Captured at Sea By a Murderous Crew

U. S. yachtsman relates 64-hour ordeal under guns of escaped convicts

William Rhodes Hervey, Jr.

Commissioned in 1943, the U. S. Navy sub-chaser SC-1005 was decommissioned in 1946, acquired by Paul Whittier in 1950 and named Paollape. It was subequently acquired by the author in 1958, and renamed as Valinda.

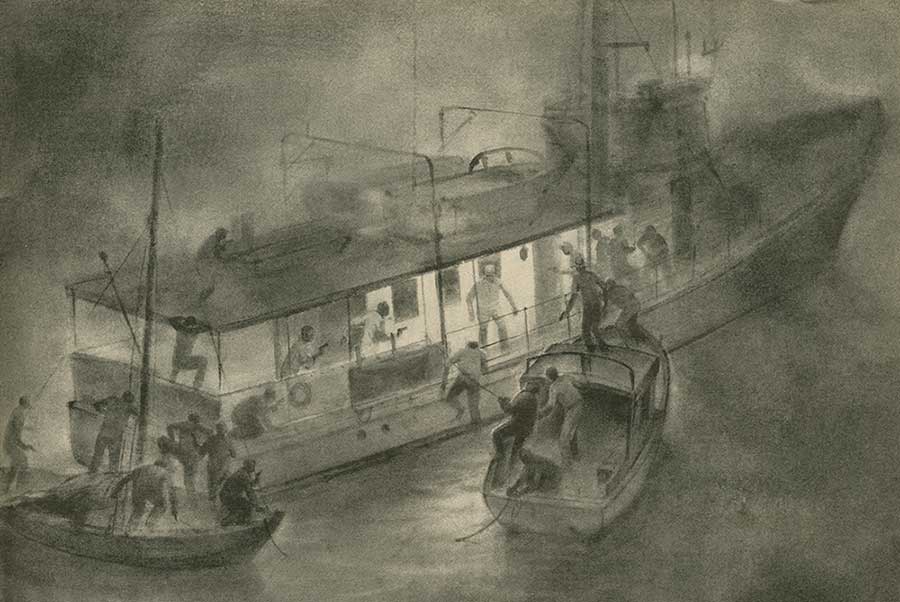

As yacht Valinda lies at anchor in darkness near penal colony, 21 armed men swarm aboard and pin owner Hervey in flashlights' glare

For the date of February 15th the log of my yacht Valinda bears a simple but terrible entry:

0300 hours captured by 21 escaping convicts who demand we take them to the Ecuadorian mainland.

The log tells nothing of the 64 nerve-racking hours that followed. This is the first chance I have had to give a detailed account of an adventure that was certainly the most memorable of my life.

On Feb. 14 we had dropped anchor in James Bay on the western shore of San Salvador Island, 20 miles from Isabela, largest of the Galápagos group. This was the halfway point in our leisurely three-month voyage about the 110-foot Valinda, a converted sub-chaser. Soon we would be starting the 2,900-mile trip back to Los Angeles.

That night my wife Mildred reminded me that there was a convict colony on Isabela. In these waters a friend in a sailboat had been chased last year by a boat full of fidagreeable-looking characters. Just as they were about to come alongside, the brereze freshened and he pulled away, but he had a real scare. With the powerful Valinda I was not worried. We could run from anything we were likely to meet and the convicts were safe on the island under guard. I thought our friend had been chased by harmless fishermen.

At 9:30 Millie retired to her stateroom below and shortly afterward my friend Wilfred (“Bos'n”) Easterbrook, our mate, went to his. The three other crew members were asleep up forward. I got into pajamas and lay down on a bunk on the open afterdeck. Except for one light high on the mast, Valinda rode at anchor in darkness.

At sea I am a light sleeper. It was 3 a.m. when I was awakened by the popping of a single-cylinder engine. I stepped to the rail and looked out. The sky was dark but I could see the outline of a boat coming alongside and the agitated waggle of flashlights. I sensed that there was still another boat astern just out of sight. Sleepily I assumed these were some fishermen we had seen earlier, returning to sell us lobsters at this ungodly hour. “No langosta!” I called out, waving them off. “No langosta!” But the boat kept edging closer. I walked slowly forward along the rail, shouting at them to keep off.Just amidships they bumped Valinda. Flashlight beams blinded me. Hands grasped the railings and as I stood there helplessly we were boarded by a pack of shouting savages. Each man carried a flashlight and above each light loomed a vicious face.

I was outraged. I reached out and flicked on the light which illuminated the passageway along the starboard side. Instantly a dark hand reached past mine and flicked it off. The snout of a revolver jabbed stiffly into my belly. In the single moment of brightness I had seen that without exception the boarders were carrying pistols, and my anger turned to fear. A group of them jammed around me in an evil-smelling circle and jabbered in Spanish. I could understand little of it but occasionally caught the word “Guayaquil.” They wanted me to take them to the Ecuadorian mainland, 650 miles away.

A bad moment

Suddenly my wife, wearing only a nightgown, appeared in the doorway of the main cabin a few feet away. She was terrified, and as the group around me parted slightly, I reached out and caught her arm. I drew her toward me and stood between her and the man. Flashlights jabbed at Millie and the men talked and laughed among themselves. It was a bad moment. I could hear men running and shouting all over the ship as they looked for the rest of the crew. Millie told me that another bunch had come swarming over the stern and had routed her out of her stateroom.

By this time Bos'n Easterbrook, Engineer William McKay and Crewmen Rick Di Maio and Balbino Ninal had joined us in the passageway. Di Maio, who once taught Spanish, talked to the boarders. He learned that our sudden guests were 21 escaped prisoners from the colony on Isabela, they they had captured the two fishing boats they used to reach us and that now they wanted a fast passage to some deserted beach on the mainland. Short of leaping over the side, which I briefly considered, we had no alternative. The men were armed, dangerous and desperate for freedom. If we refused, they would certainly kill us.

Engineer McKay asked me what they wanted. “They want to go to the mainland,” I answered. “Then what the hell are we waiting for?” McKay asked sensibly.

At 4:15 a.m. we weighed anchor and put to sea. Each of the fishing boats had carried two fishermen. The convicts left one on each and took two hostages aboard Valinda, warning the men remaining behind that any alarm or chase would result in the immediate death of their friends. We headed for the open sea and the mainland beyond. If we were lucky with our navigation and the weather and the unpredictable temper of our captors, we should make a landfall in about two and a half days.

The convicts decided it was time to eat. Taking over the galley, they began turning out great messes of rice and fried eggs. They dropped butter into the pans a pound at a time. That first day they were the most desperate eaters I have ever seen. During their short stay on board they managed to put away 60 pounds of butter and some 30 dozen eggs, not to mention cases of canned fruits and vegetables and meats. They were so starved for sugar that they filled tall glasses with it halfway to the top, poured in water or fruit juice and then ate the sticky concoction with a spoon.

As day broke we began to get our first good look at the boarders. They were a grim and ragged lot. Most had on filthy blue denim or khaki trousers and soiled white undershirts. Several wore high-topped black and white sneakers. All were unshaven and most had an Indian cast to their features. There appeared to be three or four leaders of the group. One was a young white man, barefoot and wearing a denim jacket and trousers and a sort of railroader's cloth cap. He once spoke to me in French, and indeed if you had cleaned him up and put him in a city suit, he would have looked like a Parisian gentleman. Another, wearing a leather jacket with a fur collar and a leather hat with ear flaps tied on top, hand an Oriental cast to his features and was referred to by the others as El Chino. The third leader was a heavily muscled Negro about 6 feet tall who had two bullet wounds in his left leg received during the escape from Isabela. This man looked especially trigger-taut and dangerous. He carried his pistol in his hand much of the time.

As we learned later, our captors were the most dangerous of men, all serious criminals, many of them murderers. When they got to know Rick Di Maio they told him terrible stories of tortures they had suffered on Isabela at the hands of cruel guards, of hours suspended in the air with a rope under their arms, of beatings and of starvation.

Once under way we held a conference among ourselves and clarified our course of action. We were going to take these men to the mainland as quickly as possible and get them off Valinda. That was our only chance of survival. I split our group into two four-hour watches—Millie, Rick and I in one, Bos'n, McKay and the cook in the other. We would go about our duties as if there were nothing wrong. We would not antagonize our dangerous guests in any way if we could help it. We would make no attempt to use out radios. One of us would be with Millie at all times.

Rick was told to inform the convicts that we stood ready to cooperate in their flight but that they must let us move freely about the ship, must not steal or damage our property and above all must not molest my wife. He told them this in the completely matter-of-fact tone of voice he used with them throughout the trip. I am convinced that his calm courage and that of the rest of our group is all that preserved our lives. The convicts assured Rick that while they would have to take some of our clothes when they left, they would not steal anything else and they would not bother Millie. Events proved them liars on both counts.

In the wheelhouse that first morning, I plotted our course for the mainland. We had no charts of the area between the Galápagos and the Ecuadorian coast, so I worked from a general index chart of the whole area, which is roughly comparable to plotting an exact course from San Francisco to Salt Lake City on a child's map of the world. As we worked out our navigation, these armed bandits popped in and out of the wheelhouse, wiping the food from their faces, to make sure we were up to no tricks. The terrified fishermen that had taken as hostages reassured them.

A zest for cleanliness

Noon passed but we were too distraught to think of food. From the wheelhouse windows we watched the convicts prowl the ship. They had begun to shave and even shower in the stateroom baths below. We had about 1,000 gallons of fresh water aboard and we hoped their zest for cleanliness would not exhaust our water supply.

At 2 o'clock Millie and I finished our watch and left the wheelhouse. Without looking to the left or right we walked straight through the main cabin. Sprawled in our green overstuffed chairs, smoking our cigarets and playing cards at our dining table, the convicts were making full use of the first-class accommodations. None spoke to us. We went directly down the companionway to our stateroom. There Millie changed from her night clothes into a long-sleeved blouse and a skirt. She then lay down on her bunk to rest a while before we went back to the wheelhouse. I stretched out on my bunk. The door in the companionway was open a few inches but hooked to the frame at the top.

Suddenly I heard footsteps on the stairs. Looking up, I saw our evil friend with the wounded leg, which Bos'n Easterbrook had cleaned and dressed. He stood peering in at us, weaving slightly from the motion of the ship, gesturing imperiously with his revolver for me to come to the door. I rose and walked toward him. He jabbed the pistol into my stomach and motioned for me to unhook the door. I shook my head. He drove the gun into me again and snarled a command in Spanish. I heard Millie rise out of the bunk behind me. I unhooked the latch and stood facing him. He smiled slightly and pointed the gun in the direction of the stateroom bath. He obviously wanted me to get in there out of the way. He started past me at Millie.

It is hard to explain what happened next. I remember no feeling at all. I simply moved forward slightly, forcing the man back a foot or two from the doorway. Suddenly Millie slipped through the narrow space behind me and darted up the stairs toward the main cabin. The bandit angrily reached around me and grasped her ankle. She kicked backward and broke his grip and we all dashed up the stairs, a strange trio—Millie, then me, then the angry convict. Once in the main cabin in sight of his comrades he made no further move. I took Millie to the wheelhouse.

Except for a very few occasions when she went under our protection to other parts of the ship, Millie stayed in the wheelhouse the rest of the trip. She has told me that if any of that terrible gang had approached her again, she intended to throw herself into the sea and save us all from the sure death that would have come from trying to defend her.

As evening approached we managed to eat a little soup and fruit from the stores up forward, but no one was hungry and none could think of sleep. Valinda's engines pounded smoothly on as the sun went down. That night the main cabin took on the aspect of a weird seagoing nightclub. Making the rounds of the ship, we could see the convicts playing cards in the lighted room. Occasionally one would rise from a chair and dance alone to the wild rhythm of one of our cha-cha records. Long after all but their wheelhouse guards had fallen asleep, we stepped over their sprawled bodies in the cluttered room and turned off the phonograph.

The next day, Sunday, [February 16] the looting began. Venturing below, we repeatedly caught them ransacking drawers and stores. They took money, jewelry, flat silver, clothers, everything. Occasionally they would demand a watch or some keys from one of us, and out stock defense was that one of their own band had beat them to it. But we managed to hide very little of value and they stole more than $2,000 in cash.

The plastered pirates

Sunday was also the day they began drinking. Some of the ship's liquor was out in the open in the cabin, more was in a locker, and there were several cases in a storage compartment. They got into it all and we were very much afraid that they would all get roaring drunk and forget how necessary we were to their passage. Though they managed to use up almost two cases of rum and gin, they only got jovially plastered and either fell asleep or just sat there grinning foolishly. Fortunately their leaders regarded drinking as a serious threat to their own safety, and they quietly tossed several bottles over the side. The ship became filthy with thrown food and cigarette butts and the lower decks were foul-smelling and incredibly cluttered. But the men wreaked no actual destruction on Valinda.

Our original course for Ecuador was for a beach near the town of Manta. Late Sunday the convicts decided that this was too dangerous and made us head farther north toward the lonely beaches near the town of Esmeraldas. By then we had traveled 400 miles from the Galápagos and expected to reach the coast by mid-afternoon the next day. Valinda was performing beautifully, speeding ahead through quiet seas on a soft southeasterly wind. As life insurance we made her operation look harder than it actually was. I frowned and puzzled over the sextant many more times than was necessary and Rick and McKay made repeated trips out of the hot engine room, shaking their heads and muttering to the ignorant guests “muy complicado”—terribly complicated.

At 5 o'clock Sunday afternoon the entire ship's company took part in what certainly must have been one of the strangest ceremonies ever performed at sea. One of the more intelligent convicts, a frail man now wearing my clothes, had told us earlier in the day that he and the others wanted us to come to the afterdeck at five for a presentation. Exactly what he meant by this we didn't know, but we decided we would have to do it, if only to preserve the illusion of our calm. We put the ship on automatic pilot and gathered on deck at the appointed hour. With great bravery Millie sat in a canvas-backed chair and we all stood behind her. The convict leaders rounded up their somewhat drunken company and stood in a compact group across the deck from us. There was a moment of heavy silence and then the frail man began to speak.

An exchange of Compliments

As Rick explained it, he said they all appreciated our attitude toward them. They were grateful for the food. They were sorry for the great inconvenience they had caused us in their flight for liberty. After a whispered prompting from the wounded convict, the frail man added that they were especially sorry for the fear and trouble they had caused the señora. She would be perfectly safe to leave the wheelhouse and return to her stateroom. At that, Millie calmly told Rick to give the convicts her thanks but to tell them that she preferred the wheelhouse to the stuffiness below decks.

Then Rick, speaking for me, went on to say that we were all sympathetic with the cause of liberty, that we could understand their desire to escape what they had called the living death of the island, and that we hoped they would all find the new life they sought.

Then, unbelievably, with the frail man leading them, the convicts sang a chorus of the Ecuadorian national anthem and followed it with three shouted vivas for Ecuador, three more for the United States and finally three for liberty. After this, with Rick beside me, I concluded the charade by shaking hands with each man and saying in halting Spanish that tomorrow would be the great day of liberty. Some smiled at me, others stared uncomprehendingly. I prayed that my prediction, however badly stated, would come true. We returned unmolested to the wheelhouse.

That night was peaceful enough. The convicts were preoccupied with getting ready for disembarkation. We ate a little that night and some of us were even able to doze.

Monday morning [February 17] the afterdeck was jammed with the travelers' loot—a jumble of seabags, bulging burlap sacks and matched Hervey luggage. The looting was complete, but we were still alive and Ecuador was just over the horizon.

Then, slightly off our starboard bow, we saw a ship heading north. It was a most unwelcome sight. At that point we wanted no help from the outside world. Rescue by the Ecuadorians or even a U.S. destroyer might make a nice ending for a movie, but in this situation it more likely would have meant panic among the convicts and death for us. As the convicts talked worriedly among themselves and repeatedly drew their revolvers, the single-stacked merchant vessel crawled past us about two and a half miles away and disappeard over the horizon.

The day wore on past noon and the convicts began coming into the wheelhouse to question us about our arrival time. Shouldn't we already be there? Were we up to something? Rick assured them that our more northerly course was causing a small delay but that we would have them there by night.

At 3 o'clock we made our landfall. The sight of the great Ecuadorian hills rising out of the sea was as welome to us as any land ever hailed by distressed voyagers. The convicts were beside themselves with excitement and El Chino, fully outfitted in my clothes, stumbled drunkenly into the wheelhouse and congratulated me.

Getting the men off the ship proved to be the most trying episode of the whole affair. As we approached land, they grew particular about their choice of a suitable beach and became like a bunch of Sunday picknickers looking for a better spot. As the light began to fail the breeze picked up and it became choppy. At last as we came along a curving beach with five or six primitive houses set back from the sand, I insisted they leave. They muttered but agreed. I edged Valinda close to the darkening shore and Rick and the others worked desperately to ready the big power launch for the final disembarking. The convicts lined the rail, all freshly shaved and wearing their new clothes, their luggage stacked beside them, almost like passengers leaving hte Ile de France. Some were even scented with Millie's perfume. A large crown of women and children stood on the beach watching us.

A little more that 100 yards offshore I headed the bow to the beach. At this point the launch got fouled on the boat deck and my crew could not budge her. Finally, after perhaps 15 minutes of furious effort, they swung her over the side and lowered away. Before she hit the water the convicts were throwing gear over the side and then leaping after it. Then the launch engine would not start. The battery refused to turn over. There were 12 convicts in the launch, crewed by Rick and Bos'n, and nine more still waiting to leave. We ran down a cable from the charger in our engine room and applied iti to the launch battery. The engine finally caught and roared in the night. We swung our searchlight and aimed it at the beach.

How Rick and Bos'n unloaded those men I will never fully understand, but it was a great feat of seamanship. Feeling his way through the great dark waves, Rick drove the launch practically to the edge of the breakers, swung her around bow to the sea and simply ordered the convicts to get out. Out they went, one at a time in the chest-deep water, holding their loot over their heads.

Aboard Valinda, the frail convict who had conducted the Sunday ceremony came into the wheelhouse to say goodbye. He kissed Millie's hands and embraced me convulsively and then, obriously very close to tears, he fled to the launch. The second unloading went more smoothly. But while Rick was gone I suddenly noticed that the convicts had competely overlooked their fishermen hostages in the mad rush for freedom. The hostages had overheard the band plotting to kill them when they reached the mainland and were now imploring us to get a move on. At any moment the convicts might come swarming back to recapture them. Rick and Bos'n arrived alongside and we got the launch back on board Valinda. We turned off our searchlight and moved away from the beach—slowly at first until we cleared the shoal water, then at good speed for Panama, 450 miles away.

Before we turned on our radio transmitter and broadcast the news of our escape, Millie and I hugged each other tightly there in the wheelhouse that had been our prison for almost three days.

A United Press report, 10 days after the convicts left Valinda