeks. |

Knees. – Projecting forward on each side of the hounds, to support the fore part of the trestletrees immediately under the topmast (Fig. 121). Trestletrees. – Two fore-and-aft pieces, one on each side of the mast, resting on the hounds, to support the rigging and the upper masts (Figs. 120, 121). Crosstrees. – Two cross pieces on top of the trestletrees, to spread the rigging of the upper ni Est (Figs. 120, 121). Top. – Rests upon the lower crosstrees and trestletrees; spreads the topmast rigging, and for the convenience of men working aloft (Figs. 120, 121, 232). Sleepers. – Two cross pieces over the top, to secure it down to the crosstrees and trestletrees. Cap. – On a masthead or bowsprit end, to support the upper mast or jib-boom in its proper position (Figs. 120, 121). Capshore. – A support under the fore part of a lower cap (Fig. 240). Wedges. – Between a mast and the partners of the deck, to keep it upright in its place. Masthead battens. – On the masthead, to protect the eyes of the rigging from being cut by the hoops (Figs. 117, 236). Bed of bowsprit. – The part of the stem on which the bowsprit rests. Bees of bowspit. – Chocks of wood on each side of the bowsprit, between the rigging and the cap, for the fore topmast stays to reeve through. Saddle of jib-boom. – A chock of wood on top of the bowsprit in side the rigging, to fix the heel of the jib-boons in, and keep it steady in its place (Fig. 160). Saddle of spanker-boom. – A support on the wizen trysail Mast for the jaws of the spanker-boom to rest upon. Jaws. – Two cleats on the inner end of a gaff or boom, fi,rining a semicircle to keep it in its place resting against the mast. Lightning conductor. – A double strip of copper on the after side of each mast, and underneath the bowsprit and jib-boom; they are connected with a copper bolt through the keel, or led along under a beam on the lower deck, through the ship's side, and down to the copper on the bottom of the ship. In ironships, with iron lower masts, the con- |

ductor of the topmasts is usually connected with the ships side by a small copper tube or pipe leading up and down the lower rigging. There is a tumbler on each cap to connect the conductors of the two masts together. The conductor on the bowsprit is carried down the stem of the ship without coming inboard. Bolsters. – Two blocks of wood, one on each side, filling up the angle between the top of the trestletree and the masthead, to prevent the rigging being cut against the outer edge of the trestletree (Fig. 116). Rubbing paunch. – A batten up and down the forepart of a lower mast, to keep the lower yard clear of the hoops when going up or down. Heel. – The lower end of a spar. Head. – The upper end of a spar. Fid-hole. – A hole in the heel of a topmast or top-gallant mast for the fid (Fig. 10b). Fid. – A bar of iron or wood put through the fid-hole of a mast, and across the trestletrees, to support a topmast or topgallant mast (Fig. 10b, 10c). The fid of a top-gallant mast is formed of two wedge-shaped pieces of wood, forced into the fid-hole from opposite sides, and then being connected together, the fid cannot be jerked out by the pitching of the ship. Yard-arm. – The ends of a yard where the rigging is placed (Figs. 130, 134). Slings. – The middle of a yard where the rigging is placed (Figs. 131, 133, 135). Quarter – Between the slings of the yard and the yard-arms (Figs. 129, 132, 134). Boom-irons. – On the jib-boom, and the lower and topsail yards, to support the flying jib-boom and the studding-sail booms. PARTS OF A SAIL.

A cloth. – A whole strip of canvas; measuring eighteen inches to two feet in breadth. Head. – The top of a sail (Fig. aa, 11). |

Leech. – The side (Fig. ab, 11). Luff. – The weather leech, or the side first touched by the wind (Fig. nk, 14). Foot. – The bottom or lower edge (Fig. bb, 11). Clews. – The two lower corners of a square sail, and the after lower corner of a fore and aft sail (Figs. k, 11, 12, 13, 14). Tack. – The foremast lower corner of a fore and aft sail; also, the rope attached to the foremost lower corner of a course (Figs. k, 13, 14). Sheets. – .The ropes which spread the lower corners of a square sail (with the exception of the courses), and the after lower corners of a course or fore and aft sail (Fig. b, 14). Peak. – The upper and aftermost corner of a spanker or trysail (Fig. a, 14). Throat or Nock. – The upper and foremost corner of a spanker or trysail (Fig. n, 14). Bunt. – All the middle cloths of a square sail. Bolt-rope. – The rope sewed round the sides of a sail. Cringles. – A strand of rope worked round and into the bolt-rope, for the reef earings, bowline bridles, and reef tackle pendants (Fig. ce, 11, 214). Robands. – Pieces of sennit plaited round the head rope of the sail, for securing it to the jackstay on the yard (Fig. 20). Head earings. – Ropes spliced into the head cringles, to secure them to the yard-arms (Fig. 248). Reef earings. – Ropes used in combination with points or beckets to secure the sail to the yard when reefs are taken in (Figs. 253, 254). Tabling. – The double part of a sail, close to the bolt-rope (Fig. h, 11). Eyelet-holes. – Holes formed in the tabling and reef-bands, for the robands, reef-lines, buntline toggles, and cringles. Bowline bridles. – Are used to flatten the surface of a sail when it is set. Buntlines. – Ropes secured to the foot of a sail, and used when taking it in or in reefing. Reeftackles. – Ropes attached to the leeches of topsails and courses, and are used in reefing (Fig. 249). |

Clewlines. – Ropes attached to the dews of all square sails, and are used when taking them in (Fig. 210). Buntline Cloth. – Double part of a sail to take the chafe of the buntline (Fig. f, 11, 12). Reeftackle patch. – Double part to take the strain of the reeftackle (Fig. p, 11). Reef bands. – Double part across a sail for working the eyelet-holes for the reef lines or points in each reef (Fig. r, 11). Belly band. – Double part across a topsail below the fourth reef for strength (Fig. 1, 11). Top lining. – Double part on the after side of a topsail, to take the chafe of the top, &c. (Fig. t, 11). Goring cloth. – Any cloth cut obliquely, as those in a jib, or the side cloths of a topsail, &c. (Fig. 13). Roach. – The curve in the foot of a sail (Fig. 12). ,Slab. – Any slack part of a sail hanging down. A square sail is roped on the after side, and a fore and aft sail on the port side; always bend a sail with the rope, between the sail and the yard or gaff. Canvas is manufactured from the finest flax, in two different breadths of 18 inches and 2 feet; and 8 thicknesses, No. 1 being the stoutest. It is made up in bolts, 40 yards long. Why has each mast so many more ropes to support it sideways and aft than it has to support it forward?

In consequence of having so few stays, it is not prudent to back a square sail (causing the wind to blow against the foremost side of it) when blowing hard. Why should not masts be supported sideways only by shrouds?

Why should not masts be supported sideways only by backstays?

Why are there no studding sails on the mizen/mast or on each side of the mainsail?

|

THE STANDING RIGGING.

To steady and secure a spar, it must have at least three separate supports. A rope supporting any mast from forward is called a stay (Fig. 245). ;Shrouds. – Are the side supports which go from the top or head of a mast to some place in a line with the bottom or foot (Fig. 121). Swifter's backstays. – Are those going from the head of any of the upper masts down to the sides of the ship (Fig. 121). Guys. – Are the side supports of a boom. The bowsprit is supported downwards by bobstays (Fig. 154), and sideways by shrouds. The jib-boom is supported downwards by a martingale (Fig. 154) and sideways by jib-guys. The flying jib-boom is supported downwards by a flying martingale (Fig. 157), and sideways by flying guys.(Fig. 154). Each stay, shroud, backstay, and guy, has the same name as the spar which it supports; thus, those supporting the main- |

top-gallant mast are, the main-top-gallant stay, main-top-gallant shrouds, and main-top-gallant backstays. Gammonings of the bowsprit (Figs. 154, 157). – Two chain lashings to secure the bowsprit down in its bed. Futtock shrouds (Figs. 120, 121). – Chain or rope shrouds, connecting the topmast rigging to the necklaces on the lower mast. Lanyards of rigging (Figs. 123, 124). – A smaller rope, used for securing the end of any part of the rigging. Masthead pendants (Fig. 120). – Short pieces of rigging hanging from the lower mast-heads; they are used in combination with tackles to get the mast into its right position (staying the mast), and for setting up the lower rigging, &c. Burton pendants (Fig. 120). – Hang from the topmast head for setting up the topmast rigging. Ratlines (Fig. 204). – Small ropes hitched across the shrouds to form ladders. Catch Ratlines. – All the ratlines are seized to the after shroud but one, except every fifth ratline, which is seized to the after shroud, and is called a catch ratline. Back ropes. – Continuations of the jib-martingale from the dolphin striker to the ship's side (Fig. 154). Jumper } Continuations of the jib guys from the spritsail gaffs to the ship's side. After jib guy }Heel chain (Fig. 160). – A chain led from the bowsprit cap round the heel of the jib-boom to keep it out in its place. Crupper chain (Fig. 160). – A chain passed round the bowsprit and the heel of the jib-boom to secure the latter down in its saddle. Jackstay (Fig. 134). – A rope stretched along the top of a yard, for the sail to be bent to. Footrope (Fig. 134). – A rope hanging under a yard, or boom, for the men to stand upon. Stirrups (Fig. 134). – Short pieces of rope hanging from the lower and topsail yards to support the footropes. Flemish horses (Fig. 132). – A short footrope hanging under the yardarms of the lower and topsail yards. Parral (Figs. 131, 133, 138, 140). – A rope to secure the topsail, top-gallant and royal yards to their respective masts. |

Truss (Figs. 135, 142, 143). – A working parral, to secure a lower yard to its mast. Slings of a yard (Figs. 135, 153). – A chain, or rope, supporting the centre of a yard. BENDS AND HITCHES.

|

An inside clinch is the most secure; an outside clinch depends alone on the seizings and is only used where an inside clinch would be liable to jamb. LEAD LINE.

A lead line is used for ascertaining the depth of water. The lead is usually hove forward from the main chains, and the soundings are taken as the ship passes the spot where it entered the water. The lead is from 7 to 14 1bs. weight ( Fig. 51), and the line from 20 to 25 fathoms long. The measurement commences at the bottom of the line, which is marked with,

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

In calling the soundings, if the depth of water alongside corresponds with any mark, the landsman calls "by the mark. 5 or 7, &c.;" if he judges that the depth corresponds with a deep, "by the deep 8 or 9, &c.;" if 1/4 a fathom more than a mark or deep, "and a quarter 7 or 8, &c." or "and a half 7 or 8, &c.;" if 1/4 of a fathom less, a quarter less 7 or 8, &c. A deep sea lead line.– Is from 100 to 200 fathoms long, with a lead weighing from 28 to 30 pounds. It is marked the same as a hand lead line up to 20 fathoms, then with one knot at 23 fathoms, three knots at 30, one knot at 33, four knots at 40, and so on to 95. Then at 100 fathoms a piece of bunting, at 105 one knot, at 110 a piece of leather, at 115 one knot, at 120 two knots, and so on, as in first 100 fathoms. The bottom of the lead is hollowed, for the purpose of being armed (filled with tallow) to ascertain the nature of the ground. In sounding with the deep sea lead, the ship is "hove to;" the lead line is carried forward on the weather side, outside everything, from the quarter to the cathead or bumpkin where it is bent to the lead; a number of men are stationed to hold the line clear of the ship's side, and to take the sounding, in case the lead reaches the bottom sooner than is expected; they each have a small coil of the line in their hands, so as not to check the lead as it is going down. The quantity of line to be hauled off the reel and passed forward depends upon the supposed depth of water. The lead is hove overboard forward, and as each man attending the line feels it tauten, and is sure the lead has not reached the bottom, he flings his coil overboard, passing the word to the next man aft, by saying, "Watch there, watch." If it has not reached the bottom before, the sounding is taken by the quartermaster, on the weather quarter, with the line as nearly up and down as possible. The most correct soundings are taken by sounding machines, of which there are several varieties, "Massey's" being usually supplied to H. M. ships. If "Burt's" bag and nipper is on the line when sounding, it acts as a check on the depth indicated by the machine (Fig. 52). | |||||||||

The register wheels are first set at the starting points, the small one at the 10 fathom mark, and the large one on the opposite side at the 150 fathom mark; the shield or catch is then shut down on the fan, the lead is hove overboard forward as before; on the lead entering the water, the action of the water lifts the catch up and turns the fan, which motion is communicated to the register wheels. Immediately the lead reaches the bottom, the fan ceases to revolve, and on the line being hauled in, the action of the water presses the catch down on the fan and locks it in its position. The depth of the water in fathoms is shown by the register wheels. LOG LINE.

A log line is used to ascertain the velocity of a ship through the water. The log-ship, a piece of wood in the shape of a sector of a circle, with the arc weighted, and fitted with two lines to enable it to swim square and upright in the water (Fig. 53), is fastened to the end of the line. One of the lines is fitted with a peg to draw out. On the log-ship being thrown overboard, it catches the water and remains stationary, and as the ship moves ahead away from it, the line is pulled off the reel; a sufficient quantity of stray line is allowed to run away to enable the log-ship to get proper hold of the water before the measurement begins; a piece of white bunting is placed to mark the end of the stray line, and the commencement of the knots. The length of each knot must be the same part of a sea-mile as the sand-glass is of an hour. It is usually calculated to correspond with a glass running 28 seconds. If the ship is going very fast through the water, a 14-second glass is used, when the distance shown on the log-line must be doubled. The line is marked with

|

TO HEAVE THE LOG.

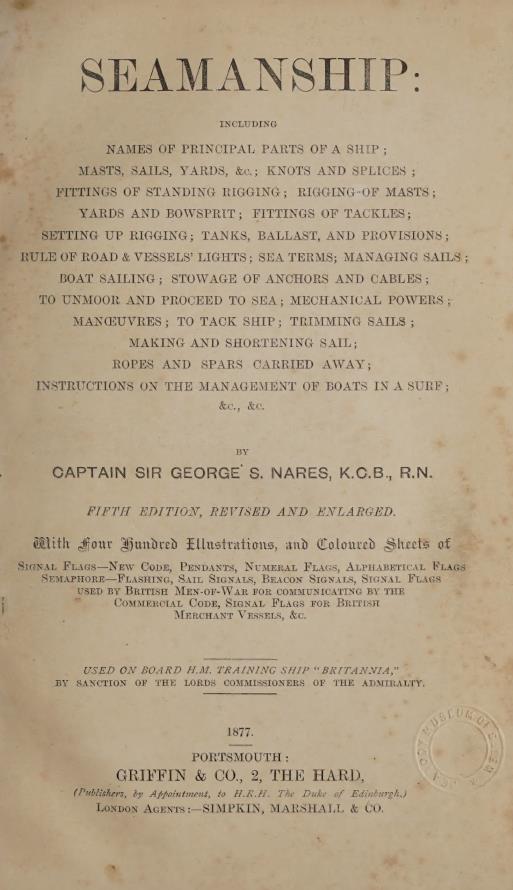

The glass is first ascertained to be clear; the log-ship, and sufficient line to enable it to fall clear into the water, is then hove over the lee quarter; the line is allowed to run off the reel, with an occasional help, so as not to allow the log-ship to be pulled through the water after the ship; when the piece of white bunting at the end of the stray line passes over the quarter, " turn" the glass; when the glass has run out, " stop;" the line is checked, and the nearest marks will show the velocity of the ship per hour in knots. The pressure of the water on the log-ship then causes the peg fitted to one of the lines (Fig. 54) to come out, when the log-line is easily hauled on board. To calculate the length of a knot on the log-line: –

The most correct way to ascertain the distance run by a ship is by means of a patent log. "Massey's" is the patent log usually seen in H. M. Navy (Fig. 55). A towing line is used sufficiently long to take the log clear of the eddy in the wake of the ship. See the register wheels set at the starting points, which are respectively 1, 10, and 100. Tow the log overboard from the weather quarter. As the ship tows the log, the fan is turned by the action of the water, which motion is communicated to the wheel work by means of the connecting cord. When the log is hauled on board, the distance run is read off from the register wheels. There are 1760 yards in a land mile, and 2027 in a sea mile or knot; why is there any difference? A land mile is measured without any reference to the size of the earth. |

A. sea mile is the number of yards contained in the circumference of the earth at the equator, divided by 21,600 (360° x 60), the number of minutes in a circle, or the sixtieth part of a degree on the equator.

FIRST PART – RUNNING RIGGING.

Halliards. – Are used to hoist a sail on its respective mast or stay, they are led from the sail to the mast-head. Sheets. – Are used t o spread the foot of a sail. In a square sail, they lead down from the clews to the yard-arms imme-diately below them. In a course, they lead from the after-clew down to the ship's–side. In a jib or staysail, the after-clew has two sheets, one leading to each side of the ship. Tacks. – Are used to confine the foremost clew of a course, they lead from the clews of the foresail to the bumpkins, and from the clews of the mainsail to the maintack cavil in each waist. The courses have a tack and sheet secured to each clew, the tack is always used on the weather side, and the sheet on the lee side of the ship. Braces. – If the wind was always blowing exactly aft, the yards might be fixed at right angles to the ship; but when the wind is blowing against the side, the sails and yards must be braced up to allow the wind to strike them at a larger angle. Braces are therefore used to move the yards horizontally into the required position. A square sail being secured at the two bottom corners, to the yard immediately below it, evidently brings a great strain on the yard-arms, bowing them forward and upwards – in order to support them, the braces are led, if possible, from the yard-arms, aft and downwards. Lifts. – -Are used to support the yard-arms. They lead from the yard-arms up to the mast-head. Clewlines. – In taking in a square sail, a clewline is used to pull each clew up to the quarter of its own yard. Clewgarnets. – In taking in a course, a clewgarnet is used to pull each clew up to the quarter of its own yard. Buntlines. – In taking in a square sail, buntlines are used to -pull the foot of the sail up to or a little above the yard. |

Leechlines. – In taking in a course, leechlines are used to pull the leech of the sail up to the yard on the foremost side. Slablines. – After a course is taken in, slablines are used to confine the slack sail which would otherwise hang down below the yard. Reeftackles. – Are used to haul the leech of the sail taut up to the yard-arms in reefing, and thus lighten the sail for the men on the yard. Bowlines. – After a sail is hoisted and the yard braced up, the bowline is used to drag the weather-leech further forward, thus tautening the luff, and flattening the surface of the sail as much as possible. Brails. – Are used in taking in a spanker or trysail, they lead from the after-leech of the sail up to the gaff or trysail mast on both sides. Vangs. – Are for steadying a gaff when the sail is brailed up. Downhauls. – Are for hauling down a jib or staysail. Outhaul. – Is used to haul the spanker out to the end of the boom, and sometimes to haul a trysail out to the end of the gaff. In running rigging, all single ropes are secured to the yard or sail that is to be moved, led through a sheave or a block secured at the place towards which it is required to move it, and then down on deck. To gain more power, or to lighten the strain on a rope, it is doubled, trebled, and sometimes rove IN ith four or more parts. To double a rope. – Cast off the standing part from the yard or sail, secure a block in its place, reeve the rope through it, and make fast the standing part close to the block already secured at the place towards which it is required to move the yard or sail. With any odd number of parts of rope in a purchase, the standing part is secured to the yard or sail. With an even number the standing part is secured at the place towards which the yard or sail is to be moved. As the strop of a block is only supposed to bear the strain of a rope rove through it, the standing part, should, if possible, be secured to a separate place. |

ROPES USED IN SETTING AND TAKING IN SAILS.

In setting. Courses – let go the slablines, leechlines, buntlines and clew- garnets – haul upon the weather tack and lee sheet. Topsails – let go the buntlines and clewlines – haul upon the sheets and halliards. Top-gallant sails – let go the buntline and clewlines – haul upon the sheets and halliards. Royals – let go the clewlines – haul upon the sheets and halliards. Jib – let go the downhaul – haul upon the halliards and sheets. Spanker – let go the brails – haul upon the outhaul. In taking in – Courses – let go the weather tack and lee sheet – haul upon the clewgarnets, buntlines, leechlines, and slablines. Topsails – let go the sheets and halliards – haul upon the clew-lines and buntlines. Top-gallant sails – let go the sheets and halliards – haul upon the clewlines and buntline. Royals – let go the sheets and halliards – haul upon the clewlines. Jib – let go the halliards and sheet – haul upon the downhaul. Spanker – let go the outhaul – haul upon the brails. Note. – Braces, lifts, bowlines, and vangs have not been mentioned. KNOTS AND SPLICES.

Eye splice (Figs. 56, 57, 58, 59, 60, 61). – For the eye of all single ropes. Short splice (Figs. 62, 63). – For joining two ropes, stropping blocks, &c. Long splice (Fig. 64). – For splicing running rigging. Grummet (Fig. 65). – A neat strop for blocks, &c. Wall knot (Fig. 66). – Finishing off seizings; forming a shroud knot, &c. |

Shroud knot (Fig. 67). – Knotting shrouds, &c. Stopper knot (Figs. 68, 69). – Deck stoppers. Matthew Walker (Figs. 70, 71). – For securing the standing part of a rope, &c. Selvagee strop (Fig. 72). – Is not so liable to slip as a common strop. Standing Turk's-head (Fig. 73). – On the footropes of jib-boom, &c. Flemish eye (Figs. 74, 75). – For the lashing eyes of stays. SEIZINGS, LASHINGS, &c.

Flat seizing (Fig. 76). – A light seizing. Throat seizing (Figs. 77, 78, 79, 80, 81). – For block strops, and seizing rigging where the strain comes on both parts of the rope. Racking seizing (Figs. 82, 83). – Seizing wire rigging, or where the strain is only on one part of the rope. Rose lashing (Figs. 84, 85). – Lashing the eyes of all rigging, &c. A rose seizing is used to secure rigging with a single eye, flat on a spar; such as the inner ends of the foot ropes on upper yards (Fig. 85). Form a half crown (Fig. 98). – Fitting backropes, &c. Whip a rope (Fig. 86). To preserve the end of a rope. Point a rope (Fig. 86b). Marl down (Fig. 75). – To prepare the ends of a splice before serving. Make a fox. – For making gaskets, mats, rackings, temporary seizings, &c. Make a nettle. – For hammock clews, seizings, &c. French sennet. – For furling gaskets. Paunch mat }. Sword mat. } For chafing mats. Worm (Fig. 87). Parcel (Fig. 88). To preserve a rope from wet or a chafe. Serve (Fig. 89). Spanish windlass (Fig. 90). – A purchase for heaving two ropes together. |

Studding sail halliard strop (Figs. 91, 92). – For bending studding sail halliards to the yard. In stropping blocks, with a thimble once and a half the round of the block will allow rope enough for the strop if single. For double strops take twice the round of block thimble and rope, and allow end for splicing. In stropping with a grummet, the strand should measure four and a half times the round of the block. Before passing a seizing over a rope that has been served, a strip of tarred canvas is put on, to keep the turns of the seizing from opening the service. All ropes are parcelled with the lay. The lowest part of the rope is parcelled first, and work up, like tiling a house, so that the wet may run down without getting between the parts of the parcelling. All ropes are served against the lay, as the service lies much closer. TO SPLICE AN EYE IN A THREE-STRANDED RIGHT-HANDED ROPE.

Bend the end of the rope down, having first opened the strands (as in Fig. 56), leaving the middle strand on top of the rope. The middle strand is forced under any convenient strand in the rope (according to the size of the eye required), from right to left (as in Fig. 57). The left-hand strand is then forced from right to left, over one strand and under the next on the left (as in Fig. 58). Now turn the rope round to the left, so as to bring the remaining or right-hand strand on top of all (as in Fig. 59). The right-hand strand is then forced from right to left under the strand of the rope immediately on the right of the one the first or middle strand was placed under (as in Fig. 60). In placing this strand, if a half turn is taken out of it, it will lay closer. In completing the splice it is immaterial which strand is used first, as each is taken over one strand of the rope, and under the next one. |

In large ropes each strand is halved before being spliced in to form the second layer. In a left-handed rope the strands are put in from left to right. TO SPLICE AN EYE IN A HEMP OR WIRE ROPE

WITH MORE THAN THREE STRANDS. The second strand from the left is forced from right to left under any convenient strand, as in Figs. 57 and 61. The left-hand strand is then forced under the same strand, and also under the next one on the left, thus laying under two strands, then turn the rope over as in Fig. 59 – work each of the remaining strands in as the right-hand strand of the three-stranded rope (Fig. 60), working round towards the handis then halved the right – each strand and splice finished as before. With a five-stranded rope, the centre strand of the five is forced under the most convenient strand, then the next strand on the left under one, and the left-hand strand of all under two strands, as in Fig. 61, then the two right-hand strands before. In splicing wire-rope, as soon as one layer is finished, a temporary seizing of spun yarn must be put round everything before dividing the strands, ready for the next layer. Each strand is put in three times, in order to taper the splice down better. ROPE MAKING.

|

Why has a four-stranded rope a heart in the centre? To make the strands lie evenly: if there were no heart, the rope would have a hollow in the centre. The greater | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

number of strands a rope has, the larger will be the hollow, and consequently the heart. Why is gun gear laid up left handed? The yarns being spun right handed, and the strands being also laid up right handed, make the rope much softer and more pliable, but it has the disadvantage of being more liable to soak up wet. FITTINGS OF THE STANDING RIGGING.

The simplest way to make fast a rope to support a spar, is by splicing an eye in the end of the rope, and placing it over the spar. fork and lashing eyes (Fig. 94).

(A fork with lashing eyes is the same as an eye splice with the centre cut and the two parts lashed together again). cut splice (Fig. 95).

If two ropes, one on each side of a spar, are fitted with eye splices, there will be two ropes round the mast head. By splicing each rope into the other to form a cut splice, there will be only one; but this fitting is not good, and must not be used for any of the principal ropes, on account of the strain which is brought on the back of the opposite splice. throat seizing on the bight (Fig. 96).

When there are a number of ropes supporting a spar, as many as possible are fitted in pairs; the middle or bight of the rope is placed over the. end of the spar, and a seizing is put on to form an eye. |

Thus, with an even number of ropes, they are all fitted in pairs with throat seizings on the bight. With an odd number, they are all fitted, in the same way except the odd one, which being a single rope, is fitted with an eye splice. horse shoe (Fig. 97).

Immediately that a rope is bent it becomes weaker, therefore all rigging should be kept as straight as possible. In some cases, the two legs of a pair of shrouds, &c. are required to be taken well apart from each other. If fitted with a throat seizing on the bight round the mast head, too much strain would be brought on the seizing, besides betiding the rope. Therefore a short piece of rope is spliced into each leg, to act instead of a seizing, forming a horse-shoe splice. half crown (Fig. 98).

Another way of fitting rigging, when the legs are spread well apart, is by crossing the . ends, and seizing them at the cross, to form an eye. All the standing rigging is parcelled and served over wherever it is liable to be chafed, where wet is likely to lodge, or where any of the strands have been opened for splicing (Figs. 88, 89, 89b). The parcelling would not lie smooth on a large rope, unless the hollows between the strands were first filled up with worming (Figs. 87, 89). Example: – All the large shrouds are wormed, parcelled, and served, where they touch the masthead, to preserve them from the wet; and one-third of the way down each leg, to protect it from the chafe of the other ropes, and from the yards when braced sharp up. FITTINGS OF BLOCK STROPS.

A single strop (Figs. 99, 100,) is a ring of rope or chain. A doable strop (Figs. 105, 106,) is a long single strop doubled. |

A single strop is the one generally used. A double strop, or two single strops, are used with large blocks when a block is required to lie differently, or when greater strength is required. if fitted round a spar.

How must a block be stropped if the rope is required to be led in a line with or along the spar? With a single strop (Figs. 99, 100); or, if a large rope, two single strops (Figs. 109, 110). How must a block be stropped if the rope is required to be led at right angles to the spar? With a double strop (Figs. 105, 106). if lashed on a spar.

How must a block be stropped if the rope is required to be led in a line with or along the spar? With a single strop (Figs. 101, 102); or, if a large rope, with a double strop (Figs. 103, 104). How must a block be stropped if the rope is required to be led at right angles to the spar? With two single strops (Figs. 107, 108). PLACING THE STANDING RIGGING.

The rigging forming the largest angle with the spar is put on first, and that forming the smallest angle last, thus assisting to keep the other rigging in its place. The wood-cut represents the rigging of the dolphin striker, the lowest rope evidently keeping the upper one from slipping off (Fig. 112). The only exceptions to this rule are the lower, topmast, and jib stays; these being lashed at the masthead, are placed on top of the other rigging. |

If lashings were placed below rigging, they would be cut in the rolling of the ship, as they cannot be protected with serving, parcelling, &c. EXAMPLES OF FITTED RIGGING.

Rigging fitted with an eye-splice (Fig. 93). Eyes of royal, top-gallant, and flying-jib stays (Figs. 113, 114). Eyes of all single shrouds and backstays (Figs. 115, 117). Both ends of the jib-guys and martingale (Figs. 168, 169). Flying jib-guys and martingale (Fig. 167). Topping lift for spritsail gaff (Fig. 170). All single braces and lifts (Fig. 130). All jackstays, stirrups, and flemish horses (Figs. 133, 135, 136). Foot ropes on all yards (Figs. 133, 135, 136). Yard tackle pendants (Figs. 134, 136). All single strops with lashing eyes (Figs. 101, 102). Rigging fitted with a fork and two lashing eyes (Fig. 94). All lower and topmast stays, and the jib-stay (Figs. 115, 117). Rigging fitted with a throat seizing on the bight (Fig. 96). All double shrouds and backstays (Figs. 113, 114, 115, 117). Fore and main mast-head pendants (Fig. 117). Rigging fitted with a cut splice (Fig. 95). Burton pendants; mizen mast-head pendants (Fig. 116). Jib and flying jib foot ropes (Figs. 167, 168). Rigging fitted with a half crown (Fig. 98). Jib sheet, and stay-sail pendants (Figs. 222, 223). Back ropes (Fig. 169). Rigging fitted with a horse shoe splice (Fig. 97). The jumper and after jib-guy (Fig. 170). Parts of rigging where a single strop is used (Figs. 99, 100, 101, 102). |

All lift blocks (Figs. 134, 136). All dog strops for braces (Fig. 136). Royal and top-gallant parcels (Figs. 138, 139). Chain truss strops (Fig. 135). Quarter blocks on royal, top-gallant, and topsail yards (Figs. 131, 133) All rolling tackle, and quarter strops; clewgarnet blocks (Figs. 131, 134, 135). Bobstay, and bowsprit shroud collars (Figs. 161, 163). Bobstays, (Fig. 161). Fore stay collars (if fitted bale sling fashion) (Fig. 164). Parts of rigging where a double strop is used (Figs. 103, 104, 105, 106). The jeer blocks at the lower mast-heads. All lower brace blocks (Fig. 148). Quarter blocks on lower yards (Fig. 135). Fore stay collars (if not fitted bale sling fashion) (Fig. 166). Lower fish block (Fig. 228). Parts of rigging where two single strops are used (Figs. 107, 108, 109, 110). Jeer blocks on lower yards (Fig. 135). Topsail brace blocks (Fig. 147). Upper fish block (Fig. 283). RIGGING OF MASTS.

The rigging of a royal mast, top-gallant mast and topmast, is placed upon a copper funnel fitting the mast head; this keeps the rigging together in its place when the masts are sent down, and likewise prevents the rigging cutting into the mast head. How is a royal funnel or mast rigged? With a stay leading forward, and backstays on each side (Fig. 113). How is a top-gallant funnel rigged? With a stay leading forward, and shrouds and backstays on each side (Fig. 114). |

How are the royal, top-gallant, and flying jib stays, fitted? With an eye spliced round the funnels on the royal and topgallant mast-heads. How are the royal backstays, and the top-gallant shrouds and back-stays fitted? Each pair, with a throat-seizing on the bight round the funnels on the royal and top-gallant mast-heads (Figs. 113, 114). What extra rigging is there on the fore top-gallant masthead? The flying jib-stay. It is fitted with an eye splice, and is placed immediately above the top-gallant stay, underneath the "shrouds and backstays (Fig. 114). How, and where, is the top-gallant rigging secured? The two shrouds, after leading down through the horns of the topmast crosstrees, and the rollers on the spider hoop on the topmast head (Figs. 119, 120), are spliced or toggled together, and the double block of a purchase fitted in the bight: the lower block is secured to the eye of one of the lower shrouds (Fig. 120). This ensures both the top-gallant shrouds being always taut alike, or after leading through the horns of the crosstrees they are led across, and are secured on the opposite side of the top, without using a spider hoop: Where is the fore royal stay secured? It is rove over a dumb sheave in the flying jib boom end, through the dolphin striker below the rigging, and set up to one of the knight heads. Where are the main and mizen royal stays secured? They are rove through a sheave in the topmast crosstrees amidships, and set up in the top to the eye of the upper lower shroud (Fig. 126). Where are the jib and flying-jib stays secured? They are rove through a sheave in the end of their booms, through the dolphin striker, and set up with a purchase to the knight heads, one on each side. Where is the fore top-gallant stay secured? It is rove over a dumb sheave in the jib-boom end, through |

the dolphin striker below the rigging, and set up to one of the knight heads. Where are the main and mizen top-gallant stays secured? They are led forward, rove through a hole in the lower cap, and set up in the top to the eye of the upper lower shroud (Fig. 126). (When staysails are to be set, the main top-gallant stay is taken to the fore topmast crosstrees, and the royal stay to a strop at the fore top-gallant mast-head. ) How is a topmast funnel rigged? With a burton pendant, shrouds and backstays on each side, and two stays leading forward (Fig. 115). A chain necklace is placed on the fore and main topmast under all the rigging and the bolsters for the hanging blocks to shackle to (Fig. 116). The mizen topmast if it has only one topsail tye, has no hanging blocks or necklace, the tye being rove through a sheave in the mast. What is the use of the necklace on the topmast head, and how is it fitted? It goes round the mast-head immediately on top of the trestle-trees and crosstrees, being fixed down to the latter with iron staples. The hanging blocks used in hoisting the topsail jib, and fore-topmast staysail, and sometimes for the jib stay, are iron stropped and shackled to chain or iron legs, which hang down from the necklace on each side of the masthead (Fig. 116). How, are the burton pendants fitted? With a cut splice, leaving one leg hanging down on each side of the topmast (Fig. 95). They are used for setting up the topmast rigging, &c. What difference is there in the fittings of the first and second pair of topmast shrouds? The foremost pair has a sister block seized in between them for the topsail lift and reef tackle (Fig. 116). In rigging a mast, which is the odd shroud? The after one. Which is the odd backstay? The foremost one, as it sets up well forward by itself for a breast backstay, the other two being close together aft. |

What extra rigging is there on the fore-topmast? The jib stay. The two legs of the fork are rove from for-ward down through the fork of the topmast stays, and are lashed together abaft the masthead under them (Fig. 115). It would be placed above the topmast stays, and led straight to the jib-boom if there were room for it between them and the under part of the foremost cross-tree. What extra rigging is there on a mizen topmast? A short pendant with a thimble spliced into the end, hangs down on each side of the masthead, for the standing part of the main topsail brace to reeve through, as it passes up from the mizen-chains. They are fitted with a cut-splice, and are placed on the masthead before the burton pendants. (A chain necklace and hanging blocks are sometimes used.)

How, and where, is the topmast rigging secured? With dead eyes and lanyards to the futtock shrouds, which, after reeving through the top, are secured alternately to the two necklaces round the lower mast (Figs. 120, 121). What is the use of having two necklaces? If one carries away, only half of the rigging on each side is gone. Where are the fore-topmast stays secured? They are rove through the bees of the bowsprit, through the spritsail gaffs, and set up to the knight heads with lanyards. Where are the main-topmast stays secured?</p> They are rove through iron-bound clump blocks, shackled to hoops on the head of the foremast (Fig. 128), and set up abaft the foremast with lanyards, to bolts in the deck. Where is the mizen-topmast stay secured? A strop with a thimble seized in it is placed on the main masthead, under the eyes of the lower rigging. The stay is set up with a lanyard to the thimble, or it is rove through the thimble, and secured with a racking seizing to its own part (Fig. 118). |

How are the lower masts rigged? With masthead pendants and shrouds on each side, two stays leading forward, and a jeer-block strop (Fig. 117). Note. – Except the mizenmast which has only one stay, and no jeer block strop. How are the masthead pendants fitted? With a throat-seizing on the bight round the lower masthead, leaving a long and a short leg hanging down on each side of the lower mast, the long leg being aft and the short one forward. The mizenmast has only one pendant on each side, which is fitted with a cut-splice round the mast-head. (A chain necklace round the mast-head under the bolster, with the pendants shackled to it, is sometimes used.)

What are the masthead pendants used for? The two long legs lashed together abaft the mast, are sometimes used for staying the mast (Fig. 96); the short legs for setting up the lower rigging, fishing the anchor, &c.; they are fitted short enough to admit of being dipped round the futtock shrouds. How are the burton pendants fitted? With a cut splice, leaving one leg hanging down on each side of the topmast (Fig. 95). They are used for setting up the topmast rigging, &c. How is each pair of shrouds fitted? With a throat-seizing on the bight round the mast-head. How is the after-swifter or a single shroud fitted? With an eye spliced round the mast head. How, and in what order, are the shrouds placed on the topmast or lower mast-heads? The foremost pair on the starboard side is placed first, then the foremost pair on the port side, then the second pair on the starboard side, second pair port side, and so on, working aft (Fig. 117). The seizing of the first pair of shrouds on each side, is placed as far forward on the trestletree as possible, the seizing of the second pair overlaps half of the seizing of the first pair, that of the third pair overlaps half of the second pair, and so on. With |

wire rigging, there will be room for the shrouds, if the seizings are laid clear of each other. (It is a common practice to place the after-swifters first, in order to steady the mast at once, and get it into its place whilst placing the other rigging, but it is of no use afterwards, and has its disadvantages; it raises the foremost shrouds, and therefore prevents the lower yard being braced up as sharp as by the old method. ) How are the jib, topmast, and lower stays fitted at the mast-heads? With a fork and two lashing-eyes, which are lashed together abaft the mast-head, with a rose lashing (Figs. 115, 117). If the topmast and lower stays were not fitted separately but with throat-seizings on the bight, if one stay were carried away, the strain of the mast would be on the seizing. If shot or carried away above the seizing, both stays would be gone. The seizing would likewise have to be put on aloft after the stays were placed. The jib-stay is frequently rove through a hanging block, shackled to the chain necklace at the fore-topmast head, and the end secured with a chain slip at the jib-boom end. It is set up with a purchase abaft the foremast. What is the use of the jeer block at the lower mast-head, and how is it fitted? It is used in sending the lower yard up or down, and is fitted with a long double strop. The two parts are rove up through a hole in the top before the foremost cross-tree, and lashed together abaft the mast-head with a rose lashing. Why are the stays on the lower and topmast heads placed on top of the rest of the rigging? By placing the stays on top of the rest of the rigging, it takes up less room on the mast-head, and allows the yard to brace up sharper. Note. – For the same reason the mizen stay is sometimes taken over the foremost crosstree.

What extra rigging is there on the main-mast? A strop with a thimble seized in, for the mizen topmast-stay to secure to, is placed under the shrouds (Fig. 118). How, and where, is the lower rigging secured? With dead eyes and lanyards to the chain plates, which are bolted to the ship's side (Figs. 120, 121). Notches are |

cut in the outside edge of the channel, to receive the chain plates, which are confined in their places by the guard board (Figs. 7, 8). How is a dead eye turned in, or secured to a shroud? The shroud is taken down the fore side, and round the dead eye; the end then nips round the standing part of the shroud, passing from out, in, towards the ship – throat, quarter and end seizings are put on the two parts: this leaves the seizings aft, and the ends inside in the shrouds on both sides of the ship (Fig. 123). Wooden dead eyes are in many ships replaced by iron ones, in which case the end of the shroud is taken round the shell of the dead eye and then seized up to its own part (Fig. 122). (A racking seizing, Fig. 124, has lately been used for turning in a dead eye. It is evidently the proper seizing for the purpose, and must be used for wire rigging). Where is the standing part of the lanyard of a shroud secured? For the lower rigging it is spliced into a bolt in the chains, abaft and inside of the dead eye (Fig. 123). For the topmast rigging, a Matthew Walker knot is made in the standing part, and the lanyard then rove from in, out, through the after hole of the upper dead eye (Fig. 199). Why is the standing part of the lanyard rove first through the after hole of the dead eye? On hauling taut the lanyard, the part nearest the purchase will evidently take the strain first, this part must therefore be forward immediately under the shroud, or the dead eye would be turned round. After setting up the rigging, how is the end of the lanyard secured? It is rove out over the top of the upper dead eye, taken forward round the shroud below the nip, then aft inside of everything, and round below the throat seizing, in again over the top of the dead eye and its own part, forming a clove hitch and the end seized down (Fig. 123), or two round turns are taken round the shroud below the nip, and the end seized down (Fig. 124). How are the hearts turned in or secured to the fore and main stays? The same as turning a dead eye into a shroud (Figs. 159, 165); thus the starboard stay is the same as a starboard shroud, and the port stay is the same as a port shroud. |

The starboard stay is placed above the port one on the mast head; it is not uncommon to find the heart seized into a long eye splice. Where are the fore stays set up? To collars on the bowsprit (Fig. 159), or in some long ships to the knight heads. Where are the main stays set up? To the knight heads, or to a crosspiece before the fore bitts. How are the lanyards of the fore and main stays rove and secured? Four turns are passed, and the lanyard is then set up on both ends, the ends are expended in riding turns, and all parts are kept in the places by good spunyarn seizings (Fig. 125). RIGGING OF THE YARDS.

Every yard must have at the yard arms – A Footrope – for the men to stand upon. A Head easing strop } for bending the sail to. A Jackstay } A Brace, for altering the position of the yard when necessary. And a Lift – for supporting the yard arm. At the slings or bunt –

Slings – Tie Blocks or halliards – to support or hoist it. And quarter blocks – for the clewlines, and the sheets of the sail set above it to reeve through. How is the bunt of a royal or top-gallant yard rigged? With slings, a parrel, and strops for quarter block (Fig. 131.) (The halliards are sometimes bent to the yards with a studdingsail bend; in which case the slings are not fitted). How is the bunt of a topsail yard rigged? With tie blocks, a parrel, quarter blocks, and a pendant used in sending the yard up or down on the deck (Fig. 133). How is the bunt of a lower yard rigged? With chain slings in the centre, and a jeer block, a quarter block, two truss strops, and a clew-garnet block on each side (Fig. 135). |

How is a royal or top-gallant yard arm, rigged? With a footrope, head earing strop, jackstay, brace and lift. The brace and lift are often spliced into eyes, on an iron ring or band, which makes it easier to rig and unrig the yard arms when sending the yard up or down (Fig. 130). (Sometimes a royal yard has no head earing strop, in which case the earing is secured round the yard arm).

How is a topsail yard arm rigged? With a footrope, head earing strop, jackstay, dog strop for the brace block, and a lift block. A Flemish horse is spliced round the goose neck (Fig. 132). Topsail yards are frequently fitted without Flemish horses, the footropes being secured round the goose neck; a stirrup is then placed on the yard arm in the place of the footrope. This fitting is more convenient for the yard-arm men, but brings a greater strain on the goose neck. A Turk's head should be fitted on the footrope outside of the outer stirrup, to prevent it unreeving in case the goose neck should carry away. How is a fore yard arm rigged? With a footrope, head earing strop, jackstay, yard-tackle pendant, dog strop for the brace block, a lift block and the standing part of the lift (Fig. 136). How is a main yard arm rigged? With a footrope, head earing strop, jackstay, yard-tackle pendant, dog strops for the preventer brace block and after brace block, a lift block, and the standing part of the lift. How is a cross jack yard rigged? In the bunt with slings, truss strops and quarter blocks. At the yard arms with a footrope, brace block and lift. (Jackstays are sometimes fitted). How are the slings of the yards fitted? Each royal and top-gallant yard has a strop rove on the bight round the bunt of the yard. The foremost bight is passed up through the after one and a thimble seized into it; or the after bight is lashed to the foremost parts taut round the yard. The halliards are bent to the,slings with a double bend, or bent round the yard with a studding-sail halliard bend. |

The lower yards have chain slings fitted in the same way, a shackle or large link being used instead of a lashing (Fig. 135). The upper part of the slings is supported by a chock on the after side of the lower masthead, and is fitted with a swivel and slip (Figs. 153, 121). How are the tie blocks on a topsail yard fitted? They are each iron-bound with a swivel, and shackled to bands round the yard, the swivel prevents the tie being injured against the edge of the block when the yard is braced up (Fig. 133). How are the jeer blocks on a lower yard fitted? They are two single blocks placed one on each side of the slings, and are each fitted with two single strops one longer than the other, which are lashed together on the fore-side of the yard with a rose lashing. For the long strop take once and a half the round of the yard and once round the block; for the short, once the round of the block and half round the yard (Figs. 135, 137). (If lashed on the after side, the lashings would be chafed between the mast and the yard). How is the panel fitted on a royal w. top-gallant yard? Two strops, one on each quarter of the yard. One is fitted taut round the yard with a thimble seized in, the other having two seizings is left long enough to pass round abaft the mast and lash to the short one (Figs. 131, 138, 139). How is the parrel fitted on a topsail yard? Two pieces of rope of unequal length, seized one on top of the other; they are puddinged, marled together, and covered with leather, leaving a long and short leg at each end with spliced eyes in them: the centre goes abaft the mast: the long leg on each side goes under the yard, and lashes on top to the short one (Figs. 133, 140, 141). For the long leg take two-thirds the round of the mast and twice the round of the yard. For the short, two-thirds the round of mast, and allow for splicing in each. How are truss strops fitted? Four chain strops with the ends lashed together on top of the yard with a rose lashing: a shackle is fitted to each |

on the after side of the yard. The two strops which are used for the starboard truss are lashed, so that the shackles on the after side of the yard may lie a little higher than those for the port truss (Figs. 135, 142, 143). In placing the truss strops on the yard, those for the truss pendants to shackle to are placed inside on one quarter of the yard and outside on the other: this keeps both hauling parts clear. Note. – On the cross-jack yard, there is only one strop each side.

How are the truss pendants rove? Forward through a block shackled to a bolt on the after horn of the trestle-tree, down through a large shackle in the truss strop on the quarter of the yard, led round abaft the mast and shackled to the truss strop . on the opposite quarter. The cross jack truss is rove with the bight abaft the mast, the ends passed up through the shackle of truss strop, one on each side and a block shackled to each end. How are the quarter blocks on a royal yard fitted? Two single blocks fitted to hook on to the quarter strop on the royal yard. How are the quarter blocks on a top-gallant yard fitted? Two double blocks, fitted to hook on to the quarter strops of the top-gallant yard. (A chain strop is lashed on each quarter of the yard, leaving a link hanging down under the yard for the blocks to hook to, or a single wire strop with two lashing eyes (Fig. 131). How are the quarter blocks on a topsail yard fitted? Two double blocks, each fitted with a single strop, leaving two legs with lashing eyes, which are lashed together on top of the yard with a rose lashing (Fig. 132); or two single blocks on each quarter, one for the top-gallant sheet, and the other for the topsail clewline, fitted in the same way. A becket with two sennet tails secured on the yard, and the quarter block fitted to toggle to it takes the clew higher, and is convenient for shifting topsail yards (Fig. 144); or a strop lashed taut on the yard with a thimble worked in on the fore side, in the same way as working a mingle into the bolt rope of a sail. |

How are the quarter blocks on a lower yard fitted? Two single blocks, each with a double strop leaving two long bights which are lashed together on top of the yard with a rose lashing. The two blocks are lashed together under the yard to prevent them being hauled out towards the yard arms (Figs. 135-145): How are the clew-garnets blocks on a lower yard fitted? Two single blocks, each with a single strop, leaving two legs with lashing eyes, which are lashed together on top of the yard with a rose lashing; or a single sennet tail taken three times round the yard and nailed: this takes the clew of the sail much higher (Figs. 126, 146). Why are the quarter blocks outside the parcel on a royal, topgallant, and topsail hard? To allow them to hang clear of the cap or rigging when the yards are lowered. How are footropes fitted? With an eye splice round the yard arm, the inner ends being lashed to the yard on the opposite quarter with a rose seizing (Figs. 129, 132). On the lower yard the two inner ends lash together and trice up to the slings of the yard (Figs. 134, 135). (The footropes on a topsail and lower yard are frequently fitted with an eye splice round the goose necks).

How are stirrups fitted? They are short legs hanging down from the yard on the after side to support the footropes, and are fitted with an eye splice at each end – one round the jackstay bolt under the jackstay, and the other round the footrope (Figs. 133, 135). When the footrope is secured round the goose neck, the outer stirrup is spliced round the yard arm inside the rigging, taking the place of the footrope. How is a head Baring strop fitted? A grummet strop is fitted round the yard aim with a thimble seized taut in on top of the yard, for the head earing of the sail to secure to (Figs. 130, 136). How is a jackstay fitted? With an eye splice round the yard arm, passed through the jackstay bolts, or strips of leather nailed on the yard, the |

inner ends being lashed together in the slings (Figs, 135, 136). When braces and lifts are single, how are they fitted? With an eye splice round the yard arm (Fig. 130). Top-gallant and royal lifts and braces are frequently spliced into an iron ring which goes over the yard arm (Fig. 152); this is very convenient, as they never alter in size when wet, as the rope does. When top-gallant braces a re double, how are the brace blocks on the yard arm fitted? With a single strop round the yard and the block, with a round seizing between them. How is a topsail brace block fitted? The strop round the yard is called the dog strop, and is a single strop; the block is fitted with two single strops which are connected with the dog strop by two thimbles working one in the other; this leaves the sheave of the block lying perpendicularly (Fig. 147). How is a lower brace block fitted? The dog strop is a single strop round the yard, with a thimble seized in, the block is fitted with a double strop and a thimble, and is connected with the dog strop by the -two thimbles working one in the other; the sheave of the block lying horizontal (Fig. 148). How is the preventer main brace block fitted? The same as the other lower brace blocks. It is placed inside the after main brace, which keeps it from being dragged off the yard arm when the yard is braced up (Fig.148). Why are brace blocks fitted with dog strops? In bracing a yard round, the brace acts in so inaliy different directions, that there would not be play enough in the block strop if fitted taut to the yard. When lifts are double, how is the block fitted? With a single strop round the block and the yard, with a round seizing between them (Fig. 149). |

How is the standing part of a lower lift secured? With a running eye or an outside clinch round the yard arm outside the lift block (Fig. 136). How is a yard-tackle pendant fitted? With an eye splice round the yard arm, or if there is a wire yard-tackle strop on the yard, it is spliced into it with a is the better the two, it small eye splice – this plan of as gives more play to the pendant; and the other end spliced through the strop of the fiddle block; or round the fiddle block which is seized taut in (Fig. 150). How are quarter strops fitted? A grummet strop with a thimble seized taut in; on the royal and top-gallant yards they are used for stopping the yard ropes Out to in sending the yards down (Fig. 131). On the topsail and lower yards they are used for hooking a rolling tackle to in bad weather to steady the yards (Fig. 133). How is the pendant for shifting the topsail yard fitted? Each end has an eye splice. One end is lashed to the quarter of the yard, or rove round the yard with a running eye; the other end is secured with a lizard to the opposite quarter (Fig. 133). STUDDING-SAIL BOOMS.

How is a top-gallant and main-topmast studding-sail boom rigged? With a tack block fitted with a single strop, and toggled over the eye bolt in the outer end of the boom (Fig. 229). How is a fore-topmast studding-sail boom rigged? With a lower halliard block; boom brace and a tack block, each being kept from slipping in by a snotter, which is toggled over the eye bolt in the end of the boom (Fig. 151).How is the lower halliard block fitted? With a long strop round the block and the boom, with two seizings between them (Fig. 151), or a dog strop is fitted |

round the boom end, and the lower halliard block stropped into it. How is the boom brace fitted? With a whip and pendant; the pendant being spliced round the boom end (Fig. 151). How is the fore-topmast studding-sail tack block fitted? With a double strop round the boom and the 1 block (Fig. 151), or a dog strop is fitted round the boom end and the tack block, which has a single strop stropped into it. An iron band on the boom end with studs for the rigging is a snug way of fitting studding-sail booms. BOWSPRIT.

How is a bowsprit secured? By gammonings, bobstays, and shrouds. Which gammoning is put on first – and why? The outer one, having more leverage on the bowsprit than the inner one, must be put on first; otherwise, it would slack the inner one on its being hauled taut (Fig. 154). How are the turns of a gammoning passed – and why? The standing part is shackled round the bowsprit with a running eye, the end passed down through the foremost part of the hole in the cutwater, up round the bowsprit outside of the standing part, and boused taut with a purchase (Fig. 155); whilst the next turn is being passed, the first is stoppered by driving large nails (which are not taken out again) through the links of the chain into the gammoning fish on top of the bowsprit, and by racking it to the first part. In passing the second turn, the end is passed down inside, the first turn crossing it from forwards aft, led throw rh the hole in the cutwater abaft the first turn, up towards the bowsprit, being dipped inside the first part, crossing it from aft forwards, then taken over the bowsprit outside the first turn; the purchase is then put on, boused taut, racked and nailed as before. The rest of the turns are passed the same as the second, forward on the bow- |

sprit and aft through the cutwater, being each boused taut separately (Fig. 157). The last turn coming down from the bowsprit is secured with a strand to the others close down to the cutwater, the end is then frapped round all parts up towards the bowsprit, the last turn forming a figure of eight, and the end secured with good spunyarn (Fig. 158). In consequence of the turns of the gammoning crossing each other they close together on being hauled taut. If the last turns of the gammoning were crossed outside the first turns, the gammoning would be equally as strong, but it would not form so snug a lashing. How is each turn of the gammoning boused taut? A pendant, deck tackle, and capstan are used. The pendant having two selvagee tails, is secured to the bight of the gammoning, close to the bowsprit (Fig. 156). The tackle is secured to the other end of the pendant, and the fall taken to the capstan. In hauling taut assist the chain by hammering it, being careful to have no turns in the chain. If the ship is not alongside a wharf, where the purchases may be worked, the pendant is led through a block secured to one of the bobstay holes in the stem and then inboard through the hawse hole. Whilst one turn is being hauled taut, the next may be passed ready. A single whip is used to overhaul the purchase for the next turn. How is a bowsprit clothed? Inner fore stay collar, inner bobstay collar, first pair of bowsprit shroud collars. Outer fore-stay collar, middle bobstay collar, second pair of bowsprit shroud collars. Outer bobstay collar: and the cap bobstay immediately under the fore-topmast stays (Fig. 159). The inner fore-stay collar is placed two-thirds out, measuring from the knight heads to the outside part of the bowsprit cap; and the three bobstay collars are the diameter of the bowsprit apart. If the forestay collars are,fitted bale sling fashion? Inner bobstay collar, first pair of shroud collars, inner forestay collar. |

Middle bobstay collar, second pair of shroud collars, outer fore-stay collar. Outer bobstay collar, and cap bobstay (Fig. 160). How is a bobstay collar fitted? A single strop with the heart seized into the centre, leaving two equal legs which are fitted with lashing eyes and are lashed together on top of the bowsprit with a rose lashing, the heart being under the bowsprit (Figs. 161, 162). With a chain collar an iron ring is used instead of a seizing to keep the heart in its place. The measurement for a rope collar is, once round the bowsprit, heart, and rope, and allow for splicing. With iron collars, the length taken to make a collar should be twice the round of the bowsprit and one foot added. How is a bowsprit-shroud collar fitted? A single strop with the heart seized in one-third from the end, leaving one leg twice as long as the other; they are fitted with lashing eyes and are lashed together on top of the bowsprit with a rose lashing, the heart being at the side of the bowsprit, and the longest leg underneath (Fig. 163). Measure the same as for bobstay collar. With a wire collar a grummet is used instead of a seizing to keep the heart in its place. How is a forestay collar fitted? A wire strop is fitted, and the heart placed in one bight with a temporary spunyarn seizing to keep it in its place, the opposite bight of the strop is taken round under the bowsprit, brought up and lashed to the collar below the heart, or a grummet is worked round the collar under the heart and the opposite bight is lashed to the grummet with a rose lashing. The heart is left at the side of the bowsprit, and has a large wooden chock to prevent its working round on to the top. Once round bowsprit and heart will give the drift between the warping pins (Figs. 164, 159). If fitted with a double strop.

The heart is seized into the bight of a long double strop with a flat seizing on each side of the heart, and the eyes of the strop lashed together under the bowsprit |