|

|

NAUTICAL DICTIONARY.

|

|

london

printed by spottiswoode and co. new-street square |

|

CONTENTS*.

* Added by the transcriber to facilitate navigation. |

PREFACE.In this great maritime country, with the exception of the present work, the first edition of which has been for a number of years out of print, there is no modern Dictionary of maritime terms. The latest work of the kind is Dr. Burney's edition of Falconer's Dictionary of the Marine, published at a time when the learned editor thought that steam vessels, which had been 'invented and introduced by a native of Scotland,' and successfully navigated on some of the American rivers at six knots an hour, ° might be of use in our navigable rivers and canals and on the Scotch and Irish lakes,' and that, 'even in a military point of view, advantage might be obtained from this invention.' Now, the ocean in every quarter of the globe is traversed by merchant steamers, and almost every ship of war is provided with steam machinery as a moving power. The recent progress of improvement in the building and equipment of ships, and many other causes, have likewise wrought material and most extensive change in the language of seafaring men.. This Dictionary has been framed chiefly for the compiler's own use in performing the duties of a practical and consulting awera,ge adjuster. |

In the first edition, published in 1846, the nautical language was therefore defined with especial reference to merchant shipping. Prior to the year 1854 that edition was rendered more extensively applicable to ships of war. Numerous additional terms, including obsolete words, were also defined, and the information regarding legislative enactments, and the treatises on shipping and marine insurance law and average, along with other matter of a peculiarly fluctuating character, were withdrawn. Care, however, has been taken to give necessary effect to statutory regulations and legal decisions, as well as to the usages of shipowners, merchants, and underwriters, in defining the relative terms. The additional manuscript prepared at that time has now been subjected to a thorough revision, and every effort made to adapt the book to the present condition of nautical science. It is confined mainly to the purpose of definition, but some interesting and instructive general information will be found scattered through its pages. The original matter relating to shipbuilding and seamanship has been mostly derived from the extensive knowledge of Mr. Brisbane, who was a thoroughly experienced shipwright and seaman, several years in command of coasting steamers, and afterwards accustomed to prepare specifications of repairs to sailing vessels and steam ships, and who latterly became surveyor for the New York Board of Underwriters and for the American Lloyd's in the port of Liverpool. The compiler has the grief of intimating Mr. Brisbane's death, which took place shortly after he had, revised the manuscript of the present edition. He was a most friendly, able, and intelligent adviser in everything relating to nautical affairs. |

In particular, either in the preparation of the first edition or during past years in its extension and correction, many contributions and suggestions were obtained, in matters relating to the Royal Navy, from Vice-Admiral W. H. Smyth, Vice-Admiral W. J. Mingaye, Rear-Admiral H. T. Austin, C.B., Captain Robert D. Aldrich, R.N., and Mr. John Bathie, Gunner, R.N.; and on other subjects from Mr. George Bayley, Surveyor of Shipping in London, an experienced shipbuilder; Mr. R. Bruce Bell, Glasgow; Mr. Wm. Clark, Teacher of Navigation; Mr. David Dickie, Shipwright, and Captain Luckie of the Merchant Service, Dundee. Acknowledgement of useful assistance formerly rendered is likewise due to Mr. Brown, late of the firm of Messrs. James Watt & Co., Engineers, London; Mr. David Crighton, Surveyor of Shipping, Dundee; Captain George Duncan of Dundee, now Ship and Insurance Broker, London; Mr. Mather, Engineer, Dundee; Mr. James Maxwell, Gunner, R.N.; Captain James Neish, late of Bombay; Messrs. Ritherdon & Carr, London; Captain Reid, and Captain Sturrock, of the Davis' Straits Whale Fishing, Dundee; Mrs. Janet Taylor, of London; and to many others. It might appear ungrateful to omit special notice also of the constant attention and facilities afforded at the Navigation Warehouse and Naval Academy of Mr. Charles Wilson (late J. W. None & Wilson), Leadenhall Street. In defining the language of seamen, it is often more convenient and clear, if indeed not absolutely necessary, to make use of technical expressions. |

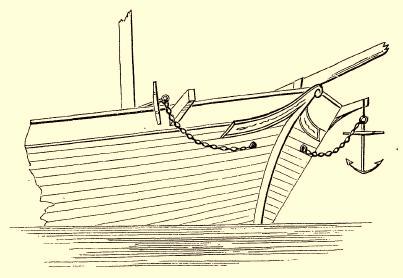

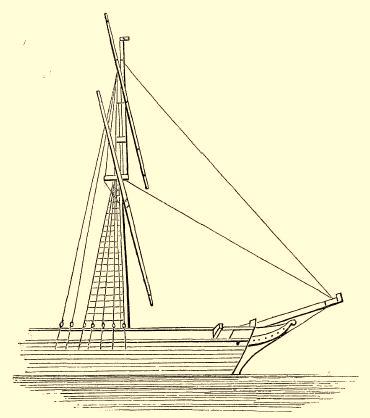

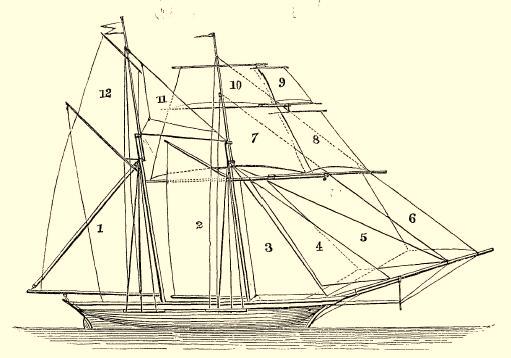

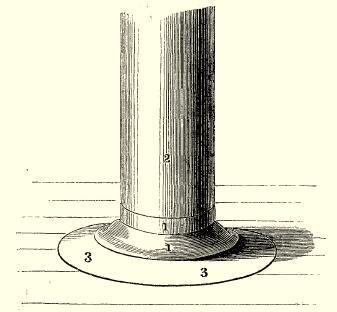

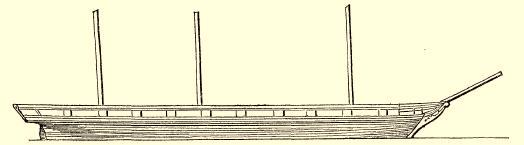

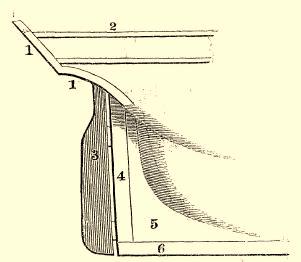

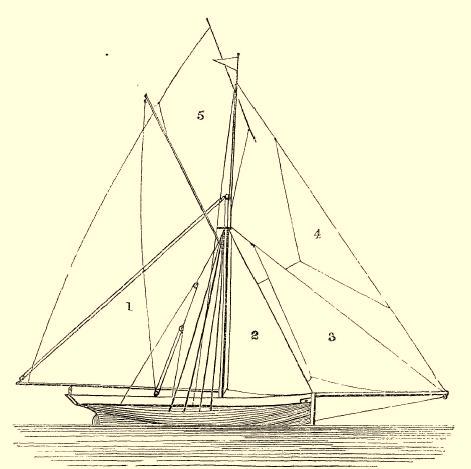

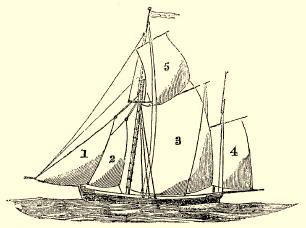

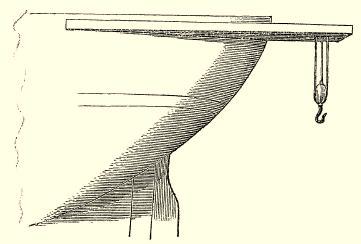

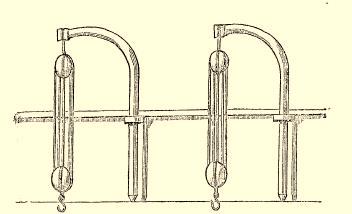

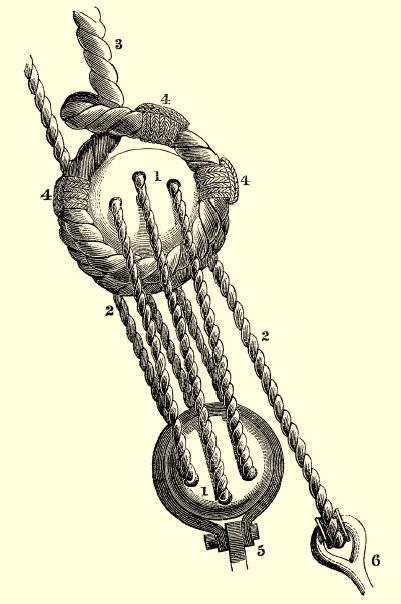

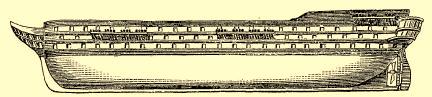

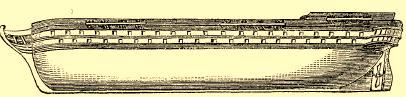

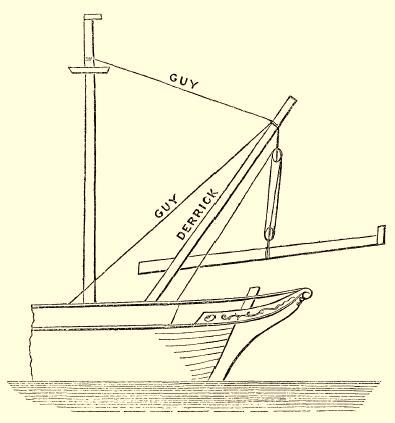

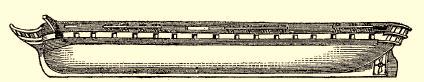

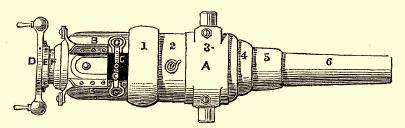

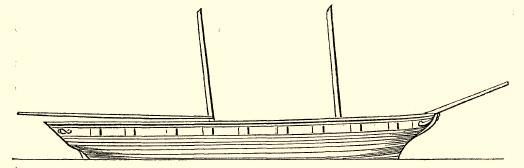

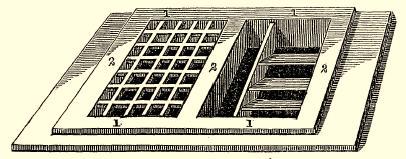

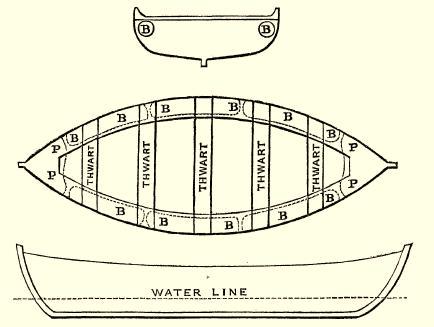

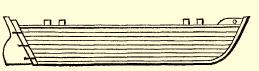

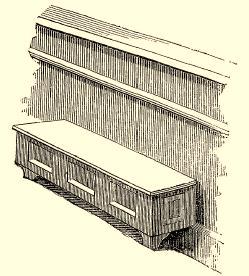

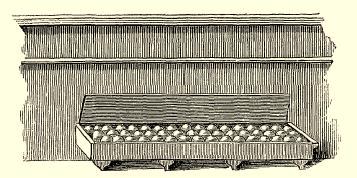

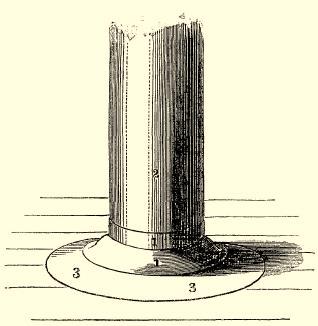

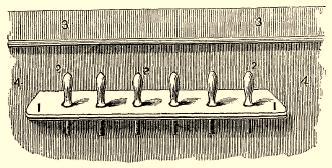

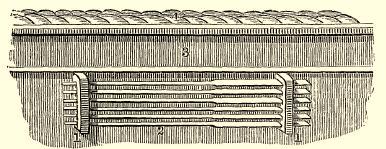

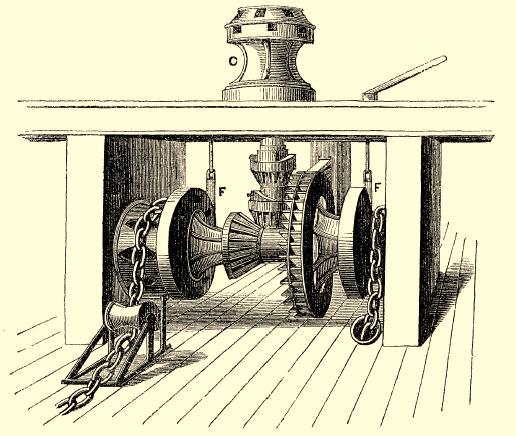

To simplify the definitions, therefore, and to impart a greater interest to the general reader, they are now, to a large extent, illustrated by woodcuts, chiefly from sketches by an eminent artist. The Screw Propeller, in several of its leading varieties of form, the Armstrong Gun, some of the Admiralty models of ships of war, and various nautical inventions, are likewise similarly illustrated; and at the end of the book there are engraved plates of a steam ship, with the side lever condensing engine, formerly in general use for marine purposes, and not yet wholly superseded, and of several kinds of merchant vessels, along with sectional sketches of their frame. Each of the engraved plates has an index prefixed to it. That prefixed to the plate of the steam ship forms also an index to the description of the marine engine, given under the title Steam Engine. The introduction of French words in the Dictionary, and of a French vocabulary, by way of supplement, is intended to give, to a certain extent, a more accurate groundwork for the study of the French nautical language than the ordinary French and English dictionaries afford. Those who wish more extensive information should refer to the able and comprehensive Naval and Military Dictionary of the French Language, by Lieut.-Colonel Burn. The accuracy of the vocabulary has been tested by a careful examination of the definitions in the Dictionnaire de Marine d voiles, par MM. Le Baron de Bonnefoux et Paris, published at Paris in 1848, 'under the auspices of M. Le Vice-Amiral Baron de Mackau, Ministre de la Marine et des Colonies.' Other information of an interesting and useful character has been also derived from that work. |

They constitute a comparative example of the use of the French and English languages on an important nautical subject, and they contain information immediately required by every able seaman and officer in the Merchant Service and Royal Navy. LONDON: 1863. |

|

LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS.

——

PLATES.

————

WOODCUTS.

|

|

|

NAUTICAL DICTIONARY.

ABACA (Fr. Abaca). A kind of banana tree, abounding chiefly in the Philippine Islands, with the fibres whereof they make cordage. This cordage, like coir, has the property of floating in water; and it does not require to be tarred, as it is not subject to rot in water. ABACK. The position of the sails of a vessel when their surfaces are pressed aft by the force of the wind. All aback implies that all the sails are aback. The sails are laid aback (Fr. coiffé) when they are intentionally adjusted in the above manner, either to stop the ship, to deaden her way, or to make her move astern. They are taken aback (Fr. coiffé) when suddenly thrown aback by a change of wind, or through the negligence of the helmsman. See Brace aback and Full. When the action of a marine engine is reversed, so as to urge the steam-vessel astern, the machinery is said to work aback. ABAFT. Behind; nearer or towards the stern of a vessel. This term is not used with reference to things out of the ship. ABAFT THE BEAM. See Bearing. ABANDONMENT (Fr. Abandonnement), in Marine Insurance, implies the yielding up to the insurer all that may be saved of the property insured, when some misfortune, for the consequences of which he is responsible, has taken place, and the circumstances are such as to entitle the assured to recover as for a total loss. ABEAM of any vessel: the same as On her beam. See the article Bearing. Guns are said to be pointed abeam when they are pointed in a line at right angles to the ship's keel. ABLE SEAMAN. See the article Seaman. 1

|

ABOARD, or ON BOARD. Within or on the deck of a vessel. It also means into the ship. See also Keep the Land Aboard, and Tack. Fall Aboard of (Fr. Aborder). To run foul of; to strike or drive against another ship. ABOUT SHIP! The order to tack, or 'go about' (Fr. Revirer). See Tack. Ready About! An order to the crew that all hands be at their stations, ready for tacking, or 'putting the ship about.' ABREAST of any place, means off or opposite to it. One vessel is said to be abreast of another when directly upon the 'line of her beam,' that is, of her midship beam. In this sense it is the same as abeam; but the term Abreast is more peculiarly applicable when the sides of the vessels are parallel to each other and one ship on the line of the other's beam. A-BURTON. Casks are said to be stowed a-burton when placed athwartships in the hold. ABUT. The same as to Butt. ACCOMMODATION-LADDER. See Ladder. A-COCK-BILL. The anchor is a-cock-bill when it hangs down by its ring from the cathead. To cock-bill the anchor is to

bring it into this position previously to dropping the anchor. Yards are said to be a-cock-bill when they are topped up at an angle with the deck. 2

|

ACTION (Fr. Action), in a naval sense, an engagement, a fight between ships or fleets. ADJUSTMENT, in Marine Insurance, the final arrangement of claims for loss or damage, to be settled by the underwriters. An Adjuster of Averages, or Average Stater, is an individual employed to adjust, that is, to make out, statements or adjustments' of such claims, whether of average or of salvage loss. He commonly acts also as an arbitrator in cases of dispute. The adjustment of a ship's compasses is noticed under the title Compass. ADMIRAL (Fr. Amiral), in the Royal Navy, an officer of the highest rank in a fleet, distinguished by a square flag, which is carried above the main-mast. Next to him is the Vice- Admiral, whose flag is carried above the fore-mast. Next, the Rear-Admiral, whose flag is carried above the mizeli-mast. The Admirals, Vice-Admirals, and Rear-Admirals of Her Majesty's Navy are classed into three squadrons, named after the colours of their respective flags, viz., the red, the white, and the blue. These have precedence in the order here noted. The Admiral of the Fleet is the officer of highest rank in 3

|

the naval service. The Union flag is worn by him, as his proper flag, at the main top-gallant-masthead. ADMIRALTY (Fr. Amirauté). The office and jurisdiction of the Lord High Admiral, or rather of the Lords Commissioners appointed for executing the duties of his office (which is now extinct), in taking the general management of maritime affairs, and of all matters relating to the Royal Navy, with the government of it in its various departments. THE High Court Of Admiralty is a supreme tribunal wherein cognisance is taken by the Judge of the Admiralty of maritime cases, whether civil or criminal. He has jurisdiction to decide questions as to the title or ownership of any vessel, or the proceeds thereof, remaining in the registry of the said Court, arising in any cause of possession, salvage, damage, wages, or bottomry, instituted in that court – to take cognisance of all claims for salvage or towage, and for necessaries supplied to foreign vessels – and of all claims and causes of action in respect to any mortgages of vessels arrested by process issuing from the court, and questions relating to booty of war which Her Majesty may refer to its judgment '– and so on. From the judgments of the High Court of Admiralty an appeal may be made to the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council. Vice Admiralty Courts are, for the like purposes, instituted in several of our Colonies. There is also a High Court of Admiralty of Ireland. The Admiralty Court of Scotland was abolished by the Act 1 Will. IV., c. 69, and the cases of which it took cognisance are now prosecuted in the Court of Session, or Sheriff's Courts if civil causes; and 'if of a criminal nature, in the Court of Justiciary or the inferior Courts of Judicature, instituted for the trial of the less important offences.' Droits of the Admiralty. Vessels improperly captured before a declaration of hostilities are considered Droits of the Admiralty, implying 'that they are not given as lawful prize to the captors, but claimed and applied as droits (rights) of the Sovereign.' Goods found derelict, or under the denomination of flotsam, jetsam, or lagan, if not claimed within twelve months, are also deemed to be Droits of the Admiralty. Receivers of Droits of Admiralty, now called Receivers of Wreck. Persons appointed under special regulations of the legislature to take the custody of wrecked property, and to inter- 4

|

pose in matters of wreck or salvage for the benefit of the shipping interests. The office of the Receiver-General, who took the general superintendence of such matters, is now abolished, and his duties are now merged in the Board of Trade. ADRIFT. A ship or boat, or anything on board of a ship, is said to be Adrift, when broken loose from her anchors or moorings, or from its lashings. ADVANCE NOTE. An Advance Note is an order to pay a seaman, or to his order, a sum of money in part of his wages, (an advance, Fr. Avance), within a certain number of days after the sailing of the ship for which he is hired, provided he sail by the vessel. This bill is endorsed by the seaman and may be discounted for him by any person, who will then be entitled to recover it, in a summary manner, from the shipowner or his agent. ADZE (Fr. Herminette). A species of hatchet, having a thin arching blade with its edge at right angles-to the handle. It is used in shipbuilding where the axe or ordinary hatchet cannot be conveniently applied. AFFREIGHTMENT. See Charter-Party, Freight. AFLOAT (Fr. À flot). Borne up by the water. AFORE. Before: towards or nearer the bow of a vessel, spoken of things in the ship. Abaft is the opposite term. AFT. Behind or nearer the stern of a vessel, spoken only of things in the ship. Also, towards the stern (Fr. â l'arrière). To haul aft a sheet means to pull it more towards the stern. This phrase implies the trimming of a sail so as to come nearer to the wind. To ease off the sheet is the reverse. See Fore and aft. AFTER. A term applied relatively as an adjective, to signify next to or nearer the stern. The reverse of Fore. The AFTER-END of a vessel (Fr. Arrière) is her stern. After-Peak. The aftermost part of the hold of a vessel. See Fore-Peak. The After Sails comprehend all those sails which are abaft the centre of the vessel; those upon the fore-mast and bowsprit being termed the head-sails. AGENT. A person employed to transact business with another; the person so employing him is termed the principal. See Factor and Brokers. Navy Agent. An agent employed for behoof of officers or 5

|

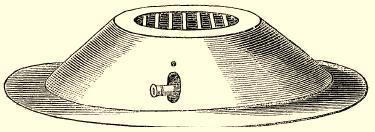

seamen in the Royal Navy, to receive their pay, &c., and to apply it as they may direct. AGROUND. The situation of a vessel when her bottom rests upon the ground. AHEAD (Fr. Avant). Before a vessel's head; farther in advance of her. Astern is the opposite term. The terms are used with reference to the relative position or motion of other objects, and to the movement of the ship herself. See Bearing and Reckoning. AIR-CONE. See description of Steam Engine, Sect. 19. AIR-PUMP (Fr. la pompe à l'air), with its appendages. See description of Steam Engine, Sects. 14 to 19. A-LEE (Fr. Envoyez! Put the helm a-lee). The position of the helm when the tiller is put down to a vessel's lee-side, which makes her head come up in the direction of the wind. A-weather is its position when the tiller is put up in the direction whence the wind blows, which makes the ship's head move to leeward. See Helm. ALLOTMENT NOTES, or MONTHLY ALLOTMENT NOTES, often termed simply Monthly Notes, are orders on a shipowner, by the master or other authorised officer of a ship, to pay any portion of the monthly wages of a seaman, until further advice, to such person as the seaman may direct. ALLOWANCES. The quantum of provisions, &c., served out to seamen on board of a vessel. Also, a term for refreshments given to shipwrights, labourers, or other workmen. See also Chaps. 29 and 30 of The Queen's Regulations as to Allowances for Clothing, Instruments, &c., and Passage Allowances, that is, allowances made for passengers carried at the public expense in ships of war. ALMADY (Fr. Almadie). A name given to a kind of large Indian canoe in some parts of Africa. On the coast of Malabar the Almady was a very sharp-bottomed vessel, pointed at both ends. (Dict. de Marine à Voiles.) ALMANACK (NAUTICAL). See Nautical Almanack and Astronomical Ephemeris. ALOFT. Anywhere up in the rigging, or about the masts or yards of a vessel, particularly above the lower masts. ALONG-SIDE. Side by side. ALTITUDE (Fr. Altitude) of a celestial object: an arc of a vertical circle, contained between the centre of the object and the 6

|

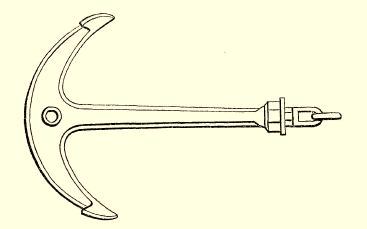

horizon, in other words its elevation above the horizon. When an object is on the meridian its altitude is called Meridian Altitude. By observations of these, the latitude of any place may be ascertained. Altitudes of the sun or moon, taken at sea, require four corrections in order to obtain the true altitude of their centre. These are for semidiameter of the body, dip, refraction, and parallax. The altitude of the sun, or moon, or of a planet, can be observed only at the edge of its disc, not at the centre, hence the necessity for taking the semidiameter into account. But the fixed stars, being at such an infinite distance, appear to us but as luminous points; their semidiameter, therefore, does not require to enter into the calculation in finding the latitude at sea. AMIDSHIPS. In the middle of a vessel or boat, with reference to her length; as, the enemy boarded us amidships; or, with reference to her breadth, as, put the helm amidships, that is, put it in a line with the keel. AMMUNITION. A general name for all kinds of warlike stores, more especially powder and shot. AMPLITUDE of any celestial object: an arc of the horizon contained between the east or west point of the horizon and the centre of the object at the time of its rising or setting. It is termed eastern or western amplitude according as it relates to the rising or setting of the object. When the observation is made with a compass, the result obtained is termed magnetic amplitude, and this will be affected by the variation of the needle. The difference between this observed amplitude and the true amplitude ascertained by calculation thus shews the variation of the compass. See Astronomy (13) and Azimuth Compass. ANCHOR (Fr. Ancre). A well-known instrument, by which, when it is dropped to the bottom of the water, with a cable attached, a vessel is held fast. In this situation she is said to be at anchor. To Anchor, or to Cast Anchor (Fr. Ancrer, mouiller), is to drop or 'let go' an anchor, that the ship may ride thereby. 1. The anchor consists of two hooked arms, for penetrating and fixing themselves into the soil, attached to one extremity of a long bar, the shank, having a ring at its other end, to which the cable is made fast, and the stock, which is attached at right angles to this end of the shank. When the anchor is dropped, the stock serves to direct one of the points of the arms downwards into the soil; the weight of the anchor then causes the point to penetrate 7

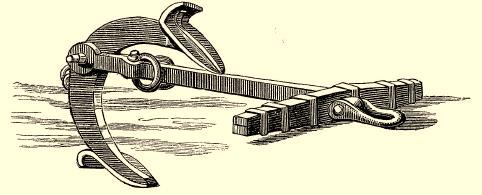

|

more or less, according to the softness or hardness of the bottom; and the action of the vessel on the cable has a tendency to fix it deeper. When the stock is made of wood, it consists of two pieces clamped together by strong hoops, binding them to the shank, and the end of the shank is made square to receive and hold it steadily in its place without turning. To keep the stock from shifting along the shank, there are raised on the latter, from the solid iron, or welded on it, two square tenon-like projections, called nuts. That end of the shank which is next the stock is called the small round; the point where the arms and shank unite, the crown; and the rounded angle at its junction with each of the arms, the throat. A distance equal to that between the throat of one arm and its bill, marked on the shank from the place where it joins the arms, is called the trend. The arms are made either round or polygonal for about half their length; the remainder of each arm consisting of three parts – the blade, the palm, and the bill. The blade, or wrist, is merely the continuation of the arm in a square or rounded form towards the palm or fluke, which is a broad, flat, triangular plate of iron, fixed on the inside of the blade, the use whereof is, by exposing a broad surface, to take the greater hold of the ground. The bill, or pea, is the very extremity of the arm, where it is tapered nearly to a point, for the purpose of penetrating readily into the soil. (Encyclopædia Britannica.) 2. There are statutory regulations requiring the manufacturer of bower, stream, or kedge anchors, to place his name or initials, together with a progressive number and also the weight of the anchor, in legible characters, on the crown, and also on the shank, under the stock of each anchor manufactured by him. 3. Lieut. Rodger, R.N., has made great improvements in the construction of anchors, giving them increased strength and holding power; he says 'that the inefficiency of the large palm is owing to its loosening the ground in front of it, and to its liability to get "shod," and consequent tendency to rise out of the ground; and when this takes place, no dependence can be had on its again taking hold, and therefore another anchor must be let go, when it would otherwise have been desirable to ride by one. 'The small palm, however, does not disturb the ground, which, on the contrary, passes freely over it, and this is to be attributed to its making a more favourable angle with the resisting medium, 8

|

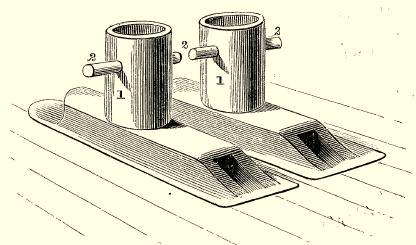

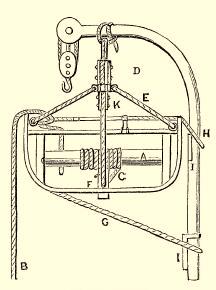

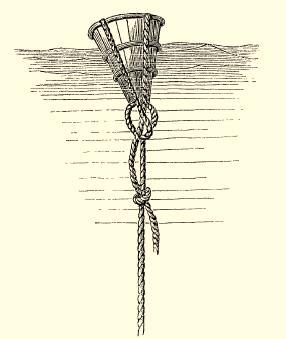

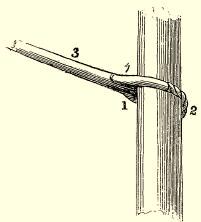

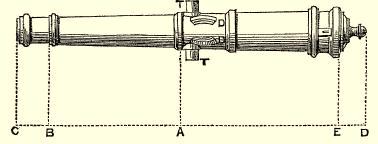

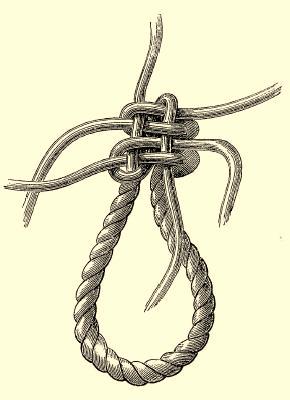

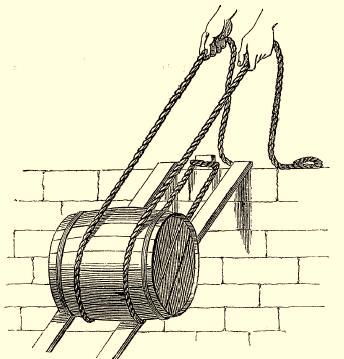

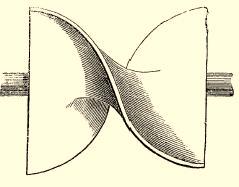

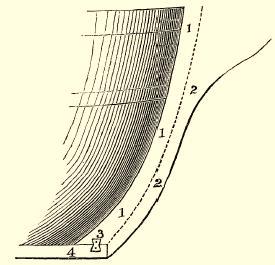

which gives the anchors thus constructed a natural tendency to penetrate deeper, and without the least liability to get "shod." This being the case, a ship will never run away with an anchor with small palms, of the form represented by the accompanying drawing, which, if dragged by riding too short, will again hold on with a sufficient scope of cable; for it has no tendency whatsoever to rise out of the ground.'

He has also made important improvements in the construction of the arms and stock. The advantages of his Pickaxe Kedge Anchor are that 'it holds much better than the kedges of the usual construction, and having no palms, there is no danger of tearing out the gunwale, or capsizing the boat in throwing it.' 4. In Porter's Patent Anchor, the arms are formed by a bar extending from pea to pea without any crossing or welding, joined to the shank by a bolt forming a pivot, whereon they have free motion towards the shank on either side; near the extremity of each arm there is attached outwardly a spur, horn, or toggle, one of which spurs strikes the ground first when the anchor is dropped, and acts as a fulcrum in bringing the bill also upon the ground; the continued strain of the cable then causes the upper arm to descend and close upon the shank, above which it forms an arch. This kind of anchor is not subject to get foul by the cable when slack, entangling itself about the upper fluke of the anchor, and it is said to bite quickly, and to bear a greater strain, as well as to be less liable to be broken by sudden jerks, than anchors of the ordinary construction, combining simplicity, strength, and security in an eminent degree. It is said by Captain Boyd, late of the Royal Navy, not to bite readily, and is therefore 'not a favourite' when necessary to bring up short. (United 9

|

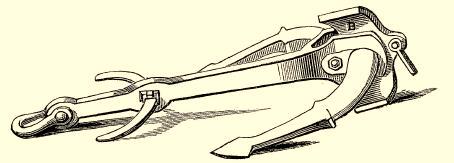

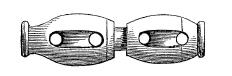

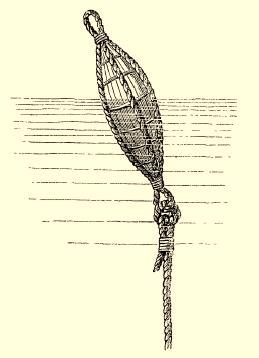

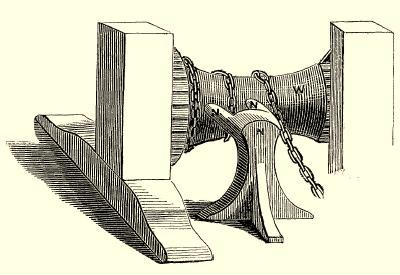

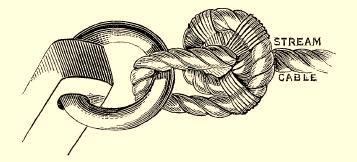

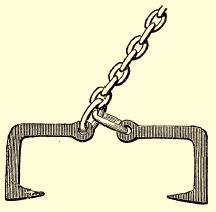

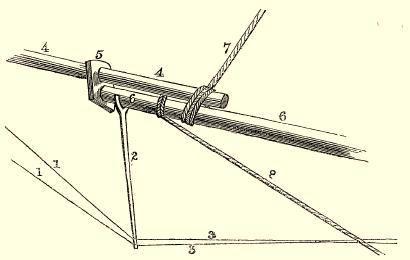

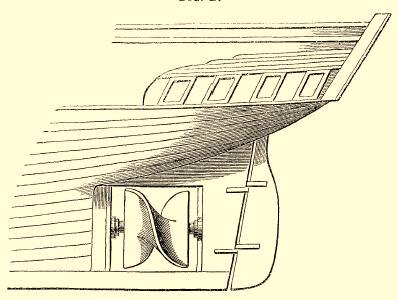

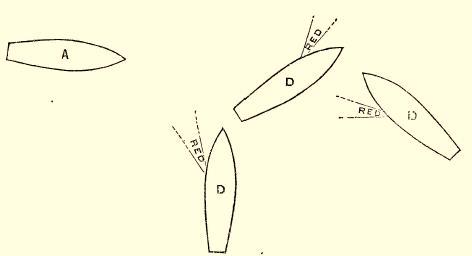

Service Magazine. Practical Mechanic and Engineer's Magazine. Boyd's Naval Cadet's Manual, 236.) Trotman's Anchor is an improvement on Porter's Anchor; it is, as the French term it, a Porter's Anchor brought to perfection. The following is a sketch of Trotman's Anchor shown at the moment when the strain on the cable is acting on the anchor when it is on the ground.

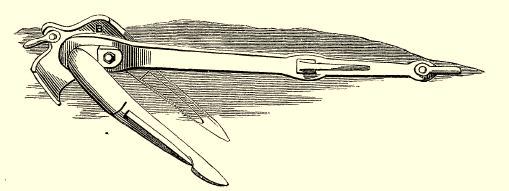

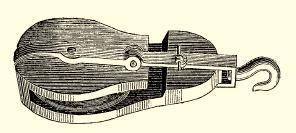

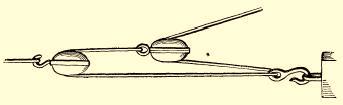

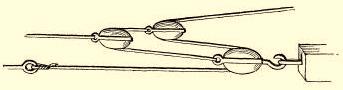

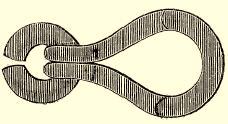

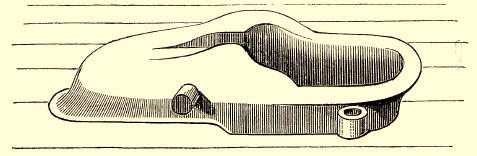

Martin's Anchor is a further modification of the same principle, making the stock to be stopped by the projecting sector B,

martin's anchor when just dropped.

martin's anchor when it has taken hold of the ground, or is imbedded. when the chain begins to raise it from the ground, instead of its being stopped by the shank. In Martin's Anchor both the 10

|

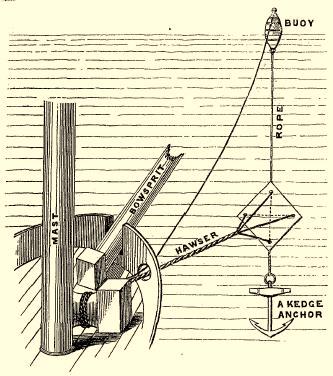

flukes take hold of the ground, instead of only one as in all other anchors. This anchor has very great holding power. It is an improvement on Piper's Anchor, patented in 1822. Sketches of the Admiralty Anchor are given by Captain Boyd, in his Naval Cadet's Manual. Further information on this subject may be obtained in the Treatise on Ships' Anchors, by Mr. George Cotsell. The anchors carried in ships of war and merchant vessels are distinguished (without reference to their construction) by the following names:— 5. The Sheet Anchor, the largest of all the anchors; it is a spare anchor kept in reserve for cases of great emergency. Vessels under 200 tons burden are not furnished with a sheet anchor. 6. The Bower Anchor, viz. the best Bower Anchor, the second in point of size, seldom used on board of merchantmen but when the working anchor is not thought sufficient, or does not hold, or when some accident befals it; and the small Bower Anchor, which in ordinary weather is generally used alone as the working anchor; its cable is usually kept bent and rove through one of the hawse-holes to be in readiness, except in long voyages. All vessels of 200 tons and upwards should be provided with at least three bower anchors. The spare anchor is an additional bower anchor carried in large vessels or in ships of war; in the latter it is called the Waist Anchor. 7. The Kedge, a small anchor which is put out by means of a boat, for various purposes; as, to haul by during calm weather in a river, (an operation which is termed Warping or Kedging); or to keep a vessel clear of her anchor, &c. A small vessel has generally two or more kedges; a ship of great burden carries four kedges or upwards. 8. The Stream Anchor, which is of a size between the small bower anchor and the kedge. It is also used for warping and like purposes, and sometimes as a lighter anchor to moor by with a hawser. 9. See Floating Anchor, Grapnel, Ice Anchor, and also the articles A-cock-bill, A-peek, A-stay, A-trip, A-wash, A-weigh, Jury Anchor, and Under foot. 10. Back an Anchor. To carry out an anchor beyond the one by which a vessel is riding, in order to take off some of the strain, and so prevent it from being dragged. 11

|

11. Cast Anchor. The same as to Anchor. 12. Cat the Anchor. See Cathead. 13. Cock-Bill the Anchor. See A-cock-bill. 14. Come Home. An anchor is said to come home, when it is dislodged through the violence of the wind, &c., straining the cable so as to tear up the anchor from the bed into which it had sunk, and is dragged along; this is especially liable to take place if the ground be soft and oozy, or rocky. In such a case the ship is said to drag her anchor. 15. Come To An Anchor. To anchor a vessel. 16. Drag the Anchor. See above explanation of Come Home. 17. Fish the Anchor. See Fish. 18. Foul Anchor. The anchor is said to be foul, or to be fouled, when it hooks some other object under the surface of the water, or when, by the wind suddenly shifting, or the tide turning, the vessel slackens her strain, and swinging round the bed of the anchor, entangles her slack cable above the upper fluke of it. To prevent the latter occurrence, which might have the effect of dislodging the anchor from its bed, it is usual, in light winds, as she approaches the anchor, to draw the slack of the cable into the ship as fast as possible. In ships of war, so great a scope of cable is veered out, except when there is a lee tide, that the anchor will not foul in this way. 19. Ride at Anchor. See Ride. 20. Sheer the Ship to her Anchor, To steer her towards the anchor while weighing it, so as to keep the wind or current ahead and thus lessen the friction on the hawse-pipe. 21. Shoe of the Anchor. See Shoe. The anchor is said to be Shod, when, in breaking out of the ground a quantity of firm soil adheres to it between the fluke and shank, so as to prevent it from again taking hold. In order to avoid this, the flukes may be greased before letting the anchor go. 22. Sweep for an Anchor. See the article Sweep. 23. Trip the Anchor. See Atrip. 24. Weigh the Anchor. To heave it up from the ground by the cable, in order to prepare for sailing. See Capstan and Windlass. To weigh the anchor by the long boat is performed by hauling on the buoy-rope with a tackle over the boat's davit, To weigh 12

|

it by under-running is done by placing the cable over the boat's davit head, and under-running the cable till the anchor is nearly apeek, when it is tripped by means of the buoy-rope; this is adopted only when the ship cannot get near her anchor for want of water. 25. The following is a Table of the proportional dimensions and weights of anchors and chains for merchant vessels. Compare with those given in Lloyd's Register of British and Foreign Shipping. For those of ships of war reference is made to Boyd's Naval Cadet's Manual, 246, 248.

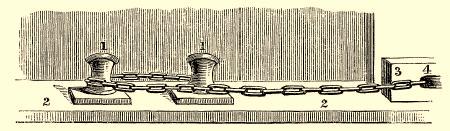

The above Table was originally framed from the tables of Anchors and Chains, issued by Messrs. Pow and Fawens, North Shields; and Mr. J. Gunn, Leith. It has been thought needful now to make only a few alterations in the columns of weights. ANCHOR-DAVIT. See Davits, 1. ANCHOR-HOOPS. See Anchor, 1. 13

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

ANCHOR-LINING. The same as Bill-boards. ANCHOR-RING (Fr. Cigale, Organeau). See description of Anchor. ANCHOR-STOCK. See description of Anchor. Anchor-Stock, in Shipbuilding, the term applied to a mode of working planks by fashioning them in a tapering form from the middle so as to resemble the stocks of anchors, and placing them so that the broad or middle part of one plank shall be immediately above or below the butt of two others. Top and Butt implies a method similar to this. ANCHOR-STOCK-TACKLE. The same as Fish-Tackle. ANCHOR-WATCH. See Watch (Anchor). ANCHORAGE, or ANCHORING-GROUND. A bottom suitable, from its depth and the nature of the ground, for casting anchor upon. Clay is considered to be of the best holding nature. Anchorage also implies a duty charged against ships for the use of a roadstead or harbour. ANEMOMETER (Fr. Anemomètre). An instrument for registering the varying forces and directions of the wind. These are marked by means of a pencil guided by mechanism over a cylinder covered with paper. AN-END. To strike any piece of wood an-end is to drive it in the direction of its length. A spar is an-end, when it is perpendicular to the plane of a vessel's deck. ANEROID BAROMETER. See Barometer. ANGLE-IRON (Fr. Cornière). See Iron. ANTARCTIC. See Zone (Frigid). A-PEAK, or A-PEEK. An anchor is a-peak, when the cable has been drawn in till the ship is almost directly over it, and the vessel is then said to be hove a peak. See A-stay. A yard or gaff is a peak, when it hangs obliquely to the mast. APHELION. That point of the earth's or any planet's orbit, which is at the greatest distance from the sun. That point which is nearest the sun is called the Perihelion. APOGEE. That point of the moon's orbit which is furthest from the earth. The point at which she is nearest to the earth is called the Perigee. The moon is said to be in Apogee or in Perigee when at one or other of these points. The terms Apogee and Perigee are also applied to the like points of the sun's apparent orbit. 14

|

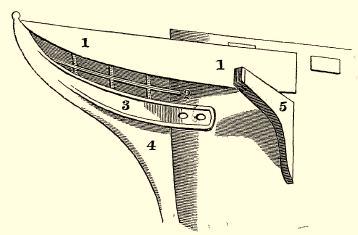

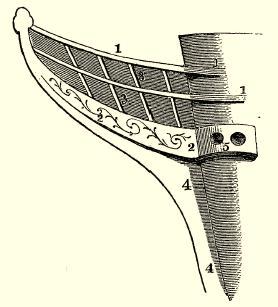

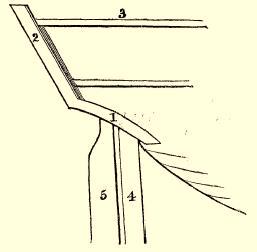

A-PORT. The helm is a port, when the tiller is put to the ship's port side: a-starboard, when put to the starboard side. APPARENT denotes things as they appear to us, in contradistinction from their true situation or description. Thus we speak of the apparent distance, motion, or magnitude of a heavenly body. See also the article Mean Time. To find the true distance – that is, to clear the observed distance (or in other words, the apparent distance ascertained by observation) from the effects of refraction and parallax, is a very intricate calculation in navigation. APPRENTICES TO THE SEA (Fr. Elèves, Novices). Youths who are bound, by a writing called an Indenture, to serve under the master of a vessel for a certain period. APRON, or STOMACH PIECE. A piece of curved timber which is bolted on the inside of a vessel's main-stem to strengthen it and to give shifts to its scarphs. The lower end of the apron is scarphed to the fore deadwood-knee. The fore-ends of the bow planking are bolted to the apron. Plate IV. 13. Apron also signifies a square piece of metal used as a cover for the vent and lock or the detonating hammer of a gun, in order to keep it dry. The Apron of a dock is 'that portion of the structure under and in front of the gates, upon which the sill (the piece of wood against which the gates shut) is fastened down.' ARCH-BOARD. A plank across a vessel's stern immediately under the knuckles of the stern-timbers; on this, or more commonly on a board called the name-board, fitted above it, the ship's name is painted. (Plate II fig. 5.) ARCHIMEDEAN SCREW. See Screw Propeller. ARCHIPELAGO (Fr. Archipel). A considerable number of islands grouped together. ARCTIC. See Zone (Frigid). ARCTIC POLE. The North Pole of the world. See Zone (Frigid). The Arctic Expeditions to discover a north-west passage, impracticable for all useful purposes of navigation, through the frozen waters of the Arctic Seas, have now terminated. To use the words of Sir Charles Wood, the objects to be attained by such an expedition to the Arctic Regions cannot justify the Government in exposing the lives of officers and men to the risk inseparable from it. 15

|

The fatal expedition of Sir John Franklin and his companions, the melancholy traces of which were successively found by Captain Ommanney, R.N., Captain Penney, and Dr. Rae, and finally reduced to certainty by Captain M'Clintock, R.N., has accomplished the discovery of one north-west passage. Another passage through these icy regions has been discovered by Captain M'Clure, R.N. It may be hoped that, with the humane efforts of our own country and of the United States of America in prosecuting the search for Sir John Franklin's ships, all voyages of this description cease. The screw steam yacht 'Fox' in which Captain M'Clintoch prosecuted his adventurous and successful search, was, according to his own account, 'externally sheathed with stout planking and internally fortified by strong cross beams, longitudinal beams, iron stanchions and diagonal fastenings, fitted with a massive iron screw propeller, and the sharp stem cased in iron until it resembled a ponderous chisel set up edgeways.' The expenses of the expedition exceeded 10,000l. ARDENCY. A term used to denote the tendency of a vessel to gripe. If the ship have this tendency, she is accordingly said to be ardent. (Fr. Ardent.) ARM. The extremity of a yard, beam, or bracket. See also description of Anchor. ARM of the Sea. A portion of the sea running into the land, or dividing an island from the main land adjacent. An estuary. ARMADILLA. A small squadron of Spanish ships which was stationed at different points off the coast of Peru and Chili, before these provinces were declared independent states. (Dict. de Marine a voiles.) ARMAMENT OF A SHIP OF WAR. The number and weight of all the guns which she carries. The disposition of the armament on the different decks is explained in Peake's Rudimentary Treatise on the Practice of Shipbuilding, p. 99. ARMED SHIP. A merchant vessel taken into the service of Government at any time during war, and fitted out as a ship of war. ARMOUR PLATED, ARMOUR CLAD, IRON CLAD, or IRON CASED, SHIPS, are ships of war fitted with iron plates on the outside to make them shot proof. The casing of iron is called Armour plating. See Cupola Ships, Shield Ship, and Ericsson's Floating Battery. 16

|

ARMOURER OF A SHIP OF WAR. A petty officer, whose duty is to repair and clean the small arms, namely muskets, pistols, tomahawks, and boarding pikes. He used to do all kinds of smith work on board, but men of war now carry a blacksmith for this purpose. ARMSTRONG GUN. See Gun. ARSENAL (NAVAL). A magazine or place of deposit for ammunition and other naval stores. The principal Arsenals in this country are Woolwich Arsenal and the Gun Wharfs at Portsmouth and Plymouth. ARSENIC. This poisonous mineral substance is mixed with coal tar, or both coal and vegetable tar and sulphur, thinned with naphtha to reduce it to a proper consistency, for paying the bottoms of vessels, as a temporary protection to the plank from worms. ARTICLES OF WAR. Certain regulations for the better government and discipline of the Royal Navy. They are established by Act of Parliament. ARTILLERY (ROYAL MARINE). See Marines. ASCENSION. The right ascension of a celestial body is an arc of the equinoctial contained between the first point of Aries (viz. the point where the equinoctial and ecliptic intersect each other at the vernal equinox) and that point of the equinoctial which is cut by a meridian passing through the body. See the articles Astronomy, 9, and Declination; and the Nautical Almanack, p. 516. The Ascensional Difference is an arc of the equinoctial intercepted between the sun, fixed star or planet's meridian, and that point of the equinoctial which rises with the object. The Oblique Ascension or Descension is the sum or difference of the right ascension and ascensional difference. (Norie's Epitome.) ASHORE. On the shore or land. Aground. ASLEEP. The canvass is said to be asleep when there is just as much wind as to fill the vessel's sails and keep them from shaking. ASSURANCE. See Insurance. A-STARBOARD. See A-port. A-STAY. The anchor is a-stay when, in heaving it, the cable forms an acute angle with the water's edge. This is called a long stay peak or a short stay peak according as the anchor is further from or nearer to the ship, When almost up and down it is said to be apeak. 17

|

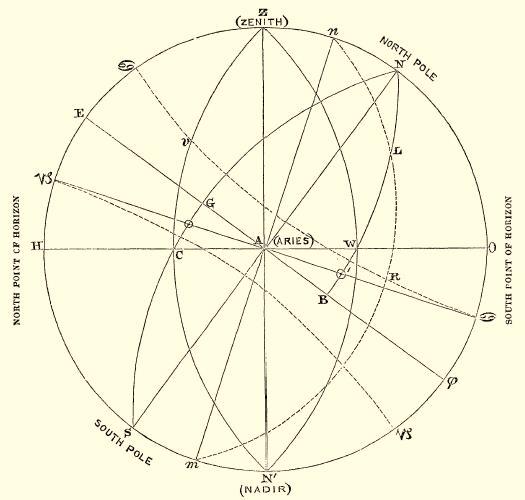

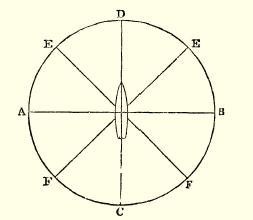

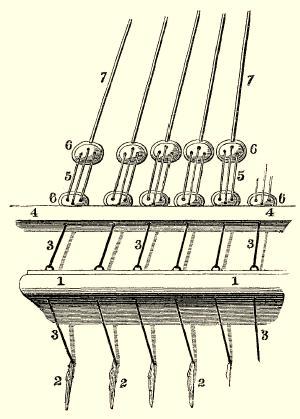

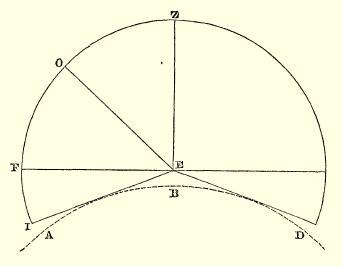

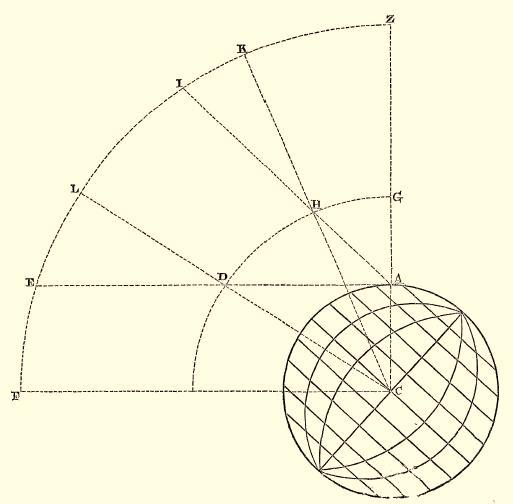

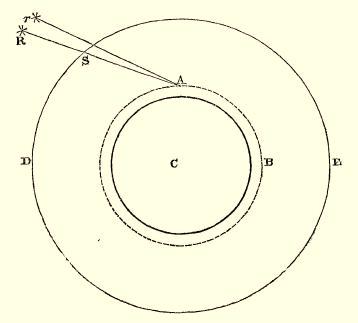

ASTERN. Behind a vessel's stern; further in that direction. See Ahead and Bearing. To Drop astern, or to Full astern, is to lessen a ship's way, so as to allow another to get ahead of her, whether intentionally or otherwise. ASTRONOMY (NAUTICAL) (Fr. Astronomie Nautique). The science which treats of the heavenly bodies so far as relates to the purposes of navigation. See the articles Navigation and Nautical Almanack. The following diagram of the celestial sphere, contributed by Mr. William Clark, Teacher of Navigation in Dundee, illustrates the definitions of many astronomical terms throughout this dictionary.

1. n a s represents the axis of the sphere, or globe; n the north pole, s the south pole, of a celestial 2. e a ø the equinoctial, or equator. 3. h o the horizon. 18

|

4. vs ♋ the ecliptic; n its north pole, m its south pole. 5. ♋ ♋ the tropic of Cancer (parallel to the equator), the sun's greatest 6. vs vs, the tropic of Capricorn (parallel to the equator), the sun's 7. z v c n (or z w n'), an azimuth circle, or vertical circle [z a n' the 8. a ☉, the sun's longitude, an arc of the ecliptic measured from Aries. 9. a g (or a b, if the sun were in the horary circle n l w b), the sun's right 10. g ☉, sun's south declination, an arc of a meridian (the sun being 11. b o', the sun's north declination (the sun being supposed at ☉'). 12. g a ☉ (or b a ☉'), the obliquity of the ecliptic, or the angle formed by 13. a c (or a w), an amplitude. 14. c o (or h c), an azimuth. 15. l r, the latitude of a star, its distance north from the ecliptic (the star Notice may here be taken of a publication by Mrs. Janet Taylor, London, which appears to be a very useful one: namely, A Planisphere of the Stars on a black ground: exhibiting a view of the heavens in three maps, with the distances, magnitudes, and relative positions of the fixed stars; accompanied by a book of directions to assist the student in acquiring a knowledge of them, containing various problems, and a short sketch of the planetary system, &c. For the use of seamen there is published a set of Celestial maps by Mr. J. W. Norie in one volume, with a book of explanations for acquiring a knowledge of and finding the principal fixed stars in the heavens. It is peculiarly adapted to the purpose of finding the stars proper for ascertaining the latitude and apparent time at sea, the longitude by lunar observations, &c. On this subject generally the leading work in the catalogue of nautical publications is A Cycle of Celestial Objects, for the use of Naval Officers and private Astronomers, observed, reduced, and discussed by Captain (now Vice Admiral) W. H. Smyth, R.N. A-TAUNT, or A-TAUNTO. See Taunt. ATHWART-HAWSE expresses the transverse position of a vessel when driven across the fore-part of another, whether they come into collision or not; it is most commonly applied to the case of a vessel under sail coming across another which is lying at anchor. The sailing vessel is said to come athwart-hawse of the other. 19

|

ATHWART-SHIPS. Across the ship. The reverse of Fore-and-Aft. ATHWART THE FOREFOOT is a phrase applied to a shot being fired across a vessel's way, a little ahead of her, as a warning to bring to, or to drop astern. ATMOSPHERIC, or SINGLE ACTION, ENGINE. A condensing steam engine (Fr. Machine à, Vapeur Atmosphérique) in which 'the downward stroke of the piston is performed by the pressure of the atmosphere acting against a vacuum.' (Murray's Treatise on Marine Engines, 16.) See Double Acting Engine. A-TRIP. The position of an anchor when it is raised clear of the ground. A-weigh has the same meaning. The operation itself is called tripping the anchor. The topsails are said to be a-trip, when they are just started from the cap in hoisting. In like manner, an upper mast is said to be a-trip, when by means of the tripping-line it is started, preparatory to being sent down. AUGER. A tool, consisting of a long iron shank having at one end a cross socket into which a wooden handle is fitted, and at the other end a grooved piece of steel somewhat resembling a bit, welded to the shank. It is used for boring large round holes. AUGMENTATION OF THE MOON. The increase of her apparent diameter occasioned by an increase of altitude. AUTOMATIC BLOW OFF APPARATUS. See Steam Engine, Sect. 45. AUXILIARY AND RESERVE RUDDER (Mulley's). See Rudder. AVAST. Enough; stop; cease. AVERAGE (Fr. Avarie). There are three kinds of average, viz. General Average, Particular Average, and Petty Average. The term, however, is mostly used with reference to the two former, and in its original acceptation it denoted only general average. When a ship has put into a port in distress, she is said to have arrived 'under average.' Petty Average is now obsolete; it is what is referred to in the printed part of a bill of lading, by the words 'average as customary;' but this clause is superseded by the agreement that the stipulated freight shall be in lieu of port charges and other expenses, which are the things originally denominated 'Petty 20

|

Average.' Any charges of an ordinary nature, such as port dues, &c., incurred incidentally and not through sea perils in the course of a voyage, are denominated petty average. General Average arises in consequence of any sacrifice being voluntarily made under circumstances of danger, or extraordinary expenses incurred, in the course of a sea adventure, for the joint preservation or benefit of ship and cargo; and it implies an assessment or contribution levied on all the parties interested in the ship, freight, and cargo, to make good the loss which has thus fallen upon one or more of them. Particular Average is a term used to signify damage or partial loss unavoidably happening to any of the individual interests, whether ship, cargo or freight, by one of the perils covered by a policy of marine insurance. Particular Average on Ship. Under this head are included damage sustained from being driven ashore, or from coming into collision with another vessel – by lightning or accidental fire- plunder or damage in consequence of capture by pirates or an enemy – damage to the ship's upper works, &c., by shipping heavy seas – and similar losses. Particular Average on Goods. This term, according to its ordinary acceptation among merchants and underwriters, denotes loss by depreciation in the value of the goods sustained by their being sea-damaged, calculated upon the amount insured. It has also been virtually and properly applied in practice to charges incurred for the purpose of staying the progress of sea-damage. A more extended meaning has been lately applied to the expression by two of our courts of law, but without proof being had of the commonly accepted interpretation of it, the case not having been brought forward as a trial by jury, but in the form of a question for the opinion of the judges. Particular Average on Freight, says Mr. Stevens, can arise only from a total loss of part of the cargo, and it is therefore correctly termed a partial loss on freight. This may arise either from the article of which the freight is insured being washed out of the package which contained it, or from its being lost in bulk by one of the perils insured against. (Stevens' Essay on Average, p. 174.) AVERAGE ADJUSTER (Fr. Dispacheur), Average Stater, or Adjuster of Averages. An individual engaged in the business of making up statements to show the proper 21

|

application of loss, damage, or expenses incurred in consequence of perils or accidents in the course of a sea adventure, whether as between the shipowner and merchant, or between either of them and his insurers. It is necessary that he should have an extensive knowledge of maritime law, of the practice and usages of marine insurance, and general and particular average, and of the phraseology used by shipwrights and seamen. He ought not to be a shipowner, merchant, underwriter, or marine insurance broker. He usually acts as an arbitrator in cases of dispute under the order of any court of law or otherwise when required. AVERAGE AGREEMENT. A written agreement signed by the consignees of a cargo, binding themselves to pay any proportion of general average that may justly arise against them in consequence of some accident with which the ship has met. It is not drawn up in the form of a bond, and ought not to contain an arbitration clause. AVERAGE STATER. See Average Adjuster. A-WASH. At the surface of the water. Heave and a-wash is an encouraging call given during the act of heaving, when the anchor-ring is just out of the water, and the stock is seen to stir the surface. A-WEATHER. See A-lee. A-WEIGH. The same as A-trip when applied to an anchor. AWNING (Fr. Tente). A canopy or covering of canvass over a ship's deck, or over a boat, as a protection from the sun, rain, or night dews. In a ship, the edges of the awning are supported by iron stanchions fixed in the rail, and it is suspended from the middle by a crowfoot, which is formed by a number of small lines rove through a circular piece of wood with holes in it, called the euphroe, hung by a whip from the masthead. Side awnings are termed curtains. In East India ships, the awning also signifies part of the poop deck which is continued forward beyond the bulkhead of the cuddy. (Norie's Epitome.) AXIS OF THE EARTH. In Astronomy, an imaginary line passing through the centre of the earth, round which axis it revolves once in twenty-four hours; the extremities of this line are termed the poles, the one the North, or 'Arctic' Pole, and the other the South or 'Antarctic' Pole. Around this line, extended both ways to the sphere of the fixed stars, the heavenly bodies appear, by the motion of the 22

|

earth on its axis, to perform their diurnal revolutions: it likewise determines two fixed points in the celestial sphere, the north celestial pole, and the south celestial pole. The star nearest to the north celestial pole is called the pole-star. Of the two poles of the earth, that which is above the horizon of an observer is relatively termed the elevated pole; and the other, the depressed pole. See Astronomy, 1. AZIMUTH (Fr. Azimut) OF A CELESTIAL BODY. An arc of the horizon contained between the azimuth circle or vertical circle passing through the centre of the body and the north or south point of the horizon; in other words, the angle formed at the zenith by this vertical circle and the meridian of the, place of an observer. See Astronomy, 14. The most favourable moment for the observation of the azimuth of a celestial body is in general that which approaches nearest to its rising or setting. But the body must have sufficient altitude, at least six degrees, above the horizon, to enable the refraction to be estimated exactly, and the corrected altitude of the object observed, at the same moment, to be deduced with precision. If the azimuth be ascertained by means of an azimuth compass, this will be affected by the variation of the magnetic needle, and it is termed the observed or magnetic azimuth. By comparing it with the true azimuth, the variation of the compass, therefore, is obtained. Azimuth Circles, called also Azimuths, or Vertical Circles, are great circles of the celestial sphere passing through the Zenith and Nadir, and consequently intersecting the horizon at right angles. That vertical circle which passes through the east and west points of the horizon is termed the prime vertical. See Astronomy, 7. THE AZIMUTH COMPASS (Fr. Compas Azimutal) is an instrument similar to the steering compass, but of superior construction. It is adapted to observe the magnetic azimuths or amplitudes of the sun in order to ascertain the variation of the compass, and is fitted with vertical sight vanes for the purpose of observing objects elevated above the horizon. (Norie's Epitome, and Raper's Practice of Navigation and Nautical Astronomy, &c.) AZIMUTH DIAL (Captain Toovey's). A modification of the dumb-card, showing, when determining the error of the compass, 'both the amount of error and its direction, i. e. the course 23

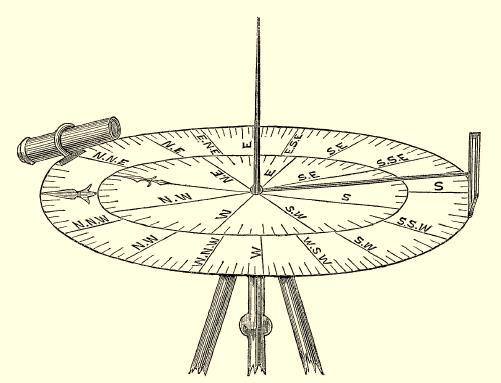

|

by ship's head and the true course on the same card. The instrument consists of a double disc of metal, swinging freely on a tripod, and is of sufficient weight to be always horizontal, whatever may be the list of the ship. The outer rim of the disc is graduated to the points (or degrees) of the compass, and turning on the same centre is a second disc similarly graduated. There

is a small pointer for indicating the direction of the ship's head; and it is also fitted with a style for obtaining the sun's shadow, but this can be removed, and the ordinary telescope and sight vane applied in the usual mode of taking an azimuth of an object.' (Practical Mechanic and Engineer's Magazine.) AZOGA. A name given to the Spanish vessels which carried into America the quicksilver to be used in working the gold mines. (Dictionnaire de Marine à voiles.)

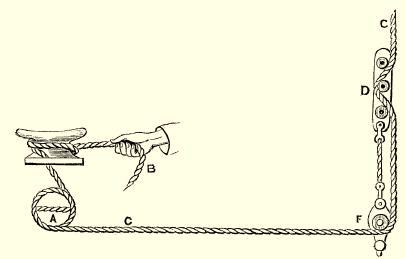

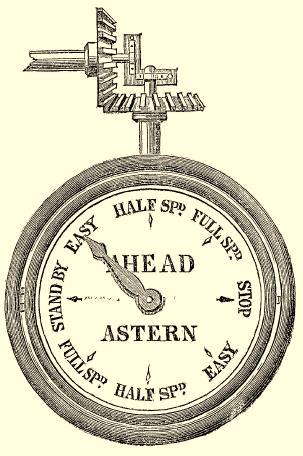

BACK AN ANCHOR. See Anchor, 10. BACK ASTERN, in rowing, means to reverse the action of the oars (or, as it is called, to back the oars) so that the boat may move astern. The oars may be backed also on one side only, in order to assist in bringing the boat's head speedily round in this direction. A sailing vessel is backed by means of the sails; a steamer, by reversing the paddles or screw propeller, or in other 24

|

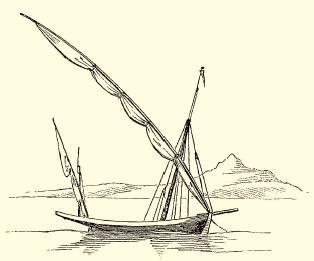

words by backing the engine. See Steam Ship and description of Steam Engine, Sect. 36. BACK AND FILL. Alternately to back and fill a vessel's sails. This is practised when driving in a narrow tideway, in order to keep the ship in the channel without the operation of tacking, the vessel being thus forced alternately ahead and astern by the trimming of the sails. BACK THE SAILS (Fr. Coiffer les voiles). To throw them aback. BACK OF A PIECE OF KNEE TIMBER. See Belly. BACK-ROPES. See Martingale. BACKSTAYS (Fr. Galhaubans). Ropes extended from the topmast, topgallantmast, and royal mast heads to the after part of each channel for the support of these masts. They are distinguished by the name of Standing-Backstays. (Plates III and IV.) Breast-Backstays are those set up with a tackle, and extending from the head of an upper mast, through an outrigger bolted on the side of the top, down to the channels before the standing back- stays: they are used chiefly for topgallant and royal masts; and in large ships for the topmasts also. BACKSTAY-STOOLS. See Stools (Backstay). BAGGALA. A large Arabian ship remarkable by the elevation of its stern, which is ornamented with carved work like the ancient ships of Europe. It has a very high poop. The bows are low and have a great rake. This vessel carries guns on the upper deck, and sometimes on two decks. (Dict. de Marine à Voiles.) BALANCELLE. The French name for a boat used in the Mediterranean, especially at Naples. It is generally sharp at both ends, somewhat like a French fishing boat. It is rigged with a lateen sail, and navigated also with oars. (Dictionnaire de Marine à voiles.) BALANCE-FRAMES. See Frames, 2. BALANCE-REEF. See Reef. BALCONY. See Gallery. BALE A BOAT. To throw water out of her. BALISTIC PENDULUM, in Gunnery, an instrument for finding the force and velocity of a cannon ball. The gun from which the ball is fired is suspended in a gun pendulum for measuring its recoil, opposite to the balistic pendulum, which is 'an iron cylinder suspended so as to spring back easily; it is filled with sand and has in front a cover of lead which the bullet strikes and |

passes through it. The cylinder swings back, and by means of a small catch indicates how far it has moved, and so measures the force and velocity of the shot.' BALK. See Baulk. BALLAST (Fr.Lest). Heavy materials, such as stones, pig-iron, sand, &c., placed in the bottom of a vessel's hold to lower the centre of gravity, and thereby to increase her stability, so that she may not be liable to cant over too much, or to be overturned by the impulse of the wind and waves, as well as to present a greater lateral surface to the resistance of the water when sailing on a wind and thereby check her from falling to leeward. When a vessel has no cargo on board, but only stores for the use of the ship's company, and ballast, she is said to be in ballast. To ballast a ship, or a boat (Fr. Lester), is to put the needful quantity of ballast on board of her. Unless stones, metal, or other such material, cannot be obtained, it is not considered proper, nor perhaps warrantable, to take sand ballast, which is apt to get to the pumps and choke them, even when every precaution is used by clearing the limbers, by protection with matting and otherwise. (Lorimer's Letters to a Young Master Mariner.) The impropriety of taking sand ballast is the greater when the ship has a perishable cargo on board. The advantages of water ballast are treated of in Grantham on Iron Shipbuilding, p. 83. See Water Ballast Platform. In ships of war, pig-iron alone is used for ballast. See Kentledge and Limber-Kentledge. BALLASTAGE. A rate levied for supplying ships with ballast. In the river Thames ballast is put on board of ships by means of ballast lighters fitted for the purpose; this is subject to special regulations of the port, under the superintending control of the Ballast Master. BALLAST MARK. See Water Lines. BALLAST PORTS. Ports cut in the sides of a vessel for taking in and unloading ballast, &c. See Port. BALLAST SHOVEL. An iron shovel generally formed with a square spoon, used in heaving ballast. BALSA, and BALZA. A sailing canoe of Ceylon. A name given to certain kinds of boats, or rather rafts used as boats on the West Coast of South America. BANDS. Strips of canvass sewed across a sail to strengthen 26

|

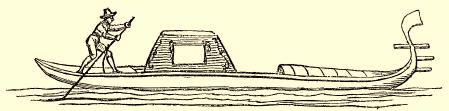

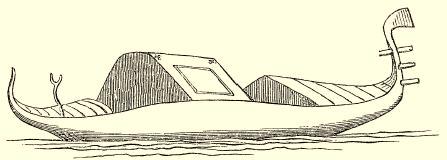

it; such as reef-bands, which are put on in the way of the reef- points. See also Rudder-Bands. BANIAN DAYS. The name which was given to those three days of the week on which, according to former custom on board of ships, the sailors had no flesh meat served out to them. So called after Banians in India. BANK (Fr. Danger). An accumulation of sand or other soil, either elevated somewhat above the surface of the sea, or over which there is shoal water. On charts, banks are indicated by dots and reefs by crosses. See Double Bank and Fog Bank. BANKA. A canoe of Manila. It is made of a single piece. BANKER. See Banking. BANKING. A term applied to fishing on the banks of Newfoundland. A vessel so employed is called A Banker (Fr. Banquier, Terreneuvier). BAR. A bank or shoal at the entrance of a river or harbour. See also Capstan and Hatch-Bars. BAR SHALLOW. A term sometimes applied to a portion of a bar with less water on it than on other parts of the bar. BARCA-LONGA. A Spanish gun-boat, having many sweeps for impelling her. BARE POLES. A ship at sea is said to be under bare poles when she has no sail set; as in scudding during a severe storm. BARGE (Fr. Acon, gabare). A general name for boats of state or pleasure. A large double-banked boat used by an Admiral or Captain in the Royal Navy.. See Boat, 1. Also a flat-bottomed vessel of burden, used in loading or unloading ships, &c. In vessels of this description (Fr. gabares), when employed for the carriage of goods on a river, or through a canal, the mast, if needful, is made to work upon a hinge, so that it may be lowered in passing under bridges, and hoisted again by means of a tackle made fast to the stem or by the fore-stay. See Lee-Board. Crane-Barge. A low-built barge having a flat bottom, and either square or rounded extremities. It is decked, and is made of great breadth, in order to give stability sufficient to counteract the strain upon the crane with which it is fitted for the purpose of lifting the stones, piles, &c., carried on its deck, to be used in the building of sea walls, timber or stone jetties, and similar erections. 27

|

BARK. A popular name for any small vessel. See also Barque. BARNACLE, or BARNICLE (Fr. Bernacle). A species of small shell-fish often found adhering to the surface of a vessel's bottom. These are not injurious to the plank, but tend to deaden the ship's way. They are found occasionally even on coppered vessels, particularly if the popper has been paid over with coarse oil, which on drying leaves a rough surface; or if the vessel has lain long in still water in a hot climate. BAROMETER (Fr. Baromètre). A well-known philosophical instrument for measuring, by means of a column of mercury in a glass tube, the comparative weight or pressure of the atmosphere. This is called the Mercurial Barometer. The Aneroid Barometer, invented by M. Vidi, measures the variation of the atmosphere by the pressure of the atmosphere upon a metallic box hermetically sealed. It is described by Mr. Belville in his Manual of the Mercurial and Aneroid Barometer 1858. Marine barometers are constructed in such a manner as to check the oscillations and vibrations of the mercury, which might be occasioned by the motion of the ship. With a view to that important object, they ought always to be hung by the arm which is prepared for this purpose, and not by the upper ring only. The barometer is subject to slight daily variations, particularly towards noon and midnight; but if at any time the mercury fall considerably from its usual height, some material change may be expected to take place, and when it falls very low, for instance in our climate to 29 inches or below that mark, a gale is sure to follow. This instrument is peculiarly useful in high latitudes, and even near the tropics. But within 9 or 10 degrees of the Equator, though storms of long duration are almost invariably prognosticated by the barometer, yet whirlwinds and squalls of a few hours' continuance are said to be sometimes experienced without any fall of the mercury. In the evidence given some years ago by Captain (now Rear Admiral) Fitzroy before the Committee of the House of Commons on Shipwrecks, he attributed the loss of many vessels to the neglect of the use of this instrument, whereby they have either closed the land when at sea, or put to sea at improper times, and so been overtaken by bad weather coming on suddenly. Every vessel, 28

|

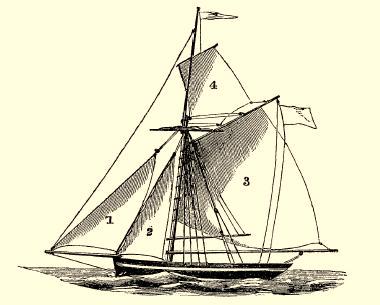

he observed, ought to have either a barometer or a sympiesometer, which is an efficient substitute for it. Important information on this subject is contained in the Introduction to Horsburgh's India Directory (from which some of the above particulars are extracted), in Lieut. Jenning's Hints on Sea Risks, and in Mrs. Taylor's Diurnal Register for the Barometer, Sympiesometer, and Thermometer. The Barometer Manual published in 1861 by Rear Admiral Fitzroy, Chief of the Meteorological Department at the Board of Trade, contains an explanation of his Storm Warning Signals in use at different stations in the British Islands, and of the Weather Tables now published daily in the Times, &c. The Weather Book since published by Admiral Fitzroy is a Manual of Practical Meteorology, explaining the use of meteorological instruments, such as weather glasses on land as well as at sea, and giving full details of the present system of 'Meteorologic Telegraphy.' BARQUE, or BARK (Fr. Barque). A three-masted vessel having her fore and main masts rigged like those of a ship, but her mizen mast rigged like a schooner's main mast. (Plate III.) BARRATRY (Fr. Baratérie). Any fraudulent or illegal act on the part of the master or mariners, or criminal conduct in breach of the trust reposed in them, to the prejudice of the owners of a vessel, and without the consent or privity of the latter. A master who i3 part owner can commit barratry against his co-owners, or against the freighters. BARREL-BULK, in Shipping, a measure of capacity for freight, equal to five cubic feet. Eight barrel bulk are equal to one ton measurement. (Waterston's Cyclopcedia of Commerce.) BARRICADE. A wooden fence at any part of a vessel formed by rails and stanchions. BARTON, or properly BURTON. 'A small tackle is usually called a jigger: a larger one a Barton.' (Boyd's Naval Cadet's Manual.) See Burton. BASIN (Fr. Bassin). The same as a Wet Dock. The term basin is also applied to a portion of a tide-harbour, having a narrow entrance, and forming an inner harbour sheltered and commodious for shipping. BATTENS. Long narrow slips of wood nailed to the coamings of a vessel's hatches in order to secure the tarpaulins which are placed over the hatches when required. This is called battening 29

|

down the hatches. Bands of iron are sometimes used for the purpose instead of wooden battens, especially in coasters. Battens (sometimes called in cant phrase Scotchmen, but properly Chafing-Boards) are also seized upon rigging to prevent its being chafed. Battens are likewise nailed for this purpose on the after side of the yards. In Shipbuilding, battens are used for applying on the side of the vessel in order to determine the sheer, as well as to fair the ship; and for drawing lines by in the moulding loft. See Deals. Hammock-Battens. See Hammock-Racks. BATTERIES (FLOATING). Vessels fitted for harbour defence. Seealso Floating Battery. BAULK, or BALK. In Shipbuilding, a piece of plank nailed across each of the frames to keep them at their proper breadth till the vessel is planked outside. They also get the name of Cross-Spales or Cross-Pawls. See Bilgeways and Spaling. The name of Balks is also given to short pieces of timber, from five to twelve inches square, imported from certain places abroad. BAY (Fr. Baie). A kind of small gulf not running very deep into the land. Sick Bay. See that title. Bays, in a ship of war. The starboard and port sides between decks before the bitts. (Darcy Lever.) BAYDAR. A hark or canoe of the north coast of Siberia, Kamtschatka, and the north-west coast of America. It is made of the skins of seals joined together by flat seams sewed with the sinews of these animals, and is kept at its proper stretch by a frame of wood work. (Dict. de Marine à Voiles.) BAY-ICE. See Iceberg, 3. BAZARAS. A large flat-bottomed pleasure-boat in use on the Ganges; navigated with sails and oars. (Dict. de Marine à Voiles.) BEACH. The sea-shore, the strand. See Careen. TO BEACH (Fr. Ensabler) is a term used to denote the act of intentionally running a vessel ashore in order to preserve her from sinking after having sprung a leak, or when she is otherwise placed in circumstances of inevitable danger. See Stranding. It is also applied to the act of running a vessel up on the beach for the purpose of loading her, &c., at a place where there is no other accommodation. BEACHMEN. A term applied to boatmen, &c., who land 30

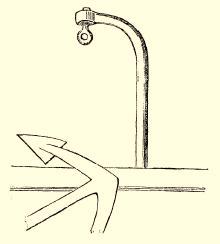

|

people on a beach, especially in places where there is a heavy surf. See Catamaran. BEACON (Fr. Balise). Any mark or sign erected on the coast, or over rocks or shoals, for the safe guidance of vessels. BEACONAGE. A payment levied for the use and maintaining of beacons. BEAMS (Fr. Baux). In Shipbuilding, strong pieces of timber resting on the clamps or shelf-pieces, and extending from the timbers on one side to those on the other side of the vessel; they are secured to the timbers by means of knees, and bind the ship together, besides acting as the support of her decks. (Plate II. fig. 6.) 1. A vessel is said to be on her beam ends, when heeled over so that her beams are vertical or nearly so. On the Beam, or Abeam. See Bearing. 2. Break Beams. Beams introduced at the break of a deck. 3. Breast Beams. Those beams at the fore part of the quarter-deck, and after part of the forecastle, in a vessel which has a poop and a top-gallant forecastle. 4. Half Beams, or Fork Beams. Short beams introduced to support the deck where there is no framing, as in those parts where the beams are kept asunder by hatchways. When these do not exceed one half the dimensions of the beams, and are not fastened at their ends by knees or T plates, they get the name of ledges, or in some places, cross-carlings. 5. Hold Beams. The lowest range of beams in a merchant vessel. When there is an orlop-deck, as in the case in large ships of war, these beams support that deck, and hence get the name of the Orlop Beams. (Plate II. fig. 6.) There is in the between decks of a merchant vessel space used as a hold for cargo, &c.; the hold beams are often termed the lower hold beams, in contradistinction from the orlop beams, and the deck beams, that is the beams in the between decks. Paddle Beams. See Paddle Wheels. BEAM ENDS. See Beams, 1. BEAM FILLINGS. See Filling. BEAN-COD. A Portuguese boat. BEAR. A name given to a large holystone with ropes attached to drag it along the decks for the purpose of scrubbing or cleaning them; and also to a coir mat filled with sand used in some ships for the same purpose. 31

|

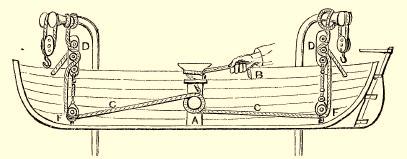

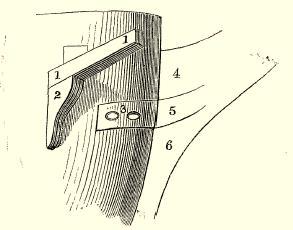

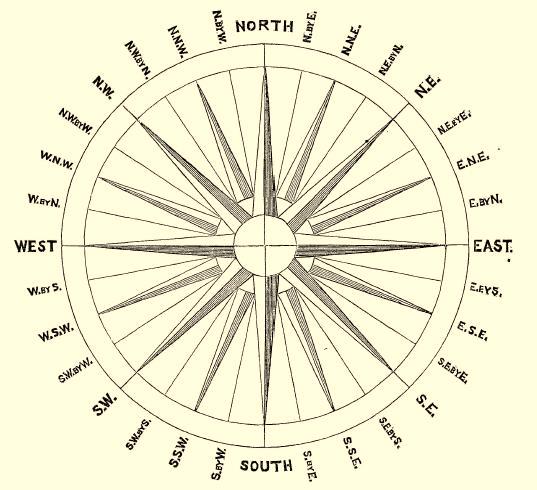

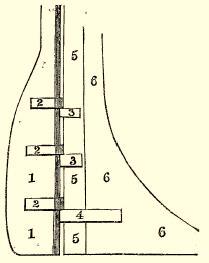

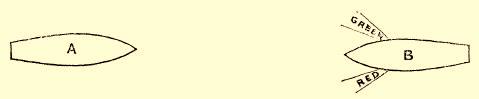

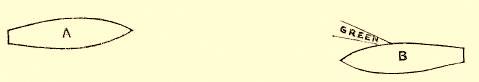

An object bears so and so when it is in such a direction from the person looking. With reference to the wind it is said to bear N. or N.E. &c. according to the quarter whence it blows. See Bearing. BEAR A HAND. To make haste. BEAR AWAY, or BEAR UP (Fr. Arriver, larguer). To make a vessel's head recede from the wind when she is sailing close-hauled, or with a side wind: in either case, this is done by putting the helm up, that is, by putting the tiller up in the direction whence the wind is blowing. BEAR DOWN UPON A VESSEL. To approach her from windward. BEAR IN WITH and OFF FROM the land, imply respectively to steer a vessel towards and from the land. BEAR OFF. To keep anything, in the act of being hoisted or lowered, from chafing against the ship's side. To thrust off. BEAR UP, or BEAR UP THE HELM. The same as to Bear away. BEARDING, in Shipbuilding, diminishing the edge or surface of a piece of timber or plank, &c., from a given line.' (Shipwright's Vade Mecum.) BEARDING LINE. A curved line made by bearding or reducing the dead-wood to the form of the ship's body. The lower points of the timbers come down to this line, which is often called the stepping-line. BEARING. The situation of one object from another with reference to the points of the compass. Also, the situation or direction of any object, or of the wind,

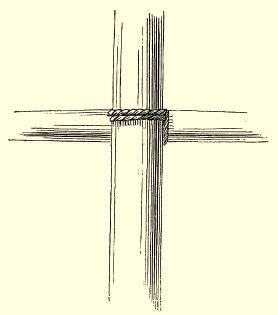

estimated from some part of the ship. These bearings are either On the beam (or abeam), as the lines a and b: Before the beam, 32

|

as the arcs a d and d b: Abaft the beans, as the arcs a c and c b: On the lee or weather bow, as the lines e e: On the lee or weather quarter, as the lines f f: Ahead, as the line d: or Astern, as the line c. (Seamanship both in Theory and Practice.) BEARINGS OF A VESSEL. The widest part of her below the planksheer; that part of her which is on the water-line when she sits upright with a full cargo on board. BEAT TO WINDWARD (Fr. Louvoyer). To sail against the direction of the wind by means of alternate tacks. Working to windward and Turning to windward are terms synonymous therewith. BECALM (Fr. Abner, Cacher, Déventer). A vessel is becalmed when there is not a breath of wind to fill her sails. Any object becalms a vessel, or one sail becalms another, when it prevents the wind from reaching it. BECKET. A piece of rope, sometimes with a knot at one end and an eye in the other, sometimes with its two ends spliced together, used for confining pump gear, oars, or spars together, and for other purposes. A piece of wood in the form of a cleat seized on a vessel's fore or main rigging for the sheets and tacks to lie in (while they are not required) in order to avoid chafing. A ring of rope or iron fixed to the bottom of a block for the standing end of the fall to be made fast to. BED. A flat thick piece of wood, two of which are lodged under the quarters of any cask that is stowed in a vessel's hold, in order to keep it bilge free. Casks are steadied upon the beds by means of wedges called Quoins. See Bilge of a cask. Beds for Guns are pieces of wood for the breech of the gun to rest on. Beds for Mortars, or Bomb-Beds, are solid frames of timber whereon the mortars in a bomb-vessel are supported. BEES (Fr. Violons). Pieces of hard wood bolted to the outer end of a vessel's bowsprit to reeve the fore-topmast stays through. BEETLE. A wooden maul hooped with iron used for driving reeming irons and treenails. See Maul and Reeming. BEFORE THE BEAM. See Bearing. BELAY (Fr. Amarrer). To make fast any running rope by turns round a pin or coil without hitching or seizing: chiefly applicable to running rigging. 33

|

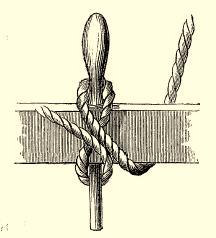

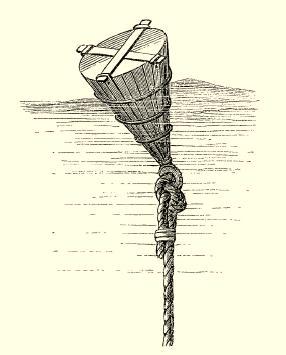

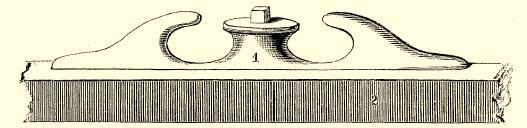

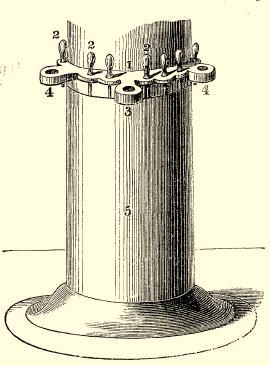

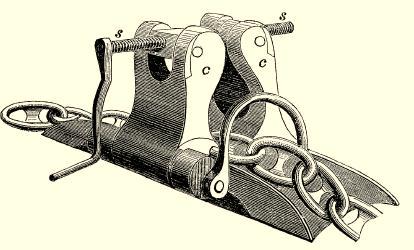

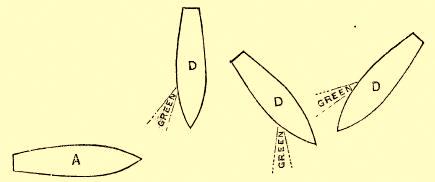

BELAYING PINS are wooden or iron pins, fixed in different parts of a vessel for belaying ropes to. They are illustrated

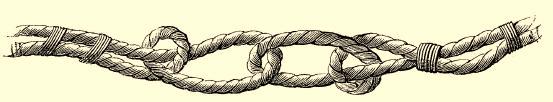

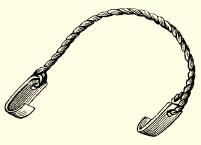

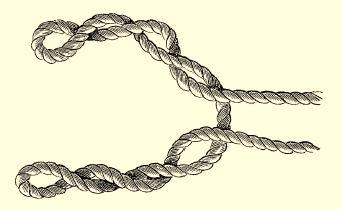

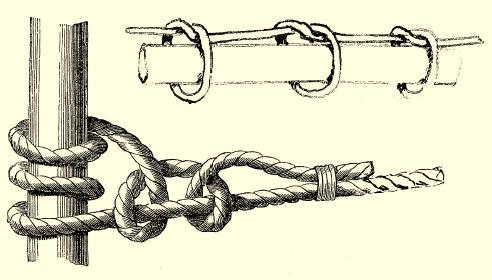

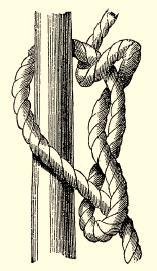

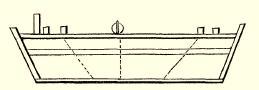

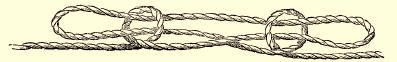

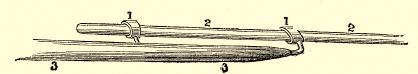

under the titles Rack, Spider-hoop, No. 2, and Topsail sheet bitts, No. 3. BELFRY. An ornamental frame fixed on the top of the pawl-bitt or elsewhere, in which the ship's bell is hung. BELL-BUOY. A kind of large can-buoy (or cone-shaped pontoon) placed in a lofty erection of wicker work containing a bell with several tongues to sound by means of the heaving of the sea. See Buoy, 4. BELLS. See Watch. BELLY OF A SAIL, when inflated by the wind or of a curved timber, is the inside of its curve. The outside of a curved piece of timber is called the back. BEND. To make fast. To fasten two ropes together. To Bend the Cable (Fr. Etalinguer), means to make it fast to the anchor ring; a chain cable is secured to the ring by means of a shackle. See Cable Bends. To Bend the Sails (Fr. Enverguer), is to extend and fasten them to their proper yards or stays. BEND. A species of knot by which a rope is made fast to any thing or one rope to another.

carrick bend. 34

|

hawser bend.

sheet bend. The key to the above sketches, and to most of the sketches of hitches given under that title, is contained in Darcy Lever's old but standard work, The Young Sea Officer's Sheet Anchor. BENDS, or WALES (Préceintes), in Shipbuilding, the thickest strakes of plank put round the outside of a vessel between the blackstrakes. See Wales. BENTICK-BOOM. See Boom (Plate IV. 68). BERMUDA SCHOONER-RIGGED BOAT, and BERMUDA SAILS. See Schooner-rigged Boat. BERTH. The place which a vessel occupies alongside of a quay or elsewhere. To berth a vessel means to fix upon and put her into the place she is to occupy. See also Hawse, 2. BERTH (Fr. Cabane) also means a small room in a vessel set apart for the use of any officer, seaman, or passenger. Their beds, or the places where hammocks are slung, are likewise called berths. To berth a ship's company means to give each man the allotted space in which to sling his hammock. To give the land (or any object) a wide berth is to keep at a due distance from it. BERTH AND SPACE. See Timber and Room. BERTHING. 'The term now-frequently, perhaps most generally, used by seamen to denote the bulwark of a merchant ship. In naval architecture, it denotes the planking outside above the sheer-strake, and is called the berthing of the quarter-deck, of the poop, or of the forecastle, as the case may be. It is also applied to 35

|

denote the close boarding between the head-rails, in which case it is called the berthing of the head; this is frequently termed by seamen the head boards.' BETWEEN-DECKS, or 'TWIXT-DECKS (Fr. Entrepont). The space between any two decks of a vessel. BEVELLED. Not square: formed with an acute or obtuse angle. The term is derived from an instrument called a bevel, by which such angles are taken. Hence, the bevelling of a timber implies the angle contained between two of its adjacent sides: if an acute angle, it is termed an under bevelling (or bevel), and if an obtuse angle, a standing bevel. We also speak of a timber having a square bevel, that is, having its adjacent sides at right angles to each other, but this is an incorrect application of the term. BIGHT. A bend in the shore forming a small bay or inlet. BIGHT OF A ROPE. Its middle part, or some fold of it between the two ends. When any such parts of a vessel's rigging, as of the braces of yards, are slack, the braces are said to hang in bights. BILANDER (Fr. Bélandre). 'A name almost indiscriminately applied to small coasters.' It formerly denoted a two-masted vessel with a peculiar form of mainsail 'bent to the whole length of a yard hanging fore and aft,' with an upward inclination of about 45 degrees:' a mode of rigging which came to be confined mostly to Dutch vessels. BILBOES. Iron shackles to secure the feet of prisoners or offenders. BILGE OF A CASK. Its middle part, which has the greatest diameter. See Chime. A cask when stowed in a ship is said to be Bilge Free, if properly set upon beds so as to prevent its bilge, which is the weakest part, from resting on anything. A ship is said to be bilged, when any part of her bottom or bilge is driven in by violence. When such an injury occurs to the upper portion of her hull, she is said to be stove. BILGE, in Shipbuilding, that part of a vessel's bottom which begins to round upwards, at the point where the floors and second futtocks unite, and whereon the ship would rest if laid aground. It is strengthened outside and inside by thick planks, termed the bilge planks, a security which along with extra bolting is the more required, as the shiftings of the timbers at this part are generally shorter than elsewhere. 36

|

BILGE COAD. See Bilge Keels and Launching Ways. BILGE KEELS, also called Bilge Pieces or Bilge Goads, are pieces of timber fayed on the bottom of a vessel edgeways, which, by their resistance to the water, serve to prevent the ship from rolling heavily, as well as from drifting to leeward. They should be wrought on parallel to the main keel, and in such - a position that when the ship is sailing close-hauled, the one on the lee-side may be nearly vertical. In iron vessels, angle iron plates are in like manner used for the same purpose. In a sharp-bottomed vessel such pieces are sometimes put upon the bilge for her to rest upon when aground, in order to prevent her taking too great a list. BILGE KEELSONS. See Keelson. BILGE PLANKS. Thick planks which run round a vessel's bilge in a fore and aft direction, both inside and outside.':(Plate II. fig. 6.) See the article Ceiling. BILGE PUMPS (Fr. Pompes d'épuisement de cale). See Pump. BILGE TREES. A name given in some places to Bilge Goads. BILGE WATER. Water which, by reason of the flatness of a vessel's bottom, lies on her floor and cannot go to the well of the pumps. Not being drawn off, it acquires an offensive smell. This is most apt to accumulate in very tight vessels. When the ship is listed over, it may be removed by means of the bilge pumps. In some vessels a pipe is inserted through the side with a cock, which gets the name of a sweetening cock, fitted to its inner end, for admitting water to mix with the bilge water. BILGE WAYS. See Launching Ways. BILL, or PEA. The extremity of the arm of an anchor, where it is tapered nearly to a point. BILL BOARDS, or ANCHOR LINING. Pieces of board or plank fixed between the projecting planks of the bow (sometimes having iron plates called Bill-board Plates nailed to them) – and likewise pieces attached to the bulwarks – to guide the bill of the anchor past these projecting planks. BILL OF HEALTII. A document obtained from the consul or other proper authority, certifying the state of health in the place she sails from and of the ship's company at the time of her departure from it. See Quarantine. 37

|